I had been avoiding mirrors for awhile. The man on the other side was a perfectly adequate human being, but he always looked dour, and so boring. I hated smiling as him. Tiredness always clouded his eyes. It made me kind of sad to see him, but I could get away with not thinking about it.

I didn’t obsess over his appearance the way I had as a girl. I could let a flyaway hair or a cyst on his back just be for days. But I never delighted in seeing him either. When I looked away, and had no confirmation of what he looked like, he became featureless in my mind, and unappealing.

In public, my arms and neck felt stiff all the time. I couldn’t walk down the street with ease, or lose myself in my music. I was so conscious of the space that he occupied, hypervigilant against intruding against anyone, and yet insulted when crowds treated me like I was invisible and bumbled into me. My shoulders kissed my ears and my hands and feet felt like solid concrete, too hard to move.

I stopped taking selfies. Even if a new outfit excited me, I didn’t really like how it looked on him. There was a disjoint between the person that he was and the one my mind recalled us being. It was always a let down, like revisiting an old neighborhood and finding a favorite gay bar, glittering and rough-edged, had become a Sweetgreen. My wardrobe became populated with bland navy blues, vaguely brownish flannels, and loose slacks, all of which were nothing but utilitarian means to an end. Wearing these things, I felt like a thumb, five and a half feet of generic guy.

Sexually and romantically, I wasn’t sure of how to sell myself. I couldn’t imagine what people found appealing about him. As a woman the calculation was straightforward. I knew what men liked about me then, and they didn’t hesitate to tell me. I hated the fixation on my breasts and on eating me out, how slick and outward-curving and exposed I always was. When an old Dom had me masturbate while begging him to let me cum in a Valley Girl’s voice, I lost all words, then cried and cried.

But I understood the expectations even when I chose to thwart them, wiping my makeup off for the last time, lowering my voice, and jamming my face full of metal.

As a man, what I was aspiring for never came into focus, and neither did what I was rejecting. I circled the saunas and cruising rooms, taking in all the thick muscles and fuzzy, round bellies, and I saw that men were appreciated whether they were young or old, grizzled or manicured. It should have liberated me, I thought, as it did so many others. I was supposed to be finding my people. But I found that being an adrift observer was the only thing that was familiar.

I felt like the young woman in the viral photo at Folsom Street Fair from a few years ago. But on the outside I looked like any other aging twink. I was as welcome and wanted in male spaces as anyone. But I found that I actually wanted my outsides to match how out-of-place I always did feel, in every gendered space, and might feel for the rest of my life.

I had been focusing far too much on fitting in.

On the apps I heard from other trans people, chasers, nice guys with trans exes, down -low guys from the suburbs, and all the rest, but I could never pin down what they liked about me, other than the idea of the hole between my legs and its contrast with my sinewy muscles and square jaw. Hey handsome, they’d say, or I see you as a man completely, and it made me disgusted. What did any of that even mean? Why did they feel the need to make it about my gender all the time?

I didn’t emote. I didn’t approach people. I took care not to even glance in the direction of a woman or a child on the bus. Or a straight man. Or a gay one. I didn’t want anybody to feel preyed upon. Didn’t want my attention to linger. It seemed that manhood was a task of performing disinterest and detachment nearly all of the time.

I didn’t want to be too flouncy and sensitive, lest I ruin the illusion that I was a man. At the same time, I feared that my gruff, withdrawn seriousness also made me terrifying. After a few hits of poppers and several drinks at the club, I sighed and told my friend Gally I finally feel like nobody thinks I’m a serial killer! But the fear returned once my high faded and I started occupying my head again.

When I traveled to the blood bank, I pretended I was a straight, cisgender man. They wouldn’t have accepted my donation otherwise. It was a role I’d perfected a while back: I simply had to make myself more depressed, less verbally and emotionally responsive, permanently bored and sloppily dressed. You learn to play this role when you start going to the men’s restroom; the more tired and unsocial that you look, the less likely it is any other guy will give you a problem.

It worked; the phlebotomist didn’t ask a single question about my sexual habits and didn’t bother to pre-screen me for any disease. When an assistant pierced the needle through my arm at an awkward angle that dug against the side of my vein, I breathed hard and didn’t tell her that I was in pain. She grabbed the skin around my elbow and milked me for blood while Vanilla Sky played soundlessly on the clinic televisions.

