How Do I Cope with Anti-Autistic Bias?

Autistic Advice #11: Research shows most people dislike Autistics within moments of meeting them. Is there any hope of us finding connection?

Originally published to Medium on August 15, 2023.

Welcome back to Autistic Advice, a semi-regular advice column where I respond to reader questions about neurodiversity, accessibility, disability justice, and self-advocacy from my perspective as an Autistic psychologist. You can submit questions or suggest future entries in the series via my Tumblr ask box, linked here.

Today’s question comes from Tumblr user localpussyboy, who is concerned by the research showing that non-Autistic people have a reflexive dislike of Autistics, even (or especially) when we are trying to mask our Autistic traits:

Localpussyboy (what a joy to get to write that in a column), I so relate to the concerns you are describing. I have often been preoccupied with worries that the people I meet won’t appreciate the real me, they’ll only see the ways in which my Autistic traits and mannerisms mark me as the “other” — and that no matter how hard I strive to speak the language of the neuro-conforming, I’ll have lost people’s interest before I even try.

If you’re asking this question, you’ve probably read about the research showing that non-Autistic people instinctively judge Autistics as unlikable within an instant of meeting them. Here’s a passage on that research from page 185 of my book, Unmasking Autism:

Sasson and colleagues (2017) found that neurotypical people quickly and subconsciously identify that a stranger is Autistic, often within milliseconds of meeting them. They don’t realize that they’ve identified the person as Autistic though; they just think the person is weird.

Participants in the study were less interested in engaging in conversation with Autistic people and liked them less than on-Autistics, all based on a brief moment of social data. It’s also important to point out that the Autistic people in this study did not do anything “wrong”; their behavior was perfectly socially appropriate, as was the content of their speech. Though they tried their damndest to present as neurotypical, their performance had some key tells, and was just slightly “off,” and they were disliked because of it.

Encountering this research has proven dispiriting for a great many readers. A clip of this passage from the audiobook has gone viral on TikTok, with thousands of crestfallen Autistic people broadcasting their reactions, or writing in comments that though they have worked hard to follow social rules and make themselves likeable, they usually get a chilly, disinterested response anyway.

“They knew,” shared TikTok user Katie Mac. “The kids knew and I was instantly othered. Childhood explained.”

“If you’re Autistic and chronically unliked, it’s them, not you,” Tormentedsoup333 added. “Show yourself some grace.”

The resounding response Autistic people have shared to this clip is one of despair. I think for most of us who attempt to mask our disability, there is the belief that if we’re not fitting in, we must be performing neurotypicality wrong, that if we could only study other people’s postures and practice making small talk just a little bit more, we could master it, and finally gain full access to the neuro-conforming world.

But the work of Sasson and colleagues, as well as several other psychologists, suggests that our problem isn’t a lack of trying hard enough to blend in. We get punished for being different, and for betraying that we’re trying to fit in at all.

Several Autistic people have likened this research to the concept in robotics of the Uncanny Valley, a theory stating that when a robot becomes highly humanlike but not quite humanlike enough to pass as a living thing, people will find it terrifying, in much the same way they’d fear a scary doll or a corpse. This analogy implies that neuro-conforming people see us Autistics as essentially less than human, and our careful attempts at social niceties as but a chilling imitation of the real thing.

This idea is further supported by the research of Leander and colleagues, originally published in 2012, which finds that when a stranger tries to mirror another person’s mannerisms too much, or in a situation where friendly body-mirroring is not desired, it can literally give the observer bodily chills.

For Autistics, ableist bias is painful and isolating, and there can be a real cost to attempting to live up to neuro-conforming standards. But don’t lose hope, Localpussyboy! There are a great many reasons to believe that by unmasking, soothing our social anxiety, and self-disclosing our Autism, Autistic people can forge lasting friendships, and be likeable to other people exactly as we are.

…

Conrad is an Autistic man who used to be involved in the pick-up artist movement. Growing up he was very lonely, and socially disliked. So in his twenties, he says he learned to imitate the hyper-confident men he saw as desirable “Chads”, but did so in a way that really put a damper on his romantic and social prospects.

“I tried to reduce being attractive and well-connected as a man to a series of attributes I needed to have. Women like men that are are muscular, so I will become muscular. Men who do well in business have a firm handshake, so I must have a firm handshake. I need expensive shoes, I need to open doors for women, and when that didn’t add up to me becoming a man people liked, I was very angry about that.”

