If you’ve been following me on social media, you might be aware of the complicated and painful medical mystery I have been living out for the last couple of weeks. But for the sake of getting the narrative down, titillating all of my readers who have a keen interest in the workings and failings of the body, and providing an update on what’s next for me, I’m going to outline the entirety of the Hand Saga right here.

At the end of the piece I will explain a little bit about where I am currently at, functioning-wise and in my course of treatment, and what you can expect from my future writings in the next couple of weeks (and most likely, months) as I continue to sort this issue out.

Everything that is written here was initially composed using voice-to-text, particularly the Google voice-to-text function on my Pixel 4a (which seems to do a far better job of interpreting my speech and including punctuation and capitalization than any other voice transcription app I’ve tried so far — send me your recommendations if you use this kind of technology a lot!). After drafting the piece in voice, I edited all of it manually, but if you notice any differences in the flow of my writing or glaring errors, it’s because I am learning to do my work in a completely new way.

My hope is that I will be able to hone my craft further by approaching it from this new angle, and that it makes me a stronger communicator (and a more accessible one) in the long run. Unfortunately, it also requires that I lean on the reader’s patience.

(As you will soon be able to tell, switching to a new input method hasn't made me any shorter-winded.)

Anyway, let’s dive into the Hand Saga.

Thursday, January 9th

I woke up with a pain in the meat of my left thumb.

At first, the ache resembled one I’ve had a few times before in both of my hands, typically after a vigorous session of chest or shoulder presses. I have always had very small hands and weak, tiny, (likely) hypermobile wrists, so when I lift free weights, the majority of the dumbbell's mass rests somewhat uncomfortably in the curve of my palm. But I've always been able to shake off this tender soreness and move through it, and it typically resolves within a day or so, so I’ve never really thought that much about it.

I completed a 50-minute chest, shoulders, and triceps workout that morning, and went about my day.

The leftist meme account moderator FakeMarkFisher was visiting town, as part of a cross-country tour to fight as many Americans as possible. (To my knowledge, FakeMarkFisher enjoyed many conversations and a couple of shots of Malört with various friends and readers, but wasn’t able to successfully get into fisticuffs with anyone). He’d told me he wanted to meet up, so I carted myself and my achey hand down to Humboldt Park, where we chatted about the city of Chicago's labor organizing scene, took a walk, then visited the Art Institute of Chicago to check out the new Pan-African exhibit.

I really enjoyed these photos of Senegalese dancer François “Féral” Benga, a gay icon during the Harlem Renaissance who also served as the muse to multiple photographers, sculptors, and anthropological writers:

My hand was increasingly throbbing as the day progressed, and beginning to generate heat. I tried to ignore it.

I was also struck by the contemporary photographs of Sabelo Mlangeni, depicting Black queer life within the House of Allure in Lagos:

As we walked around the exhibit, we talked about FakeMarkFisher’s beautiful, intellectual firebrand of a new girlfriend, and his intellectually disabled sister, who enjoys tormenting him by watching Mukbangs to spite his misophonia.

I was really enjoying the company, and the conversation, but was starting to feel very weak. I left the museum and collapsed into an odd fever at home, unable to find a comfortable position to lay in, or any sleep. I had no idea what could be wrong with me.

Friday, January 10

The next day, the pain had worsened. I found I could barely close or open my left hand at all.

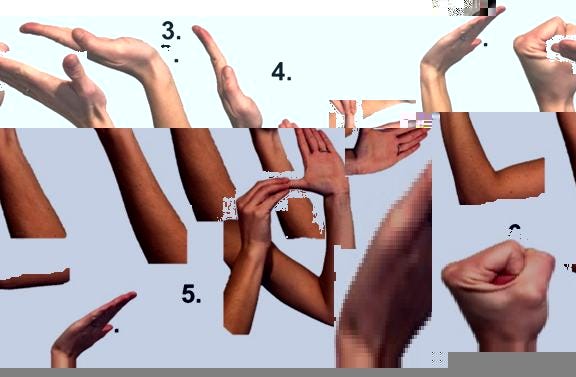

I began suspecting I had carpal tunnel syndrome, a diagnosis which fit my highly keyboard-dependent lifestyle and generally poor desk posture. I went over to the pharmacy to buy a cheap compression glove for my hand, took a couple of painkillers that ultimately did not help, and watched a ton of videos about carpal tunnel stretches on YouTube.

I spent much of that evening aggressively finger gliding and icing my hand, and went to bed with a bag of frozen corn balanced on my palm.

I believed that the problem was a tightness in my tendons that needed to be worked out, and so rather than rest my aching hand, I ministered to it obsessively.

Saturday, January 11th

My pain by this point had become debilitating.

I went into an urgent care armed with my self-diagnosis of carpal tunnel. The medical provider I saw was like most of the staff you encounter at urgent care facilities: efficient, bright-mannered, and sympathetic to my pain, but generally incurious about its etiology.

