This piece was originally published Feb 26, 2018.

I was a child in the 90’s, during the Asperger’s diagnosis boom. More and more kids were being identified as on the Autism spectrum. The checklists were getting to be well-known and more widely utilized, leading to more identification of something that had always been there. Some people mistook this as an increase in Autism, rather than an increase in knowledge. These people typically panicked, assuming more Autism (and more Autistic people) had to be a bad thing.

Autism was getting to be well-known, but in very limited, stereotyped terms. Trouble with eye contact. Repetitive play, lining up trucks or cars. Meltdowns that were obvious and troublesome. Poor academic performance, at least in some areas. If you weren’t “bad enough”, or weren’t bad in certain ways, you wouldn’t even be considered. I was not diagnosed with anything.

A Conventional Autism Checklist:

Are you the parent of a child?

Is your child not meeting developmental milestones?

Is your child excessively interested in trains?

Does your child thrash or bite and scream?

Does your child rock in place?

Is your child a boy?

Is your boy child disruptive but good at math?

Does your child not talk much, and not make eye contact?

Do you feel burdened by your child?

Do you feel like dealing with your child makes you an Autistic Warrior Parent?

If so your child is “a person with autism”!

— — — —

Common knowledge carried even more weight than these checklists, even in the minds of doctors, psychologists, and teachers. Autistic children were boys. They were rude and blunt, the type to kick mom in the shins or chew on the rug for hours or shit themselves with rage. They were interested in machines and very good at math. They were trouble. They were not nice or friendly or kind. They were, as Asperger himself once supposedly said, less of a human and more of a thing that looked like a human.

I was obviously not those things. Strike that. I was not obviously those things. I was assigned female at birth, loud and cheery, talkative. I used words that most children my age didn’t know, a common Autistic trait that nevertheless didn’t match the stereotype of Autistics as withdrawn and wordless. I had an obsession, but it wasn’t a very masculine one: I was in love with bats, collected bat dolls and plastic toys and read naturalist magazines about them, cramming my brain with knowledge. I was precocious and did well in school.

Socially, I was tolerated by a large friend group until middle school; I was odd enough to be funny, and smart enough to be of use. Eventually, I stopped being tolerable; I wanted to talk about things that didn’t interest, or weren’t supposed to interest, middle-school-aged girls. I had no interest in makeup, purses, boys; I said weird things, I didn’t carry myself the right way or know when to stop making a joke.

I was not a problem. I had problems, but my problems did not ever become anybody else’s. I grew and struggled, having more and more trouble making friends, but did so in relative silence. I was still doing well enough for people to assume I had things under control. When I failed at something, it was because I was not trying hard enough, not because of a disability. The only assessments I received were for a high IQ and motor problems. Nobody connected any dots, drew any lines to Autism. Nobody knew any better.

Family History.

It is 2014. I am at my family’s annual vacation to Cedar Point. We go every year, on the same dates, and do the same things, every time. Over and over. We are a people who love routine and structure. We go every year and everyone is expected to go. We do not communicate expectations. They simply are. We do not discuss emotions much.

I am in a hot tub with my boyfriend, my sister, and my cousins. I just graduated from my PhD program. I cried while my mom tried to take my photo at graduation. I am shaking off the odd feelings of having achieved something that doesn’t register as much of an accomplishment in my family — I am not married, I do not want kids, I do not make as much money as I theoretically could. They do not express disapproval. They’re not unkind. They just don’t say much of anything.

My cousin is in the center of the hot tub, asking me about the field my PhD is in, psychology.

“Do you know much about psychological disorders?”

“Not really,” I say. “I’m a researcher. I study how the average person thinks, I don’t focus on what’s, like, wrong with people.”

“Oh.”

“Why?” I ask. “Do you want to know about the things that go wrong with people?”

There’s a pause and a tilting of his head. I ask, “Do you think there’s something wrong with you?”

This is an inane and hurtful way to talk about mental illness. I know better. But I say it like that, anyway. I had a drink at the Chili’s on the outskirts of the amusement park and I’m next to my boyfriend, and being around him makes me want to perform, be funny and bombastic and rude. When I’m trying to be likable, I’m at my worst. I become my least appropriate, most loud self.

My cousin gathers his thoughts. He squints. “…Do you know much about Autism?”

Genetics.