Conrad describes this thinking as a kind of covert contract, an unspoken conditional agreement with the rest of the world. It was also a form of masking, hiding his shy Autistic self behind a hypermasculine ideal. There were many problems with Conrad’s approach — the misogyny of the pick-up movement being a huge part of it — but another major issue was just how detached this thinking made him from other people, and himself.

“I behaved as a confident man would, but acting in that way did not make me more confident,” he explains. “I was stiff. I was a dick to people. I am more confident now when I’m being vulnerable with people, just humbly being myself.”

A few years ago, Conrad was in a car accident that required intensive spinal surgery. During his recovery, he had to move away from an expensive East Coast city into his sister’s apartment in Kentucky. He uses a cane. He works part-time from home but spends a lot of time outside. He’s not a chiseled Chad, and he no longer tries to grow his “body count.”

Conrad’s best friend is a sixty-five year old retiree; they like going fishing together. Conrad goes to support groups, and posts actively on the ExRedPill subreddit, to encourage other men to abandon the toxic ideals that he once worshipped. He feels more connected now, he says, and more at peace, than when he was trying to make people like him by masking as the ideal type of guy.

Most Autistic people don’t join misogynistic hate movements, of course, but many of us do get seduced and pressured into performing neurotypical ideals in our own self-defeating ways.

Like Conrad, I leaned into a superficial gendered role when I was young and didn’t know how to relate to anybody. I told myself I could not possibly be a friendless ‘loser’ if I was an attractive girl. Experience proved this belief untrue, as I had no friends throughout my image-obsessed, eating disordered early 20s. My superficiality and the narrow rules that I let guide my life only made it impossible for me to know or be known by anybody.

Even after I left all that behind, I still tried studying social norms and professional codes of conduct so that I could imitate them. I was frosty, distant, and judgmental. I was so afraid of being seen as a freak that other people could sense my reflexive mistrust of them, and so they kept their distance. My behavior was highly practiced, my self highly walled, and in retrospect it was no wonder I couldn’t make friends. But once I came out about as transgender and Autistic, and became far more vulnerable about a lot of tough life experiences, caring people started flocking to me.

Numerous Autistic people responded to the Sasson & colleagues clip by throwing their hands up and asking what the the point of masking as non-Autistic even is, given that even the most appropriate, well-behaved Autistic in the study still was viewed as unnamably weird. I think that is exactly the point! Masking doesn’t work nearly as well as we think it does — all its discomfort and falseness is written into bodies.

In numerous cases, masking is actually yet another tool of our oppression: rather than allowing us to pass through the world as neurotypical, it restricts us to an even narrower realm of expression than non-Autistics get to enjoy. When we’re masking, we might believe we’ve unlocked the guidebook to seeming normal and likeable, but actually, we’ve just located the muzzle that was already on our mouths.

There are times when a person must mask for their own safety. Black and brown Autistics use masking to protect themselves from violent white supremacy and police killings. Autistics interfacing with the medical or psychiatric system often have to mask to be treated with respect. It’s perilous to be openly Autistic while we are at work.

Sometimes, masking is necessary. But the fact that it is necessary does not make it good — and the fact masking may bring us some short-term relief doesn’t mean it’s compatible with any of us leading an actually liberated life. To get free, we must escape the social conditions that demand that we mask, as often and as fully as we can.

When it comes to making friends, collaborating, or meeting new people within an even playing field, masking puts many of us at a sharp disadvantage — but by being a little bit more openly freaky and nonconforming, we may discover that the right people actually like us more.

