October 28th.

I am standing on the corner of Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive, watching as over five thousand people gather in support of Palestinian lives. The mass of bodies crowding down Wacker is tightly knit and looks formidable, and I get to be one of them.

I’ve been to many political actions for many causes before, but this is one of the most diverse I’ve seen, in age, race, and diasporic status. Greying grandfathers hold the hands of young children, who lead the chants of “End the siege on Gaza Now!” and “I believe that we will win!” with courage exceeding any seasoned activists’. Mothers, aunts, siblings, and cousins stand in keffiyehs and hijabs, pushing strollers and handing relatives snacks from their purses. Young men run across the street to greet one another in Arabic, laughing and clapping each other’s backs, so pleased to be united. Black and brown college students stand next to middle-aged Asian men in business suits while white retirees wave black, green, red, and white flags. Soon I will get used to these sights, but I won’t stop being gently awed.

Before the group can really get moving, a man on the loudspeaker says, the coffins need to be brought to the very front. Everyone else should get far back behind the banners, he says, please. At first I don’t know what he’s talking about, but then I see them held toward the sky: dozens of tiny white coffins made of cardboard, draped with the Palestinian flag and printed photos of the dead.

The reverie of the moment is intercut with solemnity; it’s impossible not to think of the drained, ashen bodies we’ve all been watching on our screens, not to feel the incredible grief of each family that has lost numerous members, of every generational line that has been entirely wiped out. These protestors carry reminders that half a world away there are remnants of lives, of a rich culture, just left out rotting.

At the protests to come, I will also see heavy-looking bundles wrapped in white, representing the loosely shrouded bodies of people whom Israel has killed and who may never find a more lavish burial. Everywhere, people will be holding these effigies of death, tender remembrances of the kindnesses Palestinians still extend to their martyrs even as the bodies pile up, unrecognizable and impossible to count. Still they cover them with blankets, hold their hands and kiss their mauled faces and pray for them to deliver a message with them to the afterlife.

The death toll will only be rising and there will only be more need of these remembrances. We all get used to it.

November 9.

The President is in town for a fundraiser, so we have come together to hold him accountable for the billions in aid and hundreds of soldiers the U.S. has contributed to Israel’s genocide. But they’ve changed the location of his speech at the last moment, in an attempt to shake us all off.

It does not dissuade us; as I arrive to the original location, a long line of young people in keffiyehs and sweatshirts tell me that we now must relocate to West Town, several miles away. We all load into the train cars together, our cardboard signs and Palestinian flags making it easy to find one another — and for the city’s police to track.

Just when the train is about to approach the station closest to where Biden will be making his speech, the operator announces that we’ll be going express, skipping the next several stops. We all groan knowingly; this is a tactic, meant to dilute our numbers and wear down our resolve. We pile out onto the platform and see that every upcoming train is marked Express too.

“We’re less than a mile away,” one protestor calls out to us. “We are walking ya’ll!” and thankful for her leadership, we follow her.

Biden’s team tried to evade us, and when we arrive, the police still have us cordoned off more than a block from where he will actually be. But we are not dissuaded; for hours into the crisp night we gather chanting for the Intifada Revolution, clapping, shaking our signs, banging our drums. We must be loud enough to ensure Biden hears us, the organizes say. When we receive word that he’s arrived, we build a mighty collective roar.

Many times at this protest, I notice Arab men filming or livestreaming the proceedings, or Facetiming relatives so they can watch the action too, a stunned look of gratitude on their face. I’m not normally good at interpreting facial expressions, but even this registers to me: they’ve never had so many people caring about them before.

Two generations ago they were driven off their lands, robbed of their homes, had their legal citizenship revoked, watched their olive trees burn. For decades they have been battered, bombed, and demonized, and now suddenly a great number of people care, and they never expected to live to see it. I see multiple grown men cry just taking it in. This, too, is a sight that I will soon get used to.

November 11.

