Dispatches from the Northwestern University Liberated Zone

Day 1 of calling for divestment.

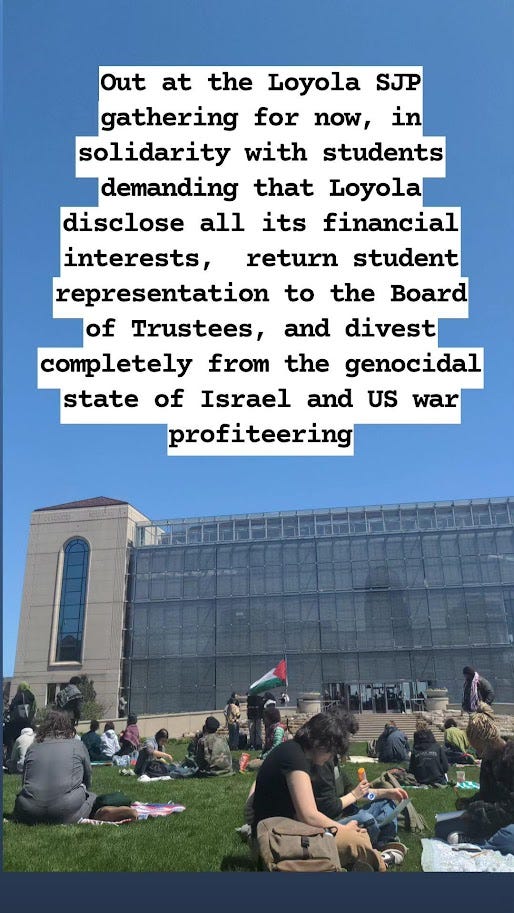

I began my day yesterday on the Eastern Quad of Loyola University Chicago, joining students, staff, and my fellow faculty in demanding that my employer divest from war profiteering and the state of Israel.

It was a peaceful, relatively small gathering that the cops did not intrude on. After about an hour there, I heard from comrades a few miles north, on the campus of Northwestern University. Their significantly larger encampment was being attacked by the police, so I hopped onto a train and shot my way up to Evanston to offer whatever support I could.

(I was joined by a member of my affinity group, someone who has accompanied me to nearly every protest, rally, illegal road blocking demonstration, and other pro-Palestinian action I’ve attended in the last few months. If you are new to more radical organizing, I strongly recommend you form an autonomous affinity group with a few trusted buds.)

We saw quite a few people carrying banners and wearing keffiyehs on the train. A young man with a Palestinian flag pin on his backpack (alongside a cute Eevee keychain) approached us, and asked if we were headed up to NU’s encampment.

“I’m planning to get off at Howard station, grab a bunch of supplies, and then make my way up there,” he told us. “Do you have any idea what specifically they might need?”

