Chicago Portrait no. 36: Asbestos and Bloody Wings

Damen Hall was fourteen stories tall, nothing but a flat unyielding tower of brick and small square Soviet-esque windows, its insides…

Damen Hall was fourteen stories tall, nothing but a flat unyielding tower of brick and small square Soviet-esque windows, its insides filled with asbestos, rats, low-hanging ceiling tiles, and old radiators that constantly spewed hot steam and made the paint and posters warp. In the winter the building got so overheated that the two sets of reinforced metal doors had to be pinned back with garbage cans so a few meager gusts of cold air from the lake could wisp their way inside. You could see a cloud of steam from the heat eking out through the doors as far as five hundred feet away. It looked like the old building was floating on a low-hanging cloud.

It was built in the era of student anti-war protests, and therefore made to be impenetrable. It stood at an odd angle, dark orange bricks garish against the perfect green turf and the pale grey blue of the lake. Everything inside was yellowing and cracked. Books were constantly being discovered in closets and closed-off hallways, their brittle pages bearing publication dates in the 1970’s or ‘60’s or ‘50’s. Most of it was utter garbage, odd tomes on Neo-Freudian theory or authoritarianism that bore no resemblance to the psychology we now practiced. Old questionnaires and measurement instruments spilled out of rusty grey filing cabinets; their loose dingy sheets inquired about nervous conditions, sexual frigidity, transvestism, and other outmoded conceptions of mental illness that we’d long learned to disregard, or at least we’d been told to.

There were old rickety elevators that broke every other day, but I never used them. Sometimes their doors would open halfway between floors, revealing the grey guts of the building. It reminded me of the boy I knew who was split in half trying to crawl through an elevator shaft. His name was Andrew Polokowski and dozens of people got sprayed in the face with his blood.

I did not risk Damen Hall’s antiquated elevator. I took the escalators instead. They zig-zagged their way from the first floor to the fourteenth, and occupied a huge bank of the building, probably comprising about 20% of the building’s whole floor plan. I’ve never seen an office building with an vast, upward snaking tower of escalators ever before or since. It was narrow and hot and the handholds were worn. It got incredibly packed and moved sluggishly whenever the bell rang and all the students came out. We all knew it to be a fire hazard but we didn’t say anything.

Once a dead body washed ashore and settled on the rocks abutting the library. It was pale and nude, shimmering in its cool whiteness, like a fish that had been cleaned in an ice bath. I’ve since learned that finding bodies nude is quite normal; the water and the rocks have their way with the fabrics and wear it all down until it frays and falls off. But at the time it presented a mystery. Who dives in nude? Someone who, in death, wishes to return to the state of birth? Who pitches a naked body under the tow of the fake tide? Who slides the jeans and socks off, a final disrespect?

Campus security came and cordoned off part of campus. We all knew that something was wrong when we saw the ambulances and slow-moving, bored firefighters. It gave us a sense of perfunctory dread. We knew that something horrible must have happened, but also that it could not be helped. Routes were changed. Coffee was bought somewhere other than the library’s lakefront cafe. Life went on everywhere except in the fish-bellied corpse’s heart.

Nobody saw the body except for a few library employees, and all the professors whose offices were in the top floors of Damen. Their tiny rooms had tiny windows that gazed across the water. In the winter you could press your nose to the glass and watch the floes of ice shift slowly and become suddenly entranced. There was no great cracking sound, just the howl of the wind, and the gentle slosh-slosh of the white planks of ice as they jostled each other from atop their bed of liquid.

With such a view being customary, spotting the body must have been hard. My PhD advisor didn’t recognize the corpse for what it was until he spotted the EMTs kneeling over the dark blue body bag.

“There’s a body!” he came out screaming into the hallway. All the graduate students looked up. “There’s a body, and it’s dead!”

I didn’t get to see it. I was in class, in a storage room that happened to have a long table in it. It was at the very apex of the building. The windows let me gaze distractedly at the pale greenery planted on the newer building’s roofs. I liked to watch the cars park and pull out on the top level of the adjacent garage. Sometimes my professor would drone on and on and the heat from the overworked radiators would blanket me and I’d watch the drivers, hoping for a small accident or altercation.

The professor was seventy years old, with a thick grey mop of Ringo Star hair. In his picture on the university website, he has the same bowl of lush hair, but it’s chestnut brown, and his face bears significantly fewer lines. His photograph and bio had not been changed for decades and neither had his lectures. The jokes made his lips fray into a wry, twitching smile; the references to literature and politics were unwieldy for most. I got a few of them, but most were too obscure.

That high up, there were many pigeon and dove nests. They slept on the roof or tucked into corners on the penultimate floor, and rose mid-day during my class to swoop down and feast on worms and students’ discarded French fries. I didn’t mind watching the birds as they cast down and returned with mouths of filth to feed their babies. It was a soothing passive distraction from my professor’s 3pm ramblings about Kurt Lewin and deinstitutionalization under President Reagan.

What bothered me was the hawks. They were alert, and truly distracting, and they lived on nests atop Damen, too. All day long they would dart and swoop, claiming the round bodies of pigeons and doves with their clawed talons.

There was no way for the little plump birds to avoid it. They fluttered and squawked and made lumbering attempts at evasive maneuvers, but the hawks were smarter and more elegant. From out of nowhere they dropped faster than gravity, stealing their prey’s bodies from their wings. It happened in an instant and a flurry of feathers.