I got a packet of Oreos and a miniature water bottle after. I couldn’t be happy at the little treat. That is not what Straight Devon would possibly do. I couldn’t wriggle in my seat with relief, or pride at having braved a tough situation and done a good deed. I was a man now and that meant feeling nothing, connecting with nobody, giving nothing up.

If a cisgender guy told me he felt all these things, I’d think to myself that he was overdue for a gender awakening of some kind, and might benefit from transition. But I am a transgender guy who has already run away from an ill-fitting gender at least once in the past, with a few detransitionary bumps along the way. And so my current dysphoria has me contemplating the person that I used to be, the route that’s taken me to the man I am now, and how I might put all these pieces of my life into a satisfactory whole.

…

I really hated being a woman. The incredibly complex, winking social rules of girlishness were impossible for me to keep up with; the cultural obsession with my curves and the assumption that they existed for becoming a mother and feeding an infant made me go to war with my body. I perseverated over my self-image in destructive ways, spent hours bent over the sink picking at pores and lightening my hair. I raised my voice to make it seem more feminine until doing so gave me laryngitis. I practiced swaying my hips and then fumed at the men who noticed.

In contrast to all that, becoming a man felt pretty wonderful for a while. I welcomed the stubble on my upper lip and cut off all my t-shirts to display the deltoids I tended to with daily workouts. As my breasts shrank and my shoulders widened, I liked how my clothing fit better and better, and that public attention now slid off me like rain on a duck’s back. The first few times I got sirred or himmed by a stranger were a rush.

After a lifetime of other people projecting assumptions onto me based on a body that I had not chosen, finally I was in control enough to choose something else. Becoming a man, I thought, was the closest thing to being truly seen as gender neutral, since men were the social default. Intellectually I knew that manhood came with its own set of punishing restrictions and damaging hang-ups, but I hadn’t felt them yet. I was too focused on getting free.

Getting top surgery last year took me to a new stratosphere of self-contentment. I’d needed romantic validation like it was air my entire adult life, and had done plenty of downright impulsive, expensive, and stupid things to get men to say they loved me. The adoration of others was the only buffer that could protect me from a constant drone of self-loathing in my head. But the second my chest was flat, I actually felt complete.

My sexuality settled inside itself. Fuck pursuing other people and trying to convince them to please me; I pleased me, and if no one ever came into my life that could meet all my oversized and highly particular needs, I figured that would be okay. I got me better than anybody ever could, and I was lovely. I had friends, a supportive community, a fulfilling creative life, and a body I could move around in. That was more than enough.

It was a dramatic reorientation. I could attend to my body’s sensations and needs like never before. I got so hungry. I ate so much. I spread out in chairs, letting my arms drape wide behind me. I stomped across the floors of my home with elatement.

But a great many thing still felt wrong in my body, and that wrongness was most acute when I opened the front door and allowed the outside world to intrude.

I found I could never relax and simply be myself when I was in large groups. So I stayed home. I felt a tightness in my right hip that hours of sitting for writing and meetings had given me. So I closed the laptop and took a walk. There was a deadness between my legs whenever someone else tried to touch me. So I stopped pretending to find anyone hot.

I looked around the bars, studying people, and asked myself what I even wanted. Did I want to look like the average guy in these spaces, bigger than me, more muscled, with faded hair and a jutted jaw? I really didn’t. I slipped seamlessly among the men now, but it didn’t really feel like some kind of euphoric arrival. It felt like an erasure of something unformed and weird about me that I’d never known how to appreciate until it was gone.

I’d been cutting my hair like these super-square guys for ages, because it really helped me pass. The second my hair was shaggy or covered in a beanie, I used to get she’d. For the longest time, I had to select clothing based on how it concealed my bound breasts and round thighs, drab baggy outfits protecting me but never letting me feel expressive or sexy. I lifted weights every day, desperate to keep my shape a recognizable V. I didn’t dance with my hands up, lest people see my tiny wrists. I couldn’t hug my coat close to me for comfort because I was afraid it looked too immature, in contrast to my grown-man form.

In every space I felt both a pressure to make myself less intimidating, and to obscure my femininity, both strength and softness threatening me in different ways. There were only a couple kinds of men it was acceptable to be, and I wasn’t any of them.

