Multi-Factor Authentication Is Inaccessible

Autistic people, ADHDers, and people who can’t afford cell phone service are excluded by most authentication systems

Autistic people, ADHDers, and those who can’t afford cellphone service are excluded by most authentication systems

Last January, I was out thrift shopping with my friend Imani when my phone suddenly stopped working. We’d made it about halfway through a long row of wool coats when I went to check my email and found I had no signal.

“That’s really weird,” I said to Imani. “My phone isn’t connecting to any towers.”

“Maybe the store just gets a bad signal.”

“No, that’s not it,” I said. “There are no bars, not even empty ones. And no little LTE or 4G symbol.”

“Try restarting it?”

I turned my phone off and back on again, and still there was nothing. I was used to getting a crappy signal inside buildings, but the absence of any connection was new. I have to admit I felt a bit of panic rising in my stomach — I was worried Trump had finally gone and gotten us into some nuclear conflict that had destroyed our satellites or cell towers or something. But when we stepped outside for a smoke break, Imani’s phone worked fine. She had a different provider than I did.

We walked to a coffee shop around the corner, and I connected to its Wi-Fi. I checked Down Detector and discovered that, yes, AT&T service was utterly kaput throughout all of Chicago and had been for well over an hour.

“Well, fuck,” I said. “My students have an exam coming up, and they need to be able to reach me. I guess I have to go home.”

When I got home, I tried to log into my university email and found I was due for authentication. A little while back, the school had made two-factor authentication (2FA) mandatory every two weeks or when using a new device to access email, HR documents, and class registration info. I’d signed up to authenticate via phone call. But I couldn’t take a phone call now — I had no cell service. So I couldn’t do any work.

I tried to log into my AT&T account to check in about the service disruption, but its site required — you guessed it — 2FA via a call to my phone. So I gave up. Service remained down for the rest of the day.

Google Promises ‘reCAPTCHA’ Isn’t Exploiting Users. Should You Trust It?

An innovative security feature to separate humans from bots online comes with some major concernsonezero.medium.com

At some point in that email-free, phone-free day, a troubling thought occurred to me: What if a Loyola student can’t afford a phone? How are they supposed to log into their email? What about people who can’t afford a phone but need multi-factor authentication (MFA) to access their banking info or utility bill? Is there a whole class of people who are just totally excluded and shut out by our current approach to security?

It turns out that yes, there is. I checked in with a few friends who have been or currently are homeless, and they confirmed that MFA has frequently proven to be the bane of their existence. One of them was Maeve, a woman in her mid-twenties who got completely locked out of her bank after she ran away from an abusive partner — and lost her phone in the process. Another guy I spoke to, Steve, told me that while he tries to keep working devices on him at all times, it’s far easier to get Wi-Fi access as an unhoused person than it is to consistently pay for cell service. For months, he could not cancel his utility bill for an apartment he no longer lived in because he couldn’t verify his login via phone or text.

People who don’t have consistent cellphone or internet access aren’t the only ones screwed over by these systems. Many people with autistm or ADHD also find 2FA and MFA incredibly difficult to navigate. I’m autistic myself, but it was only after my frustrating day with zero cell service that I started to really reflect on how cumbersome I find authentication systems to be. I recently tweeted about it and wasn’t surprised to learn that many neurodiverse people feel similarly.

I’ve generally avoided turning on 2FA or MFA until I am absolutely required to. It always felt like such an infuriating waste of time to me. I thought it was just because I was impatient and tolerant of risk. But once I got to reflecting on it, I realized it was tied to my Autism.

2FA and MFA systems are confusing, distracting, derailing, and stressful if you have any kind of cognitive disability at all. Neurodiverse people experience differences and challenges in our executive functioning (our ability to plan, sequence, and shift gears between tasks). Speaking very generally, most of us find it hard to multitask or filter through a bunch of competing stimuli while remaining on task. It takes a lot of willpower and energy to initiate an activity and switch our brain into “focus mode.” Having to jump between different applications and devices to access our work tools makes autistic inertia even more debilitating than it usually is.

Autistic people and ADHDers also tend to get distracted and anxious with too many notifications, prompts, or alerts. If an authentication process requires us to open a separate app and go hunting for a code or password, we may lack the momentum to do so. If I do manage to break through inertia and open my email to go hunting for a code, I risk getting sidetracked by the other messages in my inbox. Since some codes last only a few minutes, I might lose my progress entirely and have to start over.

