A guide by a nonbinary psychologist.

Researchers: This is your regularly-scheduled reminder that if you are measuring gender in a survey, your options should not be “Male” “Female” and “Transgender”.

As a psychologist, survey designer, and statistical consultant, I encounter a lot of bad gender measures in surveys, and have to work with a lot of the bad data sets that result from them. A lot of scientists are making a lot of poorly-thought-out decisions regarding the role of gender in their studies, leading to data that either excludes transgender people entirely, masks their presence in the study, or forces them to pick a nonsensical option that the research won’t know what to analytically do with.

But all these pitfalls can be avoided. All you have to do is be a bit more intentional about your use of gender in your studies. Consider the following factors:

Why are you measuring gender in your study?

First, ask yourself what you are really trying to measure with a gender item. Are you looking at how gender identity is related to some outcome? Are you interested in gender presentation — how a person dresses or is read by society? Are you interested in a person’s biology? Do you care about how they were raised? Are you not sure which of these things you care about? Make sure you have a precise idea of what your variables are.

Gender is a multifaceted variable, involving societal roles, standards of presentation, expected communication styles, feelings of kinship with fellow gender-group-members, preferred style of dress and grooming, biology, hormone levels, childhood socialization, and so much more. And, even among cisgender (i.e., non-transgender) people, not all of these things line up.

For example, a cisgender woman might have been raised to follow “female” norms of dress and presentation, but she might not have a uterus because of surgery or a medical condition. A cisgender man might have received “male socialization” but might communicate in a way that is more feminine-seeming. A butch cis woman might identify as 100% female but might be perceived as a man by people around her, because of the way she dresses or carries herself.

Gender is complicated, including for cis people — so when you’re measuring gender in a study, precision is key. For example, if you are doing a study where a participant’s gender identity matters, ask about their identity, not their sex. If you are interested in something biological, ask whether participants have the anatomy/hormones/etc you are actually interested in. If you are studying how gender norms affect a person, it may be worthwhile to ask them about how they were raised, and how people perceive them, gender-wise.

Be direct and clear. Collect the data you need.

Do you need to measure gender at all?

While writing a survey, you should also ask yourself if you need to measure gender at all.

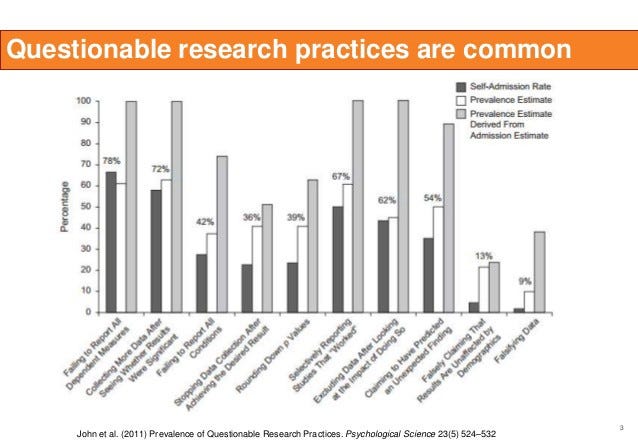

We survey researchers tend to throw in demographic measures thoughtlessly, and analyze them in a pretty sloppy way. Gender, race, socio-economic status, education level…these “obvious” measures are almost always thrown into a survey as an afterthought, even if we have no hypotheses pertaining to them. Often, we re-use the same demographic items over and over again, never taking a moment to consider if our racial category options are limiting or inaccurate, if our SES measure is useful, or if our gender response options are a good fit.

Once we get this demographic data, messy though it may be, we often feel compelled to use it. So we throw them into analyses to test out their potential impact, or to see if using them as control variables helps uncover effects we cannot otherwise identify. This “throw spaghetti at the wall and see if any of it stick” approach to data analysis increases the odds of false positives. At best, it leaves us with results we weren’t planning to look for, and for which we cannot explain. It’s useless and sloppy. It’s a questionable research practice.

Scientists can avoid all of this by thinking intentionally, during the study design period, about demographics. Ask yourself if you need to record data on race, SES, and gender. Consider why you need this data, and how you’re gonna use it. If gender is not related to any of your hypotheses, and it’s not needed as a control, don’t measure it.