Loyola’s students have organized a small and covert protest outside the new Veteran’s Center, where U.S. Senator Tammy Duckworth is giving a speech. A group of predominately Arab young women coat their hands in red paint and leave prints on the street. They hand each of us printed-out lists with the names and ages of the dead, mostly the infants, who span countless sheets. These too are caked with fake blood. When the protest is done, I will fold it up and store it in my jacket’s breast pocket, where still it stays. A needed witnessing, a reminder of the lost innocence across my chest.

There are a few organizers on the inside, military veterans themselves, posing as interested in Tammy but really delivering updates to us. The Center is open to all students and everyone here has a campus ID, but we are not let in. The girls hurl their bodies into the door at a crucial moment, trying to force their way, and campus security throttles them back. A little later, an elderly Black veteran approaches with a cane and a key and begins to open the door. Campus security harasses him too and we scream and scream that he deserves to be let in.

In the end, we never do get to see Tammy, but I’m awed by the courage and charisma of the young women who have organized this action. Their chants are witty and resonant and we remain outside for hours blocking the windows with Palestinian flags and earning supportive honks from passing cars until Tammy slips out, cowardly, from the back door.

At a certain point a white man in his 60s approaches and stands alongside us in his Banana Republic zip-up sweater and his slicked back white hair. He asks a few questions and we explain to him that Senator Duckworth is there.

I assume the worst, and I’m wrong, because quickly he joins us in chanting “Tammy Duckworth what do you say? How many kids did you kill today” and “Free, Free Palestine” and “Stop Funding Genocide.” Then he wanders off for a moment, returning with bags loaded down with falafel, pita, and hummus.

“Look everyone, khal [uncle] brought all us some food!” one of the girls announces, and the young people are hungry and broke as colleges students are wont to be, so they begin opening up the bags. He gives them an upward fist of support and then departs.

I work around a lot of middle-aged white people in smart zip-ups and sweater vests, uncontroversial liberals who are easily disturbed by vitriol and certainly won’t be turning up to protests like this. I’m heartened by this man’s presence. His support and the fire inside these young women makes me finally believe it when we chant “I believe that we will win.” I’ve always felt a sardonic remove when uttering such words before. But now I realize that what’s right can never die, it awakens in all those alive that hear it.

November 18.

Hundreds of us gather in the freezing cold at the Buckingham Fountain, just a few yards from the highway and the lake. We are wearing layers, leggings under pants, long sleeves tucked into sweaters buried under coats, the rows of our bodies blocking the worst of the wind but also making the speakers leading the chants impossible to see. It does not matter, we are hear for one another. Together we are the event.

For a long time we are there, repeating and repeating the phrases we’ve all come to know so well. End the Siege on Gaza Now. There is Only One Solution, Intifada Revolution. Long Live the Intifada. Israel Bombs, the USA Pays. Palestine is Our Demand, No Peace on Stolen Land.

In the past, at protests, I used to be highly neurotic, too aware of the unique nasality of my voice, afraid of being the last voice to call out or the one that kept a statement repeating for too long, wondering needlessly whether I should be repeating phrases like “I can’t breathe” when people like me obviously can, or “Whose Streets? Our Streets!” when perhaps the streets should not be mine.

These actions have freed me of my navel gazing, which was always purposeless and entirely too self-involved. I am one body among hundreds that helps make the crowd, I am to be a megaphone. I am echoing the collective will of the people, my own mewlings of support subsumed within the growing wave of everyone else’s. I don’t need to think about everything, I can just be a part of the great resistance all around me.

I’m a solitary white person and a writer, and it took me far too long to welcome the modesty of my place. Suddenly though, I’m incredibly moved by the chanting, and feel a shared power in our all getting to amplify it together. This must be what people feel at church, I think, or at synagogue or the mosque. This must be how people who haven’t been poisoned with individualism feel. This is how it is to really be a part of something, not for how it looks or because you think you should, but because you have no choice, it is simply what you do.

