11 Years Later, I’m Still Mourning A Complex Death Complexly

On not getting over it, and letting a meaningful death become a part of you

On not getting over it, and letting a meaningful death become a part of you.

TW: Death, Emotional Incest

My dad died on Valentine’s Day 2007.

That’s the way I say it when I want to be considerate of other people’s feelings. The reality is, he might have died a day earlier, or two days earlier — he was incommunicado long enough for the police to go searching around his house. And they found him. My mom thinks he was splayed out in his recliner, because it was open and extended when she came, days later, to clean things out.

My dad’s body was found on Valentine’s Day. I was 18, in my first year of college. I was out on a date when the cops showed up to my mom’s condo with the news. They had my dad’s cat with them. My sister saw the cop and the cat in the doorway and knew immediately what had happened. I wouldn’t know for several more hours.

This wasn’t the first time the cops had been sent to where my dad was living. After my parent’s divorce, he had a roommate. The roommate was a younger man, in his late 20’s or so. He had a girlfriend. The girlfriend was a minor. The cops came looking for her, after she went missing.

My dad said, back then, that he knew nothing about the teenage girl, or where she’d gone. I don’t know if that’s true. He was a bad liar, but he was always lying, so we all got numb to it. Stopped caring about it. He claimed that he quit smoking when I was born. Hypnosis. 16 years later, I was cutting class and I caught him in the park, lighting up.

I kept the fact to myself, until I got in trouble for cutting class. Then I dropped the bomb. Said I was cutting class to spy on him behaving badly. It got me out of trouble. I was selfish and canny, like him.

He was always getting caught when he fucked up. He wasn’t sly. But he kept trying. I got that from him, I guess. I’ve always loved a good scam. Like him, I’ve always thought I deserved more than I had. And like I’m him, I’ve always held on to my pain, squeezed every last drop of self-pity out of it.

I didn’t have my phone with me on my Valentine’s Day Date. It was a chintzy flip phone, about two inches long, a chirpy little cricket that I didn’t need breaking the mood. I ate shitty mall French Food with my boyfriend and played a balloon-shooting game in an arcade while my phone buzzed on my dorm desk.

I remember coming home, drunk on illegally bought, sugary champagne, and finding my phone with tons of missed calls and voice mails. I don’t remember what I thought about it. I called back, robotically, I guess, and learned the news.

The champagne was already popped and my boyfriend had no clue what to do with the information, so we drank more. He knew my dad and I were estranged. So estranged I’d changed my last name. Nothing about the situation suggested there was a correct thing to say or do. So we drank, and I fell into a heap in his bunk bed, in my underwear, already getting a headache.

My sister’s birthday is February 7th. He missed it that year. But he was still alive at the time, so he didn’t have a good excuse. She called him up, furious, chewed him out, made him cry. He was always crying. He was always screwing up and crying over it but never getting better. He was the living embodiment of the fact that sensitivity is not always goodness, that knowing one is bad is not synonymous with getting better.

And my sister, a newly-minted 14-year-old, already knew better than to take his crap or feel sympathy for his tears. So the last words she ever shared with him were a righteous reaming.

I think that’s the last time any of us spoke to him.

My sister was the one who told him I had changed my last name. They were sitting in his truck. He started to sob. Head in his hands.

He had given her a note, to give to me. In the note, he asks me to listen to a song on the radio and think about him, and then call him. He says a lot more than that, in the note, but that’s the punchline. By then we hadn’t been speaking for well over a year. The note was written on a yellow legal pad in his shaky chicken scratch, one of the few giveaways of the cerebral palsy he’d hidden all his life. I don’t remember what the song was, and I sure as hell didn’t listen to it. I barely read the whole note. It went in the garbage.

He mowed lawns around our neighborhood, got paid under the table. He had always dreamed of being an entrepreneur, and that was the closest he ever got. My senior year of high school, he was hired to mow the grass around the pool where I worked as a lifeguard. I saw his red hair and his bright red truck in the distance, and I turned my back on him, or went and hid in the pool house. He didn’t come up to the fence, didn’t try to talk to me. Around town, I never saw him. He’d disappear from grocery stores or parking lots if I materialized. He knew enough to keep himself scarce. Or he couldn’t bear for me to run him off again.

I wonder still what the final cut was. Which rejection killed him.