The urgent care model is not well-suited to any illness or injury that is complicated, difficult to diagnose, environmental in its causes, or requiring of intensive care. The last time that I reported to an urgent care, I had a month-long case of laryngitis that I knew for a fact had been caused by being in a classroom teaching and projecting my voice from 8 am every morning until 9 pm every night. Despite knowing that my condition came from vocal overuse, the physician’s assistant prescribed me an antibiotic I didn't need, and which, if I had taken, would have contributed to the rampant problem of antibiotic over-prescription in the United States.

Urgent care clinics exist to streamline the process of dispensing prescriptions for bacterial infections, simple viruses, and pain, and to relieve some of the pressure placed on our under-staffed emergency medical system. And the job of the urgent care provider is, broadly speaking, to dispense medications and provide short-term, symptom-oriented treatment for conditions that are easily recognizable, and from which the average patient can make a full recovery at home. When a patient’s situation is ill-suited to this service, they typically receive an unhelpful medication and a shrug.

This time, the provider at the urgent care prescribed me a round of the oral steroids methylprednisolone, which was supposed to relieve some of the inflammation from carpal tunnel. I was instructed to take six 4mg pills of methylprednisolone that first day, an additional five the next, then four steroid pills the following day, and so on.

I was also given a new wrist splint with a small thumb loop, because the physician's assistant noticed that my hand was swelling and she figured it was because my other restraint had been too tight. She advised me to follow what has been the standard care protocol for sports injuries for decades: to rest, ice, compress, and elevate (or R.I.C.E.) my hand.

No one warned me that corticosteroids like methylprednisolone suppress the immune system, or that they can provide such a strong energy boost and distraction from pain that a patient may potentially over-use and damage their injured body part.

Furthermore, no one warned me that icing only really benefits a fresh injury, and that it should only be performed in short stints of about 20 minutes or so, because prolonged icing without breaks can increase swelling by causing lymphatic vessel permeability, discourage the body from mounting a needed inflammatory response, and delay the overall course of healing.

No one that I consulted with at the urgent care (or several other facilities that I would go on to visit) seemed aware that the rest, ice, compression, elevation protocol has largely been scientifically debunked, to such a degree that even the researcher who originated the practice has retracted it.

The Saturday evening that I was first on steroids, I felt incredible! I was filled with an uplifting, yet somewhat impatient energy, and the pain in my hand that had been wearing away at me no longer seemed like it mattered. I still was unable to bring my thumb fully into my palm, but I could bend it somewhat, and the other fingers on my hand were no longer burdened by the pain radiating off of the thumb.

I watched the movie Nosferatu with a friend (and hated it), read the entirety of Please, Miss by Grace Lavery (and loved it), cleaned my kitchen thoroughly, then flipped open my laptop to write a 2,000-word advice column for a newly-out trans guy who wondered why becoming a man had made people treat him so nicely.

I wanted to believe my functioning was restored. I believed that with gentle use and continued icing and medication, my hand would soon be on the mend.

I was fooling myself.

Sunday, January 12th

The pain in my hand started flowing into my wrist and forearm. Fluid had begun filling the area, churning around inside me with a fresh, raw kind of sting. I kept ice on my hand almost constantly, when I wasn't massaging it or trying to use it to do the dishes or complete carpal tunnel stretches.

At night the pain would intensify, and I’d go into a bit of a panic, crying out to my partner that I was afraid I was going to lose my hand, and finding it impossible to sleep. The swollen tissue was getting hot, and I was starting to feel almost feverish again, thrashing and sweating late into the night.

Monday, January 13th

By about 4:00 a.m. on Monday night/Tuesday morning, my hand was so inflamed and painful that I decided to walk to the emergency room two blocks from my house.

The Weiss Memorial Hospital’s emergency room was dingy, and I initially believed I would have a very long wait, because there were about six people slumped in chairs sleeping all around me. When the nurse at the intake desk apologized to me for having to sit there among the resting bodies, I figured out that everybody else there was unhoused, and had come into the emergency room to escape the bitter snow and cold.

I was relieved to realize that the hospital didn't kick homeless people out of the space, as so many institutions do, and ashamed that the nurse thought I wouldn’t be willing to be among them. We all sat together as the wind whistled outside, our heads tucked into our chests, our hoods over our brows, and barely stirred.

Within about 45 minutes, I was taken back to be x-rayed, and was given a bed.

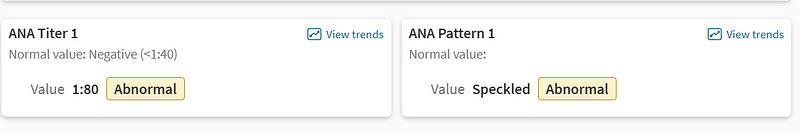

My X-rays showed no evidence of a fracture, which was no surprise to me. A warm and soft-voiced nursing student approached me and examined my hand, asking me to curl my fingers and thumb inward, which I could not do. I winced at every attempted movement, and she said sympathetically, “that really hurts, huh?”