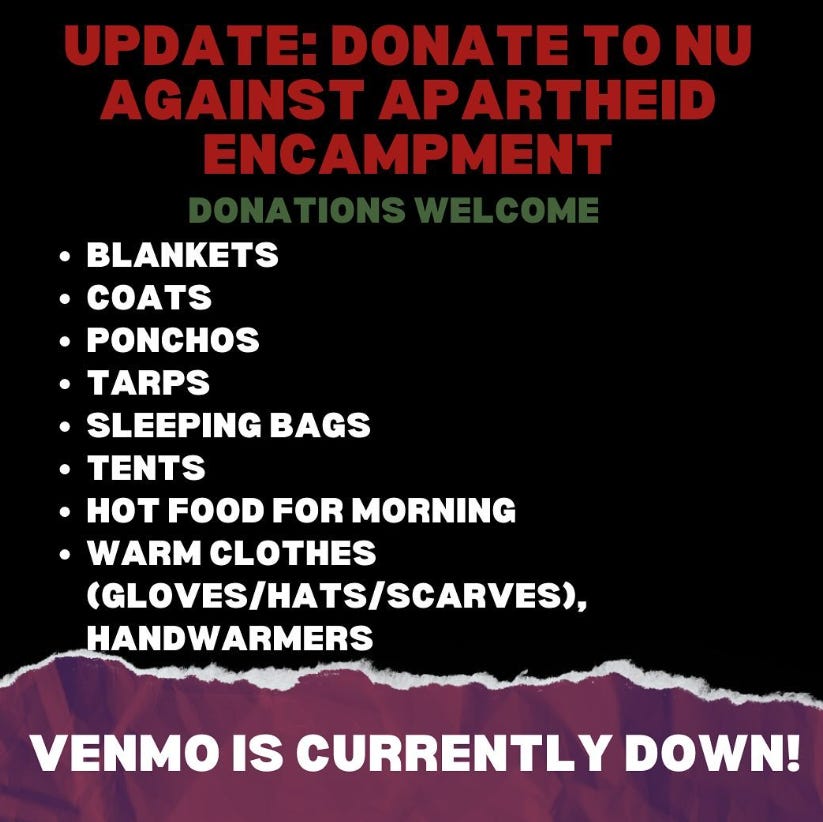

I said that I was in a group chat with a team of supporters, and that a list was being passed around. Students were planning to stay the night on the lawn of the Deering Library, and maintain a consistent presence there until their demands for divestment were met by the university president, no matter how long that might take. They would need adequate food, water, first aid supplies, sleeping bags, tarps, generators, projectors, amplifiers, hand warmers, tea, coffee, tents, gloves, toiletries, and charging cords to be able to do it. They would also need monetary donations for incidental expenses and food orders as the days wore on.

I passed this information along to our new friend. He said he’d grab some water, snacks, and painkillers. At Howard we parted ways, hoping to see one another again up in Evanston.

We arrived at Northwestern’s campus in the early afternoon. By then, student protestors and their allies had successfully fended off the police using physical force. I’ve been awed by the courage that young activists throughout the country have demonstrated this week. On campuses like Cal Humboldt and Emory they have seized university buildings, thrown desks and chairs in the paths of encroaching security forces, bonked cops in the head with water jugs, dearrested protestors, and inspired countless comrades on other campuses to follow suit.

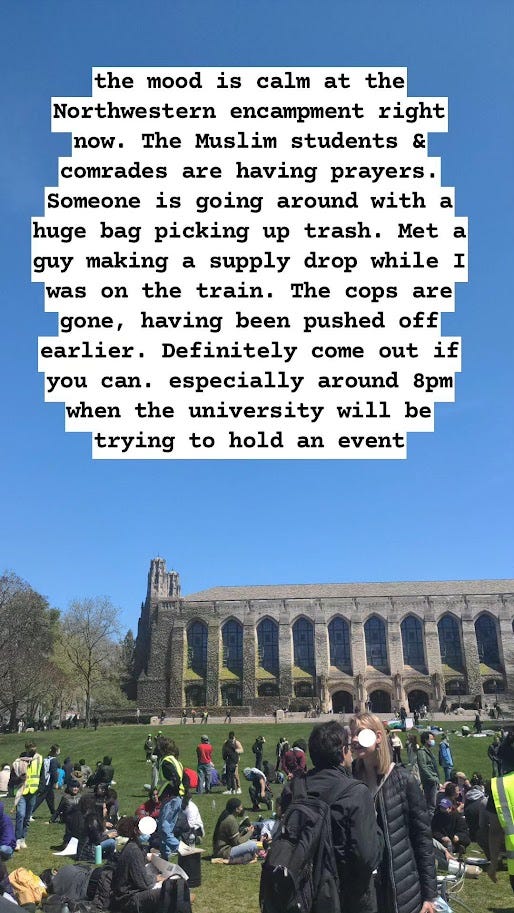

There was no police presence at all when my affinity group arrived. Hundreds of young people and community members were gathered calmly on the lawn, building up their facilities and planning for a lengthy occupation.