You can find the disembodied, bloodied wings all over town, but especially near tall perches. The hawks like to live up high, so they can survey everything with the assurance of safety. Their eyes are keen and the pigeons are easy, slow-moving targets. Pulling their torsos from their appendages seems to be easy. I saw it happen dozens of times, through the window just over my professor’s shoulder.

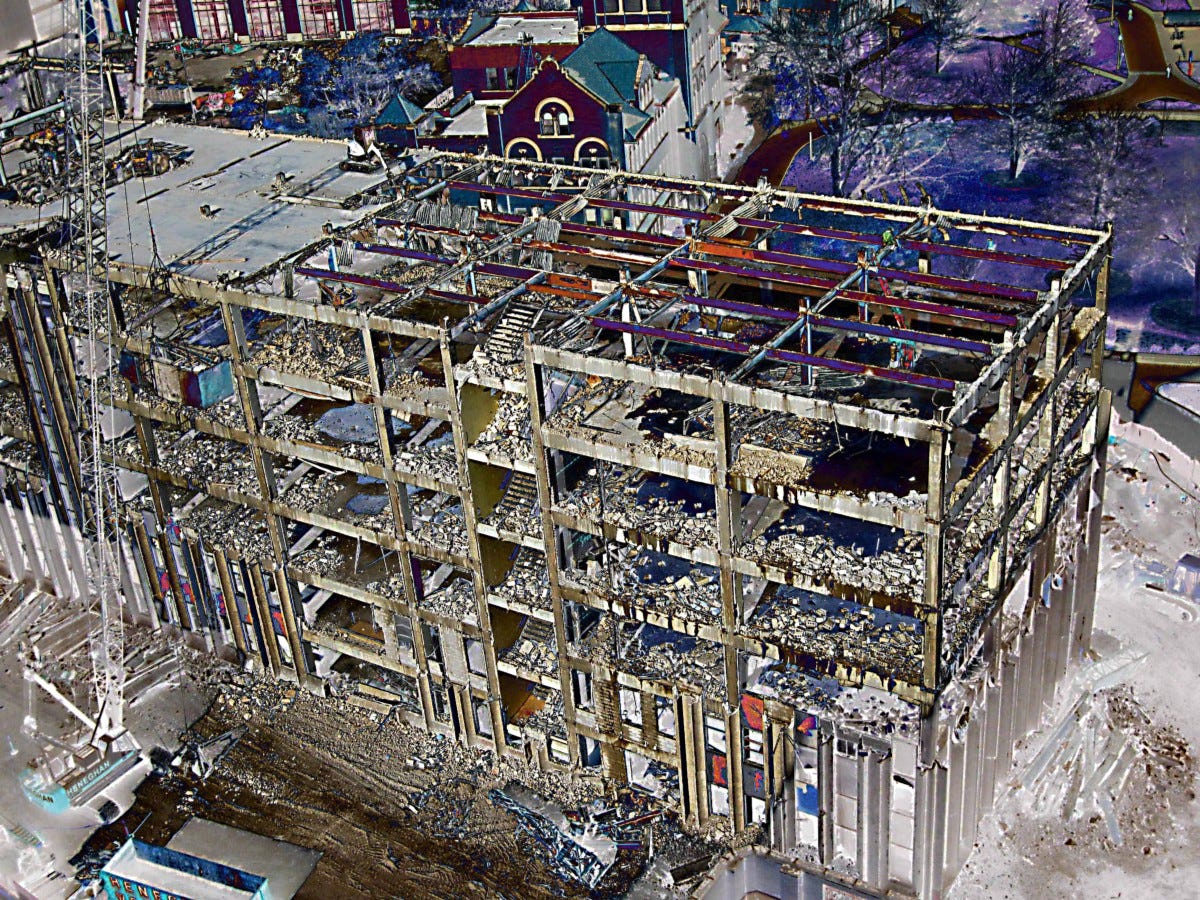

The building was destroyed nearly five years ago. Machinery gutted the insides of furniture and asbestos; I used to sit on the steps of Coffey Hall and watch the small bulldozers push the detritus out, watch it fall into the dumpster below and crash against what came before it. Then there came the wrecking balls. I loved how lazily they swung, how much damage they could just with inertia and weight. The round wrecking ball reminded me more of the pigeons than the hawks. It was firm and fat and steadfast, and wanted only to exist in space and follow the laws of physics.

Damen was replaced with a state-of-the-art green facility. Every classroom has a smart board and an array of clean, lightweight desks and chairs and a cute little podium on wheels that do not squeak. I’ve taught many students in that new building. I’ve nearly forgotten all of the dingy, embarrassing things that happened in the building that once occupied its space.

But every now and then I look up, dozens of yards above the roof of the sad little four-story, and examine the air where Damen’s upper floors used to sit. All the dust and poison and lead-based paint and blood and shit are gone from this negative space. All the books and furniture and old condom wrappers and flyers and broken staplers have been transported somewhere else. There is nowhere to stand or read, no escalators to ride on, no floor to hold a body’s weight, no windows to watch the water from, no dark abandoned laboratory for students to knock teeth and mash tongues in with the lights off.

The nests and wildlife have also fled to somewhere more hospitable. I don’t miss the bloodied wings but I do kind of miss the hawks.