I felt genuinely cared for, which relaxed me, even though there were no answers being found. My vitals were taken, and nothing looked out of the ordinary.

A suicidal woman in her mid-20s was brought in and laid on the bed next to me in the hall. She told a social worker that her boyfriend had broken up with her, and that her mother had recently died. She was given a scratchy-looking blanket and curled underneath it, on her side. An elderly woman was on a bed in the hall down from us, and she kept asking the staff when she would be given food and waving and smiling at me. An impatient male nurse told her that the kitchen wasn't open yet.

I waited with the other patients in silence for a long time while the nurses gossiped about their upcoming shifts, and the work-from-home telehealth jobs that they did for a little side money. A doctor came to me with a printout suggesting that I see orthopedist, and a prescription for Tylenol with an extra shot of hydrocodone. She said there was nothing else that they could really do to help me.

The role of the ER physician is to stabilize a patient who is on the verge of death, or has incurred a pressing and immediately treatable injury. But nobody really knew what was happening with me. I spent the rest of the day calling orthopedist’s offices, and that night worriedly tossing and turning.

Wednesday, January 15th

I traveled down to the University of Chicago's Medical Campus in Hyde Park to see an orthopedist and his assistant. I knew how fortunate I was, to have been able to book an appointment so soon.

By then my swelling had gotten significantly worse, and bubbled itself completely around the thumb pad of my hand. The primary reaction of the orthopedics team was to be surprised and baffled by the state of things. The inflammation was suggestive of some type of infection, and yet I did not have a fever; it was not only my thumb that was struggling to work, but the first two digits of my left hand as well, though it was difficult to distinguish some kind of nerve or tendon failure from the side-effects of swelling.

My doctor and his (very attentive and engaged) assistant Ricky turned my hand this way and that, asking me to bend my thumb and taking note of what made me wince, then declaring the whole presentation curious. I would come to find this type of reaction oddly validating; it was better to be an interesting medical anomaly than being dismissively told I had a simple, treatable condition when that so clearly was not the case. When medical providers took an interest in me, I could see their eyes opening up, as if the usual, dispassionate scrim they used to approach most patients had dropped away. I knew that it certainly helped my case that I was white, thin, and a man.

My doctor ordered I get an MRI performed as quickly as possible — before the end of the week. He also prescribed me a round of antibiotics for the swelling and possible infection.

“I don’t like to just throw antibiotics at a problem without knowing what it is,” he admitted. But my symptoms concerned him. Sure enough, I would show an elevated white blood cell count and other indicators of immune system engagement on that day’s blood test.

Thursday, January 16th

Thought my doctor had put a STAT order on my MRI, the earliest available appointment on the University of Chicago’s campus wasn’t for several weeks. I commiserated about this with my friend Madeline, who has been dealing with long Covid and chronic fatigue for the past couple years, and often has to book labs and appointments with specialists six or eight months in advance.

“Call a bunch of other places to see if they have available appointments,” Madeline advised me. “And keep calling every couple of days, to see if they’ve had any cancellations.”

I spent most of my Thursday tracking down various radiology departments with MRI machines in and around my city, forwarding photographs of my doctor’s notes and trying to convey the urgency of my situation to them. My hand was only becoming more inflamed and painful, and I feared that bacteria was eating away at me hand from the inside. Some kind of structural damage seemed more likely, though; I kept willing the upper part of my thumb to move and feeling a total absence of connection.

Eventually, I was able to locate an MRI appointment at 8pm on Friday, out in the suburb of Orland Park.

Friday, January 17th

It would be about an hour in an Uber to get there. Several of the cars that I ordered cancelled on me once they saw my destination — but one young woman with a Rihanna-filled playlist and aspirations of replacing her old sedan with a 2024 Genesis GV70 in matte grey did decide to spend the time on me. We enjoyed our drive together humming along to Umbrella and gabbing about our lives. At one point, her car pulled up alongside a gym, and together we salivated over a man in his mid-twenties doing side-crunches.

My experience getting an MRI out in the ‘burbs was altogether pleasant. The entire facility was sleepy and quiet, with most of the other departments closed for the night (I had learned from Madeline that most MRI machines are run 24 hours a day). I took out my piercings and my keys from my pocket and stored them in a small locker.

A technician gave me ear plugs, laid me out on the MRI bed, and arranged me into an awkward, sideways position with my hand extended and clamped into a hard plastic sleeve. Then she stepped behind her console and slid me into the magnetic tube.

I have been in fMRIs before for neuroimaging studies, so the loud droning and clicking noises of the MRI did not bother me. Several scans were performed on my wrist and lower hand, during which I had to stay absolutely still: 3 minutes frozen in place, then another 4 and a half, then another 3. All told it was about half an hour of posing and working not to move my body. The aching in my hand seemed to get worse, as if the magnet was shooting heat and pain directly into it, but that was probably my head playing tricks on me as I laid there with nothing to do.