Nobody else in my family calls it a suicide. But I’ve always been certain it was. He had diabetes, but didn’t check his blood sugar for years. He asked his doctor for more and more “cheat days”, days where he could eat whatever he wanted and feel no guilt. He smoked in secret for a decade and a half. He made himself impossible to love, hurt himself and demanded endless support and said hurtful things without relent.

He had been killing himself for a long time. And one day, he succeeded. And I was sure, so sure, that it was my fault.

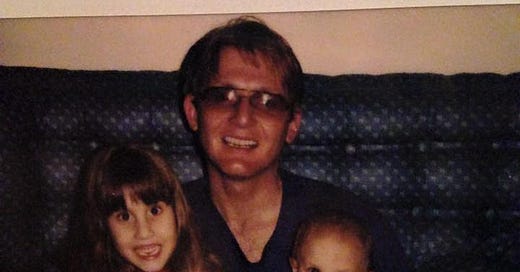

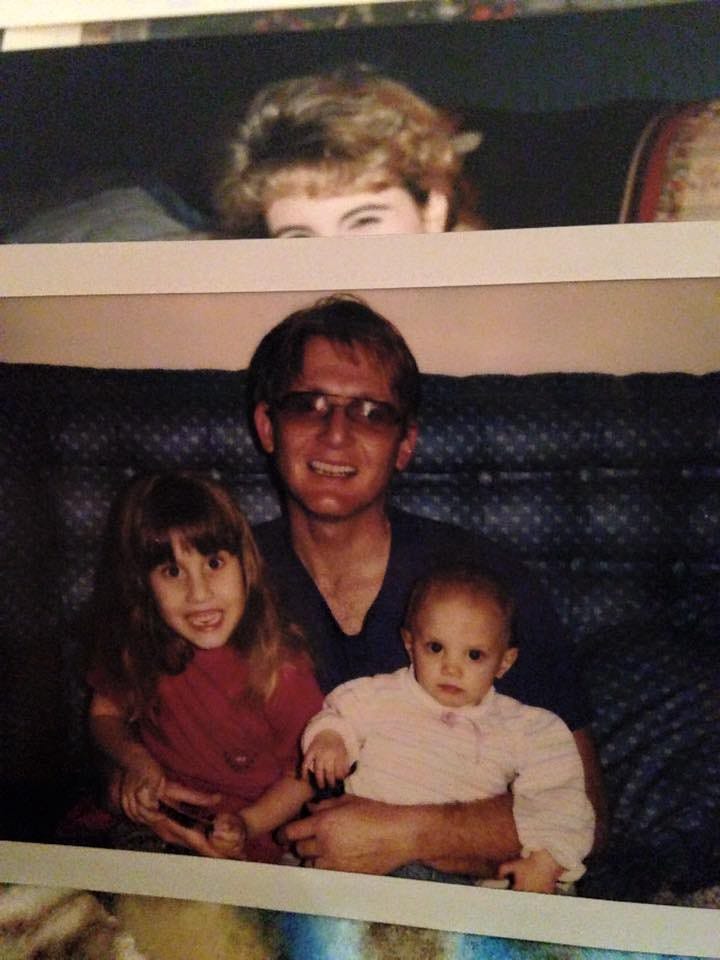

I was my dad’s therapist, emotional support animal, best friend, and child until I was 16 years old. As a kid, I apologized for his rage outbursts — told my sister he didn’t mean the terrifying, dark things that flew out of his mouth when he was disappointed in us. As I got older, and his mother died and the divorce creeped up behind him, I became the only person he could share his feelings with. I used to relish getting to hear about the adult problems that troubled him. I liked the responsibility.

But it ate away at me. I was haunted — still am — by being his spouse at 13. I looked just like my mom had looked, when she was young, and he didn’t hesitate to tell me about it. If we went to a water park or a fair and there were young girls and women there, attractive ones, he’d tell me how I stacked up against them. He said once that I was hotter than my mom had been at my age. He told me about a sex dream he had about my aunt. He let me mow lawns with him and he paid me in cash, told me I should get a separate bank account for my earnings — because my mom didn’t need to know everything. The words chilled me.

When his mom died, and again when my mom kicked him out of the house, the burden of his needs became heavier. He cried. He cried so fucking much. At movies and in cars. In the garage. That part was fine. It was his endless talking and the need for me to absorb his tears that really eroded me. He’d call and rant into the phone and I’d keep the receiver a foot away from my ear, feeling sick and over-exposed, unable to understand why.