Nobody knows much about what causes Autism, and anybody who claims to know is a huckster. It hardly matters why Autism happens, because it’s not a curse or a thing to eradicate. It’s a source of difference, a beautiful bit of plumage in some of our chests.

But there are correlations. It does cluster in families. It appears to be partially genetic.

My cousin tells me that someone in the family has been diagnosed with autism. For this family member, it was a relief, an explanation of the things they had found difficult and perplexing in life. My cousin got to thinking about this. And he got to learning a bit. There, in the hot tub, he shared with me his theory that nearly our whole family was Autistic.

His father, and our grandfather, are unemotional, blunt, and not good at taking social cues. Our grandfather conversationally steamrolls anybody that he can, always dispensing facts, never aware when his words are annoying or offensive. No one in the family is good at understanding or discussing emotions. Everyone is a bit flat in their affect. Everything has to be highly consistent. Few members of the family enjoy trying new foods or going to new places.

The family loves work, saving money, no-nonsense conservative ideas, football, and talking while not looking at one another. My highly emotional father was perplexed and infuriated by my mom’s family’s flatness. Sometimes I have been, too.

As my cousin rattled off the signs, I was struck with self-recognition. It all made perfect sense. But I felt kind of numb as he told me. A bit threatened. I brushed him off verbally, even though I knew what he was saying was profound. I always know when something brain-shattering is happening to me. Even if it takes a while to see the impact.

A Love of Research.

When I got home from that vacation, I burrowed into myself. I searched my mind and personal history for evidence, confirmatory and disconfirmatory. I was drawn, suddenly and unceasingly, to information about Autism created by Autistic people. It was an obsession that would hold my attention for several years.

I was already familiar with the #actuallyautistic movement on Tumblr. I had started following blogs by Autistic people, like Real Social Skills and Amythest Schaber’s Neurowonderful. I’d come to learn that Autistic people came in all genders, and were not all good at math. I had learned that, contrary to what I’d been taught in Psychology courses, Autistic people had empathy, and wanted friends, and were capable of being loving and kind. But for a long time, my interest had stopped there.

Now I was realizing I was probably Autistic, and my hunger for information knew no bounds. I followed every blog on the subject I could find. Located Amethyst’s Youtube videos and watched them in multi-hour spurts. I found videos by Rian Phin and MainJelly. I found blogs written by Autistic people who could not verbally speak, but could type or express themselves using adaptive software. I read a few books, but it was hard to find good ones. Nearly every published work was by a frustrated neurotypical parent, or a therapist who didn’t understand, and didn’t want to.

I followed Reddit threads and Tumblr tags obsessively. I learned that Autism had many lesser-known signs, like having an odd laugh or unusual gait. I learned about stimming, the process by which Autistic people zone out and self-soothe via engaging in repetitive sensory behaviors. I bought kinetic sand and sat on the floor of my apartment, playing with it and staring out the window.

I was slipping on an identity like a pair of tights, reflecting on how it fit and suited me. The more information I gathered and personal narratives I consumed, the more everything made sense. I couldn’t stop. I was comforted and disturbed by the depth of my self-recognition. It was the beginning of a long process of self-inquiry, one that is ongoing. One that will probably go on forever.

My brain was a hunting dog, and its teeth were latched on.

Getting an Autism Diagnosis as an Adult

Autism is rarely diagnosed in adults. Most clinicians cannot diagnose Autism at all — unlike Depression, or Bipolar, or nearly any disorder, it can only be diagnosed by specialists, following a specific and lengthy assessment process. Getting a referral to a specialist can be difficult. Some therapists will not even consider it possible for you to have Autism, and will not direct you to a specialist, if they think you’re a girl.

Autism assessments were developed and normed using a mostly-cis-male population. The assessments were originally created with the understanding that Autism is caused by an “excessively male” brain. Girls, afab people, and people of color have historically been under-diagnosed. Many specialists and clinicians still think of Autism as being a condition for white cis boys.

I am a researcher, a psychologist, and an expert in psychological measurement. And I know that taking something that exists on a spectrum and turning it into a binary category is always, always, always flawed. It kills variation and reduces our capacity to study relationships between variables. People get excluded arbitrarily. So I view all diagnostic categories with suspicion.

I know, also, that psychological categories have always been biased by racism, sexism, transphobia, homophobia, and classism, to name just a few. Black people who wanted to escape bondage were considered sick with “runaway slave disorder”. Women who did not want to have children were once considered “antisocial”. Being gay was a disorder until the 1970’s. Countless people were institutionalized and lobotomized for the way they loved. Being trans is still seen as a mental illness by many. People with mental illness are still seen as less capable.