We are asked to lay down for a twelve-minute “die in,” representing the (at least) twelve thousand people whom Israel has killed. But there are so many of us, pushed togethering in spaces so cramped, so we have to collaborate to arrange this arm and that leg so we don’t get in one another’s way. I am filled with peace as we all lay there, staring into a pristinely clear sky. I think of the silence between the dropping of bombs, how the Palestinians never know rest and how we cannot either.

Then, perhaps only four minutes in, the organizer takes to the megaphone and lets us all in on the secret: Get up now, get up now, we are taking Lakeshore Drive! This was never meant to be a die-in, that was all a ruse, but it only worked as one because so many of us were able to be pawns and had no inside knowledge for the police to steal from our private messages.

We dash down the plaza and into the street, a few of us sitting down in the road with banners while the cops try to block the rest of us off with their barricades and bikes. What ensues is terribly exciting, the organizers leading us by the dozens over the fences and into the barricades, elderly people and children pushing up against the cops just as doggedly as teens and twenty-somethings. Cups fly, bodies launch themselves over barriers, and we scream and scream LET US IN.

The cops’ large metal barricades rise up in the air, and some police press them outward into us, trying to knock us back, but then one man hurls himself between the joints, injuring himself as he hits the pavement but creating a gap, and then we all rush in like a flood, taking the highway, yelling and gesturing backward to welcome more down the hill and into the road with us.

We hold the highway for hours, much of the traffic through the city’s main artery having to be redirected to avoid us. I watch young people scale traffic light poles to hang Palestinian flags and keffiyehs from the lights. I see Muslim men lined up on the sidelines, buffeted by us, kneeling to pray facing Mecca. I march with my comrades down the length of the street, tiny toddlers just as precious as the ones whose lives as been stolen, young adults with futures as promising as Moaz and Bisan, and elderly folk like those who still remember the united and free Palestine.

Plastic buckets clap out a rhythm while street performers join us too, singing Free Free Palestine in a honeyed harmony. We are proving to be quite the hassle for the city to deal with, together, but they’re having to get used to it.

November 19.

I am at a Powwow on the north side, wondering guiltily if I belong there. I have my own complicated relationship to Indigeneity, though the simple version is that I’m just a white person who will never know what was taken away and can’t pretend that I do.

I’m here with a friend who has their own internal conflicts that rhyme with mine, but who can name their people and has formed relationships with many in Chicago, too. Their presence gives me permission, I feel, to have a seat at the table, to eat chicken stew and chat with aunts about their family members’ health conditions, to touch handmade regalia and awe at the silhouettes of birds on the shawls and the beading of people’s earrings and necklaces, and to bear witness to the dancing and the drums.

I sit with my legs crossed and a blush of embarrassed longing on my face as I watch the dancing of the Tiny Tots, the Jingle Dancers, the Fancy Shawls, the Prairie Chicken Dancers, the Grass Dancers, the Intertribal competitions. One of the Prairie Chicken Dancers carries a Palestinian flag in one hand with him always, and it soothes an ongoing ache in my heart. Here, as everywhere, is a reminder of the proud people of the resistance, whom I’ve rapidly found myself feeling dedicated to.

I’m usually so numb, typically so profoundly jaded after doing so much activism for so many causes that were liberally diluted and made into nothing but exhausting busy work. I’ve been dragged to so many actions that seemed to do nothing, convinced to lobby for so many politicians that turned their backs on me. My hopelessness had hardened me and made me selfish. But in the fight for Palestinian lives I’ve truly felt like a cherished yet modest piece of a collective, freed of my usual rumination and remove. I am in it, a moving breathing part of it, every day. It deeply touches my heart, and holds me there.

A few times, my friend invites me to join the dancing and I demur. I want to but I don’t want to make an ass of myself. But all this watching feels like taking, and I realize that I must give of myself too. Then a young man who has joined us (and who tells me he has two left feet) finally finds the courage to join the men’s dancing, and he gestures for me to join him, and of course I do.

I have zero self-efficacy here; I stick out like a broken thumb. Still I bounce on my knees and bring my feet down shyly and keep moving, and when the crowd in the circle is large enough, I forget myself, feeling at ease. Then a plain clothes dance for men is announced, so I have no choice but to participate.