I was the person who placated him, who listened, who was there, who understood that he couldn’t control his mouth or his eyes or his ideas. I was the one who had to call him a few times a week, and listen to him for an hour, because I’d promised him I’d do so. And then one day, I just, stopped.

And that was it. That was when I really killed him. The one time I didn’t pick up the phone.

That’s why I was disowned, can you fucking believe it? For missing one phone call.

He left me a rageful, foaming-at-the-mouth voicemail. He wasn’t gonna help me with college. He wasn’t going to be my dad anymore. He wasn’t going to love me anymore.

I was so relieved to have an excuse to cut him off. I’d been waiting for him to do something bad enough for years.

Here’s how the grieving process went. For a year or two, I was intentionally numb. I tried to never speak about him or his death. I told no one at school that it had happened. I told no one at work. I didn’t take a single day off. I cried in private only. Insanity leaked out at the edges of my day. The night after his funeral, I got hammered at my friend Katie’s house and stripped naked in front of everyone and passed out on my boyfriend’s lap. When, at a party, my boyfriend mentioned missing his years-dead uncle, I simmered with hate. Get fucking over it, I thought.

I saw death everywhere. Depending on where I was sleeping, I would wake up and check to see if my sister, or boyfriend, or dorm-mates were still breathing. I imagined my dad’s body decaying in his house. I watched documentaries about services that clean up after corpses.

I became certain that, like my dad, like everyone in his side of the family, I would die young, and suddenly, and deeply alone. That didn’t bother me exactly. Like him, I was self-destructive. It was the deaths of other people that shook me. Every happy moment was punctuated with visions of the people I loved dying. I still have this problem. I always, always will.

I became terrified of abandonment. My experiences with my dad had taught me that drawing a boundary left me alone. I recommitted to being a supportive, passive emotional pet. I listened to people and mirrored their emotions with painstaking effort. It didn’t come naturally to me, but I strived to be an active listener, a nonjudgmental dispenser of encouragement and advice.

I let people pour their worst fears, suicide ideations, traumas, and petty resentments into me. I knew if I refused to do these things, no one would love me. I had to be a good person, and I came to believe that being good was superior to feeling good.

I had killed my dad with my iciness. I really did believe that. Whenever I thought of what had happened to him, my mind echoed the words blood is on my hands blood is on my hands blood is on my hands on a ridiculous loop. I had to make up for the evil thing I’d done. By being perfect and unselfish, easy to love, responsible, giving, boundaryless.

That was how the first five years went. I tried to ignore the trauma. During that time, I wracked up a few additional traumas. I was in an abusive relationship with a volatile, demanding person who expected me to nurse his every emotional wound. I was assaulted by someone who placed his momentary desires far above my comfort. I gave myself away, emotionally, to anyone who was there. I didn’t always see how these experiences resembled my childhood.

I started feeling very far away. I got depressed. I wanted to stop existing. I smoked in secret in the park. I still felt like a murderer. When I reflected on my life, I saw myself as a villain figure, albeit a sympathetic one. I knew I wasn’t going to hurt myself in a visible or permanent way. Because that would be too much for my sister. I wasn’t living for myself.

And then, I started writing about it.

I’ve written a lot about it. Every story about my childhood, my mental illness, my worst fears, my inability to be vulnerable with other people, my compulsive saving of money, my need to justify my existence through good deeds or accomplishments, is a story about him.

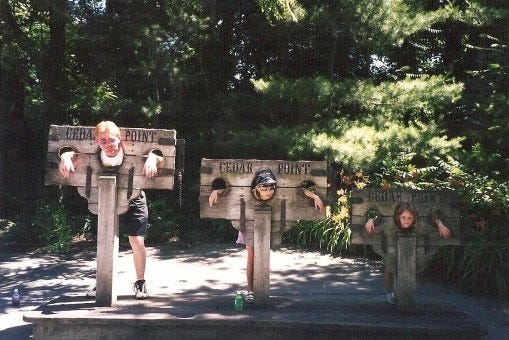

It was so much more than a death. It was years of being screamed at for saying no to something, or for ordering an ice cream that was a dollar more expensive than what he’d wanted to get me. It was an adolescence of knowing how he felt about my body, seeing how tortured he was by it, and not benefiting from his shoddy attempts at bottling those feelings up. It was a childhood of having to intuit another person’s moods and needs, distracting me from even considering contemplation of my own.

