Autism is a Creative Boon.

A list and exploration of 5 openly Autistic actors, musicians, and artists.

A list and celebration of 5 openly Autistic actors, musicians, and artists.

I’ve written before about the public — and professional — misconception of Autism as monolithic. Since it was first “discovered” by neurotypical professionals, Autism has been seen as a severe condition that appears in withdrawn, difficult boys who adore math, cars, or lining up their toy trains on the carpet. For decades this stereotype has persisted, and reinforced itself; Autistic people who match the stereotype are more likely to be diagnosed and receive services, and Autistic people who are women, or Black, or who are creative and expressive are ignored and discounted.

The persistent portrayal of Autism as monolithic is a direct result of doctors and psychologists’ disdain for Autistic people. If you want to eradicate Autism from the population — an end-goal desired by many doctors & therapists, as well as all of Autism Speaks — it’s to your benefit to paint the Autism with wide brushstrokes. A homogenized, over-simplified view of Autistic people makes it easier to view them as less-than-human. Conversely, if you acknowledge that Autistic people vary in all kinds of ways — and acknowledge that many of them benefit from their Autism — the view that Autism ought to be “cured” (read: purged from society) gets a lot harder to justify.

The fact is, Autism is an incredibly diverse and multifaceted neurotype, a source of human variation as beautiful and complex as eye color or body shape. Autism is not a simple spectrum for “low” to “high” functioning; it’s more like a sundae layered with a variety of toppings. And each one of those “toppings” — Autistic traits — can be mild, moderate, or strong in its intensity.

Sometimes, Autism comes with a heavy sprinkling of sensory sensitivity. Sometimes, it comes with a delicious caramel drizzle of disliking eye contact. Autism can be topped with a bright red cherry of hyper-focus. Or it can be filled with chocolate chips self-stimulatory behavior. Each Autistic person has a unique combination of Autistic traits, each in different amounts.

And, just as ice cream toppings combine in interesting ways with the base flavor of the ice cream itself, Autistic traits interact (and intersect) with the Autistic person’s other attributes — such as their gender, race, culture of origin, and personality. Autistic women are often more skilled at making eye contact and feigning neurotypical behavior than autistic men are, for example. Similarly, Autistic people who are creatively inclined may develop an obsessive special interest in music, painting, or sculpture, rather than the more stereotypical trains and math.

Autism is diverse, in part, because it isn’t some malignant disorder that impairs functioning or erodes personality. It’s a neurotype — a core part of who a person is. And all kinds of people can be Autistic. To illustrate this, I’d like to introduce you to five famous, creative Autistic people.

This List is Carefully Curated

There are many bad lists of “Celebrities with Autism” on the internet. Often they’re rife with speculation, and impose a diagnosis on a person from afar, without their consent. The lists tend to include historical figures who wouldn’t have even been familiar with Autism during their lifetimes (like Emily Dickenson or Albert Einstein), and celebrities who have done reprehensible things (like Woody Allen).

I’m not interested in placing a label on anyone who hasn’t already actively claimed it. I’m also not interested in celebrating Autistic (or suspected-Autistic) people who are predatory or who view their Autism as a negative. Therefore, this list only includes celebrities who have publicly self-identified as Autistic (or as having Asperger’s), and who have discussed their Autism as something that society should work to accept and accommodate, rather than eradicate.

These openly Autistic people are all creative, expressive people — and that’s a very deliberate choice as well. These individuals flout the stereotype of Autism as condition that blunts and flattens; their lives and work reveal Autism to be a source of vibrance and uniqueness. Their struggles and challenges point to the fact that Autism is a neurotype that must be better accommodated and understood by the neurotypical public, rather than destroyed/”cured”.