How do you measure male or female identity?

Now, let’s say you’ve determined that A) you have a good reason to measure gender, and B) you are interested in gender identity, not a person’s biological sex/what a person was assigned at birth. And let’s further say C) you want to be inclusive of trans people.

I hope C is a given. If you’re doing research on men and women, especially psychological research, you should care about the psychology of trans men and trans women just as much as cis men and women.

(Unfortunately, it’s often not a given that researchers want to include trans people in their studies. Some researchers forget we exist. Others imagine we are such a small or strange group that we can’t bring much of value to their studies. But, awareness of, and interest in trans people has increased over time. So let’s assume you’re a good researcher who wants to get representative data and measure gender well.)

Now, you can choose to label your binary gender options a couple of different ways: Male and Female, Woman and Man…

I think Woman and Man is the better set of options because it doesn’t imply biology the way words like “male” and “female” sometimes do.

Either way, you should make sure the survey question asks about gender identity if what you are concerned about is identity— “What is your gender?” or “What is your gender identity?” are both simple and comprehensible to most people. Don’t ask about sex/biology unless you care about it specifically.

And if you’re doing psychological/educational/consumer/etc research…you probably don’t care about biological sex. If you’re not studying your participants genitals, reproductive organs, chromosomes, or adolescent development, you probably don’t need to know their sex. Their gender is almost certainly the thing you care about.

Nonbinary and Trans-Inclusive Options (And How Not to Fail at Them)

So you’ve decided that measuring gender is a worthwhile thing for you to do, and you have written a survey question that makes it clear gender is what you are interested in. And, since you’re a diligent and well-informed researcher, you want to make sure your gender options are inclusive of trans people and nonbinary people (people who are not men or women). What do you do?

This is where a lot of well-intentioned but ill-informed survey writers screw up in a fundamental way. A lot of researchers list “Transgender” as their third gender option.

This makes no sense. “Transgender” is not a gender. All that a “transgender” label tells you is that a person’s gender assignment at birth does not match their identity.

And if you care about a person’s gender identity…you should just ask about that identity.

A trans man is a man. His gender identity is male. A trans woman is a woman. Her gender is female. If you handed a trans man and a trans woman Psychology Today’s awful gender item, neither would pick “transgender” as their gender.

This is a flawed analogy, but suppose you asked participants, “What is your religious affiliation?” and your options were:

A. Protestant

B. Catholic

C. Muslim

D. Jewish

E. I converted to my religion

Listing “I converted to my religion” as a religious identity option is like listing “Transgender” as a gender option. In this context, “Transgender” is an answer to a question that hasn’t been asked.

It’s bad survey design. It makes no sense to respondents, or for analysis purposes. It makes it impossible for you to compare men and women in a manner that includes trans folks, and to compare cis folks from trans folks. When someone selects “male”, using the measure, you have no way of knowing if they are transgender or cisgender, and if someone selects the “transgender” option, you have no way of telling if they are a trans woman, trans man, or nonbinary person. it’s a mess.

So what do you do instead of listing “transgender” as a gender option?

Well. Let’s ask again: What are you trying to accomplish?

Are you trying to include nonbinary people?

Then add nonbinary options to the list. Things like:

Nonbinary

Genderqueer

Genderfluid

Some gender not listed here: ______

Notice that the last option in that list allows people to self-identify, but doesn’t label them as an “other” that has been overlooked. “I wish to self-identify: _____” is also a good way to phrase it.

You should also consider making your gender measure a checklist, rather than a single-choice radio button. Many trans people have complicated identities, and more than one label may apply. For example, I am nonbinary, but I also definitely feel closer to being a man than a woman. So, when I get the chance to select multiple options, I often pick both nonbinary and male. Other trans people have identities that fluctuate, or that are multifaceted — when we are able to check off multiple options, we can honor every part of who we are.

How do you ask about trans status?

In some studies, whether a person is trans or cis may be a relevant variable. You might need to compare trans and cis people as a whole, you may need to identify how trans women’s experience differ from cis women’s, for example. If this is the case, you need to measure both gender identity and trans status.

