How Commercialization and Assimilation Shook the Queer Community

A retrospective on Daniel Harris’ The Rise and Fall of Gay Culture

I picked up a copy of Daniel Harris’ 1997 book The Rise and Fall of Gay Culture at an estate sale a few summers ago. Nestled on a shelf alongside self-published gay locker room erotica, original edition Beanie Babies, Robert Mapplethorpe photobooks, and dusty mosaic glass knickknacks, the book instantly pulled me into a world that I only got to inhabit with the dullest of proto-queer consciousness.

I learned something completely new about the history of queer culture within the very first page, a fun little factoid combined with analysis from Harris that would forever turn my understanding of my own career on its head: Did you know there was an entire cottage industry of queer-positive self-help books released in the 1970s and 1980s, which were designed to help shame-ridden gay men, bisexuals, and lesbians feel more confident in their queerness, and more comfortable being openly queer?

These “glad-to-be-gay” books, as Harris refers to them, became a mini-phenomenon following the release of George Weinberg’s Society and the Healthy Homosexual in 1972, which introduced many readers to the possibility that a person could be openly gay and thrive, and could seek psychological support to help them more freely live their queerness, not in an attempt to cure themselves of their sexual orientation.

In the years to come, dozens of well-received and profitable self-help books for LGBTQ readers would be released, advising queer people on how to come out to their parents, get plugged into their local community, find local watering holes and cruising spots, ward off stigma-fueled thoughts of suicide, form healthy and supportive partnerships, have reasonably safe and fulfilling sex, and generally lead lives that were more brilliantly, defiantly gay.

As a self-help author who pens books that encourage readers to lead lives that are more brilliantly, defiantly Autistic and transgender, I was moved to learn the work I do is part of such a legacy. Before I started authoring books, I tended to side-eye the self-help genre. It typically offers its despairing readers conventional platitudes that reaffirm society’s dominant values and avoids addressing the societal causes of psychological and emotional struggle. But it turns out that the original LGBTQ self-help books were incredibly political. They normalized queerness, affirmed that gay people were not pathological, and offered encouragement to LGBTQ individuals who wanted to overcome shame and live more vibrantly as themselves.

Harris writes that it was the discovery of Society and the Healthy Homosexual as a teen that put him on the path toward self-acceptance, and led him to become the openly gay, openly political author he was when he penned his own book. (In the acknowledgements of his book, Harris fondly remembers a friend, the journalist Philip Shehadi, who was an outspoken advocate for Palestinian rights, and was mysteriously murdered in his home in Algiers while reporting on the Gulf War).

It is because of this abiding dedication to political analysis that Harris chose to report on how dispiriting he found modern gay culture — it had become too commercialized, too assimilationist, and lost much of its transgressive verve. That’s the underlying purpose behind the book The Rise and Fall of Gay Culture: to contrast the early, fiery defiance of the queer liberation movement with the tamer, more family-friendly, advertiser-courting approach that came to predominate it.

Though this book critiquing “modern” gay culture is older than many of the people who will be reading my review, it’s shocking just how relevant many of Harris’ critiques remain today. Much of the tendency toward assimilation and commercialization that Harris complained about in the nineties has only intensified today, and in his recollections of what earlier, less-respectable gay life was like, he provides an important cultural touchstone for all of us that don’t remember so well.

Chapter by chapter, Harris explains how a move toward widespread acceptance anodized essential areas of queer life: from the art of diva worship, to personals ads, to attitudes toward monogamy and marriage, to the writing of literature and porn. I’d like to review some of Harris’ reflections, chapter by chapter, summarizing what I learned from his book about queer life of the past, and drawing connections to the worrying trends of the present wherever I can.

This book is filled with useful qualitative research, archival analyses, and personal hobby-horses from Harris that are at once prescient and completely unique, and I knew by the time I had finished a chapter that I wanted to share its wisdom with the world. It is my hope that this piece will encourage more queer people to delve into our community’s history by picking up a used copy of Harris’ book, visiting their nearest queer archives (if you’re in Chicago, the Leather Museum & Archives’ library is astoundingly good), and engaging with the thoughts of the past as a way to better understand our present and future.

So without any further throat-clearing, let’s jump in, and take a look at how gay culture rose in prominence and organizing power throughout the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, and then began a decline, in Harris’ view, into rampant consumerism, self-loathing, and conservativism.