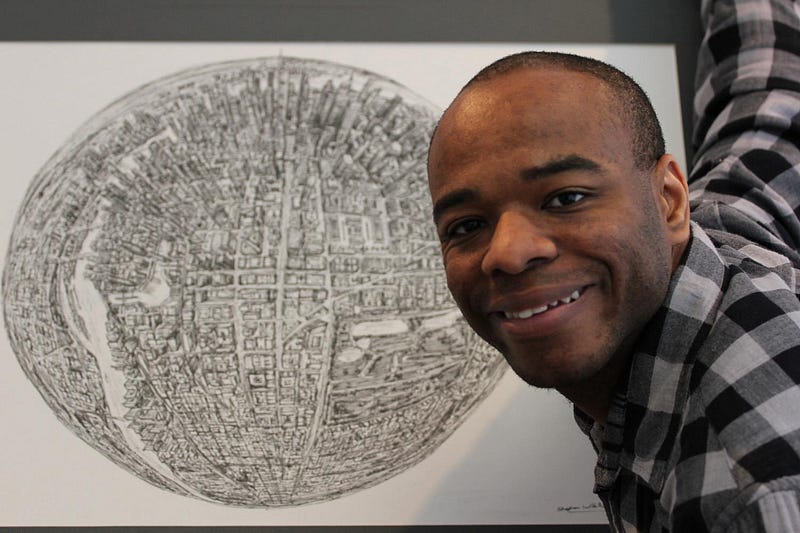

Daryl Hannah

Actor Daryl Hannah has described, in numerous interviews, the impact being Autistic has had on her professional life as an actor and activist. Throughout her life, she has been underestimated, and excluded, due to neuroatypical behavior such as avoiding eye contact and rocking in place to self-soothe. When she was a child, medical professionals mistakenly believed her disability warranted institutionalization and heavy medication. She was not expected to live an independent life. She defied this underestimation by moving to LA to pursue acting.

Throughout her acting career, Daryl Hannah embodied characters that were intense, fiercely independent, and charismatic in their strangeness. Her roles in Clan of the Cave Bear and Splash, in particular, strike me as Autistic-adjacent. In both films, her characters are outsiders thrown into societies — and species — that are utterly unfamiliar, with strange customs that are hard to obey and social norms that are difficult to make sense of. The characters weren’t intentionally written to be Autistic, of course, but Hannah’s portrayal of them is infused with her own neuroatypicality.

Hannah’s character in Kill Bill can also be easily read as an Autistic. Elle Driver is a strange spitfire, utterly unique in her style of dress, mannerisms, and way of speaking. Throughout the entire movie, she paves her own odd way — breaking rules, dressing like a weird 1970’s business pirate, and refusing to tolerate ignorance or disrespect. Though she’s aligned with the titular “Bill”, she follows an ethical system all her own — and tramples over anyone who gets in the way of it. Autistic people often loathe following pointless social rules — including gender norms and standards of politesse. Elle Driver illustrates that beautifully, in a captivating, severe package.

Though Hannah was unquestionably a talented and distinctive actor, her career suffered due to other people’s intolerance of her Autism. Hannah found movie premiers and awards shows intensely anxiety provoking, and avoided giving interviews as much as possible. She was discouraged from publicly using self-stimulatory behavior (or “stimming”) — a practice many Autistic people find calming and immensely beneficial — as a means of processing her anxiety. Eventually, multiple film studios blacklisted Hannah in response to her social awkwardness.

Daryl Hannah’s experiences are an excellent introduction to the social model of disability. Hannah was clearly capable of being a proficient, talented actor. Her major impediment, professionally, was other people’s expectations of what acceptable professional behavior looked like. Today, she is an effective and devoted environmental activist, and does occasionally still appear in films and TV. Her latest role, as of this writing, was Angelica Turing in Sens8.

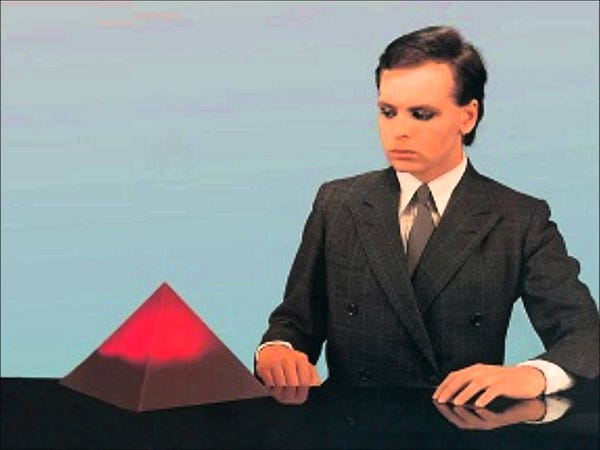

Dan Aykroyd

Autistic people are often stereotyped as being monotonous and humorless. Actor and comedian Dan Aykroyd’s is a perfect counter-example. In fact, he has frequently cited his Autism as a font of creativity, and the main reason that Ghostbusters even exists.

Aykroyd exhibited early precursors to Autism as a child — including Tourette’s — but did not seek an Autism assessment until adulthood, at his wife’s prompting. One of his most evident Autistic traits was his special interests — he was obsessed with ghosts, ghost hunting, and law enforcement throughout the 1980’s, which lead, in part, to the creation of Ghostbusters.

Aykroyd also credits his Autism with the development of many of his characters. As a child, he spent a lot of time looking at his own image in the mirror, making faces and practicing expressions. Many Autistic people struggle to emote in socially appropriate ways, and use facial or verbal ticks as a stim; Aykroyd used these traits to hone his performance skills. In an interview with the Guardian, he states:

“My very mild Asperger’s has helped me creatively. I sometimes hear a voice and think: “That could be a character I could do.”