Wandering about the camp, I was struck by how effortlessly well-organized everything felt (and of course, I recognize that such seeming effortlessness actually comes from decades of on-campus organizing on the part of Students for Justice in Palestine and the Boycott, Divest, and Sanctions movement. It is also a credit to the lessons learned in the past few years of activism, from the Stop Cop City efforts in Atlanta to all the lessons learned in the many ongoing years of BLM activism).

A large poster-making station had been positioned in the front of the Deering Meadow fence. An older white man in a knitted watermelon hat offered free posterboard, planks of wood, markers, paint, tape, and a staple gun that he capably wielded to help bring everything together. I’ve seen him at a lot of actions this year. He helped me mount my own signs. On this day, there were hundreds of hand-drawn posters and banners, many of them attached to the fence as if warding off opposition.

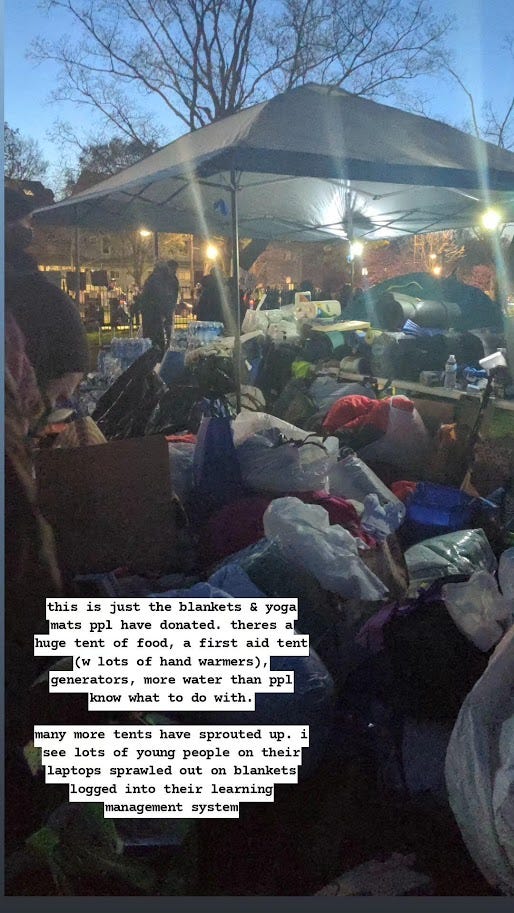

Inside the encampment, a large tent had been erected and filled with tables; they were stacked with boxes of pre-packaged snacks, pallets of water bottles, and even fresh fruit. Another receiving area was stacked with yoga mats and blankets. In the back, a young man heated water off the generator to make tea. Someone (or a few someone’s, probably) had already ordered pizza, and I could see the leftover boxes being transformed into protest signs all over the lawn. Several people walked around with massive trash bags collecting litter; they were so responsive that I had to tell people not to grab my plastic bag full of supplies multiple times.

As I circled the full lawn, I saw that entire social ecosystem had sprouted in the fertile ground student activists had developed. A gathering of young women in hijabs stood off to the side, practicing how to break free of police grips together. Speeches and chanting were being held on the speaker system. When we walked up the stairs to take a seat on a circle of stone benches, we happened upon an informal political theory discussion group.

“What does NIMBY mean?” a woman in her mid-twenties asked.

“Well, in the context of what we were discussing, it means that people do not want a wastewater treatment plant to be placed in their community, which is somewhat understandable as an impulse,” a slightly older woman in a ponytail explained.

“There’s been lots of valuable organizing against ecologically destructive developments,” someone else added. “But the ‘not-in-my-backyard’ spirit has also been applied to things like installing a wind turbine or a shelter. Most people will agree they want such resources to exist. But when it comes time to develop them, they don’t want them in their back yard.”

They all nodded thoughtfully. Then one student shouted excitedly at the sight of a squirrel attempting to steal someone’s trail mix.

There was a small gathering of pro-Israel activists standing on the far north side of the quad, looking sheepish. Some held small signs with the Israeli flag printed on them. They remained gathered together very tightly, not engaging with the crowd. For the most part, we knew to keep our distance too, and not give them any grounds to escalate. We had the numbers to drown them out, so they didn’t even bother to try chanting. After about an hour or two they had completely dispersed.