In videos from this time I look perpetually tired, and I was — though testosterone gave me a surfeit of energy for running errands, lifting weights, rearranging furniture, and partying, I lacked the liveliness to beam with excitement, smile warmly at strangers, bounce on my feet, or flounce with my hands. I couldn’t sit still with a book or a daydream the way I always had as a cloudy-headed, overly sensitive girl. I felt incredibly anxious and repressed, locked into a present that I didn’t like, and a body that was better, but not exactly right, and onto which others still read the wrong meanings.

I had escaped the dysphoria of being a woman so totally that now I could recognize there was also a dysphoria to being a man. I was suffering from something my friend Jess White had once named bilateral dysphoria, the confusing push-and-pull of being some kind of nonbinary gender in a world with mostly-binary embodiment and presentation options, and almost exclusively binary social scripts.

Womanhood had been so intolerable it had seemed to push me right out of the category by its own power. But now I was hitting the wall of oppressive masculinity on the other side. I was terrified of being “wrong,” of having screwed up and made all trans people look bad by having detransitioned, and I knew I didn’t want to aspire to cis womanhood again. But I had no idea where I wanted to go. And so I didn’t do anything about it for quite some time. I kept taking my T and buzzing my hair and gritting my teeth and never talking photographs or looking in the mirror.

…

Zaia is a nonbinary trans femme who also experiences dysphoria from both ends of the binary. A dancer with long, ornate nails and a lengthy braid, they’d been feminine since they were young. They’d also been beaten and sexually harassed for their gender-nonconformity throughout their life, and had never succeeded at closeting themselves as someone more masculine.

For a few years in their twenties, Zaia contemplated whether they would make “more sense” in the world as a woman. But nothing could change that certain elements of womanhood didn’t feel right.

“I take hormones, but I never wanted to develop breasts, and so now I wear a sports bra or a binder to minimize them most of the time, and you know, I really would like to get a radical reduction,” they say. “I never got laser. I never did any vocal training, not that a woman has to do that, but. I like my beard and my baritone.”

I shared with Zaia that while I also adored my body hair, I’d never personally wanted a beard. “Some features just feel different, when they are new and growing out of you,” they reflected. “For people like us, the first puberty was usually hell. And the second one can still be very awkward. Our endocrine systems can take us in one of two directions, we don’t get to pick and choose which effects we do and do not get. We can do that with surgeries! But the color palate doesn’t match the power of our imaginations. ”

Zaia and I agreed that we both found the “nonbinary” label maddeningly vague. It only defines us by what we are not. In reality there are easily thousands of nonbinary identities, some attached meaningfully to the categories of woman or man in some way, others existing in a completely different plane of existence.

I asked Zaia what their nonbinary identity meant to them. They made a clawing gesture in the air. “I’m like a mermaid. They’re beautiful and bewitching, but they have teeth that will drag you down into an abyss where you won’t know what is up and what is down and all your old assumptions will be turned on its head.”

I told Zaia that I most often thought of myself as an imp, a short, adorable, and unkept little creature that was ageless and mischievous and had a feylike amorality to them. It was hard to reconcile this self-image with society’s conceptions of either womanhood or manhood.

The imp was cute and small, which people in this dimension associate with femininity, gentleness, and weakness, and yet it was also rough and wild and uncontained, which seemed somewhat masculine, but only in a boyish, undeveloped way.

It’s not that I needed to be small, I clarified, but I liked that my short stature left me in control of my invisibility, able to blink in and out of an overwhelming reality and the sting of being seen whenever I needed. And I wasn’t afraid of aging, but the primary models of androgyny that society offered were all either inhuman or young, and Autistic people like me were never taken seriously as adults anyway. And so I kept reaching for the idea of the genderless, shy, playful, eternal imp.

As I explained all this, I kept apologizing, because it felt so stupid to regurgitate gender and body stereotypes. I wanted to break free of gender, but there was no way to reject the norms without reifying what they were. This, too, is a nonbinary experience that my friend Jess White has written about — they have compared constructing a new nonbinary identity from the fragments of the binary to building a model tree out of wood.

“If I had to point to any experience that defines being nonbinary,” they write, “it would be trying and failing to find the right words.” No matter how carefully you try to capture nature’s majesty, even using its own materials, something is inevitably destroyed in the translation.