My new friend and I make the rounds alongside men in Bears jerseys and ribbon shirts, and in an incredible act of generosity, I am chosen to be one of the finalists in the dance. I want to flee out of shame at my ineptness, but there is one of the Prairie Chicken Dancer with his Palestinian flag, at my side at once, showing me the motions, showing such inclusion and kindness to me.

“You want to bring your feet down heavier,” he tells me, demonstrating. I can feel the weight of his moves; they shook the ceiling when I was downstairs eating my stew. I try to stomp more heavily, but I’m still so cautious, so white, so at an emotional remove, watching myself do something rather than doing it, so afraid of taking up too much space. “You have to think of who you are dancing for,” he tells me sternly, and then suddenly it makes sense.

I think of my grandmother who passed many years ago, the one who explained to me the best she could who all our people were, and who would be the proudest of me being here. I think of my father and the empty searching quality he always had to him, and my great-grandfather who didn’t pass as white but nonetheless tried. I think of the kind of man that I want to be, and of all the men around me who are kicking their legs up and swinging their arms, dedicating the whole of their body weight to cultural preservation and resistance. And then I think of the Palestinians, both the strength and the tenderness they have no choice but to show as they fight murderous soldiers and offer hugs to shaking, dust-coated, orphaned children.

A teenager in what looks like hospital scrubs and a bandana rushes into the circle too, though he is not one of the finalists. He kicks his legs back, bending forward, darting around me, almost floating above the floor. Repeatedly he locks eyes with me, flashing a battle-ready confidence, sending me some of his energy in steadfast support. He and the Prairie Chicken Dancer dance with me, beckoning me to be something more than what I am.

And I dance. And for the first time in my life, being singled out for my awkwardness does not feel bad. The drumming goes on for ages but I keep moving, flush-faced and still too timid, but a growing stoniness rising within. We are dancing for something, not just for ourselves, and we can’t let our petty worries bring us out of it. I have been invited into this circle to be a man and to participate in the maintaining of a culture, and so now I must really be a part of it, rather than just doing it as if I were doing it. Never before have I actually felt called to be a man, and shown by other men how to do it.

I’m given a prize for my performance, a gesture I know I don’t deserve, but such things aren’t supposed to be measured based on who is deserving. You don’t reject such a gift. And so I accept it, and sit back down with my friends, and we remark to one another how fully good we feel being in such a welcoming space and getting to contribute to it.

I stick around afterward packing up chairs and carrying them down the stairs, into the back of the church where the powwow is hosted. Being part of the collective, being a man and being of use, not turning away even when I feel exposed in my weakness, these are the things that I must do, and I’m incredibly thankful I get to do it.

November 24.

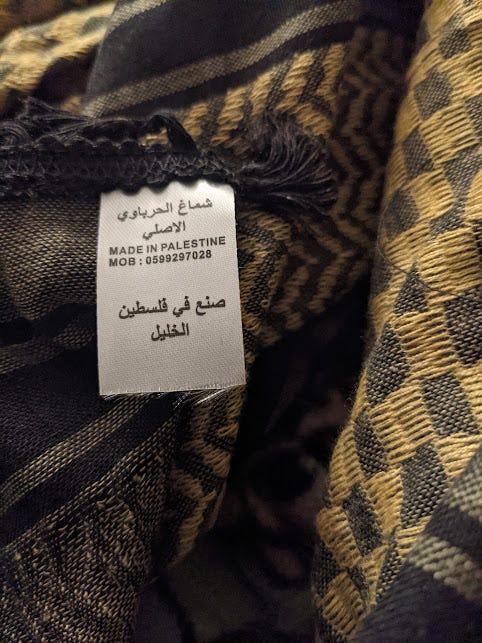

In protest of Black Friday, thousands of us are together again, taking to the streets. I’m masked up, layered, and now wearing a keffiyeh, an olive green one from Hirbawi, the sole manufacturer or the scarves in Palestine. A hand-drawn Palestinian flag on a posterboard is aloft in my hands as high as I can hold it. I stomp down the center of Michigan Avenue bellowing out the chants without hesitation; when the crowd I’m in dawdles a bit and gets far away from the speakerphone, I call out what I’m hearing in as deep a tone as I can muster, to ensure that more people hear it and repeat it farther down the line.