I am also aware that no psychologist will ever know an individual as well as an individual knows themselves. Yes, we are biased beings, and often there are gaps in our self-knowledge, but a one-hour, once-a-week appointment with a professional is never going to overtake our own mountains of intimate personal experience.

Our therapists and doctors do not see us in the dark of the night, crying in the shower and striking ourselves with hairbrushes. Our doctors and therapists do not watch us eat our meals, or avoid eating; they do not track how often we take long, zoned-out walks. They did not sit beside us in class or on job interviews. They don’t know what we do in the bathroom, in private, when we need a breather from a party. They never inhabit our heads.

An official Autism diagnosis is validating for many people. But it is flawed. If I want people to understand what my neurotype is like, and what an Autistic brain can be like, it’s not especially helpful to regurgitate age-old, deeply biased diagnostic checklist and recount the ways in which I fulfill it. I’d much rather give you a detailed, personal account of what Autism means to me.

My Autism Checklist

Sound Sensitivity.

I am a joyless hateful bastard because laughter puts me on edge. When the chess pieces move in my boyfriend’s computer game, the clicking sound makes me want to shriek. Ambulances, honking cars, yelling or loud chatter — it all makes my mind go turbulent with confused, angry thoughts. My body tenses up. The guy at the café playing Duolingo on his phone is jabbing me in the stomach with his auditory rudeness. When the jukebox turns on at the bar, I have to leave.

Light Sensitivity.

I am in graduate school, in my office, in the dark. I come in when no one is around so I can keep the lights off. It makes the screen easier to see. It makes my brain work better. I am sitting in an office chair, my body cocked at an odd angle, my feet pressed up against the wall.

My adviser comes in. I scramble to turn on the lights.

He looks me up and down. “You’re getting pretty weird, aren’t you?” he says. He thinks years of graduate study has made me like this. No. I was always like this.

In classrooms and offices, the lights are headache-inducing. I have trouble not squinting or feeling rage on a brightly-lit train. I shower in the dark. I use the toilet in the dark. Soft yellow lights are a delight. I need the sun but I love grey days. When it’s dim, the world stops vibrating. The intensity has been dialed down. Everything relaxes.

Texture.

I’m a kid in Kentucky visiting my relatives. Their driveway is magic. It’s covered in round, bumpy pebbles in a variety of sizes. The pressure is divine. The variety is stimulating. I spend as much time as I can standing barefoot on its surface. I tell my family how much I adore it. They’re amused. It’s cute how I get into strange things like this.

In stores and at parties, I can’t keep my hands off things. If it’s bumpy or ridged or capable of being ripped and destroyed, I am devoted to it. If I don’t have something to fiddle with, I have trouble continuing the conversation.

I can’t wear belts. Can’t handle the pressure on my stomach. Lots of clothing is too stiff to wear, or too structured. Holding or ripping paper makes painful static fill me. My arm hairs stand on end. Food that is too soft is repulsive.

It is worth being this picky, to get to experience the orgasmic joy of a pine cone in my hand, or a rough surface against my feet.

Childhood Social Issues.

My friend Samantha Lewis asks if she can have my brownie. I give it to her. I point at her and wink and say, in a really strange voice, “You can keep the napkin, babe.” Everybody explodes in peals of laughter. I show everyone at the fifth-grade lunch table my training bra. I call my dad a bastard because I saw someone say it in a movie. I use the exact intonation the person in the movie did. During a fourth-grade unit on the Presidents, I march around the room yelling LBJ LBJ How many kids did you kill today.

People laugh or reprimand me when I’m odd. It’s hard to predict which is gonna happen. A mom is helping out at lunch and she says something about the milk being too cold. I say, “You’re not just whistling Dixie, brother.” She gets offended because I called her brother. She doesn’t understand it’s a thing from a Looney Toon. She calls me sister in a corrective way. It feels wrong but I don’t know why.

My best friend’s parents hate me. They see me picking my nose, sitting oddly, adjusting a front wedgie while sitting in their living room. They are constantly upbraiding me for violating rules I was never told about. It seems like something about me is inherently disgusting and freakish. I am not good at pretending to be any other way. The only solution is to withdraw into myself.