On the way out, the technician gasped at the shape of my bloated claw and murmured, “My, that hand really is swollen. I hope they do figure that out.”

I told her that I hoped so, too.

Saturday, January 18th

My swelling and pain had gotten far worse. The fluid that had been filling my palm and wrist had now moved to the back of my hand, creating an uneven bubble that went all the way past the knuckle of my middle finger. Much of my forearm was also enflamed, and even walking around with my arm at my side was acutely unpleasant.

Any time that I wasn’t laying with my hand elevated atop pillows, I was soaking it in a hot bowl of water and Epsom salt, which didn’t seem to be doing much, but did pleasantly tingle and relax my locked-up joints.

The orthopedist’s assistant had told me to go to an emergency room if any of my symptoms got worse. I thought of him, and the possibilities if I allowed my condition to progress, and resigned to go in.

I knew there as no use in going to the ER right by my house, which had no one on staff who specialized in hands. But I was leery of taking a forty-five minute Uber down to Hyde Park for the University of Chicago’s emergency room, too — the ER had an average rating of just 1.6 stars on Google, and numerous reviews complained of 10-hour waits and hospital rooms with fresh blood stains on the ceiling.

I poked around on Google maps, comparing the rankings of all the available options. Thorek also had dismal reviews. So did Northwestern’s ER. I wondered how legitimate my emergency really was, if I could afford to be choosy about cleanliness and wait times.

But my hand was larger than it had ever been and I wasn’t feeling any better. I had less range of movement each day. I was unable to work, dress myself, make food, or lock my own back door. Besides, I had no appetite, and could barely sleep. I was growing fearful that I might really have to lose my hand, especially if I wasn’t proactive about treating it.

I found the nearest emergency room with actual positive reviews — just a quick bus ride two miles south of me, in Lakeview. St. Joseph’s Ascension had an average rating of 4.2 stars, and many patients spoke glowingly of the helpful staff, tidy facilities, and short waits.

And so I made my way down.

My experience at St. Josephs lined up with all the positive reviews. The moment I walked in, I was whisked away into a private clinic room with a nurse’s aide who took my vitals, jotted down notes about the medications I was on, and asked me about my pain. She made a copy of my ID and walked me down to a private cubicle that had a television just for me, and a soft pastel privacy curtain. Not five minutes passed before another nurse was with me, installing an IV to draw my blood and give me pain medication.

No one had even asked for my insurance information yet. I’d spent no time in any waiting room. Here, the priority was getting me care.

A physician’s assistant breezed into the room with a computer console, and pulled up my MRI results from the night before. She told me that my flexor pollicis longus (or FPL) tendon appeared to have torn. That’s the tendon that allows the thumb to curl inward to make a fist. Whether it was partially or completely damaged, she couldn’t say. It was possible that I also had some kind of cyst. My blood draws showed that my white blood cell count had begun to decline, though it was still elevated.

I already had a follow-up appointment scheduled with my orthopedist for Wednesday, and my vitals looked alright at that moment, so there wasn’t much else anyone in the emergency room could do. The PA recommended that I stop taking acetaminophen for the pain, and replace it with naproxen. She wrote me a prescription and told me to keep the thumb stabilized. I was sent, once again, on my way.

Monday, January 20th

Donald Trump was inaugurated as President. A series of Executive Orders passed swiftly across his desk, banning the use of the X gender marker on all federally-issued passports, defining gender as binary and fixed at conception, ending birthright citizenship, repealing civil rights protections, and calling for the mass removal of undocumented immigrants, especially from major cities like Chicago.

Predominately Hispanic neighborhoods and workers in the city’s service and restaurant industries braced themselves for a violent crackdown. Many businesses shuttered their doors. A neighbor of mine, who works in restaurants, told me that he wasn’t “pro-gang” by any means, but said that groups like the Latin Kings existed for a reason, and he hoped they would show up to resist the ICE raids using all means possible. I told him that in situations like these, I kinda was pro-gangs, actually, then I recommended he get a Signal account so he could talk to friends and co-workers about the raids securely.

We broke away, wishing one another good luck. The city felt poised for civil war.

I was at my computer that morning, trying to drown out my dread and use voice-to-text to grade a few student discussion board posts. Then my orthopedist’s assistant Ricky called me. He was concerned by all the fluid showing up on my MRI, and my still-elevated white blood cell count. He believed I needed emergency surgery performed on my hand that day.

“I can’t make you come in,” he said tentatively. “But I would recommend you get into our emergency department, or at any other teaching hospital, where they have specialists who can operate on your hand. We have a really good surgeon in the emergency room here today, and I’ve told him to prepare for you. If you can come in.”

“I got it,” I told him. “I don’t want to take any chances. I’ll be right there.” Then I hopped into an Uber along with my partner, and zoomed down to Hyde Park to get my hand operated on.

The University of Chicago’s ER was about as horrific as the reviews had made it out to be. Immediately upon entering, my partner and I were screamed at by multiple security staff, who told us that no one but patients were allowed in the room. My partner was sent to wait in the lobby of a building across the street.