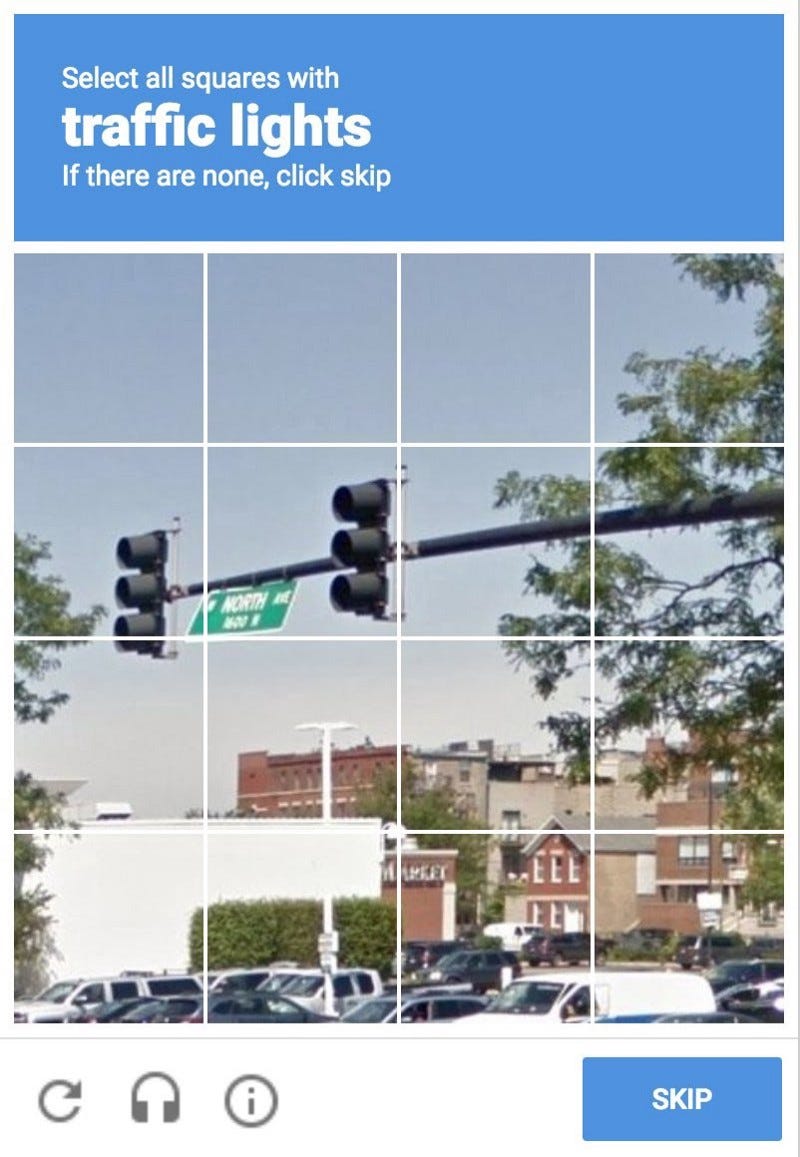

When we do have the energy and focus to switch over to email or an app and find an authentication code, many of us will still lack the ability to copy it correctly. For many of us, comorbid disabilities such as dyscalculia and dyslexia cause numbers and letters to jumble together into an indistinguishable mass. If verification requires completing a photographic or alphanumeric CAPTCHA, neurodiverse people’s detail-oriented and hyper-literal processing style may mean we can’t figure out the answer. “Is that symbol an I or an L? Does that tiny strip of pixels in the lower-left corner count as an image of a traffic light? Does the pole count as part of the light?” Questions that seem “obvious” and intuitive to neurotypicals can vex the hell out of us.

Neurodiverse individuals struggle to parse visual noise, and many of us are either totally freaked out by clutter or utterly unable to visually filter through it. This means that we often misplace our phones, charging cables, ID cards, and notebooks filled with passwords. This means physical authentication keys aren’t a solution to our problems, as we’re at high risk of losing those items too. We also forget passwords a lot. If you’re trying to log into your HR software to download your W-2, but your phone is lost among the piles of books and dirty socks on your bedroom floor, preventing you from authenticating in time, the odds of rage-quitting are incredibly high.

Historically, the way many neurodiverse people (including me) have coped with these issues is by turning MFA off. I only use it at work because I am required to. I’ve turned it on for a few key accounts that are high profile or contain sensitive information, but usually I have to decide between using a service “unsafely” and not using it at all. There are many apps and services I’ve begun to sign up for and then abandoned because the bureaucratic minutia involved was too severe a barrier to cross.

I don’t know what the solution is to this problem, but I do recognize the root of it: 2FAand MFA outsources the responsibility for keeping a platform safe away from the company that developed and runs it and places that burden onto users instead. Asking individual users to authenticate with a phone, a special app, or a code sent to their email is time consuming, frustrating, and for users with disabilities or economic barriers, sometimes completely impossible. It’s a Band-Aid that many services have reached for in recent years in lieu of developing systems that protect the entire platform, even in the presence of user exhaustion and error.

I imagine the alternatives that will prove the most feasible will vary by platform and user. A solution that might work for an autistic, housed person who works from home (like me) might have no utility for someone who is homeless and unemployed. And if we lived in a world where all apps didn’t mine mountains’ worth of sensitive data from us, we might be able to distinguish between the level of security needed to access our Spotify account, say, and the security needed to log into our bank. That’s a whole other accessibility issue worthy of consideration, by the way — ensuring that all users understand and can freely consent to having their information recorded or sold.

We’ve got to start exploring other ways of letting people into their accounts — and of locking them out. Otherwise, we’re just going to continue excluding the very people most social systems already isolate the most. For those of us who have a disability or are living in poverty—and for all those who experience both—it’s already hard enough to get and maintain a job, watch our finances, keep track of key documents, and pay our bills. We don’t need a bunch of technological gatekeeping to make that even more difficult.