Diva Worship

Harris writes that in the middle of the 20th century, gay men revered divas such as Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich, and Judy Garland because of their “hard-bitten careerism” mingled with crushing vulnerability.

These were the icons for the sensitive, othered, and wildly unconventional inner selves that so many queer men during that era had to hide from the outside world. The divas that gay men clung to were themselves outsiders: frequently queer women themselves, gender non-conforming in their independence and drive, a powerful blend of stereotypically “masculine” steeliness and feminine allure that men who had to hide their effeminacy in order to succeed in straight society found incredibly alluring.

It is also because of their experience of being othered and hidden away from society, Harris writes, that so many gay men form an attachment to being cosmopolitan, well-groomed, and consumeristic. We don’t have a biological predisposition toward loving sumptuous interior design, and sucking cock doesn’t make us also salivate over the latest runway fashions; rather, many of us reach for these status symbols and identify with glamorous divas because they set us apart from the mainstream, as we always have been set apart, but in a more showy glamorous way that defies hiding. Harris writes:

“…the preciousness of the aesthete, our love of Japanese screens, Persian carpets, kimonos, capes, MGM stars, and British accents, reflects less the homosexual’s innate affinity for lovely things, for beauty and sensuality, than his profound social discontent, which we attempt to overcome by creating flattering images of ourselves as connoisseurs and epicureans.”

It is in this rush to overcome social discontent, Harris says, that led so many gay men flocked to queer icons like Judy Garland. During the latter stages of her career, when she was openly drunk at most shows and her singing was abysmal, gay men loved Garland shows all the same — because her performances offered a place where they could come together in large numbers to cry, sing, simper, and camp it up. Garland shows were gathering places, and being in the fandom of a major movie diva was a way to signal one’s sexual predilections in a world where open acknowledgement of queerness was dangerous.

The love of divas was a genuine one, because the likes of Crawford, Taylor, Davis, and Garland provided gay men with an outlet to meet one another and to revel in their feminine sides in a dramatic, showy way, to imagine themselves as powerful feminine wits and to have that feminine power recognized by others. In the wounded defiance of the diva, men who had to hide their soft side could find an inner strength.

As the decades wore on and queer liberation began scoring some victories, however, younger gay men’s relationship to divas soured. Once empowering symbols, they became the butt of a joke: younger drag queens imitated the slurring of Garland and the bedroom-eyes of Bette Davis in clownish, mocking ways, no longer empathizing with their anguish or their trapped, butterfly-under-glass position.

Once drag became a commercially successful venture on a mass scale, diva impersonation became just another rabbit a performer could pull out of her hat. References to mid-century movies that had once been deeply infused with meaning became thoughtless memes. Worst of all, according to Harris, this open mockery of divas also became a form of self-mockery, as drag performers came to rely more on the deep pockets of straight audiences who gawked and treated them like a freak show, instead of queer audiences, who saw beauty, affirmation, and power in their feminine displays.

Eventually, Harris writes, newer generations of queer people would come to view camp, effeminacy, and diva worship with distaste, seeking to avoid the social judgement they now associated with such displays, though those very displays had originally existed to spit in the face of a straight society that sneered at them.

Today, we can see the logical extension of Harris’ observations continuing to play out: the drag performers of the current generation still sometimes play being Elizabeth Taylor or Marilyn Monroe, but in over-exaggerated and thinly-drawn ways. More modern figures of fearsome, fragile femininity like Anna Nicole Smith and Amy Winehouse are similarly mocked. And diva worship itself often takes the form of stanning mainstream pop stars, a common commercial practice that cuts across identity, rather than a transgressive act associated with being gay.

I have loved Lady Gaga for a very long time, but choosing to stan her is more like selecting a brand of laundry detergent than it is finding a welcome refuge from the straight gaze. I could just as easily have picked Taylor Swift or Beyonce to hang my attention on.

None of these are women on the downswing of their careers, and as resonant as many of their lyrics might be, they are not “for” outsiders. They are millionaires and billionaires with performances and concert videos airing in Israel to the cheering audiences of the IDF, still not breathing a word of criticism almost two years into the genocide. Judy Garland’s death reportedly helped fuel the passionate fire of the Stonewall Riots; the last time any one of today’s divas got even remotely political, it was to sing at Biden’s inauguration.

