Getting Involved & Staying Regulated

Finding your place in the fight for Palestinian lives - and remaining there when it gets tough.

Like a lot of people, the genocide currently happening in Gaza has stirred me to take action — but has also frequently left me at a loss as to what I might do.

As a white American, I recognize that a portion of my tax dollars go toward supporting the Israeli government’s bombings, raids, and ground invasion into the strip, and that my own government and its military has a hand in the attacks that have left (at the time of this writing) over 8,000 people dead.

I am staggered by the sheer scope of the bloodshed, and the wanton brutality of it. Children photographed seeking cover from air raids are found dead by journalists mere days later. Hospitals in the Gaza strip overflow with bodies, both dead and ailing, who are in that position because of the Israeli government’s choice to cut off water, electricity, fuel, and other necessary resources to the region while they batter it with munitions and gas.

I also recognize that the United States itself began as a colonial ethnostate, much as the state of Israel did, and that it used (and continues to use) the same tactics of breaking treaties, encroaching upon territories, terrorizing Indigenous peoples, and destroying their homes, landmarks, and other cultural touchstones in order to further the mythologized supremacy of its nation-state. The violence of history echoes, the tactics of the Trail of Tears, Apartheid, and the Holocaust effortlessly mimicked today by nationalist governments, each form of oppression linked to those of the past by a chain of white supremacy and capitalist greed.

I’m living comfortably in a warm, well-supplied apartment on North American land that has been steadily covered by European plants and populated by European people over the course of the last few centuries, all while Indigenous peoples throughout the world have had their languages, practices, homes, and families destroyed. I cannot help but recognize there is blood running like a river under my feet. But since I also live in a country where meaningful political participation of any kind is systematically thwarted, I often struggle to conjure up what taking meaningful steps to set things right might look like.

I have been pro-Palestine as far back as I can remember; in college, a boyfriend who majored in Hebrew and I frequently came to verbal blows over the actions of the Israeli government. After learning just a sliver of the history of the region, the moral calculus was already clear to me: it was wrong for a people to be forcibly removed from their homes, shunted in vast numbers into a walled open-air prison, and assigned a completely separate political and carceral justice system from that of the people who now lived in their homes.

At the same time, I felt unsteady in my lack of expertise. The history and the geopolitics seemed ‘complex,’ even if my fundamental values weren’t. And so for a long time, I never trusted myself to speak at any great length about the plight of people in Palestine, or even to condemn the actions of the Israeli government with the level of fervor that I really thought it deserved. I never wanted to accidentally parrot antisemitic talking points, or erase the existence of non-European Israeli people by discussing the colonialism that took place in the region with too broad a brushstroke.

I was confused and cowardly, but also appropriately humble. I knew I could not trust myself to represent the interests or many perspectives of the Palestinian people well at that time. But now isn’t the time to remain silent out of a fear of stepping out of one’s lane or making mistakes. Thousands of people have been killed, the majority of them young people and civilians, and the Israeli government has invaded what remains of Palestinian land, spiting much of the world’s demand for a ceasefire. It is important to name this genocide for what it is, to speak out about its egregiousness and evil, to honor the lives that have been unfairly stolen, and to inform oneself about their identities, their culture, and their history while taking action to prevent further loss of culture and life.

It is also important to go about supporting the Palestinian cause in the right way. On social media, I see countless people like me feeling guilty, uncertain and overwhelmed, posting in an endless fervor: they’re sharing infographics and Tweets of unclear provenance, scolding one another at times for not posting enough, recommending that donations be made to large, European- and American-owned humanitarian aid organizations, and advancing a panoply of political tactics that don’t always make sense alongside one another.

Should I call for my Senator (military veteran Tammy Duckworth) to vote for a ceasefire, when I already know she’s a stalwart support of Israel’s “right to defend itself”? Or should I blockade an arms facility? Should I disseminate a flyer about an upcoming protest and film myself there so that I’m clearly taking a stand, or should I avoid broadcasting such actions on outlets where the CIA might track me and others? Should I participate in a boycott or a general strike, though it’s unclear how widely organized such actions are, and whether the economy will feel their impact if they aren’t? Is a ceasefire the right outcome for me to demand, or do some movements framed as seeking “peace” concede Israel’s authority over the region in unhelpful ways?