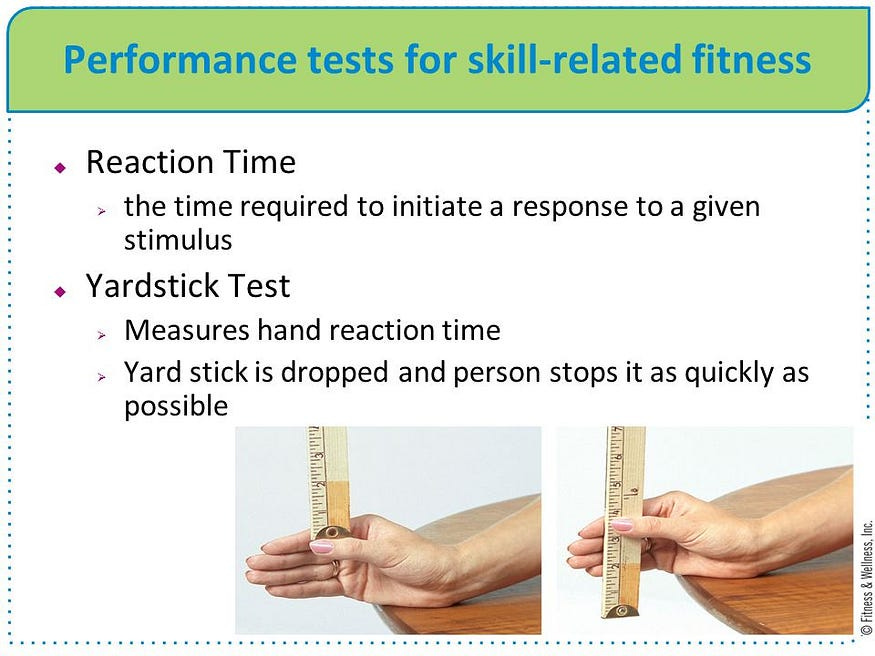

Coordination and Motor Skills.

I am put in Special Ed Gym. I practice catching a yardstick with my thumbs. Usually I can’t get it. The whole thing slips through my hands. I do wall push-ups. I cannot do a sit-up. I can’t jump. I struggle and struggle and no one can understand why it eludes me so much. I cry over it. In my regular gym class, I am talked to in a delicate, fake, pitying way. It makes me feel horrible.

My handwriting is so bad I have to skip recess and practice it. I can’t sequence a task as simple as throwing a ball. The gym teacher has to mime it, slowly, show me how to aim by pointing my finger at my target. He teaches me to skip by dividing it up into painfully slow moves: step, hop, step, hop.

My posture is terrible. I don’t know how to sit normally. My Girl Scout troop leader, Mrs. Henning, yells at me for sitting on my knees, every single fucking day. Sit like a lady, sit like this. Get off your knees. I need the pressure. I keep doing it.

I still sit like that, 22 years later. My posture is still bad. I curl up on myself constantly. It feels good. I can’t catch a ball or learn a complicated dance or do a sit-up, still. There are things my body cannot figure out no matter how carefully I try them. People always think I’m not trying hard enough.

Hygiene and Grooming.

I’m in third grade and my friend Tahnee Hasan is doing my makeup for a dance. She spends an hour carefully ministering to my face, applying foundation, lipstick, eye shadow in multiple colors, mascara. It’s nice to be treated this lovingly, but it also makes me self-conscious. It feels wrong to be done up like this. It feels like a violation. But she is being so kind to me. My reaction doesn’t make sense.

When I see myself in the mirror, I break down in tears. My mom chastises me for being so rude to Tahnee. It’s not that her makeup job was bad. It was just wrong. I hate the feeling of the powder on my face. I’m confused by the dark-eyed, dark-lipped face in the mirror. It is hard to look at. I can’t see what I look like. I can’t tell who I am. The pieces do not integrate int a whole.

This pattern repeats every time a group of friends tries to give me a makeover. I am always the one who needs a makeover, it’s clear — I do nothing with my face or my hair. They curl and spray and crimp, they smear on gloss and slip on bangles. I look in the mirror. Who is that? What am I looking at? It doesn’t make sense. I can’t see it, really. I cry and cry and wash it all off.

I don’t like working on my appearance. Looking in the mirror is disturbing. Caring about these things is a waste of time and a torment. I can be pretty but I don’t want to try. I am best off when I don’t think about it at all.

Body Awareness.