The gay diva market has officially been absorbed within the straight commercial stanning machine, and much of its original luster and uniqueness has been erased. This will be a prevailing theme in Harris’ book: the more that LGBTQ people are embraced as regular consumers, the less of our culture we have left for ourselves. But it’s not just how we love actresses and pop stars that has changed — we’ve also shifted in how we find and love each other.

Personal Ads and Romance

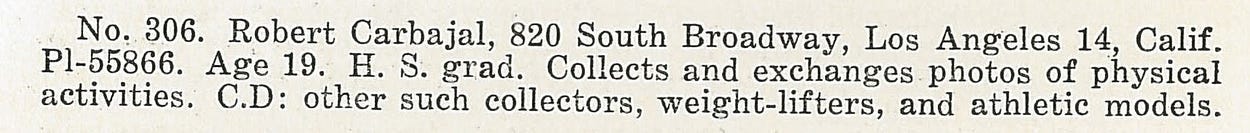

Remote queer courtship has a far longer history than I ever knew about before reading this book. Harris writes that in the 1940s, gay men first began placing personal ads for one another between the pages of the periodical The Hobby Directory.

Originally published by a high school teacher seeking to pair ardent stamp collectors and model makers with potential new friends, queer men flocked to the pages of the directory and all but took it over, slyly labeling themselves “bachelors,” “art patrons,” and “sea-going swabbies” in search of men with whom to share a “true friendship” and go on “adventures.”

It was common for entries in the directory to advertise a winking interest in weight lifting, modeling, or portraiture, as in this example that I found online:

In the research for his book, Harris read through archival entries of The Hobby Directory and similar magazines from that era intensively, performing a qualitative analysis on the contents of men’s personals ads. He reports that generally, men in these early days used vague, yet knowing language to covertly signal queerness. They also wrote openly about their loneliness and desperation, many of them stating that they lived in the countryside and were happy to meet with just about anyone within hundreds of miles who might be queer like them.

Early personal ads didn’t generally describe the applicant’s physical qualities or personality (lest the author be exposed), nor did they outline many of his specific desires for a partner. Instead, applicants were hoping merely to connect with someone, anyone, with whom they could be themselves authentically. Harris quotes these example entries:

Will welcome all letters from anyone who can write.

Will respond to males within a radius of 100 miles.

Would like to hear from anyone, anywhere.

Wishes correspondence with other gay men.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the nature of gay personal ads slowly began to shift. More openly queer periodicals began coming out, and applicants could openly state that they were seeking “gay bachelors” or try to sell “Mae-West enemas.”

Publications like Cruise News & World Report and The Advocate’s Trader Dick’s provided an outlet for raunchy, frank discussions of sex, and personal ads became more direct, as well as more demanding. At last gay men had the freedom to be selective, seeking “Daddies & Daddies Boys,” “Pig Sex,” “Relationships”, and showing early signs of the body fascism and anti-Blackness that still appears regularly on dating apps.

Far from longing as they had in the 1940s and 1950s to find anyone who was gay, queer men in the 1970s and into the 1980s chased the fantasy of Mr. Right: the man who had absolutely everything the applicant desired. Harris says that these later-stage personal ads tend to emphasize the importance of attractiveness, long-term commitment, and wealth on a level not seen in queer personal ads before.

No longer seeking connection and the formation of community bonds, many dating applicants now wanted to find the ideal partner with whom to settle down and combine finances. Around this period, dating ad writers also began describing themselves, slotting into identity categories such as “hairy,” “rugged,” “Daddy,” “slave,” and so on.

Gay men were no longer in hiding to the degree they’d been before, and with their increased exposure and normalization, they could begin taking one another for granted, just as straight people on the dating market do. Less conventional, community-oriented relationship structures were gradually replaced with talk of marriage and what Harris calls the “heterosexualization” of gay partnership.

This trend was only intensified by the arrival of HIV, which pushed many queer men into sexually exclusive relationships. Harris shows that many gay personal ads of the 1980s suddenly began to broadcast a desire to form a “cozy love nest” or secluded romantic safe space, locked away from the world of illness and loss. The open longing of the 1940s and the raunch of the 1970s were both swiftly replaced with desire for a womblike escape into monogamy. Unfortunately, this resulted in some gay men detaching from more communal, organized queer life, and into a more nuclear, individualized existence.