Many people like myself want to make a difference, but are not exactly sure how, and so they believe nearly everything that they hear and they commit to every angle of the cause with about equal energy, and none of it sustainably. We have been down this road before. In 2020, numerous well-intentioned would-be allies to the Black Lives Matter cause posted symbolic “blackout” squares to their Instagram profiles with the #BLM hashtag, intending to broadcast their support, but in practice suppressing the distribution of information by clogging up the feed and making the hashtag useless to track.

In 2016, after Donald Trump was elected, would-be allies to Muslim people adorned their jackets with safety pins, hoping to signal to anyone being targeted by Islamophobic violence that they were a “safe” person to approach for help. But did it make sense to expect the targeted members of a marginalized group to carefully scan every stranger’s lapel in search of an ally, rather than demanding the allies rise up and find them?

Were all these calls, each so popular on social media, as beneficial to vulnerable people as they were effective at assuaging privileged people’s tough feelings? When we are filled with panic and bombarded with triggering information that changes moment by moment, how do we retain the ability to discern what’s true? Are we searching for a way to make a difference, or are we looking just to feel that we have? How do we go about getting involved, and staying involved in a way that really helps without succumbing to privileged withdrawal or numbed jadedness?

I won’t profess to be an expert on everything that the Palestinian people need. And I do not have to be in order to speak out, because I have surrounded myself with sources of information and calls to action that I have carefully vetted and can actually trust, and because I am an engaged enough student of history and politics to have formed a working understanding of the types of change I believe in, and the tactics that make such change happen.

I know when to filter my information intake, because there are limits to how much a person can meaningfully process, and how to separate my unique gifts that I can contribute to the movement from the calls for action merely for action’s sake. I set limits on my social media activity so that I do not waste too much energy on posting that could be spent elsewhere. I recognize where I specifically am positioned to have the most positive impact, and I focus my attentions there without beating myself up much for not being capable of everything else.

As a former badly-boundaried white savior “activist” type who used to overcommit and under-deliver in endless boom-and-bust cycles, it has taken me a long time to develop this clarity of purpose and no-nonsense political discernment. I am no longer so self-important as to expect myself to be everything in order to do anything, and now I can take comfort in finding the handful of ways to address this genocide that I can consistently make.

I thought that one way that I might help other potential pro-Palestine activists in the making is by sharing what I have learned. So here is my advice for how you might go about finding your own unique place within a growing political movement — and staying within it for the long haul.

Choose Your Information Load Carefully

Today, the average person who uses the internet consumes more information in a single day than our great-grandparents would have consumed in months (and more information than a 15th-century person would consume in a lifetime), much of it very poor quality information that is either misrepresented, or will not remain relevant within a few hours. And contrary to the cliché, knowledge is not always power: when people consume the news excessively, they are more fearful, disempowered, distracted, and more likely to fall prey to misinformation and scams.

It is quite easy during moments of international crisis and mass death to get caught in a spiral of doomscrolling, flooding one’s nervous system with debilitating amounts of cortisol and bombarding one’s thinking with a haze of junk data, all in the pursuit of keeping oneself responsibility informed. We all make this mistake sometimes, because social media sites are designed to function like slot machines, training us to keep searching and sharing, without encouraging time to reflect.

Even our friends and loved ones encourage us to maintain this self-defeating cycle at times, telling us that if we aren’t paying adequate attention to an issue, it must mean that we don’t care as much as they do about it — even though there is a very real psychological limit after which more information consumption is not helpful.

I still make this mistake myself. Earlier this month, I was disturbed and outraged by the sheer number of unsourced claims and outright misinformation being promoted by mainstream news outlets and on social media regarding the attacks by Hamas, as well as Israel’s retaliatory bombings. So when I saw a friend sharing an article in an outlet called Mind’s Eye Mag calling out several high-profile instances of misinformation, I looked it over, and thought it might be beneficial to share.

But as I read more deeply through the site, I realized Mind’s Eye Mag wasn’t a reputable source in the least; after clicking through a few pages, I was recommended articles from the neo-Nazi website The Daily Stormer. Thousands of people had already shared this Mind’s Eye Mag link, being tricked into spreading genocidal hate in their desire to condemn the very same thing.