I am always bumping into things. I don’t know how wide my hips are. I can’t look at an article of clothing and estimate if it fits. I have no idea if I am taller or shorter than someone. When I hit puberty, this lack of awareness curdles into something toxic. My body feels wrong, and wide, and curvy, and too much. I try to shrink it and punish it. I look at my hips and stomach in the mirror and cannot tell when they change in size. All I can do is hate my body, feel that it is discordant and wrong.

Whenever someone tries to take my picture, I feel panic. I cannot control how my face is arranged, how I’m sitting or standing. They want me to smile and I can’t do it, not without looking in a mirror first, which I also don’t want to do. The lens is a beady, judgmental eye. I lose all sense of self. I start sobbing. This happened at every single school picture day as a child, and at my undergrad and graduate school graduations. I have never outgrown it. Only selfies are safe.

Social scripting.

I am not naturally good at being polite or normal, but I can learn the rules. I know to say “How is your day going?” during a lull at the café counter. Before a party, I think about a few current events I can ask about. I reference people’s Facebook posts in person a lot. I plan conversation topics weeks ahead, sometime: I’m going to see X at this party, so I will ask him about his trip to Scotland. I will say: Y.

I notice turns of phrase and intonations people use, and I borrow them to seem more human. I learned, at some point, to say “like” and “um” more than I needed to, to seem approachable. I got better at emoting the more people I observed.

I have learned how to sound sarcastic and funny, but it’s hard to sound enthusiastic. People often think I am being insincere or mocking them. At home, after an event, I repeat conversations in full, both what I said and what the other person said, to sort out if it was an okay interaction. I repeat people’s words and try to mimic their facial expressions to make sense of them.

On the phone, and in large groups, I am a mess. I don’t know when it is my turn to speak. I have to be silent and polite, or rude and heard.

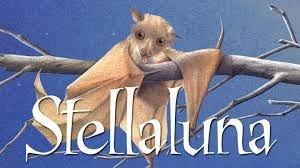

Special interests.

My first obsession was bats. I wanted to be a bat biologist. I collected dozens and dozens of toy bats, organized them on shelves in my bedroom, kept detailed records of their names using a checklist I’d written by hand. I read all about them. I knew all their scientific names. Learning about them was my way of loving them. It made me feel close to something I identified with more readily than people.

As a teenager, it was psychology. I read the entire DSM-IV: TR through, cover to cover. Inhaled text books. Took college-level courses while still in high school. People were perplexing to me, but fascinating as well. Psychology helped me to connect with something I didn’t naturally understand. I diagnosed all my friends. Asked overly probing questions. I wanted to connect and I wanted to fill my brain with the brains of other people.

A new special interest comes every few months. All my spare time is devoted consuming information about it. I’m filled with joy and love during those times. Every scrap of info gives me life. Videos, forums, books, blogs, wikis, I want it all. I spent years learning about gender issues. I read obsessively about trauma reactions. I obsessed over eating disorder recovery and the science of body size. I fixated on the world of fiction publishing and became a near expert at it. I got into vintage fashion. I learned everything about Mad Men.

Right now, I can feel a passion for figure skating blossoming in the back of my brain. I’m watching routines, learning about how the judging works, following all my favorite Olympians on Twitter, and looking at ticket prices for Stars on Ice.

I love the feeling of latching on to things in this way. I can’t choose what I become obsessed with. It just happens. And for months or years it becomes pure pleasure to learn about that topic. It is a superpower; I can learn so much, and so quickly. I can locate so much joy in just fucking around on the internet. Eventually my hyper-focus directed itself toward Autism.

Over-Identification with Non-Humans.

People often think Autism is characterized by lack of empathy, but that isn’t the case. In fact, one prevalent theory of Autism is that it involves a glut of empathy — we empathize too much, including with inanimate objects. Identifying with people and things so intensely can be painful. And draining. And it can be confusing.

All kids love their toys, and many children rotate which stuffed animals they sleep with so that none get “jealous”. But I truly felt that mine were alive. As a teenager, I felt guilt and pain throwing away old toys and Furbies, as if I was betraying actual living beings. I still feel emotions for objects, especially ones with faces. For years I thought this made me pathetic and immature. I would feel an urge to kiss a Pikachu doll on my shelf and wish it a good night, but stop short, thinking such urges made me an awful, shamefully childlike person.