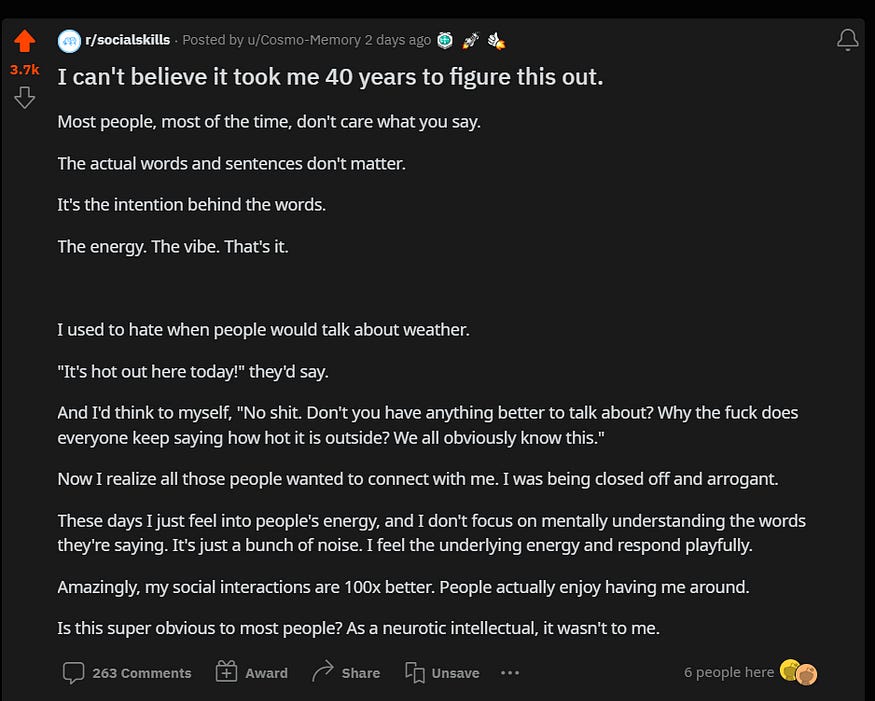

Take a look at this fascinating observation about communication and social “energy”, courtesy of the Social Skills subreddit:

Like the Autistic people in Sasson’s research, and like Conrad and the OP of this Reddit post, I used to communicate by attending to content, not energy. I would practice conversations in the mirror, and learn conversational scripts from TV shows like Hannibal and Mad Men (not the best training base, I know). If somebody asked me a question about how my day was going, or what my favorite book was, I thought really long and hard about what the optimal answer was, and how to translate that answer into something pleasing or socially acceptable.

Everything I did and said was meticulously gamed out. And I failed at socializing. Because what most people picked up on was the gaming. They got a calculated, distant energy from me, and that made them wary. People could sense that I was uncomfortable, and they didn’t want to bother me or intrude, and so they gave me a wide berth.

I know that my hyper-analytic, sarcastic self will never appeal to everyone, and in contentious situations, I’m quite comfortable being disliked. But in order to bond with the people I actually might like, I had to learn to relax enough to be present and receptive to other people’s energies.

Lately, I don’t try to relate to other people by obsessing over my verbal strategy, but by relaxing my energy. Even this is difficult — faking a friendly or at-ease demeanor will also read as calculated, and create a palpable distance. Instead, I reduce my actual social anxiety as needed by breathing deeply, staying off stimulants, and fidgeting with a grounding item such as a bumpy rock or the sharp edge of a piece of jewelry. I clear my head as best I can. I pin my focus on something interesting that is happening outside of me, so that I can stop obsessing over how I come across.

When I feel uncomfortable or stressed within a social space, I try removing whatever sensory input and stressors I can — by wearing headphones, say, or by stepping away to take a break. I try not to decode any hidden messages another person might be giving off. Instead, I turn my attention toward appreciating the shared experience, accepting any positive energy that a person gives me, and giving off whatever positive energy I am actually feeling in return.

This doesn’t always work, of course. I have plenty of neuroses and when life stress has me down, I have to remind myself not to run a constant mental loop of reasons why I’m a social failure. But as a good friend once told me, “the less you try, the more you you,” and I do find that when I am able to calm my mind and just exist in the world with a mellow energy, people receive it, and return it.

This isn’t masking, it’s finally letting myself be without a filter or assuming the worst of others.

Around this time last year, I got homophobically street harassed by two young women living down my block. I slunk around the neighborhood with a protective posture for some time after that. Being mistrustful was sensible, but it also made my social experience worse. I needed my partner to point out to me that most people I walked past were smiling or looking at me in a positive way, if they bothered to react to me at all. Slowly, I started returning gazes and smiles again.

This week a middle-aged woman strolled past me walking her dogs. I was wearing iridescent sandals, bright green short-shorts, and a crop top. I steeled myself for some kind of negative reaction, but then told myself to just relax, enjoy the sunshine, and give her a nod.

“Excuse me,” the woman said gently. “I don’t mean to offend you, but you look like the Barbie movie.”

My eyes went wide. She thought my outfit made me look Ryan Gosling's Ken? “That is a great compliment!” I squealed back.

“I want you in my dollhouse!” she said with a laugh.