This served as a harsh reminder that I can’t parse information very well at all when I’m swept in the heat of alarm. Though I felt an urgent need to speak out against injustice, it was my urgency that led me astray, and that brash action harmed Jewish people who are in no way reflected by the actions of the Israeli government, as well as the pro-Palestinian cause.

It is always far better to take a moment to carefully process what we are reading, to step away and digest the newfound knowledge, to check it against our existing knowledge bases to see if it makes sense, to discuss what we have learned with others, and to be intentional about what information we choose to disseminate to others.

This doesn’t mean we should stop sharing information. Palestinian journalists and everyday people on the ground are broadcasting images of the dead because they want the international community to take notice — and because much of the news media has deliberately shied away from reporting on the death toll, even as it continues to mount.

In light of this, I believe that bearing witness to the suffering of Palestinians is respectful, and that amplifying their cries of grief and their calls for justice is an appropriate thing to do. It isn’t trauma porn, it is humanization. It honors the lives lost to reflect upon them, to see their faces and know their names.

At the same time, merely bearing witness to mass death is not sufficient, and being saddened or horrified is not itself a moral act. Only our actions can be moral, our emotions alone never can be — and so if you find yourself caught in an endless loop of viewing images of dead bodies and demolished buildings and it leaves you too incapacitated to act, you should set a limit on how and when you consume such imagery.

If viewing such images dysregulates your nervous system so much that it prevents you from taking actions to help Palestinian people that you otherwise would, you don’t have to look at them. Your actions matter more than your feelings — as an Autistic person who lacks empathy but cares about stopping genocide, I cannot emphasize that enough. Find the means of staying informed that prepare you to take action rather than freeze you, and don’t equate being upset with having actually committed a moral act.

Be Selective in Your Information Sources

If you wish for knowledge to be empowering and clarifying to you rather than overloading and misleading, exercise good judgement over which information sources you will turn to. Instead of prioritizing sheer volume and spending all your time online treating all posts about Palestine equally, be selective about the information sources you take in.

I have learned a lot about the history of the Palestinian people and about the present day-struggle from Hasan Piker’s streams. He’s extremely well-versed in the topic and has been passionate about it for years, which lends him a credibility that many who are new to discussing the region lack, he reports on new developments daily and in depth, and he’s a leftist whose political beliefs align closely enough with mine, so I find his analysis of what’s happening helpful.

Just today, for example, I learned from one of Piker’s videos that the Jewish communal farmers who live on kibbutzes in Israel tend to be overwhelmingly pro-Palestine, and that the Israeli government positions them on the fringes of the country as a kind of human shield against attacks from Hamas.

This helps explain why some of the Israeli hostages that were taken from kibitzes by Hamas have been so sympathetic to Palestinians, and have been so outspoken about not being abused while in custody. It also reveals how craven the Israeli government can be, even in its treatment of its own citizens.

Equating Israeli citizenship with opposing the rights and welfare of Palestinians is completely misleading, and Hasan’s coverage reminds all of us of that. Numerous people within the country have been on the right side of history and have called for the end of the apartheid-like segregation and exclusion of Palestinian people for decades, just as many Americans support Indigenous people and the Land Back movement here. It is the Israeli government that would prefer we all believe otherwise, and who aim to equate Jewishness with support for the Israeli nation-state.

I have also learned a great deal about the struggle of Palestinians from Dr. Ayesha Khan, who writes on Substack under the moniker Woke Scientist. She’s been an outspoken support of Palestinian people from years; some of our earliest private messages with one another were about Instagram suppressing her account for making posts sympathetic to the plight of Palestinians.

It was Ayesha whose work reminded me that a call for a ceasefire is inadequate: while of course I desperately desire for the violent onslaught against Palestinian people to cease, to end this conflict with just a ceasefire would be to return to the oppressive status quo that has left millions of people trapped in Gaza and the West Bank without any power of political participation or even the right to leave, let alone to return to their ancestral homes.

After a genocide that’s killed thousands of people, a return to superficial, unjust “peace” will not cut it. I learn constantly from Ayesha’s compassionate, thoroughly informed writings, and she challenges me to be a more steadfast and fully-read ally to Palestinian people in all the best ways.