Beside me, there was a woman in a wheelchair wearing pajamas and howling in agony. She wasn’t allowed to have a companion with her, either —the boyfriend who had been pushing her chair was sent away. When her name was called and she had to come to the front desk, she had to beg for someone to come move her.

On the floor of the waiting room there were many crumpled up snack chips, empty soft drink containers, plastic bags, band-aids, loose gloves, scarves, and long smears of melted ice and street sludge. Bodies were slumped in chairs all around me, heaving. The air was filled with a chorus of sneezes and wet coughs. A few patients paced angrily and complained they had been there for hours.

I was sitting there for probably about an hour. But one of the surgeons had been told to prepare for me. And so I was summoned, and brought to the back.

Being in the ER was becoming comfortingly familiar. I had my blood drawn, my blood pressure and temperature checked. I explained the whole elaborate story of my hand to a woman literally named Dr. Friend. She was good-natured about my long-windedness, and wrote in my chart that I seemed “pleasant and conversational.” An elderly Hispanic man in the cubicle next to me watched Evangelical Christian sermons and skateboarding videos on his phone at full blast.

I was visited by a young, handsome third-year medical resident, who worked under the ER surgeon who specialized in plastic surgery and hands. He told me they had looked at my MRI results and were not convinced I needed surgery that day. It was apparent something had gone wrong with my FPL tendon, but they weren’t sure that it was a complete snap.

He pressed down on the tip of my thumb and asked me to flex against it, and seemed encouraged by the slightest millimeter of movement.

“Do you have any idea how this could have happened?” He asked.

Every medical provider had asked me that. Had I been playing sports? Did something catch on my thumb and bend it all the way back? There really hadn’t been any injuries I could remember? My answer was that I’d just woken up feeling like this, it must have just happened to me in the night. This time I floated one additional detail:

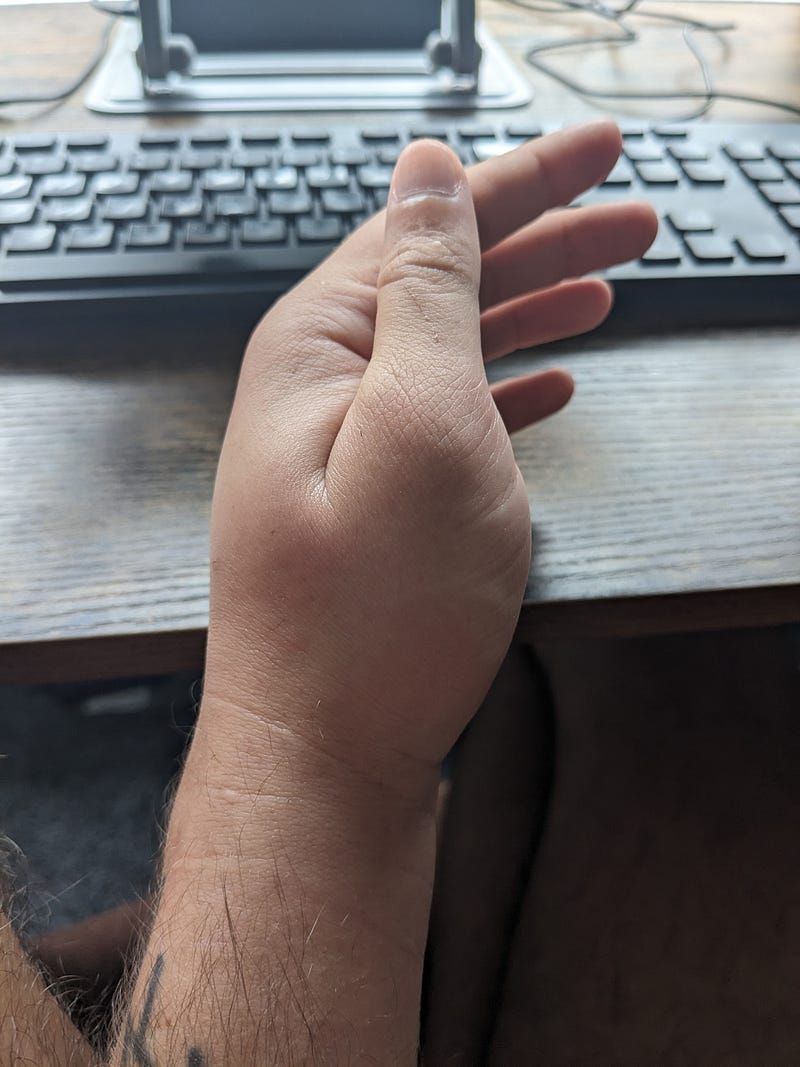

“A friend told me once that I might be hypermobile,” I said. Then I took the thumb of my healthy hand between my fingers, and bent it all the way down until it made contact with my wrist.