I have trouble feeling anything for babies or tiny kids (with some exceptions), but I adore small animals of every kind. I feel deep identification with them. I can see myself in the posture of a squirrel more easily than I can another person. As a child, I desperately wanted to be an Animorph or a Pokemon or a bat. Animals and fantasy creatures were easier for me to relate to. They seemed more similar to me than many humans did.

I played The Legend of Zelda: Links Awakening for the first time in third grade, and became fixated on Link. He was androgynous and angular, but pretty; his appearance and dress transcended gender. He was elfin, not quite human, and nonverbal, like many Autistic people. He was a solitary sort, but adventurous and brave. I still identify with him deeply, find comfort in anything that makes me more like him — dying my hair blonde, wearing long, tunic-style dresses, traipsing around parks in brown boots . Every time I find myself in the woods I still think about being Link and exploring the Lost Woods.

If there is a character on a show or in a game that is an android or or a cursed, transformed creature, I’m guaranteed to feel deep empathy with them. Gary Numan (who is Autistic) created an alien-like stage persona that allowed him to be flat-affected and strange, but still captivating.

I resonate with that. I am an unusual fuzzy creature, a character on a screen in a beautiful suit coat, a genderless fae running through the woods, a robot trying to blink at you a normal-seeming amount.

Eye contact.

I learned at some point that eye contact is normal. I read about the informal rules of it. How frequently you’re supposed to do it. How you have to do it, but not too much, or for too long. I learned to fake it masterfully. I’ve even been complimented on how natural and appropriate my eye contact is. But every time I talk to someone, every single time, I am thinking about it and taking pains to make sure I do it normally.

When I’m beside someone, looking at the road, a video game, the TV, or even just the wall, my head clears. I find it easier to express myself. I can make brief eye contact with members of a crowd when I’m lecturing a class or giving a talk, but personal, one-on-one eye contact is intense. I can do it. I am devoted to doing it reasonably well. But it takes a lot of effort, and it’s exhausting.

Nonverbal shut-downs.

I can put words to anything but my own emotions. When I’m sad, or angry, or trying to resolve an interpersonal conflict, I am nearly nonverbal. All I can do is sob and dance around what I want to say. It frustrates and perplexes romantic partners and irritates family members. But I know, at this point, that it’s non-negotiable. I’m in distress, I try to open my mouth, and the words are gone. I’m filled with static and I’m crying. I can write down how I feel, when I’m alone and reflecting on it, but I cannot verbalize it.

I cannot connect emotionally with people, when they’re face to face. I try to tell my partner all the things I love about him and I start crying. I have to say kind things in a sarcastic way, or jokingly, in an odd voice, while not looking at him. I cannot bear my soul to friends when they are near. I have to write it down.

I can’t be warm and emotionally supportive when someone around me is visibly upset. I am far away, my heart is small and my brain is fuzzy. On paper I am perfect. I am a non-entity in person.

Stimming.

There are so many ways to experience pleasure in this world, and so many of them have been labeled incorrect. I am still re-learning my favorite ways to move, to touch. I was always so afraid of seeming inappropriate.

I love to rub at my shaved head. I love to cut my hair. The sound, the feel, the creative destruction, the fluttering of the strands to the ground. I love sitting on the sink and staring at my pores (but not my face) and squeezing everything out. I can pick at my skin for hours. I used to get lost in it. My mom would find me, as a teenager, perched on the sink and wrecking my skin, and she’d try to pull me away from it.

I love rubbing at bumpy things. I like rocking in place. I like listening to repetitive, soothing music and zoning out. I like ripping at my hangnails. I like pain. I love pressure. I like walking for hours until my legs are sore. These things soothe me when the world is too loud or busy. Which is often.

My fingers are hungry for something to manipulate. Slime to poke and key chains to rub and jewelry to fiddle with. I take a sip from a water bottle every thirty seconds, practically. I flap my hands when I feel A Lot. I push my nails into my hands and hurt myself, mildly, when I feel overwhelmed. It summons me back to reality. When life is really bad and I’m truly miserable, all I want to do is strike myself in the arms or legs with a hairbrush or hit myself in the head. I do this strictly in private. I have learned it terrifies other people.

Hyperfocus.

I have written all 3,829 words of this in one energetic spurt. It came out with zero effort. I once wrote a 300,000 word novel in about a month. It wasn’t good, but it was a pleasure to write. When I’m focused, writing is effortless for me. I go into a trance, and everything drops away. In a flash a draft is written, an inbox is cleared, a mountain of essays is graded. I am a riot of productivity.