After the Israeli government shut off internet and cell phone access in Gaza, I also turned my focus toward the few journalists still on the ground who had access to sim cards: their videos of the otherwise completely blackened night sky of the strip aglow in bright orange bomb fire was one of the only remaining lifelines into the region that any of us had. They were putting their lives on the line simply to ask the world to hold vigil over the rubble. Lending these moments of destruction my attention did not feel traumatizing or grim, it felt like choosing to be a party to justice, rather than being complicit in the Israeli government’s attempts to purge all remaining gasps of life away.

As you filter through the constant din of news and posts about this ever-changing geopolitical catastrophe, it always bears asking yourself: Do I trust the judgement of the person sharing this information? Do I trust their knowledge base? What is this person’s ideology, and how might that inform their views and what they share? Does this information make it easier for me to get involved, or does it make me feel confused, guilty, and unfocused? What does the person sharing it stand to gain by sharing it?

Your answers and impressions might not always be the same as mine, and that is okay, because we are different people with different positionings in the world, and there are different ways in which we are primed to make an impact. I defer to leftist, anti-colonial writers, though there are others whose work I will sometimes draw upon if I want to convince a more moderate-leaning relative that Palestinian people must be included in Israel’s political system at a minimum if any long-term, remotely just peace is going to be attained.

You may find that your information needs are slightly different from mine based on the work that you are doing, your familiarity with the topic, and your own working understanding of what meaningful political change looks like.

Furthermore, Palestinian people are a diverse group with a variety of viewpoints. Some believe that the best thing that an American person can do right now is call their political representative to politely request a ceasefire, others believe we should be rallying in the streets to demand the same outcome, and still others believe that all colonial empires including the United States need to be abolished in order for anything resembling justice to be reached.

Given this, I find the call that we merely “listen to Palestinians” to be unproductive when it’s not also grounded in a deeper historical and political understanding that allows us to determine whether a person has a similar vision of change as we do. I can’t read everything, and not every perspective is equally relevant to my own goals or capabilities. Filtering my information sources down to the ones that empower me to take the actions I believe in is tactically sound and responsible. This brings me to the next piece of advice:

Study History

The study of history grounds me, and lends me perspective. Taking in all the latest news updates without a broader frame of reference for what’s happening can be like trying to catch individual grains of sand between ones fingers: learning the history of the region, the movement, and about how similar political movements have succeeded or failed in the past provides a deep, high-walled bucket in which to catch all those sediments, and contain them.