We certainly see the legacy of many of these men in the Pete Buttigiegs of the world: assimilationist gays who present to the world as married, monogamous family men who resemble their straight counterparts as much as humanly possible. There’s nothing wrong with any LGBTQ person pursuing marriage, parenthood, or exclusivity if they want to, of course. But when only the most respectable and conventional among us serve as the face of queerness on the political stage, those of us who are kinky, wild, slutty, and weird get left behind.

I can only guess at what Harris would write today about queer dating on the likes of Scruff, Tinder, Lex, and Grindr. In general, the pursuit of perfection has only worsened: sex seekers on the apps can outline their exact physical specifications and distance requirements and summon a hookup as dispassionately as ordering Grubhub.

As someone who has done exactly that many times, I’m in no position to judge. It’s wonderful for LGBTQ people to be able to find one another wherever we go; I’m often comforted by opening up Grindr and realizing that people like me are mere feet away. But it does potentially inject courtship with a chilling dehumanization: partners are interchangeable commodities to be found, used, and replaced at will, I think Harris would point out.

And even on less sex-focused apps like Lex, the fixation on individual categorization and expectation of perfection in a partner are still quite evident. Everyone is a plant-daddy-neuro-spicy-goblin-bottom looking for the flawlessly educated, generous dommy-mommy top who will intuit their precise desires and do all the work of making sex happen for them.

I’ve had a lot of great experiences from cruising on the apps. I find it far more useful than navigating the nonverbal signals and flexible social norms of in-person cruising. At the same time, the proliferation of Grindr, Sniffies, Scruff, Feeld, and all the rest have slowly siphoned resources away from treasured queer community spaces like gay bars. Without shared gathering places, we lose an important ability to connect and build social infrastructure and organizing power for ourselves.

When having sex and dating becomes as effortless for us as it is for straight people on Tinder, LGBTQ folks lose an important bond that transcends attraction and demographics. I don’t envy the men using hobbyist magazines in the 40’s and 50’s to encounter literally any queer person, but they did at least recognize how much we all need one another, regardless of how hot or wealthy we may or may not be.

I think that with experience, many queer people of today do come to realize that, too. But sometimes when I encounter a lifelong closeted or “down low” guy on the apps who is seeking his ideal, hairless, bubble-butted 5'6'’ transgender sissy to briefly fuck and then push out of his hotel room, I do wonder if we are better off than when we had to visit bars and actively be around a lot of one another in order to have sex.

Publishing

In multiple chapters, Harris describes how queer magazine and book publishing shifted as LGBTQ identities became more mainstream and were more widely marketed to — and often, this change came at the expense of openly queer defiance and in favor of lining major corporation’s pockets.

In the 1960s, Harris writes, queer publishing was quite underground, and often erotic: magazines like Trim presented photos of buff, handsome young men as a study in athleticism, and After Dark included arts columns and reviews of stage plays alongside photospreads of hulking biceps and stiff hard-ons pressing against the inside of dancer’s leotards.

Male pornography was still quite rare to find during the publication’s heyday, so After Dark’s luridness and its subtle, yet recognizable signally of queerness led it to amass over 350,000 readers per year. (As someone whose “best-seller” has sold about 250,000 books in three years, let me tell you: those are big numbers! Bigger than anything we see in published media today.)

These magazines rarely mentioned queer topics outright, but like the hobbyist personals of decades prior, any gay male reader could find a home within its pages if they were in the know. And many, many of them were. These were often the kinds of LGBTQ community spaces that had to form in the middle of the 20th century: policed with a glance and a wink, the Judy Garland concerts and arts columns where queer people could find and celebrate one another were often hidden in plain sight.

Over time though, as the counter-cultural movements of the 60s normalized sex, more explicit porn mags proliferated, queerness was more openly acknowledged in the press, and magazines like After Dark suffered. Gay men didn’t have to find their masturbatory smut in artsy, alternative magazines that could be passed off as something other than porn, they could just go and buy full-frontal nude photographs outright. Meanwhile, more mainstream gay magazines like Out and 10 Percent began to emerge and discuss LGBT issues with more frankness — and less skeeze.

Unfortunately, according to Harris, once queer magazines were no longer niche masturbatory aids covertly masquerading as arts magazines and instead were taken seriously as legitimate forms of publishing, that meant attention began to arrive from advertisers. The Wall Street Journal declared gay men the “dream market” for advertisers, because gay couples represented two male incomes without the expenses of kids. The pages were suddenly filled with marketing materials for vodka, cognac, cigarettes, travel packages, leather couches, and luxury sweaters.