“Holy shit,” the resident said. He laid his own hand out flat, the palm down. “Can you bend your pinkie backward more than ninety degrees?”

I showed him that I could.

He perched his hand behind him on the arm of a chair, and bent forward at the elbow. “Are you double-jointed?”

I mimicked him. My elbow extended way farther back than his.

“Okay. Yeah. You’re definitely hypermobile,” he said.

It made sense, of course. Autism is highly comorbid with hypermobility, as well as connective tissue disorders such as EDS. All my life, I’ve been told that I sit wrong, and stand wrong, and in school I was constantly corrected for my physical weakness and the odd way that I held a pen.

Until I started taking testosterone and enjoyed significant muscle gains, I was unable to open doors or hold up heavy items without my wrists collapsing on themselves. I’ve always had to throw my full body weight around and pull big objects at odd angles to get anything done. And I have felt pain — in my knees, hips, wrists, and thumb pads — chronically, as well as a persistent tightness that begs to be stretched out with extreme poses and bone cracks. Everyone always tells me to relax and drop my shoulders, but I can’t. I’m always wound up.

To me, these were just the annoyances of regular life, something I was never offered any help for, only mockery. I had learned to ignore many of my body’s natural cues, because I’d been told so frequently that they were wrong and embarrassing, and I could be impressively oblivious to pain. I also slept in unusual, potentially damaging postures, with my hands curled up and pressed under my full body weight.

I knew that I could have twisted my FPL tendon to the point of rupture in the middle of the night without even noticing it, but doctors found that hard to believe. They could not understand how I related to my body, how little control over it I had or how absent my regard was for its well-being. They also have no idea I was the type of person to exercise vigorously even when I had a heart murmur or was afflicted with COVID, the type of person to use a standing desk everyday, all day long without breaks for a year until my knee nearly began to give out, or to walk 5 miles with an open bleeding gash on my heel and not know.

“My boss and I recommend you immobilize the thumb completely for the next three weeks,” said the resident. “So that the tendon can begin to grow back. We don’t think it’s torn, yet, and we want to prevent that.”

Then he outfitted me with a rigid plaster cast.

“You can type with this thing on!” The resident assured me. I’d told him that I was a university professor who taught online classes, and that a huge part of my daily job involved writing.

I smiled and thanked him, but the tightness and bulkiness of the cast had my forefingers almost totally encased. When I tried reaching for the keyboard, my heavy plaster thumb fell down with a thunk, and blocked me from doing anything.

That was probably for the best. If my injury had been caused by my body’s connective tissue falling apart, I probably shouldn’t go back to battering it with repetitive typing stress.

Wednesday, January 22nd

I returned to the University of Chicago to see my orthopedist.

“Oh good, they gave you some thumb stabilization,” he said about the cast — and then immediately opened it up and broke it off.

We were pleased to see that my swelling had gone down dramatically. In the past two days, I’d also been suffering from far less pain. I'd no longer been able to worsen my injury by continually trying to move it. My most recent blood test results showed almost no signs of inflammation, either. My white blood cell count was back to normal, and infection was seeming less and less likely as the cause.

“That doesn’t explain why this happened,” the doctor said, blowing a tuft of hair from his face. “You are a medical anomaly.”

He and his assistant prodded around in my palm, and noted that I was flinching away from them far less. I could bend my index and middle fingers almost without issues, and move my thumb from side to side. I still could not bend it inward, though.

“I don’t know what the emergency room doctors saw,” he said, “but I don’t see any movement on that tendon.”

“Are you trying to curl your thumb in?” the physician’s assistant asked. “Like, is your brain telling it to go in?”

“Yes,” I told them. “I’m trying to bend it, and there’s just…nothing there.”

I didn’t share this with them, but I had gotten high two nights before, which always makes me feel more attuned to my body. I’ve never really been able to understand how people use marijuana to treat pain, because when I’m zooted I’m suddenly hyper-aware of every single ache and point of stubborn tension in my body. And there’s a lot of it.

During my high, I wriggled my fingers around, trying to relax them, and I felt absolutely certain that a tendon inside my hand was disconnected. It was an unsettling truth that in my altered state I was able to finally accept. But I didn’t tell my doctors that. I couldn’t trust my high-mind’s diagnosis.

“You feel that?” my orthopedist asked his assistant, rubbing over a thick knot in my palm. “I think that’s the tendon. All balled up.”

We reviewed the MRI of my hand together. A huge glob of fluid surrounded the FLP tendon of my thumb, and it was lit up in bright white, in contrast to the normal meaty darkness surrounding the rest of my hand’s innards.

“But the scan doesn’t go up far enough for us to see where the tendon connects to the tip of the finger,” my doctor explained. “And there’s really too much fluid to see if the tendon is completely severed.”

He told me that when I’d come in that day, he’d been prepared to cut me open, “clean” out all the signs of infection, and stitch the tendon back together again. But now that my swelling was down, he wasn’t sure. He couldn’t tell whether the tendon had frayed, snapped, or simply popped out of place. And rather than slice my hand from the fingertip to my wrist, he’d rather collect more data — in the form of yet another MRI.