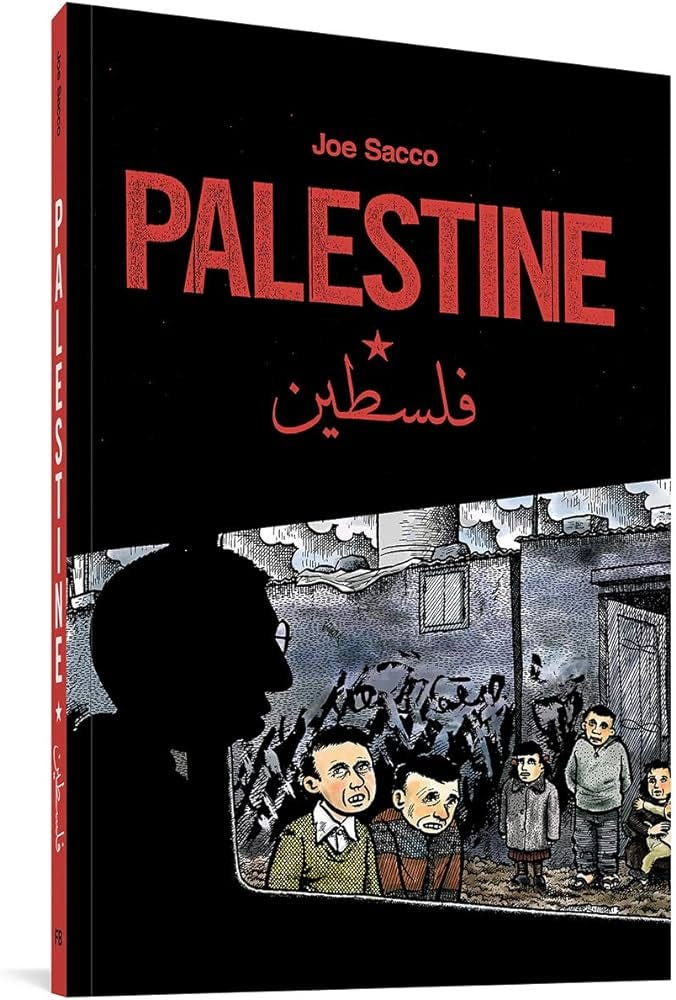

Purely by chance, the comic book club that I’m in recently read Joe Sacco’s Palestine, a graphic novel written in the 1990s that provides a humanizing portrait of what daily life was like for those trapped in Gaza’s under-resourced, open-aired prison during that period. I and everyone else in the comic book club found the novel clarifying: in Sacco’s many visits with Palestinian families of all sorts, we could grasp what the true impact of Israel’s draconian policies against their people was. It wasn’t a dry historical account, it was a series of very small personal stories, and that made it more manageable to process and more possible to fully feel.

Reading the statistics about Palestine can numb the brain with sorrow: over half of Gazans are children, due to the region’s deprivation and high mortality rate; it has one of the highest population densities in the world, because nearly ten thousand square miles worth of people have been forcibly contained within a strip of land the size of Chicago. It’s more collective pain than any person can comfortably imagine. Small narratives of individual people breaking bread with Sacco and telling him of their murdered brothers and mothers and their recent weddings helped made it all concrete. It kept me from becoming numb to the enormity of the carnage.

I have also learned a great deal about the political history of the pro-Palestine movement (and the Israeli government’s suppression of it) by listening to the podcast True Anon. In a recent episode, journalist Noah Kulwin reports on the many tactics the Israel lobby has taken in the United States to suppress criticism of their government.

A growing movement of young Jewish college students have spoken out against the oppression of the Palestinian people, likening their exclusion to South Africa’s Apartheid government, but the Israel lobby has vigorously suppressed this, discouraging journalists from ever covering their abuses against Palestinian people, and even bringing Black South African activists to their country to try and convince them to make statements drawing a distinction between the plight of the Palestinian people and their own.

Learning about the history of the Israeli government, its genocidal tactics against the Palestinian people, and its numerous attempts to silence even American Jewish criticism of its actions helps me to be a more effective advocate for the lives and wellbeing of Palestinian civilians. I have a better sense of what we are up against as a movement, how we got here, and what has not worked in the past. That makes the present situation more explicable to me, and it also ensures that I don’t misuse my time. That brings me to the next tip:

Study Political Strategy & Tactics

I cannot follow every political call to action that passes over my social media feed. Nor would I want to — in the early days after Trump was elected, I spent an hour every single day calling political representatives all across the country, sharing my opposition to everything from the removal of protections for LGBTQ students to the caging of immigrant children at the border. My hope was to help, but I’m not sure these days that it was the best use of my time and energy.

Calling political representatives can make a difference — all my friends who have worked as staffers tell me this. Specifically, they say that some politicians are moved when they are on the fence about a particular issue and then get overwhelmed with a deluge of letters and phone calls that make them realize an issue is far more near and dear to their constituents than they ever thought.

But ringing up a Congressperson who is conservative or decidedly pro-militarization is unlikely to make a huge difference, since they’re going to presume they’ve lost my vote already and they have a massive financial incentive (thanks to the Israel lobby) to not change their allegiance. Beyond that, when I believe the root cause of the genocide against Palestinians is the inherently violent dehumanization of the nation-state, then making appeals to another massive, genocidal nation-state in order to stop it doesn’t necessary make sense.

When our elected representatives are not accountable to us, we must escalate and take an approach that forces them to contend with our collective power and rage. In this, I draw inspiration from the work of ACT UP activists, who stormed federal buildings and covered the homes of Senators in gigantic prop condoms, and in the medical advocacy of the Black Panthers, who established free clinics that provided sickle cell anemia screenings, contraceptive care, and even basic first aid training to any oppressed or impoverished person who walked through their doors.