I strongly recommend you do so using separate questions. That allows you to have clean, easy-to-analyze data on both gender and on trans status, without conflating the two. It also allows you to affirm that trans women are women and trans men are men, rather than implying that either group is some lesser/false version of their identity.

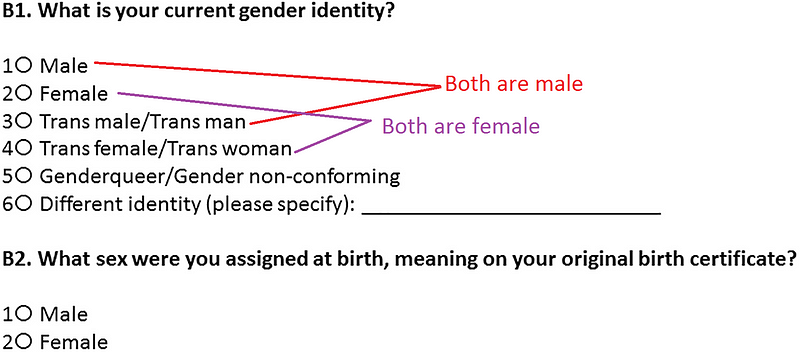

To that end, I recommend a two-question sequence like the following:

What is your gender identity?

[List of sensible options]Are you transgender or nonbinary?

[Yes or No]

Or something like that.

This example by Sarai Rosenberg is excellent:

Sarai’s gender measure is fantastic. Male, female, and nonbinary identities are included and accurately named, respondents have the option of avoiding the question entirely, and people with identities that are not listed can self-identify easily, without being labeled as an “other”. Trans status is also measured as a separate variable, so it does not invalidate gender identity. People who wish not to self-disclose their trans status can opt out of the question. (Sarai also recommends explaining to your participants why you are asking about their trans status).

If I encountered Sarai’s measure in a survey or a client’s dataset, I’d be overjoyed. If a colleague was looking for an example of a useful, trans-inclusive measure of gender and trans status, I’d happily point them Sarai’s way. However, I still think there is a tiny bit of room for improvement.

Here is a gender measure I’d consider pretty close to ideal:

As I mentioned above, I prefer a checklist format to a single-choice list of options, which this item provides. I also think it is useful to include a variety of nonbinary gender options, because we’re really quite a diverse group. Some people identify as having no gender (agender people), some people have a gender that fluctuates between multiple categories (genderfluid), and so on. Some people prefer the label genderqueer, instead of nonbinary. This measure anticipates some of the most-common nonbinary options, so people don’t have to type them in.

Notice, also, that this measure prioritizes nonbinary options. They are listed before the binary options of “male” and “female”, which is something I never see on mainstream survey measures. This helps make us look like less of an afterthought. As in Sarai’s measure, the open-ended option is not labeled as an “other”, so it doesn’t single out people with an alternate identity as strange. Male and female options are listed, but “transgender” isn’t, which affirms trans women and men. There is an option to not respond to the question at all, which is helpful to questioning and closeted people.

In Sum:

“Transgender” is not, itself, a gender. It’s a descriptor of a person’s relationship to their gender, specifically the fact that their identity doesn’t match up with the identity foisted on them by society.

If you’re doing research that requires measuring gender, or inquiring into trans topics, you NEED TO KNOW THAT. Gender terminology can be confusing at times, but this is such basic information that no one doing academic research on the subject has any excuse to not get it.

Furthermore, if you are doing psychological research, it is vital that you attain a basic understanding of what being trans means, and that you design your instruments in a way that is trans inclusive. Transgender people exist. We have always existed. But most research, even research that is explicitly focused on gender, ignores us. We cannot be understood, seen as legitimate, or served by science if we are not recognized accurately. When we are not given forms and measures that allow us to accurately self-identify, we cannot participate in science, nor can we benefit from it.

Researchers, please share your #badgendermeasures with me via Twitter or in the comments on this post. Poor measurement of gender is a widespread problem and it has a lot of ripple effects. I’ve been writing about this, and speaking to colleagues about it for years, and nonetheless I keep encountering shoddily written survey items. We can do better. The first step is widespread awareness that this is a problem.