A review of bad straight takes on bisexuality.

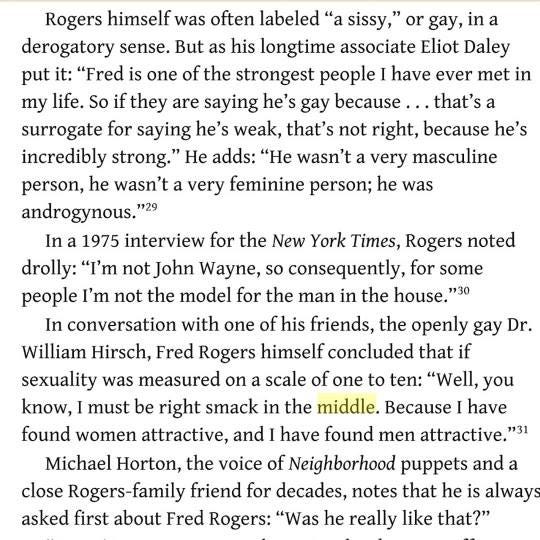

This week, a crucial excerpt from the book The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers has been making the social media rounds. In the book, published in September of last year, the subject of Rogers’ sexual orientation is broached by his friend William Hirsch. Hirsch and Rogers apparently had several private, recorded interviews over the course of their friendship, and in one, Rogers described his orientation this way:

Like many people, I was pumped and elated to read this passage. I’ve always cherished Fred Rogers; soft-spoken, kind men like him have been integral to my accepting the aspects of my identity that are male or male-adjacent. I always loved his delicate mannerisms and soft, tender voice. As an adult, I’ve come to appreciate how his kindness was paired with courage on matters of racial justice and educational access. I feel vindicated that I’m not the only person who perceived him as specifically androgynous. And as a bisexual person, I’m thrilled to find that he and I had that in common.

And like many people, I did take this passage as an indication that Rogers was bisexual. And here’s where it gets tricky. A lot of people took a lot of umbrage at the idea that Rogers was bi. And their umbrage, for the most part, took one of three forms —all of which are very common for bisexual folks like me to encounter. Here are a few examples:

The “all people are bi” dismissal.

This kind of comment is typical bi-erasure 101. It’s the one I find most annoying, because it attempts to erase the existence of bisexual people as a minority group that suffers from prejudice at the hands of straight people. If all people are bi, the logic goes, no one could be oppressing bi people! And, even more dismissively, if all people are bi, then it’s not something to remark on, so bisexual people better shut the hell up.

I hate this kind of take. It implies that an identity that is still frequently erased, and which for so many of us was only embraced after years of internal struggle, is no big deal and widely accepted. To say that “everyone is bi” is to deny the fact that bisexual people have been denied, time and time again, in media, in how we raise our children, and sometimes even in queer activism.

To say that “everyone is bi” is to claim, in a paradoxical way, that no one is. It’s similar in vileness to when parents tell their queer children that their feelings must just be a phase, and that everyone goes through it. Everyone feels this way is a fancy way of saying no one should talk about it.

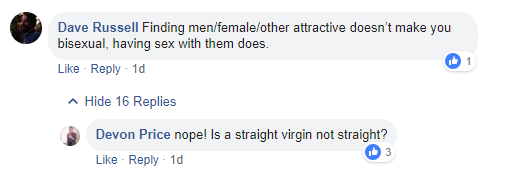

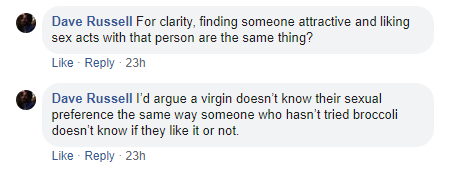

The “sexual activity is orientation” argument.

This is also an infuriatingly prevalent knock against bisexual people. It moves the goalpost of identity, and renders a person’s own description of their feelings irrelevant. And that’s particularly toxic and disgusting, because it implies that bisexual people — and queer minorities in general — are not allowed to name what they feel or what they desire. We can’t trust our own feelings. Thus, we can’t knock anything until we have tried it.

And if queer people can’t claim to have an identity until they have tried every alternative… we’re well on our way to suggesting reparative ex-gay therapy then, aren’t we?