When the state massacres innocent civilians on a massive scale, we must be disruptive, and when our efforts at political outreach are stifled, we must be willing to get subversive, too. It is the study of history and of political tactics that has made me aware that the Israeli government does not want to broker a simple peace with the Palestinian people, or to listen to their cries for full legal standing.

In 2018 and 2019, Gazan people held long, peaceful protests at the border wall, as part of a movement called the Great March of Return. Independent activists organized these weekly demonstrations against Israel’s blockades of the Gaza strip and over 30,000 people gathered at them, demanding the ability to return to their homelands. Those who have closely studied Palestinian resistance mark the Great March of Return as an important turning point, away from more violent resistance and toward more symbolic, civil disobedience.

It didn’t work. The Israeli government tear gassed the demonstrators, and shot at them, killing over 200 people and injuring thousands with live ammunition to the arms and legs. The United Nations condemned these senseless killings, but the United States used its veto power to block the U.N. from conducting an investigation into the civilian protestors’ deaths. In advocating peacefully for the right to return to their lands and to move freely as citizens throughout their own country, Palestinians have already exercised every viable option, and seen it fail and be violently punished, repeatedly.

Similarly, the study of politics and history has informed me that the Israeli government had a hand in creating Hamas, financing the Islamic group and favoring it over the more secular and popular Palestinian Liberation Organization (the PLO). Because the PLO represented a diverse faction of Palestinian people and their interests and was far less militant, it garnered far greater support, and stood a far stronger chance of accumulating the political capital it needed to negotiate serious victories on behalf of the people in Gaza.

This was unacceptable to the Israeli government, who propped up Hamas as an adversary far more worthy of violent ire. Even some former Israeli government officials have explicitly stated that Hamas was an “Israeli creation.” In its past military actions against Hamas, Israel killed over 2,500 people. That large number now dwindles in comparison to the over 8,000 Palestinian people killed in just the past month.

A study of political history and tactics teaches me that convenient, respectful forms of protest in favor of Palestinian rights have historically never been honored, and that in both America and Israel, politicians have every incentive to turn the other way when the people speak out in favor of Palestinian life. A study of the abuses of Indigenous people here in the United States offers much the same lesson; when Native tribes negotiated peace with the U.S. government and assented to being moved onto new lands, they were only ever betrayed and met with further violence.

Due to this knowledge, I believe that we must not carefully bend our political representatives’ ears and ask them to suddenly develop a conscience that goes against their every source of power. Instead, we must organize collectively to fight the oppressive violence of both our nation-states, and be willing to break unjust laws when necessary in order to preserve life.

That’s a far larger, vaguer purpose to set out for oneself, compared to the simple ask of calling up a few politicians and praying for peace. But it’s clarifying for me. It means that I am in this battle for the long haul, and that progress towards justice will not be found after issuing one statement or attending one protest. I can move somewhat slowly, so long as I remain in the struggle, recognizing that my position within the larger movement for Palestinian life will be quite small.

Much of the progress that I must make lies in simply informing myself about the true nature of the Palestinian struggle, because most media outlets I am familiar with and the schooling institutions that I attended as a younger person all deliberately have left me in the dark. Once better informed, I have the power to educate others, and to help them see the connections between Indigenous history here on Turtle Island as well as in Palestine.

When we can recognize that each of our struggles is connected, our battles come into focus as much larger wars against injustice — but we also become aware that we are far less alone than we might have previously believed. Every step that we take against one form of oppression can in turn help to vanquish another. This brings me to the last tip I have for budding pro-Palestinian activists, or new activists of any sort really: finding your own unique place in the fight, and making peace with the fact that your impact will always be small.

Find Your Own Humble Place in the Fight

Yesterday, an Autistic person messaged me on Tumblr, asking how they might develop the social skills necessary to participate in revolutionary political actions. They shared that they wanted to be directly involved in the fight for Palestinian liberation, but that they didn’t quite know how to engage with other people at organizing meetings, or how to weather the massive conflict that inevitably forms when you get a highly passionate, traumatized group of activists together and try to form decisions among them.

I had so many thoughts on the topic that I didn’t even know where to begin. My entire next book, Unlearning Shame, examines how people who feel stuck and overwhelmed in the face of massive systemic injustices can slowly start building a way outside of their own heads and into the broader social world, so they might advocate for the change that we all need.