These advertiser bucks also brought the pressures of the corporate world: the magazines than ran them had to cut their nude photospreads, eliminate their personal ads, and cease running articles on the art of cruising or advice columns on how to insert butt plugs. Instead, articles in gay magazines of this era began to frame financial success as the ultimate proof of gay people’s social acceptance. Rather than aspiring to develop a political power that could shift the social norms and make public life more comfortable for a variety of queer people, sanitized magazines celebrated the first queer CEOs and profiled high-achieving, quietly partnered gay philanthropists and advertising executives.

Harris writes:

“The new glossies seem to suggest that the secret to ending oppression lies not in the courtrooms and the legislatures, but in our wallets and stock portfolios, in the massive quantities of disposable income with which footloose-and-fancy-free gay men can buy their own manumission.”

These publications were a far cry from the unquestionably political, pro-gay self-help books that had helped Harris discover himself and empowered countless queer men like him to pursue fulfilling, unconventional queer lives. The magazines of the 1980s and 90s instead focused on individualism. Gay men, he says, were no longer encouraged to feel fine as they were, but rather to aspire to something better: buying and wearing the signifiers of their acceptance, always working to rise up the corporate ladder.

Once aesthete collectors whose treasured antiques broadcasted their own difference, gay men were now being encouraged to become consumers in order to telegraph their assimilation: they were to dress in slick, pressed suits just like any other man would, aspire to sit in boardrooms and quaff fine liquors that only the most achieved and respectable of men could. Then, and only then, would they know that they’d successfully overcome their proximal status — no matter how many other queer people were left behind.

Though magazines like Out, 10 Percent, and Genre catered themselves to a more mainstream audience, they never reached the level of success of bawdier, seedier magazines like After Dark. Their combined readership was only about half of After Dark’s readership — and Harris explains this as a logical consequence of assimilation. There was simply nothing special about these publications, nothing that spoke to what queer people needed. It was just the same corporate boilerplate you can still find in GQ.

The more that LGBTQ people position ourselves as indistinguishable from straights, the less that we get to enjoy spaces and creations that are entirely our own. The more that we aspire to personal success in the conventional, heterosexual sense of the term, the less pride we can feel in what makes us unique. When queer publications sanitize themselves in pursuit of greater advertiser revenue, they are spelling their own long-term doom; queer people who seek the approval of the straight world rather than aiming to disrupt it will wash all signs of their culture away until there is nothing left.

Many of Harris’ observations about the deeper cultural price of assimilation could easily be made about queer community spaces and media today. Like the gay magazines of the 1980s, our Pride parades and festivals today have become overstuffed with advertisements for alcohol companies, airlines, banks, and skincare lines, the actual festivities censored to create a more “family friendly” atmosphere. And as society takes a reactionary, homophobic turn, corporate sponsors pull out, advertiser revenue dries up, and queer people are reminded that we were only as a revenue source.

And as much as we have seen major steps forward in terms of queer depictions in media over the past few decades, even the tamest and sweetest of gay romance stories still get insulted as pornographic and “grooming” material. The digital platforms that once placed us front and center in their pride displays now openly censor us, and revise their moderation policies so that users can accuse us of mental illness. Like the publishers of Harris’ era, the corporations that control our access to information today have decided the reality of queer life is not safe for advertisers, and therefore might as well not exist.

There’s no amount of tameness that will placate those that hate us, or even those that simply see us as a way to make a buck. We are still being expected to wash every last drop of ourselves away.

The final section of Harris’ book that I’d like to talk about today is another one in which economic changes has led to a massive artistic loss — the world of queer porn.

Porn

Some of the first forms of filmed gay pornography were the “smokers,” silent shorts from the 1950s and 60s depicting nude young men swimming in hidden watering holes, and buff Adonises lifting weights outdoors while blushing admirers watch from afar. These films were difficult to produce, as filmmaking equipment was prohibitively expensive, and were generally only viewed at underground pornography theaters and during late-night showings long after movie houses had shut down for the evening. They often avoided nudity outright, as on-screen depictions were still illegal.

I’ve seen some of these films myself, playing on the TV screens at the local gay bar Big Chicks, so I was somewhat familiar when Harris mentioned them. They’re cartoonish, with a charming naivete about them that feels like a kid’s earliest sexual fantasies. But what I had no idea about were the incredibly artistic, sensual, downright psychedelic takes on gay porn that spread in the 1970s, as pornography laws loosened and camera equipment became more accessible to members of the public.