Bisexual people often have this line lobbed at them. But it’s also used, in a deeply menacing way, to invalidate the identities of gay men and lesbians. I’ve most heard it thrown in lesbians’ direction: how can they know for sure that they don’t like men, if they haven’t given it a shot? The implication is that the lesbian in question should be pressured to giving men a shot. Or that maybe, a man should just take a shot with them.

This is not a new idea. The idea of the “lesbian who can be turned straight by the right kind of man” haunts queer representation in media. And it’s infected the minds of a lot of straight, cisgender people, who love to tell queer folks that we need to stop making things hard for ourselves, we need to just give the “normal” way a try.

We don’t have any proof that Fred Rogers had sex with men in his life. In fact, many people have responded to this revelation about Rogers by pearl-clutching and emphasizing how much Rogers loved his wife, how faithful to her he must have been. But none of that is relevant when discussing attraction. Rogers described his attraction and orientation in pretty plain terms — halfway between straight and gay, he was attracted to men and women.

Just as a straight virgin who loves to pressure lesbians into dating him doesn’t need experience to know that he is attracted to women, a bisexual, lesbian, or gay person doesn’t need sexual experience to know that they are queer.

The “world without labels” derailment.

This is another dismissal of bisexuality that hides its bigotry behind a smile. “Imagine a world without labels!” this take says, “Imagine a world where no one has to define themselves by who they love! Love is love is love!”

What’s wrong with this take, which looks at first blush to be filled with sparkles and light and the love of equality? Well, the first thing amiss here is that it ignores the deep value that labels bring to the lives of many marginalized people. A lot of us queer people love the shit out of our labels. Finding the label that fits is like coming home to yourself. We don’t want to give that back. Losing the ability to self-identify would mean throwing us back into a world of uncertainty, loneliness, and ineffable pain.

Words exist to divide things up. To point out how X is different from Y. And while that process can be oversimplifying, it is also crucial. Without a label, we are left in the realm of the unfindable. Feelings of attraction, longing, dysphoria are all muted when we cannot express them, and our alienation builds when we can’t find other people who relate to us in similar terms. Words allow us to find community, resources. They help us convey that we are not alone.

But there’s something even more insidious about hoping for a world free from labels. And to grasp that, you need to understand how labels allow the oppressed to describe themselves as oppressed.

A sexual orientation label is not some pointless, categorical thing. It’s not like calling myself a “Little Monster” because I still like Lady Gaga’s music. No, a sexual orientation label allows me to name that I was told, from the moment I was a conscious being, that my impulses, desires, and feelings were abnormal. But all the while I was being told that, I was being folded, sometimes by force, into the realm of the normal. I was expected to be interested in certain kinds of people, and to relate to them in a particular way; it was taken as a given that I’d desire a certain kind of life.

There were no words for anything else. Hell, there were barely any words for the default state of affairs, because naming it would draw too much attention to it. There was nothing but the normal, and any deviant feelings I experienced were a sign that I was wrong or sick. To have words for what I was feeling — bisexuality, gender dysphoria — would be to open up a realm of possibilities, causing the entire infrastructure of the normal to be strained. It can only be truly normal, fully normal, if we don’t even know that an alternative to it exists.

When an oppressed person finds a label that suits them, they are crying out against the grueling, unquestioned requirement of normality that has left them isolated and suffering. When they say, proudly, that they are bisexual and other people are straight, they are making it clear that the world has done wrong by them, and that there are people with more power who are responsible for that wronging.

And so, when we wish for a world without labels, we are saying that we’d prefer the marginalized have no way to make us feel bad about their marginalization. We’d like to see them return to the state where all things are “normal” and nothing else exists.

There will never be a world where everyone is equally “normal” to everyone else, where no one is in the minority, or made to feel strange. I’m sorry if that seems bleak, but it’s true. So long as there are human societies, there will be majority groups who impose unfair expectations on minority groups. And so long as that is the case, those in the minority will desperately need labels.

So please, nice straight people of the world, don’t tell me about how you hope for a world without words like “bisexual”. You may not realize it, but you’re saying that you’d prefer I be unable to identify your foot on my neck.

…

Some valid critiques of Fred Rogers being labeled bisexual.

There are some genuinely sensible reasons to take issue with Fred Rogers being labeled bisexual, and I’d like to acknowledge them.