I wrote the book because I find organizing with other people quite difficult myself — there is always more to be done, and not enough energy to do it all, and though I’ve slowly begun to develop the skills necessary to converse and engage in conflict with people, being vulnerable and standing in community is still hard. But asking an aspiring Palestinian activist to read an entire book on social and political self-advocacy didn’t feel practical right now, especially when I’d rather them catch up on Palestinian history first.

Thankfully, Tumblr user AsStrongAsYouThink offered up a far more practical recommendation: “Getting involved in ways that involve talking to people is good,” they said, “but if you want to start smaller and there’s a march or rally near you, you can show up and do little to no talking with other people.”

I think that suggestion was right on the money. Showing up in solidarity with the Palestinian liberation movement is one of the best ways that a person can start expanding their comfort zone as a budding activist while also making an evident difference. Attending a protest also allows you to make contact with other people who believe as you do, and to become acquainted with organizations that are taking further steps toward justice, and this can help you to grow in your activism as your comfort level and knowledge base expands.

The presence of each person that shows up to a protest is powerfully felt. Whether or not you interact with anyone else, regardless of whether you even have the courage to join in a chant, your existence within that space sends a message. Your existence there helps other activists feel less alone, and it broadcasts to the international community that we are all watching the genocide that is happening, and that we care.

This is why even the organizing of young people on Roblox holds significant meaning, though a protest held on a video game platform by definition is not disruptive to the powers that be. By gathering in such massive numbers, protestors flex the true, untapped power of the people; it’s the first step toward truly organizing the masses for a larger movement toward change. It is not the change unto itself, but it encourages people to begin to think more collectively, and to behave with an interest toward the communal good.

Each one of us enjoys a unique position through which we might advance positive change, humble though it might be. Rather than holding our individual selves to impossibly high standards of productivity and perfection, we can recognize that we are small individuals with limited power and sometimes even limited knowledge about a pressing geopolitical situation, who nonetheless have privileges or special gifts that we can help lend to the cause. When we see our work as shared, and appropriately humble ourselves as neither the stars nor the saviors within this story, we can find a place in the fight that’s sustainable in the long term, and that takes optimal advantage of what we do have to give.

I am happy to attend a protest and a political action meeting, but it often feels that such forms of participation benefit me just as much as they serve the political cause. The pro-Palestine rally I attended this past weekend quieted my mind and gave me a space to pray for the lives taken by Israel’s ground invasion while feeling less miserably alone.

It brought me comfort to see thousands upon thousands of people joined together in mourning the dead and affirming that one day Palestine will be free. I felt tiny in the crowd, and grateful for my smallness, for it meant I was a part of a far larger groundswell that knew better than me, and had greater potential than I ever would have alone. I’d never seen so many children present at a protest before, many of them directly leading the chants and marching with confidence as they held their Palestinian flags high. They summoned in me the courage to be outspoken even while reminding me of how much larger than my life this battle for justice was.

As an individual, my particular strengths lie in the realms of research and writing. And I’ve found ways to utilize those personal skills to contribute to Palestinian liberation, too. Over the course of the past few weeks, I have put this skill to work by carefully researching Palestinian aid organizations, to find ones that are reputable and put funding directly in the hands of Palestinian people themselves.

I know a great many people who would like to donate to Palestinians who lack food and adequate medical supplies right now — but I’m also highly suspicious of most humanitarian aids organizations run out of the US or the UK, because they’ve historically played a large role in advancing colonialism. I have also learned that most nonprofits are forced to capitulate to the state governments and liberal foundations that help fund them; it is incredibly difficult for a formally recognized nonprofit that is reliant upon grants and foundations to do any work that’s truly revolutionary. (The book The Revolution Will Not Be Funded is an excellent primer on this; I’ve also written a review of the book that summarizes its key points.):

How Nonprofits Stifle Meaningful Change, and Why

A review & discussion of the book The Revolution Will Not Be Fundeddevonprice.medium.com

Because so many sources of foreign aid for Palestinians are suspect and limited in their power, I cast about far and wide seeking mutual aid organizations local to Palestine that were not controlled by foreign governments. I found two: Gaza Mutual Aid, and the Palestinian Social Fund.