Though a state of Autistic hyper-focus is often mistaken as a flat, robotic state by neurotypical people, Aykroyd’s work demonstrates that it can be a source of inspiration and expressiveness. In addition, Aykroyd’s affable, warm public persona challenges the notion of Autistic people as cold and unemotional. Aykroyd shows clearly, and proudly, that Autistic people can be goofy, friendly, and expressive. They can love music, comedy, vodka, and ghosts, just like anyone else.

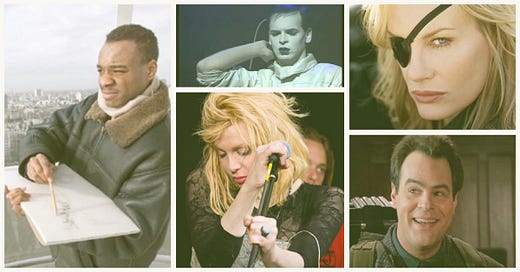

Stephen Wiltshire

Architectural artist and “human camera” Stephen Wiltshire is perhaps best known for the viral video in which he recreates a cityscape with photorealistic detail, after viewing it just once from the window of a helicopter. The video, and much of the writing about Stephen, unfortunately buys into common journalist tropes about Autistic adults: he’s portrayed as an “inspiring” savant, whose worth as a disabled person has been earned via his talent. Even his moniker — the human camera — reinforces the stereotype of Autistic people as robotic and inhuman.

But Wiltshire is so much more than all that. A London native, Wiltshire was nonverbal throughout his childhood. Like many Autistic people, he found forming words difficult, despite immense social and educational pressure to communicate in neurotypical ways. His special interest, and primary mode of communication, was always drawing.

Teachers forced a five-year-old Wiltshire to speak by withholding arts supplies from him. Frustrated, and denied his central mode of self-expression, Wiltshire produced vocalizations, and eventually said his first word — “paper”. He became fully verbal several years later.

Initially interested in drawing animals and cars, at age seven Wiltshire became interested in the city’s landmark buildings. A teacher accompanied him on drawing trips throughout London, and Wiltshire began to develop his skills and receive local acclaim for his hyper-realistic sketches. His photographic memory, Autistic hyper-focus, and obsessive interest in architecture allowed him to make creative and technical strides with remarkable speed. Local acclaim exploded into national and international notoriety, and at age 8, Wiltshire was commissioned by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to draw the Salisbury Cathedral.

Wiltshire and his art have toured internationally, and he has published four books of his work. His third book, Floating Cities, made it to the number-one position on the Sunday Times Bestseller List. In 2006, Wiltshire opened a permanent art gallery in London’s Royal Opera Arcade. He has drawn cityscapes from memory throughout the world, and often uses his art to fund raise for locations that have been devastated by natural disaster.

Wiltshire is an Autistic figure of incredible importance. His story highlights that Autistic people can be deeply creative and expressive, that nonverbal people have massive and beautiful inner lives, and that neurotypical social skills are not required to live a life of fulfillment and success. Wiltshire’s childhood mistreatment by teachers also should serve as a reminder that Autistic people deserve to pursue their passions, and that they shouldn’t be denied their creative outlets as a means of forcing “normal” communicative behavior on them.