We walk past Victoria’s Secret, where a few dozen comrades have blocked the doors with their banners and their bodies. The company has a plant on occupied Palestinian land and so for this moment, the customers are barred from coming in or out, just as the Palestinian people are barred from leaving or coming into their country. We raise our posters and chant Shame on You, Shame on You over and over. Cops are pushed to the sidelines, no longer trying to keep us off the road, no longer able to control us, just protecting the businesses from us. Their role as the defenders of capital is clear as ever.

We continue down the street, to one of the largest Starbucks’ in the world. Three stories of customers sit at tables by the windows, staring down at us warily while we shove the reality of genocide into their faces. We scream and chant and shake our banners and flags, and none of them can even pretend to be disinterested. On the rooftop two white guys in tourist’s clothes swear and flip the bird at us and we return it; in short order, they tire out. Shame on You, Shame on You, Shame on You we cry. Stop Funding Genocide.

Several Starbucks customers film us, some emotion dawning on their faces. So many of us are waking up emotionally these days. Perhaps they are awakening too. A day later, at a teach-in at the First Nations Garden, I will hear a white man in a KN95 say that he’s spent most of his life just going through the motions, working and surviving and staying numb. He’s felt more feelings in the past month than in much of his adult life he tells us, the joy and the horror. But it’s good.

It’s good to feel alive, to be connected to the genocide and the triumph of the resistance rather than to try and be comfortable. There’s a pathetic desperation to attempting to remain fully emotionally regulated, forever evenly keeled, unmoved by the world’s events. There’s an insanity to it that those of us who have actually been insane will not tolerate. We’ve reached the limits of our privileged denial. It is good to feel it, to be dissatisfied to our cores, ready enough to see unjust settler colonial states burn down.

This man could have been narrating the contents of my brain. I’m once again humbled that even my revived empathy is nothing unique.

When the protest ends, I get on the train with my posters and a Palestinian flag that I bought from a street vendor. Normally I stuff these accoutrements away as soon as the event has ended, fearful of drawing stares, but this time I hold them up proudly. Buying the keffiyeh was a commitment to being visible and outspoken in my support of Palestinian lives, no matter where I go or who I am with. I will wear it to my work’s Christmas party, continue decrying genocide online, bringing it up during book press and interviews. I no longer obsess over the opinions of those whose complicity disgusts me. I will make enemies if I am in the battle. I remember who I am dancing for. I feel strong.

On the way off the train, a man with wispy hair in a blue Cubs sweatshirt approaches me. “Min il-maya lal maya,” he says to me, From the River to the Sea in Arabic. “Falasteen 3arabiye.” And then he gives me a fist.

I give him a nod and a limp-wristed fist back. “Absolutely,” I tell him, wishing that I knew the words in Arabic to return. I make a mental note to learn them. I don’t have to be afraid of what I don’t yet know, or ashamed of people noticing I don’t know it. I can learn. I can do this for them.

They have done so much to strengthen me already. I’ve never felt like I had any business aspiring to be strong before, but at last my growing power has a purpose. I can be strong for them. I am only strong because of them. We are each of us dancing together, and I really could get used to it.

This is beautifully written. It describes the process many go through when they become connected to a movement. It can transform a person. It is the antidote to all the selfish, egotistical, individualistic, hedonistic aspects of our capitalist culture that keeps us divided and fearing one another. This is what we need to do - join with others to demand justice. It is the best way to live.

Such beautiful reflections on this time, this growing collective power, captures a lot of my feelings, thank you.

“It’s good to feel alive, to be connected to the genocide and the triumph of the resistance rather than to try and be comfortable”. Such a welcome reminder, thank you