I know I look faraway and glassy when I do it. I’m short-tempered and pissy if someone tries to pull me from the spell. It takes a lot of energy, too, to trance out like this. If I hyperfocus for more than a few hours, I am exhausted for the rest of the day. But I keep doing it. I love to disappear into my work. I feel like a robot. It feels like the truest me, really. I’m free of self-doubt and performativity. I get to stop thinking about whether I am being appropriate or normal. It’s an immensely pleasurable little death.

Understanding and naming internal states.

I don’t know I’m hungry until I’m starving. Sometimes I am filled with sadness or fury just because I need to stand up and stretch my legs. I can’t always understand what I’m feeling or why. I don’t recognize my needs until they are extreme. It has gotten me into trouble — I’ve denied myself sleep, calories, social contact.

I moved to Chicago thinking I would not need to make new friends; I was certain I’d just marry my work. I was suicidally miserable within a few months. I found myself crying all night and Googling things like “How to Make Friends” and feeling pathetic. Out of desperation, I got myself into an abusive relationship, and didn’t realize the abuse was making me hate myself until a couple years after it had ended.

I am slow on the emotional uptake. I didn’t realize I had post-traumatic symptoms until I had taught a class on PTSD two or three times. I didn’t grok that I was nonbinary until my mid-twenties, after years of ignoring it. I didn’t realize I was overly involved in other people’s emotional baggage until I was 27 years old. I never pieced together that my dad had been emotionally and sexually inappropriate until I was 28. I didn’t realize I was probably some kind of Autistic until my cousin told me in that Cedar Point hot tub.

But I get where I need to be. I am introspective. I love to learn about the mind, about my mind. It just takes me a while.

How to Score My Test.

When a child gets an official Autism diagnosis, they get a label and a pile of heavy expectations. They might get an aid, or they might end up in special education classes. Their parents might drag them to appointments where they are punished for talking about their passions, or they might be forced to make eye contact even though it is painful to them. They might be judged by teachers or underestimated by the world. Their parents might write shitty blog posts about their melt-downs, or make heartwarming, saccharine videos about their love for the garbage man. Years later, some self-congratulatory high school quarterback might bring them to prom and be praised for it.

There is a slim chance that the child will get disability accommodations that are actually useful. Maybe, if their parents are fantastic and their community is educated, they will get to sit in a room with dimmer lights and be allowed to fiddle with a fidget spinner. More likely, they will be expected to stop stimming, start looking normal, and shut up.

An adult with an official Autism diagnosis will get even less. There are no guaranteed benefits, no changes to the workplace or school or life that can be counted on.

I have no desire for the paperwork. It would not make my life better or easier. And it would not satisfy people who have decided to doubt my understanding of myself.

I have passed my own self-imposed Autism test. I developed it carefully over the past four years, and I’ve spend hundreds of hours reflecting upon it and challenging it. It has passed my muster. It has proven, time and time again, to be a useful understanding of myself. And since the whole purpose of this exercise is greater self-knowledge, that’s all that really matters.

How to Interpret the Results.

These results give me permission to be odd. They free me to seek out stimulating activities that soothe me and help me focus. They allow me to sit in the dark, in an odd posture, free of judgement. They encourage me to be as Autistic as I am, or want to be, and to not judge that ad a failure of maturity or self-control or loveability.

I am getting better at using these results. I try to tell people when things around me are a sensory burden. I try to not see myself as pathetic. I am working, always, to relocate the parts of myself that I had to bury when I was a child and I kept getting told I was acting wrong. I am trying to not be angry with anyone for shutting me down or stifling me. They didn’t know.

I am embracing Autism as an identity, and I’m using it to find community wherever I can. Each time I meet another Autistic person, I feel validated by the flapping of their hands and their broken eye contact and the way they can talk ad nauseam about the things they love.

I want people to know Autism manifests in a lot of different ways, and that all kinds of people have it. I am trying to normalize needing sound-cancelling headphones and fidget toys and quiet moments in the dark.. I’m working to make people realize that my neurotype is not a thing to be eradicated. I am trying to teach people that Autism is a superpower and a vulnerability and a beautiful, natural mark of distinction. I’m starting to believe it.

— — — -

Autism Resources

The Autistic Self-Advocacy Network