Gay porn of the 1970s was far more layered and had more literary aspirations than most porn we think of today. Lengthy plotlines stitched together the moments between sensual love-making scenes, helping filmmakers to justify to potential censors that their movies were legitimate art. As a result, 1970s porn films are often languid-feeling and dreamlike, with long passages of characters wandering around or narrating their lives drawing out the viewer’s arousal and keeping them on the edge for hours.

Because recording live audio on-set and then synching it with video was still incredibly difficult and expensive to do at this time, most gay porn of the 1970s did not have dialogue, nor did it have realistic sexual sounds. Instead, an actor’s dubbed voice-over describes their psychological state and desires, offering moans and guttural rumblings of pleasure in a more abstract or symbolic sense. Low-fi music helps to set the tone, and the lighting is usually dim and impressionistic. Performers stand like mannequins at one another’s sides, or pose in front of mirrors, regarding themselves for whole minutes. Their actions breathe sex, but it’s otherworldly, and not rote.

Sex scenes are shot in a deliberately confusing, kaleidoscopic way, Harris says, to help blur the space between the performers’ bodies, and to represent the sensation of joining into one copulating unit. Legs, arms, genitals, tufts of hair, and muscles appear in numerous short cuts and the movement of them is undulating, vague.

Harris says these films are mainly intended to capture the sensation one feels when wrapped up in the action of having sex, not depict how sex actually looks to another person from the outside. He also explains that since most of these movies were shown at gay men’s pornography theaters, they were meant to serve as the backdrop while men fondled and cruised one another. They were not the focal point, they created an overall atmosphere of desire and escape.

Peter Berlin’s 1974 film, That Boy (which I’ve written about before) offered me a glimpse into just how different gay porn used to be, and what we’ve lost artistically from the move toward mass-produced consumer cameras and video-playing devices. Unlike Harris, I didn’t find Berlin’s dreamy cinematography and long sequences at all boring. To me they were transportive, and evocative of real emotion, both stirring and intellectually stimulating on a level very few porn videos have ever been for me.

The Asexual Fetishist

It’s 9:30 am on a Monday, my regularly-scheduled time for a workout. Like always, I pad across the floor of the living room, roll out the yoga mat, arrange the dumbbells, and flip open my laptop to find a follow-along strength training video on YouTube.

Harris says that once consumers got their hands on VCRs, the entire landscape of pornography changed: viewers could fast-forward past long passages of plot and get right to the smut, replaying their favorite money shots over and over again. Porn producers adapted by creating large compilations of more slapped-together scenes, without much thought of aesthetics or plot.

As filming equipment improved in quality, porn became more focused on capturing the real physical appearance of sex. Rather than inviting the viewer into the minds and bodies of the people copulating, porn actors were positioned like anatomical drawings and put upon display.

Everyday people with regular, varied bodies were replaced with muscle-bound models without an ounce of body fat. A variety of visually pleasing yet physically uncomfortable sexual positions were adopted, the lights turned up to full blast, close-up shots capturing every dribble of saliva and spray of semen. Orgasm was no longer an internal, psychological experience, it was a reason to pause and reposition the shot.

Though in theory one might expect more realistic filming styles to result in work that felt more intimate, in actuality the opposite happened: porn moved away from art, and began treating its subjects more like meat. (That can be plenty fun too, but as someone who is obsessed with headspaces, I’d much rather get a sense of what it feels like to be the meat).

What Harris finds the most dismaying about all these changes is that porn quickly became aspirational rather than psychologically realist. Men now masturbated to it, rather than having it in the background while they had sex with somebody else. Slowly, it trained them to adopt new expectations of how sex ought to play out.

“Pornography shows us how sex should look,” Harris writes, “not how it really looks. Its effect is prescriptive and judgmental.”

The same can certainly be said of the porn of today, which trains young men to expect flawless bodies engaging in prep-free anal, effortless deepthroating, and kissing with lots of performative (if unpleasurable) wiggling of tongue. Performers move themselves through the stations of acceptable sex: one position right after the other, all perfection, no passion.

But the porn of the past used to be almost stream-of-consciousness, and beautifully descriptive of the trippy, melting sensation that is getting swept away in good sex. And we still could return to it, if our focus was to use our existing creative tools to produce expressive art, rather than to seek mass-market commercial success.