“We really aren’t supposed to be wasting medical resources,” he said, with the air of someone who is constantly getting lectures from his higher-ups. “But we need to know what’s going on in there. I’m sure you don’t want some purely exploratory surgery.”

I clenched my teeth and nodded. A few days prior, I’d been in so much agony I would have risked giving up the hand to find relief. But he was right. I needed to find out the source and the extent of the problem — if he didn’t understand the nature of the tear, he wouldn’t even know how to repair it. For all I knew, it was so ravaged I’d need a replacement tendon from a corpse.

So we scheduled yet another MRI, and another follow-up appointment for next week.

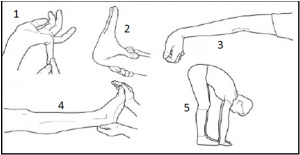

While I was in the orthopedist’s office, we ran a battery of additional blood tests. I was screened for rheumatoid arthritis factors, all of which came up negative, and for antinuclear antibodies associated with other auto-immune conditions, which mostly came back as “abnormal,” “reactive,” or “speckled.” If you want to play Gregory House, MD on my chart, here is what a few of them look like:

One blood test did initially flag as reactive for syphilis (which has been linked to inflammation of the hand tendons in a few prior studies), but additional follow-up tests ruled it out as a false positive.

I’d also begun considering that my injury could be related to being on testosterone replacement therapy. One reader reached out to me to share that their own case of De Quervain’s tenosynovitis (involving inflammation in the tendons of the wrist and at the base of the thumb) had emerged after multiple years on HRT. They said that their symptoms improved once they began using wrists braces at night.

The use of exogenous testosterone has also been found to increase the risk of numerous types of tendon injuries, including to the ACL and Achille’s tendon, as well as the tendons in the hands.

“Your skeleton doesn’t usually grow (much) [on T],” the trans person who contacted me said. “But your muscles do, which can put extra strain on your joints if you’re not careful.”

I brought up this issue with my orthopedist, who said it was a good thought, and that he’d spend some time researching it further.

“But we don’t tend to see these types of injuries with just testosterone,” he clarified. Usually, more serious steroids were involved.

For now, I honestly have no idea what is going on with my body.

I won’t be surprised if I join ranks with the thousands of Autistics who suffer from Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome or similar autoimmune disorders, or the likely millions of individuals who have developed severe health complications after multiple bouts with COVID. The appearance of autoimmune factors in my blood tests seems ominous. When I search online for the potential meaning of my results, a long list of obscure conditions emerge.

I have dear friends who live with degenerative conditions, as well as mystery ailments and diseases so rare that their doctors have never seen them outside of a book. I have a better sense than most of all that involves — the litany of office visits, labs, tests, and physical therapy appointments it requires, the piles of medications, supplements, orthopedic pillows, hand massagers, sanitary wipes, heart-rate trackers, assistive devices, and bed-bound entertainments that can help to make all of it bearable.

I am terrified of the future both personally and politically, and mourning the loss of my physical capabilities, but mostly I’m just taking things as they come. I’ve at least found it interesting to be a medical mystery, and appreciated the novelty of all these new travels and tests. I’ve had so many fascinating discussions with doctors who take my pain seriously, and entertaining asides with nurses and other patients while I wait for my appointments.

I feel cared for. And I am privileged to be able to access so much care — and, being a white, thin man, to have my suffering taken so seriously. My orthopedist’s assistant has literally lost sleep out of concern for me. Twice now, my orthopedist has been able to use his authority to secure me a quick specialist’s appointment. And if after all of these examinations, my current care team has nothing to offer me, I have other providers I could see.

I have a job. I have money to cover my co-pays. I’ll be hitting my insurance plan’s out-of-pocket limit this month, and then I can splash out on acupuncture and therapeutic massage if I want. (Is that what people who are good at accessing healthcare spend their insurer’s money on? I’m not in the habit of seeking care out. Is there anything else I can splurge on?).

I have a partner who lives with me who can help cook meals and sift the cat litter, and lots of friends who have offered me help. I can manage my life without a hand, at least in the short term, without disintegrating.

Still, it has been difficult to manage the stress. A part of me fears that the entire reason I incurred this injury was because I was already stressing so much — clenching and unclenching my body nervously in the night, having nightmares about book tours and work meetings and feeling the steady ache of constant, obsessive writerly productivity wearing on my body.

And it's all taking a strain on the rest of my body, too. The wrist of my right hand feels tight and tired, either from anxiety, compensatory overuse, or from some mystery autoimmune condition that’s attacking all of my tendons. I am terrified of losing what capabilities I do still have.

At times I feel that all of this is a punishment for the excessive amount of writing that I've done. Four books in 4 years, plus a novel that I banged out last August and have not published anywhere. And all those damn essays and social media posts and emails. All that fretting about how I would be received, and the opinions of others, and whether I was making the most of my so-called career, even when the foundation of that entire career was encouraging others to do less. I have never been able to relax. I still don't know how to stop curling up and clenching in the night.