Tree Made Out of Wood

If I had to point to any experience that defines being nonbinary, it would be trying and failing to find the right…medium.com

Zaia nodded along to all of this enthusiastically. “This is why people like us live in the depths of the ocean and dark woods and galaxies. It’s the metaphor that gets us over and above the human. Though humans did make it all up.”

We can’t ever fully escape the meanings that society has written onto us. Gay people reject feminine and masculine relationship roles— then turn around and act as if bottoms are hyperpassive incompetents who can’t drive or kill insects. Trans people protest that a person’s body does not reflect their essential qualities, and then we assume a taller, fatter person is more dominant than a petite one. We keep trying to build a new world from the scraps of our old jails, but the pieces fit together best as a cell.

Even the symbolic imp that I reach for is a combination of existing cultural images that are centuries old: the bountiful cherub, the trickster fairy, the outcast living in the swamp. The second I name myself as any of these things, I refract my self-image into them, splitting and scattering the truth.

The more I set out to be understood, the more I damn myself to oversimplification. No wonder it’s the nonsense labels and inhuman categories that feel the most accurate. They’re the least likely to be taken too seriously, including by me.

I told Zaia that one nonbinary friend of mine feels most closely aligned with aliens. Another speaks of themselves in the plural, as a chorus of angels. They found this delightful. “Everyone should build their own escape from all this, whatever it might be.”

“I am getting ready to undergo a penile-preserving, limited-depth vaginoplasty soon,” they said. “Really what I want is something like tentacles. But until modern science can do something like that, having a penis and a vagina that can only be touched but cannot be fucked is the best combination for me.”

I told them that I wished I could get horns and elf ears. Then I thought about it a little longer, and remembered a blog I followed in the early 2000’s, written by a man who’d had his genitalia almost completely removed. It was a joyous blog, filled with animated cartoons of his neutered self striding around and shaking his butt. He professed to be a very sensual man who had a fulfilling sexual relationship with his wife. He’d just never enjoyed having genitals at all, and the surgery at last made him feel like himself.

The blogger provided simple drawings of his anatomy: something like that of a Ken doll, but with a hole for urinating. As a teenager I had envied it. His body’s sheer refusal relaxed and enchanted me. I wanted it for myself. But then I’d put the idea away. Of course I wasn’t allowed to be as strange as him. I had to try and be something normal as best I could.

…

While I was deep in the throes of my bilateral dysphoria last December, I stumbled upon an episode of the podcast The Corn Corner, in which trans masculine porn creator Cam Damage discusses his fraught feelings surrounding his voice.

Cam says that on a recent call to his bank, he started off by speaking in a low register, with his voice reverberating from his chest. He was pleased when this elicited a “Mister” from the customer service representative on the other line. But as their conversation went on and Cam became more friendly and expressive, the representative subconsciously switched to calling him “Miss.” Because having enthusiasm and being kind to customer service workers is a stereotypically feminine trait, and those of us who exhibit it tend to do so with a raised pitch.

Cam’s frustration that niceness was equated with being female reminded me of some early advice I’d encountered on a popular online guide for trans men. The guide recommended wearing oversized V-neck shirts with stripes that distracted from the contours of the chest. Its author cautioned guys against wearing button-up shirts with loud patterns or bright colors.

“No matter how much you like it, don’t wear it,” he wrote. “People will only think you’re a lesbian.” On forums, transmasculine readers reminded one another to glower at strangers and take up a ton of space, and to resist the urge to smile or be helpful during parties. These qualities would only make you appear womanly.

I looked down at my depressing navy button-up and rubbed my lifeless, buzzed hair and felt just about ready to snap. I wanted to be nice to strangers, damn it! I wanted to grin, and agree diplomatically that the weather was nice even if that meant I got she’d! And who cares if I dressed like a lesbian? Some of the dearest people in my life have always been lesbians. Being mistaken for one of them was a great compliment.

The outrage at my own gendered hang-ups had reached a breaking point. I wanted to be a good listener who helped pick up all the trash and remembered people’s birthdays! I wanted to lift people’s spirits, and make them feel at ease! I wanted to be cute and sensitive and off-putting and me! I didn’t want to be a woman or a mother, but I did feel downright maternal around people who needed my care or some affection, and I was tired of holding it back.