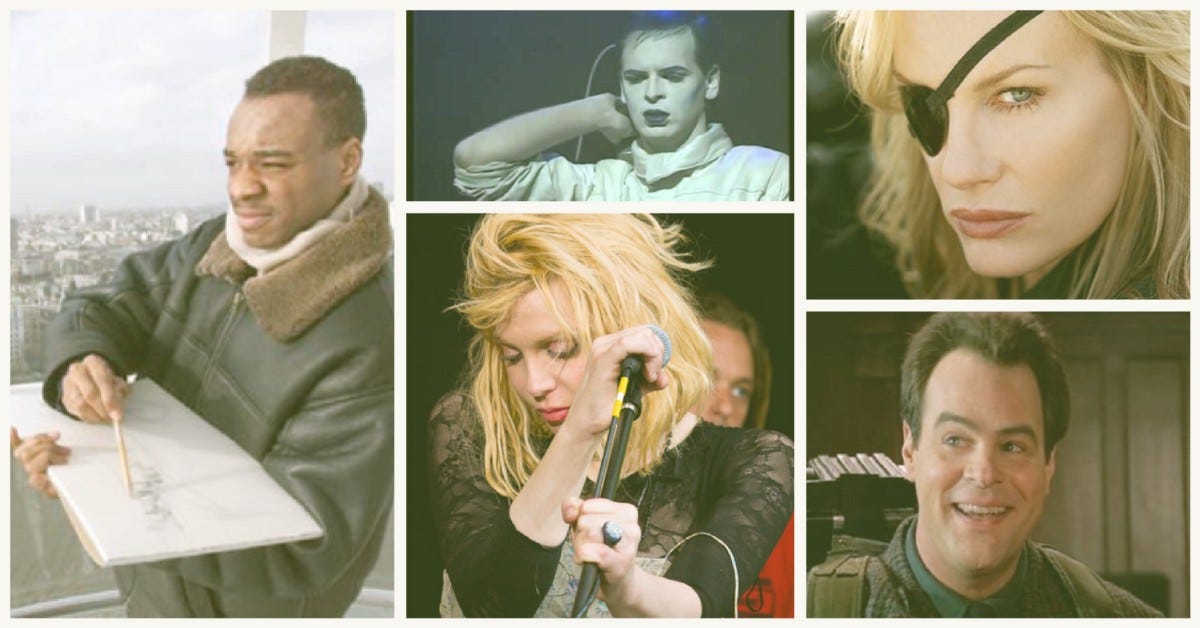

Gary Numan

In 1979, British musician Gary Numan introduced the world to paradigm shifting, genre-breaking synthetic music with his albums Replica and The Pleasure Principle. In the years since the release of those albums, Numan has remained a ridiculously prolific, experimental, and genre-busting artist, all traits he attributes to his Autism.

Numan experienced Autistic meltdowns and behavioral problems throughout his childhood and adolescent years; symptoms for which he was medicated. As a teen, he developed special interests in piloting and, when his father bought him a guitar, music. He rapidly developed into an immensely productive artist: by age 21 he had released three albums, in two different genres.

Following the release of his second and third albums in 1979, Numan soared to notoriety. He found the sudden spate of attention and media appearances very anxiety-provoking and overstimulating. To make performances bearable, he established an alienlike, robotic stage persona, with stiff movements and a faraway stare. This persona entranced his early fans, and allowed Numan to incorporate his Autism into his performance.

Numan continued to churn out albums throughout the early and mid-80’s, and made frequent media appearances, though he was infamously shy and awkward. In interviews, he’d avoid eye contact and hide behind hats and heavy makeup, and would sometimes fidget with toy planes. His responses to interview questions were often hyper-literal and unexpectedly candid — which often threw interviewers for a loop.

Numan maintained his high productivity throughout the 90’s and 2000’s, creating music in a variety of genres including punk rock, synth pop, and industrial music. In interviews, Numan frequently explains how his neurotype helped him to thrive and grow as an artist — Autism allows him to focus intently on the music he is creating, allowing the rest of the world to “drop away”. His varied special interests have driven him to pursue mastery of multiple genres.

Throughout his early career, Numan’s parents provided him with a great deal of support — his father served as his manager, and his mother made his costumes and ran his fan club. As an adult, his main source of emotional and social support is his wife, Gemma O’Neill. Gemma has an Autistic brother, and was the first person to suggest that Numan look into the neurotype as an explanation for his tendency towards obsession and his social problems. Numan’s career illustrates that Autistic people can be successful professionals and artists, even if they struggle with social skills or executive functioning. When Autistic people have an encouraging and understanding support network, they can thrive in fields that are unfairly tailored to neurotypical people.

Courtney Love

Musician and actor Courtney Love was identified as Autistic by a therapist when she was nine. As a child, she struggled behaviorally and academically, and had trouble making friends. As a teenager, her behavioral problems worsened, and she was expelled from school, then arrested for shoplifting and sent to a juvenile correctional facility. She became legally emancipated at sixteen, and began working odd jobs and stripping to support herself.

In college, Love still struggled to make friends, and developed social skills by emulating drag queens that she had watched at local gay bars. Many Autistic people identify strongly with fictional personas, and adopt the language, mannerism, or personalities of media figures they admire — and in Love’s case, it proved successful. She began acting and performing music, using the outlandish, wild persona she had developed for herself. She eventually taught herself to play guitar, and in 1988, formed the band Hole.

Courtney Love’s early music was a testament to her experiences as a disabled and socially alienated young woman. Hole’s debut single, “R*tard Girl” describes a mocked, alienated disabled girl; in interviews, Love has stated the song is about her experience of getting picked on for being shy and awkward as a child.

Courtney Love transitioned from music to acting in the mid-1990’s, and in 1996 earned a Golden Globe for her performance in The People vs. Larry Flynt. Throughout the 2000’s, she continued acting, producing music as a solo artist and with Hole, and even dabbled in visual art and fashion.

In interviews, Love is infamous for being unfiltered. Her frank discussion of drug addiction, grief, and legal troubles made her the subject of a great deal of media interest over the years. Her openness, strangeness, and candor have often been interpreted as signs that she is still actively using drugs, or that she is an irresponsible parent and a “mess”.

Viewing Courtney Love’s creative success, adventurousness, and strangeness through a lens of Autism helps a unified image of her come into focus. She has been less direct than some of the other people on this list about how her Autism connects to her professional life, but the content of her lyrics and her choices of acting roles reveals a common thread: like every other Autistic person mentioned here, she found a creative outlet that allowed her to express deeply-felt estrangement from mainstream, neurotypical society.