The one upside to the spread of OnlyFans and JustForFans that Harris might see, if you asked him, is that it allows porn creators to craft their own unique vision, and cater to audiences with highly specific tastes. I’m reminded of Cam Damage’s artfully bloody, creepy, and yet sensitive industrial-music-tinged pornographic videos, in which he depicts himself as a black-eyed, possessed beast wrapped in rubber.

On his Patreon, Cam says he creates “emotions, sensations, and reactions” with his films, which sounds appropriately similar to the psychedelic, emotive goals of the porn of the 1970s. The porn studio he co-founded, Collective Corruption, releases carefully produced erotic films about sexy hauntings and inky latex demons writhing atop one another that are similarly artistic, and a frequent collaborator of his, Reflective Desire, puts out some of the most inventive and visually pleasing latex porn you could imagine. Another porn studio that I love, House of Hedge makes high-concept, trippy erotic films about cult indoctrinations and sexy mind control worms that I think many of the porn makers of the 1970s would have understood intuitively.

There is a future for sensual, imaginative, distinctly queer porn. But like so much of what makes queer culture special, it has needed to germinate in quite corners and independent niches where censorship and corporate control can’t quite get its tendrils.

There are so many other fascinating sections in Harris’ book that I didn’t quite have time for, about dramatic shifts in how LGBTQ people approached body image, kink, kitsch, and even underwear across the generations. If you can find yourself a copy (and there are used copies online at an affordable price), I highly recommend picking up this piece of our history.

I was generally astounded by how many of the changes that Harris warned about in 1997 remain completely relevant today. There is truly no queer struggle under the sun that is new, it seems, and our community has been having many of the same discussions about the cost of commercialization and the self-defeating nature of respectability politics for far longer than many of us have been alive.

When I can recognize my own life and concerns within the queer generations of the past, I feel more firmly grounded within myself, and more placed within a larger culture that recognizes me, and can care for me (and which I should also take care to maintain). Knowing more about what our community has faced in the past also helps me to feel prepared for today’s present threats, and the uncertainty of our future.

As marginalized people, our histories are constantly at the risk of erasure, but we cannot move forward if we don’t understand where we have come from and all the wisdom that our liberation has already been built on top of.

Harris’ book warns repeatedly of the risks of losing what makes us distinct and sets us apart, calls us to remember a time when simply seeing another gay person or reading their words was precious beyond all measure, and asks us not to lose sight of ourselves. I think he’d be pleased to know that a quarter of a century after the publication of his book, reading it has helped me to briefly put aside the distractions of online discourse, clout-farming, and disempowering panic, and remember what we are really here for: to defy, shock, give pleasure, find connection, and survive.

The section on gay personals reminded me of some work I did in undergrad digitizing letters from readers of ONE Magazine, which ran in the 50s and 60s. Many letters came from socially and geographically isolated gay men looking for all kinds of connection and company.

ONE was a very early gay publication in the tradition of the Mattachine Society; it was more an ancestor of Out than After Dark. To me, the letters represent an interesting transitional phase between the coded Hobby Directory ads and the more forthright personals of the 70s and beyond. It was a very touching experience for me as a half-closeted young person to spend time with these letters. You can see some of them here, mixed in with other archival papers–you'll have to dig, but the digging is the fun part: https://digitallibrary.usc.edu/CS.aspx?VP3=DamView&VBID=2A3BXZLZI2PWR&SMLS=1&q=ONE+magazine&RW=1512&RH=773#/DamView&VBID=2A3BXZLZI24KU&PN=1&WS=SearchResults

Thanks for the fantastic article. I'm looking forward to reading this book!

thank you for this, i'll definitely be trying to get my hands on a copy. i realized two (three?) things while reading this:

1. my sense of dysphoria is not alleviated by crossing or dismissing the binary but would be alleviated by a sense of community and embraced difference like this. in most "queer" spaces i go to i feel like i don't fit in at best and i feel like i'm in a zoo at worst. (especially because i still take covid precautions) it's very difficult to find people that understand how deep the rabbit hole of queerness goes.

2. i think some of the supposed "media literacy crisis" was birthed out of the diminishing of the arts as unclear communications. between advertisers getting their hands on things, then trying to water them down, queer people had their art ripped from them as a core part of identity. i don't know how to put this into words really well but the idea that we lost our subtleties in favor of bluntness and objectification means we have lost our ability to understand deeper meaning and things that aren't being outright expressed to us.