First, Fred didn’t use the word bisexual for himself. That is a biggie! He said his attraction was in the middle of straight and gay (which is not how most bisexual people would describe their orientation), and he said he was attracted to women and men. We don’t know that he would have ever adopted the label bisexual. Maybe he would have gone with pansexual. Maybe he would have not wanted to label his identity. Maybe he would have gone with queer. We don’t know.

This is often a problem when discussing LGBTQ figures from the past. It’s not completely fair to use today’s terminology for people who existed in a different milieu. At the same time, it’s also unfair to bar modern-day queer people from ever using queer terms for historical figures with whom they share a great deal. That makes it impossible for LGBTQ people to find a sense of cultural continuity, makes it easier for people who hate us to claim that we are some new, perverse moral aberration.

So when I say that Fred Rogers is bisexual, I mean that he felt what many bisexual people feel: an attraction to two or more genders. I mean that he falls under the bisexual umbrella, alongside pansexual people, queer-identified people, and people who don’t like using any of those words. I would be just as happy to hear a pansexual person yelling excitedly that Mr. Rogers was pan.

The second issue is that Fred was not a flawless ally to other queer people. In fact, he pushed one of his friends and colleagues to closet himself. Here’s how Francios Clemmons described Rogers’ response to finding out that Clemmons was gay:

Now I want you to know, Franc, that if you’re gay, it doesn’t matter to me at all. Whatever you say and do is fine with me, but if you’re going to be on the show, as an important member of the Neighborhood, you can’t be ‘out’ as gay.

Clemmons took Rogers’ words to heart, and hid his gay identity throughout the run of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood. This quote, and Clemmons’ resulting marriage to a woman, are used as evidence that Rogers was an oppressive figure, a functionally “straight” man who kept other queer folks in the closet.

But the story does not end there. Fred Rogers went on to regret his treatment of Clemmons, and eventually encouraged him to pursue relationships with men. He came to realize that his take on gayness — “It doesn’t matter to me, but you can’t be out” — was stigmatizing, and cruel. Throughout their friendship, Rogers was someone Clemmons could talk to about his orientation. Rogers also made it a priority to hire many gay people to work on his show.

Ultimately, Rogers was afraid to take a principled stance in favor of queer people (including himself), and that fear caused pain and alienation. I don’t have any interest in excusing that. I don’t think pointing to the prejudice of the times justifies it. I don’t think pointing to the other good things he did counteracts it. He did something that caused massive trauma in a gay man’s life. He avoided the opportunity to defend a group of people he believed he loved.

But I do think Rogers’ own queerness needs to be considered as a factor, when we are weighing his moral failure versus success. He hired many queer people into his staff, he had numerous gay friends to whom he was unflinchingly warm, but imperfectly supportive, and in quiet moments, like the interview with Hirsch, he admitted that he had queer feelings, too. His own queer identity may have played a role in why he was so reticent to take a bold stance in favor of queer people. It doesn’t undo the damage that was done, but it does make him quite a bit different from a homophobic straight person.

Why Fred Rogers’ bisexuality matters.

Ultimately, we cannot know how Fred Rogers would identify himself today, or where he would place himself in modern queer activism. We have only fragments of other people’s memories, a few crucial lines during a recorded interview, and our own appreciation for his kindness and love. He was an imperfect man, but one who did a great deal of good alongside harm.

So why are so many bisexual people latching onto him as a #bicon, when he never used the word for himself, is guilty of homophobia, and is dead? Can’t we do better than that? Of course, today we can. In a world with Janelle Monae and Stephanie Beatriz, do we need Mr. Rogers?

I think we do. Straight people and straight systems of power love to act as though queer people are new, and that therefore we are optional. When we look to the past and see clear, explicit signs of queer identity, attraction, and love, we have to latch onto them, because they provide us with proof that our labels our genuine, our oppression is real, and that we cannot be erased from existence. And figures like Mr. Rogers remind us that queer history was messy and filled with trauma and compromise — that for every out, proud Oscar Wilde-esque historical figure, there were scores of more cowardly queer folks hiding in the wings, whispering only about their desires and never feeling empowered to take a stand.

We don’t know how Fred would identify today. But we know how he explained himself in his lifetime. And that description was bisexual as fuck. And that’s a reminder that bisexual people have always existed, and have always deserved better.