On the outside of the fence, journalists lined up. They pointed their cameras at the crowd and scanned the mounted protest posters over and over again, paying the more revolutionary and anti-cop ones the most attention. And then they lingered watchfully, waiting for something exciting to happen. One reported attempted to speak to my affinity group, asking us why we had come, but we directed him to the organizers.

“Who are the organizers of this?” he asked. I directed him to the team in the bright yellow safety vests. Yet he never broached the fence to actually approach anyone in the camp proper. For the next hour or two I saw him continue to march up and down the sidewalk, taking photos of posters, never actually engaging with the community on the other side of the fence.

On the barrier between the bike path and the road, a small cluster of young people stood banging out a rhythm on buckets, drums, and empty water coolers. A few others stood behind them holding signs that read things like Divest from Genocide and Honk 4 Palestine. The mood was so calm in the camp that my affinity group wandered out to join them, lured by the music. We stood inches from the passing cars, dancing with our posters in our hands: Land Back from the River to the Sea on mine, CPD, KKK, IOF You’re All the Same on theirs.

A white woman approached the two of us. “You know that Hamas would kill you for being gay, right?” she asked.

“Move along lady,” my affinity partner said.

“They’d kill you-”

“I bet you’d like that,” I said. “You love imagining us dead don’t you.”

“They’d kill you-”

“Move along,” my affinity partner continued to say until she lost her courage and wandered along.

We stayed moving our bodies to the drumming, cheering when drivers honked their horns and waved their own flags and keffiyehs at us. There were far more supporters driving past us than there were opponents. Every now and then a white man in an Escalade or a bloated pick-up truck would steer past us slowly, extending an impotent middle finger. But even the jeers we got were easily silenced by the cheering and chanting.

After about an hour of us standing on the line like this, a young red-headed man in a tank top and shorts came up to stand by us. “Welcome, thanks for joining us,” my affinity group partner said. A young woman drumming on a bucket offered him a water cooler container to make music on.

“I’m good,” the young man said. "I’m just here to see what this is all about. So…,” he became a bit shy. “What does freeing Palestine mean to you?”

“It means we need to get rid of all these settlers,” my affinity group partner said. “Give them all their land back.”

“Do you think the land in Gaza is enough?” the red-headed kid asked. “Like, it seems like it is so deprived. So much poverty there, it seems like it’s inevitable.”

“That’s because they’ve had their land destroyed,” I explained calmly. “All of their olive trees were burned down so they can’t farm or eat. Every single university has been destroyed. Every hospital.”

He nodded thoughtfully. “Ending this assault first is the most important thing, I guess.”

“That’s true,” I told him. “And yes, after they’ve been forced off their land and seen so much destruction, I think they would need reparations to even begin to rebuild.”

He stared out into the street, thinking for a moment. “It’s a lot to think about.”

“I know,” I said. “And you know, I used to think this topic was too complicated to take a stand, too. But then, you know, you learn.”

He let out a contemplative sigh. And then he walked over to the lawn and picked up a spare Honk 4 Palestine sign and stood beside us for some time, one of the first symbols of support someone newly arriving to the camp would see.

Cars kept pulling up alongside us to offer donations. People from all throughout Chicago, Evanston, and the surrounding suburbs came out with big boxes of yoga mats and tarps, chewy granola bars, gluten-free matzah for seder, hand-knitted blankets, even clothing and boots to protect from the rain. And bottles of water. So many bottles of water. They piled up everywhere. Eventually organizers had to send out the message that no more water was needed. The generosity of the collective created an abundance we all could trust in.

We’d been there for hours, and so my affinity partner and I decided to take a break to head into the city to use the bathrooms and eat a meal. We hadn’t learned yet that the Multicultural Center across the street was offering up its bathrooms to the protestors, since many of us couldn’t access other campus buildings without an ID.

As we walked into Evanston proper, a woman in her thirties with two toddlers in a stroller accosted us about our signs. “I’m Israeli, and I want to know if you really mean what you’ve written there,” she said. “From the river to the sea? You want to see the complete eradication of Israel?”