Let’s discuss what comes next for this newsletter.

In the short term, I don't expect there to be a noticeable change in my release schedule.

I have a number of essays that were written prior to this injury queued up for publication — one of them is about the inherently regressive nature of “vanilla” sex; In another, I research the r/latebloomerlesbians subreddit and contemplate the experience of being closeted for decades, even to oneself. Another essay is about our culture’s universal fear of aging, and how that manifests in unhelpful “concerns” about the supposed dangers of transition. (That last piece sure proved to be a prescient one.)

I also have a number of shorter pieces and advice columns written that I can pepper into my release schedule to pad things out. My hope is to write (or rather, dictate) more of these more frequently, because they are so fun, fluffy, and enjoyable to put together. I like that in my advice columns, I get to explore relatively radical and challenging ideas in a really approachable format, and my Tumblr ask box never stops getting filled up with great queries from fascinating people.

I am going to continue to practice writing using voice-to-text. I was able to draft the majority of this piece using that method, and I think it came out reasonably well. Relearning my primary method of communication is daunting, but worthwhile. I woke up today absolutely itching to write, and thankful I still have the ability to.

I plan to dabble in audio and video formats for my work a lot more frequently. I really enjoyed making this YouTube video giving advice to a young Autistic person who wants to advocate against ABA therapy without over-exposing their own personal story. I think the video format lends itself naturally to responding to advice questions and introducing essential concepts from my work to a new audience.

I also anticipate live streaming a lot more, because frankly, being disabled is stultifying and lonesome, and connecting online to other freaky and radical thinkers is a major balm. This past Friday, Madeline and I held a live, post-Trump-inauguration processing session on Twitch, which brought many of us some comfort and perspective, and I’d love to carve out more spaces like that.

If you’ve made it through to the end of this very long update, I’d like to thank you. In the comments, I welcome speculation about my health condition, suggestions, recommended accessibility tools, and all manner of advice — I have not yet gotten to the point where I roll my eyes at being told to do yoga or try some random supplement. I recognize that many of my readers have lived with chronic health conditions and mobility limitations for a very long time, and are vastly more seasoned at navigating this stuff than me. Any wisdom or grievance that you have to share in that vein is welcome.

For all that I typically complain about it, I really do love being an online communicator, a poster, a streamer, and a writer. That I’m still able to project my voice out into the void is a fact for which I’m immensely grateful. Writing is what kept me alive when I lacked a real community; it allowed me to articulate an understanding of myself back when I lacked the language of queerness or neurodivergence, and it has been a blessed side effect that my attempts at figuring myself out have brought comfort and meaning to others.

I know that no matter how much my writing process might change, or my capacity to produce might ultimately be reduced, the potential to seek understanding and forge connection is still there. So thank you for being there, on your little end of the void, and for projecting all of your own brilliance and searching back in turn. Even at our most isolated and desperate, we can find one another in the dark.

Speaking as someone with autism and EDS who's wound up needing way too many joint surgeries, if you've hit your OOP max for the year, there are two things you should do:

1. See an EDS specialist and go over all of your joints with them, including a detailed discussion about what sorts of exercise and activities you like to do (lifting, etc.). They can give you a formal diagnosis if you don't have one already, and can help with the second thing, which is....

2. Physical therapy. There's proactive physical therapy you can do for EDS to strengthen the stabilizing muscles around the joints that can help mitigate-- not prevent, but mitigate at least-- the stretching of the ligaments and tendons. It can make a huge difference and lessen the likelihood of things like this (potential distress or tear/rupture to the ligaments or tendons) happening in the future.

This is not a punishment for all your writing. Your work has done so much for so many people, me included. It’s just a combination of overuse, possible T side effects, and autism-related hypermobility. Life happens. It just fucking happens.

The grief for your former abilities is the fucking worst. Feel your grief. Don’t shove it down. Let yourself be sad and furious and annoyed and allll that shit. There’s not much I can say except keep up the adaptations and see if you can find a 3D printer at the nearest library to print some open-source occupational therapy aids to make your ADLs easier/less painful. For writing, keep up the speech-to-text and use the inbuilt spell/grammar check as often as possible.

As for the insurance side of things, once you hit that OOP, work with the docs to prescribe over-the-counter stuff wrist braces, topical pain relief, etc. so it’s on the insurance company’s dime instead of coming directly out of your wallet. Check the website of your payor to find the medical necessity guidelines they use (if they use Interqual instead, hit me up) and your doc can write your clinical notes aligned with said guidelines, making denials much less likely.

All in all, I just wish you more low-pain days than high-pain ones. Surgery is likely the best option once there’s more imaging, but whatever happens, I hope you get some pain relief and recovery. 🫶🏽🫶🏽🫶🏽🫶🏽🫶🏽