I didn’t know what goddamn gender I wanted to be, but it was not one that is mean on the phone.

I went to Midwest Furfest that weekend, where I donned a latex catsuit and a custom deer mask with tiny antlers, giant, bouncing ears, and almond-shaped cutouts for my eyes. In the mirror I recognized myself: I was creepy and beautiful, shiny and strange, the tight rubber against my skin conducting every minute change of temperature in the air and transferring it all over my skin. I was one with my environment, and brilliantly anonymous.

I pranced about the conference halls in my black boots, shining my eyes at people, and stopping to take photos with anyone who asked me. I waved at people without shyness and grinded up against an adorably chubby fox in a Femboy Hooters crop-top on the dancefloor. I stayed out until closing that night, and every night of the convention. I couldn’t stop dashing around, flapping my hands, chugging down water and feeling it spill down the front of my suit, cooling me, and laughing and singing along to the music.

I didn’t want to take the rubber off and face my masculine human self again. In the rubber I was everything that I most feared and liked about myself all at once: creepy and odd but also adorable, small and stick-armed but also filled with an infectious passion. I was a strange thing, not a woman or a man. When a friend sent me photos of myself in the outfit, I made one of them my phone’s wallpaper for months. Never before had I loved myself enough to do that.

…

Some time after these revelations, I finally allowed myself to grow my hair out, ditch the self-consciously masculine wardrobe, and reduce my dosage of T. It took a while to get comfortable letting go of control over what my body would do. Gripping firmly to a masculine identity had been my salvation from dysphoria for so long. Now I have no idea where I’ll wind up.

But of course, to hold an identity beyond the binary is to be some amount of unknowable. The reaching for the words and failing to find them is the freedom of it.

Detransition is Gender Liberation, Too

Today, a piece came out in USA Today about my detransition and retransition, so I wanted to take a moment to speak about it in my own words. I was never really certain about my transition in the way that most gatekeeping hormone prescribers and curious members of the public demand that a trans person be. I didn’t “always know” that I was not cisgender. …

At a time when access to transition-related care is under such vicious attack, it is vital for trans people who have experienced self-doubt, revised their transition goals, or even regretted their transitions to speak out, in defense of every person’s right to explore, or even to make a mistake.

A “binary” gender transition taught me that I experience dysphoria when pretending to be either a cisgender woman or a man. The true source of my torment is not simply my body, over which I have some degree of control — it is society’s imposition of meanings and categories onto me that makes me hate moving through public life or being seen. Being forced to be either a man or a woman is the violent, psychologically damaging, dysphoric experience for me.

Dysphoria like that has no easy solution — but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a genuine problem worthy of intervention. I have the right to try and build my escape, even if it means cobbling together the pieces of the old into something never quite new enough.

A detransitioned friend told me recently, “I had to become a man for a while so that I could choose being a woman.” I feel that way now about being nonbinary. I needed the option to change my body so I could find the parts I did like about it. It is the freedom to leave that separates a cage from a home.