I held my tongue from saying that I wanted to see the end of all colonial empires, the returning of all lands, including the ones that we were standing on, to the stewardship of Indigenous people. My affinity partner told her to move along in a calm, yet authoritative tone. Then we popped into the Colectivo to use the bathroom.

The air in the city was tense. As soon as we stepped away from the main encampment we saw university administrators in suits and lanyards standing around looking bothered, and random passers-by on the street gave our signs hard looks. It had never been like this at all the actions in Chicago, even when a guy in a pickup truck once tried to mow us down in his car.

In the big city, the average person who wasn’t pro-Palestine feigned boredness with the resistance. They’d march right past a blockade of hundreds of us pretending to be fascinated by their phones. Plenty of people were downright happy and supportive. Here in Evanston, things felt more polarized. Wealthy homeowners and university bigwigs viewed our growing encroachment as a palpable threat, and they were poised to lash out. But they lacked the numbers.

More and more supporters were flooding the campus. The organizers at Northwestern had put out the call: they needed bodies around 8pm, so that the police wouldn’t attempt to push them off the lawn in the night. We knew we had to stay at least until then.

Heading back to campus in the evening, the numbers had grown. Now over 1500 people were present, dozens of news tents of all sizes had appeared, and a steady stream of speeches and chants were echoing from the loudspeakers.

As the sun set, the Muslim attendees held prayers while Jewish Voices for Peace began holding their seder. Volunteers moved through the crowd, passing out matzah, and bystanders were invited to come forward to view the seder plate. Students splayed out on sleeping bags and blow-up furniture, their laptops open and Canvas glowing on their screens.

The number of supplies and facilities in the encampment had grown massively in the final few hours of the day. There was now an entire large event tent just for the distribution of blankets and yoga mats alone. It spilled out into the surrounding area, piles of blankets and clothes resting nearby on tarps. There was a medical tent with a small treatment area for injured students, and a volunteer passing out aspirin, hand warmers, band-aids, and the like. Someone had created a makeshift porta-potty using a tiny tent and a bucket. The food was overflowing and so, still, was the water, La Croix, and juice.

Night fell upon the camp and my affinity partner and I pushed our way gently through the crowd, taking everything in. A long row of undergraduates stood off to the side, learning how to dance the dabke. Some boys circled up and kicked a soccer ball around. Young people studied, cuddled, ate, slept, and worked on their assignments. It felt like the early days of Occupy Wallstreet and my first week as a freshman at Ohio State and a music festival all rolled into one.

Ohio State was launching its own encampment at the same time, hundreds of miles away. Snipers waited on the roofs of the Union, poised to attack. My heart yearned to be back there, at the messy, well-resourced city of a Big Ten school that made me the psychologist and activist that I am today. But here at Northwestern, the situation was calm. No police arrived to harass students that evening.

Student activists told us that we were welcome to remain at the encampment for as long as we wanted, but that only people affiliated with the University were to sleep there over night.

As my affinity group left the campus at around 10pm, we received a message: there was word that the cops would be arriving and making arrests as early as 6 am. Comrades were to arrive by 5 or 5:30 in the morning to offer our support and our numbers to prevent any arrests from happening. Throughout the night the sprinklers went off on the lawns, dampening some supplies and some sleepers but never breaking up the resolve of the camp.

Thankfully 6 am came and went with no suppressive action from the cops. Once again the power of the people came through, and made the risk of escalation so great that university administration and the police state were deterred. The Northwestern Liberation Zone had established itself as weighty, diverse, and built to last, a feat of ongoing organizing and solidarity across a variety of campuses. At the time of this writing, at 12:30pm on Day 2 of the encampment, it is still going strong, with thousands of people having visited to lend their support.

If you would like to donate to the Northwestern Liberation Zone, you can do so on GoFundMe.

This was great. Thank you for taking us with you on this experience. Definitely squeezed the water from my eyes!

Also, 🍉