It was the guilt of killing someone by saying no to them, indirectly, once. It is the buzzing of his angry, resentful, paranoid, deprived voice in my head, and the knowledge that it’s not actually his voice I’m hearing, it’s mine. It’s the fear of being just like him, brittle and furious, a seeping open wound that cannot care for anyone or anything else.

And I will always be writing about it, because it is always there. That wound. That shitty way of thinking. That fear. It’s all jumbled up. Every bad thing in my life leads back to it. If I hurt my partner’s feelings, it’s a sign that I am abusive jackass like my dad, and that I will rot alone in an empty apartment, like he did. If I cut off a demanding friend, then I’m certain they’re going to die from my neglect, just like my dad did. If I’m having a shimmering, summery moment with my sister or a nice dog or my mom or a friend, it doesn’t matter, because one day they will die just like my dad did.

The writing helps. It’s the only thing that ever has. It lets me see how everything is so tightly connected. So maybe I’m grateful that I still have so much to say about it.

A few years ago, after writing about it a lot, his death stopped being this white-hot, turbulent thing that had happened to me. It shifted into a thing that I was. It became an integral part of my backstory. My dad died in a sudden, gruesome way and I can’t tell anybody about it became, instead, when I was 18 my dad died, and that will always be a part of who I am.

My old last name stopped being a secret. I’d mention off-handedly that Valentine’s Day was horrible for me, because that’s when my dad’s body was found. Sometimes I’d overshare and make people uncomfortable. It was a sign of progress. It used to be so rare that I’d tell anybody a thing about myself or my feelings. It was probably annoying or perplexing to others. But it set some of my demons free.

The story of my dad’s death has gotten so much more complicated as I have processed it more deeply. He wasn’t a monster. He was a deeply sick person. He had a disability he was forced to hide for his entire life. He had to make up excuses for the things he couldn’t do. The shame he must have felt, my god. He saw a little girl die, bloodily, when he was just a child himself. It gave him seizures. Those had to be hidden too.

He had to work jobs that didn’t satisfy him, manual labor jobs that didn’t require the dexterity he didn’t have. He couldn’t type or write. He was smart, but he was never allowed to use those smarts. He worked in a warehouse loading cakes onto trucks for years; he’d have nightmares that the cakes would never stop coming, that he would be trapped moving them forever. He had no friends. He self-harmed by eating sugary food and smoking. The one person who treated him with emotional intimacy was a tiny, odd little person that was 50% him. And all of a sudden that tiny person was big, and hated him.

My role in his death has gotten more complicated in my mind, too. I started teaching teenagers, and I saw how fresh-faced they were, how vulnerable. I couldn’t imagine myself unloading a trough of emotional shit onto any of them. I came to realize how little self-knowledge and self-love I’d had, back then. I got to thinking that maybe saying “no” to him wasn’t such a terrible thing. I thought about how much worse my life would have been, if I’d kept feeding him the endless support he craved. I thought maybe his death was inevitable.

At some point, the story became one of a wounded, ill man and an imperfect, brash teenager. His death became an explanation for all my triggers and flaws and compulsions, and for my growth and compassion as well. I’d run so far away from him that I’d actually developed some of the self-love and emotional competence he’d always lacked. I became the hero of my story, and his death was my origin. It was where I got my powers and my weaknesses. And sometimes, I kinda loved who I was. So I was thankful to have gotten there.

It’s been a long time. I can go weeks without glancing at a single memory of him. Then I’ll get a piece of mail for an Erika Bohannon, or some words will slip out of my mouth in a mock version of his Tennessee hillbilly accent, or I’ll see a redhead somewhere with aviator-style glasses and wonder if he didn’t really die. I’ll think about him and start craving some nicotine, consumed in secret. I’ll get dizzy and get to wondering if I have diabetes.

Then I’ll wave it from my mind, and it’ll dissipate, but it doesn’t float away. It gets reabsorbed. This is who I am. It’s an integral part of my identity. I don’t have to think about it much anymore, but it’s there. It’s an adversary I will always return to, and duel with, every Valentine’s Day and Father’s Day and every time I drive past the park in Ohio where he used to secretly smoke. And each encounter will improve me.

If you’ve lost someone recently, or years ago, and if that death was complicated, I want you to know that it will always be a part of you. You will always feel it. And it’s better if you don’t aspire to get over it. It has changed you. There are things you know that you didn’t know before that death happened. Things in you have been fundamentally reshaped. And that is wonderful, actually. It’s a superpower. You’re never gonna get over it. You’re always gonna be thinking about it. But that’s a good thing.