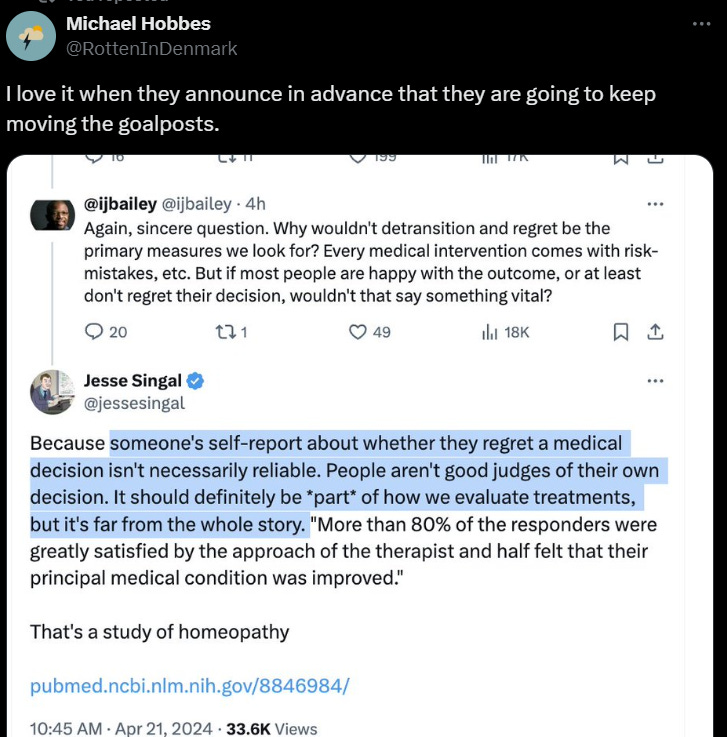

Contrary to the arguments of transphobes like Jesse Signal, I do not think that the main benefits of transition are ones an outside observer can quantify. For some trans people, hormones and surgery do dramatically reduce depression, anxiety, and suicide ideation, it’s true. But I know that if my own transition had been studied by the empiricists, they would have observed no positive change, because I never would have admitted to suffering from such things.

I don’t trust psychiatric authorities with my brain’s soft underbelly. I am too “mad” for all that. I know that admitting to my true feelings could get me institutionalized, robbed of bodily freedom, denied control over my own finances, blocked from leaving the country, and more. And so I do not give that information up, and transition using only informed consent and DIY HRT. The psychological benefits of my transition therefore exist in a shadowy realm that is unknowable to the medical system.

No medical board will ever get to surveil and pass judgement over my “outcomes.” My mental state, identity, professional standing, and sexuality will remain a confusing mystery, which will help keep them free to change, and to forever be just mine. I will never have to prove to the gatekeepers like Hilary Cass that my transition has made me a more productive or well-adjusted citizen in order to justify it. I hereby grant myself the right to remain unhappy and dysfunctional forever, and to do what I like with my body regardless.

I am thankful that no matter what happens, I will always have a transexual, nonbinary body. My chest will always lack breast tissue and milk ducts, the snaking curves of my scars and my absence of nipples broadcasting that something very intentionally strange happened here. I will always have hormonally-thickened vocal chords that can bellow with aggression and pitch upward into a friendly customer service voice. My hair will always grow in darker than the blonde it once was, blanketing me and keeping me animal and wild.

My ears have learned to perk up at he/him and it/its pronouns, but they also favor the gay she. My wardrobe will forever be a pile of cast-offs from the people I’ve previously been. There will always be a bit of copper shoved up past my cervix, preventing me from being a “mother,” so that I can save my maternal love for somebody else.

I will never not be a gender freak. I never was anything but. It doesn’t matter exactly what I do with my body now, only that I retain the power to transform it, interpret it, and re-interpret it however I wish. Every single person is deserving of that power, be they trans, detransitioned, nonbinary, or cis.

With my own weird little life, I will never win the war against cissexism. But the point is to keep fighting, to keep changing and moving, to never settle into a category that might make me easier to parse but less myself.

I'm coming from a different direction and it's such a mindfuck. "Man" is a description for me that is so utterly *wrong*. And yet woman isn't quite entirely what is fitting either. Something in close proximity to it, influenced by it, yet not wholly like it and containing inscrutable differences. Which is in no part due to society's ever-present influence: always too autistic, too tainted by a first puberty, too fucked up by a lifetime of trauma and bullshit, too outside the skinny-abled-affluent demographic; always wrong, and often a threat. Medical interventions helped with some of it, they can take my HRT out of my cold dead hands, but for other aspects it possible yet out of reach (financially for one), but for most it's plain impossible.

I'm left wondering: how much does being autistic feature in all this?

Am I too autistic to understand the binary male-female dichotomy and the very much affluent white cishet notions that people hold about it?

Am I too autistic to be seen and treated as a fully fledged human instead of Wrong and Alien?

Am I too autistic to not see the kaleidoscopic mess of traits, behaviors, etc. as anything but (self-)contradictory bullshit that people make up on the fly and having ever-moving goalposts?

No wonder I get why people find themselves in being totally Other, Monstrous, and/or Alien. Make your home for yourself out of the things that resonate. I just wish there was a map to follow, as contradictory as that sounds for some as paradoxical and personal as this, because I am *lost*. Until then I'll just refer to my gender as "none woman with left autism". If you get it, you get it, and luckily some people do.

"I hereby grant myself the right to remain unhappy and dysfunctional forever, and to do what I like with my body regardless." ❤️❤️❤️