It really made my day. The next time I saw her, she was without her dogs. I asked, “Where are your dogs?” and she told me they were inside. It was a inane question, the kind of thing the old me would have avoided saying for fear of being annoying. But I finally understand that the text of what I say doesn’t really matter in these situations. What matters is the energy. My energy said I remember you, I remember your dogs, I like seeing you both, hello!

I didn’t have to plan out what I wanted to say to convey that energy. I just had to open my mouth and let what was already there emerge.

Localpussyboy, I don’t know if you’re like me, but for years I loathed small talk. It all seemed so pointless. I couldn’t understand why people found sharing what time of day it was or what they’d had for dinner remotely fascinating. But one day it dawned on me that a conversation is not about the exchange of information. It’s more like two birds chirping at one another from across the trees. I am here, are you with me? Yes, I am here, I am here with you. How wonderful to be here!

Most conversations don’t have a real goal or a subject they must stick to. A conversation is about you and your conversation partner holding attention together, and finding something, anything really, to direct that attention toward. You can bring up almost whatever weird subject you want when you’re chatting with people, as long as your energy is open. I’ve found I can be a lot more fucking weird and morbid with strangers than I ever thought was possible, once I tried being genuine about it.

Of course, I am not for everybody, and I strictly avoid pretending to agree with a statement I disagree with or to enjoy an activity I don’t like. By being unmasked, I am guaranteed to be off-putting to some people, but it’s really not as many I expected. The same thing has proven true about being transgender and gay. Though I have good reasons to fear that other people will hate me, my instincts for determining who that’s gonna be are actually pretty terrible. Trauma makes us see threat everywhere.

Localpussyboy, we began this article by considering Sasson & colleagues’ research showing that Autistics are instinctively disliked. But here’s the thing. That research only holds for people who do not know they are interacting with an Autistic.

Additional research conducted by Sasson and Morrison in 2019 found that when people know they are interacting with an Autistic person, their dislike completely drops away! Here’s another passage from my book:

Sasson’s research found that when participants were told they were interacting with an Autistic person, their biases against us disappeared. Suddenly they liked their slightly awkward conversation partner, and expressed interest in getting to know them…

Follow-up research by Sasson and Morrison confirmed that when neurotypical people know that they’re meeting an Autistic person, first impressions of them are far more positive, and after the interaction neurotypicals express more interest in learning about Autism.

It turns out that finding out the reason why an Autistic person seems ever-so-slightly “off” relieves neurotypicals’ uneasy, Uncanny Valley feeling, and it opens them up to new ways of relating to other people. It also opens them up to the idea that there are many different ways to exist in the social world.

Another Autistic woman that I interviewed for my book named Kaitlin told me she’s disclosed her Autism to her sorority sister, Chantal. Chantal is a life-of-the-party type. She used to think Kaitlin was a bummer for standing off to the side at social gatherings, staring into her drink. But upon learning that Kaitlin has a disability that makes socializing difficult, Chantal’s whole demeanor changed.

“[Cantal] introduces me to all these people at parties now and tells us both what we have in common so I know what to talk to them about. Or in a conversation she’ll notice I can’t keep up and she’ll loop me in. Oh that’s fascinating. Kaitlin, what do you think?” These gestures have helped keep Kaitlin included.

Self-disclosing as Autistic can be risky, especially in professional or institutional settings.Any time that you are in a position of reduced power, revealing that you belong to a stigmatized group can be dangerous for you. But when it comes to meeting new people and teaching people how to be a good friend to you, revealing your disability is one strategy among many that you can use to your advantage.

Moving through the world as an Autistic person is very difficult, Localpussyboy, and for reasons that are completely not your fault. There is nothing inherently wrong with masking, experiencing social anxiety, or otherwise keeping your guard up. These reactions have formed due to real-life experiences, and at times listening to our worst fears helps protect us — especially when we lack the power or freedom of movement to advocate for ourselves.

But as we grow in our confidence as Autistic people, and develop more power as members of a vibrant, vocal self-advocacy community, our ability to drop these protections can increase. You don’t have to fear every person hating you for being Autistic. The fact that some people will always dislike your mask is in fact freeing — it absolves you of the responsibility to put on that painful act all the time. There is a quiet, defiant courage in being disliked.

But there is also real love and appreciation to be found for us in the world, too. By openly being ourselves, we do risk being marked as an outsider — but we also offer all the neuro-conforming people around us a door out of the narrow standards and harsh social judgements that have also imprisoned them. When we are safe to, we can be a beacon of liberating authenticity. And that is actually very easy for a new person to like.