Both of these are volunteer-run, Palestine-based groups with zero overhead expenses and no formal gatekeeping over whom receives their help. Gaza Mutual Aid asks donors to send financial support into the hands of specific Palestinian people directly, whereas the Palestinian Social Fund supports farming cooperatives in Gaza and provides food and other supplies to people in the region.

I was happy to devote my energies to researching these options, and then to promoting them on social media. In the days after I spread the word about them, I watched as my efforts were snowballed by the generosity of other people, and the size of the Palestinian Social Fund’s donation pool expanded from $13,000 to over $16,000. My streaming partner Madeline held a fundraiser for the Palestinian Social Fund on Twitch this past Friday, and in just over three hours we collected $678 in donations. A day later, I matched those donations, bringing the total we raised to over $1,300.

Of course, I only decided that it was important to look into local aid organizations after Madeline suggested we fundraise for Palestinians on the stream. She served as a positive influence that pushed me to find a way to help others that actually was within my means. In the early days of Israel’s attacks on Palestinians, I felt powerless and out of my depth. But eventually, with her and others’ help, I realized that I did have the capacity to make a difference, and that the kind of difference I would make could empower others to take action too.

There are so many ways that we can resist the genocide of the Palestinian people, no matter where we are sitting in the world, and how much power we have. For those of us who are Americans, resisting this onslaught of militaristic violence can be as subtle as scamming the IRS on our taxes, so that less of our income goes toward funding unjust wars. Or it can be as overt as publicly donating a portion of our earnings to Palestinian charities, as I’ve seen countless writers, servers, professors, DJs, public speakers, technicians, and actors in my community do.

The sheer scope of the violence occurring right now is staggering, but so are the opportunities to speak out, condemn ethnonationalism, educate other people about Palestinian history, provide support to those who have faced harassment or retaliation for standing by their principles, and slowly seed the ground for more significant, paradigm-shifting change.

Publishers like Verso Books are giving away free electronic copies of their titles on Palestine. Employment lawyers are offering pro-bono services to workers who have been fired for speaking out about what is happening Palestine. Numerous leftist podcasters and streamers have devoted their every moment of broadcast to covering the region since Israel’s attacks began. Friends of mine who were far from confident in their knowledge about the subject a few weeks ago have now dedicated much of their free time to learning more about the history of the conflict, and to passing on what they’ve discovered to others who are on a similar journey of learning.

Each one of us shares in the task of resisting nationalist oppression. None of us can be expected to wage this battle alone. I think that fact is important to remind ourselves of, especially those of us who are white or American and have therefore repeatedly been conditioned to think of ourselves as the all-powerful centers of the universe.

Individualism leads us down the path of isolation, of greedily hoarding resources so that we might protect ourselves and nobody else, and viewing all outsiders as our mortal enemy — it’s the kind of thinking that leads to the very genocide that we are witnessing today. But we don’t have to choose that path. We can accept the humble smallness of our lives, and our efforts, and be thankful that we get to rely upon other people even as we extend our hands in aid to those who are suffering most acutely.

I cannot pretend to know what any other person’s specific political calling should be. I can only speak to what I have witnessed and learned along my journey, and describe the modest crevice that I have carved out for myself. If you’re feeling overwhelmed with responsibility and guilt as the attacks on Palestinians continue to mount, I hope that you can come to accept your own limitations while remaining engaged in a virtuous struggle against oppression, too.

Stay informed. Be a conscious, engaged student of history, rather than a passive consumer of content. Choose your sources wisely. Discern between the calls to action that are worthwhile and those that are not a strong fit for you. Find the meaningful difference that only you can make. Surround yourself with others who care so that you feel less alone. And grant yourself grace when you become tired, stressed, confused, or even temporarily hopeless.

Remember that we are locked in a battle that will not end quickly or simply, and so we must participate in ways that can last for the long haul. Get rest. Find time to nurture your energy and restore your compassion. Take charge of your own efforts, as well as your own self-regulation, and know that no one else can determine the course of action that is best for you. Every single one of us belongs in this fight. Every single one of us has something to give. And together, it is enough.

To support the Palestinian Social Fund, make a donation here.

Thank you very much for writing this.

Your work here sustains me Devon. It pulled me out of an inertia in a healthy way. Much love ❤️