Names.

In a blue plastic drawer beside my bed there is a manila folder that contains my birth certificate, my certificate of name change, and my…

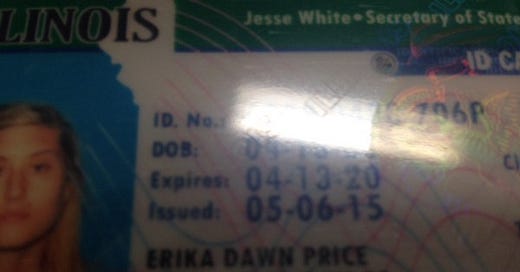

In a blue plastic drawer beside my bed there is a manila folder that contains my birth certificate, my certificate of name change, and my social security card. The former document is 26 years old; the latter two are 8. The first reads Erika Dawn Bohannon, the others say Erika Dawn Price. If I were to be really agonizingly precise, my full name is Erika Dawn Price née Bohannon, PhD. Six words, two of which I chose to take on, the rest of which were given to me.

Erika.

First things first: Erika. I am named after a soap opera actress. Neither of my parents had a particular admiration for the actress, actually — they just like the sound of “Erika” as a name. That, and my dad had never met an Erika that was ugly. This was one of his primary criteria. He told me so.

That same rule applied to my middle name, Dawn. There was a girl at a gas station named Dawn, and my dad thought she was pretty, and he’d never met anyone named Dawn who was ugly, so he assented to the name. From what I can tell, he was not good at generating names himself, just good at criticizing ideas my mom volleyed.

Another name up for consideration was Robin. My dad shot that one down. He had a big fluffy shock of red hair, which he was endlessly insecure about. My mom has imposing double-D breasts. These two traits made giving me the name Robin unconscionable. What if their daughter inherited both, my dad wondered? People would call me Robin Red-Breast!

I know this is ridiculous. No one would ever think to say that, to call me that, because it makes no sense. But such were the machinations of my dad’s mind. He thought too quickly, and with too much paranoia. And so Robin was struck from the list.

I know a few of the other options. Had I been born a boy, I would have been Ryan. Had I been born on Easter (two days prior to my actual birth), I would have been named Bunny. Before I was born, my great-grandmother embroidered and framed a piece of off-white cloth with the outline of a girl in a rabbit costume, with the words “Bunny Bo” stitched above it. It hung in my nursery until I was six years old. I loved it; I loved rabbits and small mammals of all kinds, and for years I kinda wished I’d been born on the right day, to make that my name. My dad was relieved that I was not born on Easter. If my name had been Bunny, I would have become a stripper, he said.

My sister’s name, Staci, was probably chosen using a similarly arbitrary method. No ugly namesakes allowed. No potential for crass nicknames would be tolerated. For her, they also considered the name Shannon. It would have suited her just as well as Staci. But that wouldn’t do, they ultimately decided; they could not have a child named Shannon Bohannon.

My mom wanted to make sure both our names were spelled interestingly. Erika is the less-common variation of the name, but the more logical and cooler-looking one. I despise people who spell Erica with a C; it looks weak. I don’t understand people that spell it with both a C and a K. I am envious of Erykah Badu. I wish I could pull that spelling off. When people spell my name incorrectly in email (when they could easily look it up), I silently fume. Every now and then I will meet someone and they’ll ask me how I spell Erika. I am always flattered; it’s invariably some guy who’s dated an Erika or Erica who, like me, had a very strong opinion about her consonants.

My sister’s spelling, too, is rare. People always guess it’s Stacey. Growing up, it was impossible for either of us to find factory-made personalized mugs, pens, or necklaces. This bothered Staci far more than it bothered me. When Coke ran its “Share a Coke with ____” campaign this summer, my sister’s name was unavailable, but there were Coke cans printed with mine. They even spelled it right.

All in all, I like my name. Erika is a prickly, spiky name; it bespeaks attitude, and maybe strength. It has strong consonants and it’s said quickly, spittingly. You can picture it blipping across the screen, captured as sound waves: clipped and sharp and not exactly pretty. You can see clearly that it is derived from a masculine name, Norse and humorless. It means “leader”. My sister’s first word was “Erika”. She pronounced it like “air-kah”. In college people said it like “Urka” sometimes. It’s buried in the name of this continent. I look like an Erika, I’ve been told. I like it.

Dawn.

My middle name, Dawn, is flattering as well. I like that it is uncommon — there are whole nations of girls with middle names like Elizabeth and Rose. But Dawn is unusual. It has a nice melancholy edge to it. It is literally crepuscular, but also filled with hope. My middle name says that I am dark and strange and quiet, but also the entry-point into all that is light and living and good.

People say it suits me. That I look like a Dawn. I don’t believe that quite as easily as I buy that I resemble an Erika; Dawn is a very pretty name, sadly beautiful actually, and I’m just not that stunning. But I am very glad to have it. My dad used to say that when I was famous, I could use Dawn as my celebrity surname. Erika Dawn has a decent enough ring to it. I use Dawn as a pseudonym whenever I need one.

Bohannon.

Then there’s my original surname. It comes from the sticks of Tennessee, in the Cumberland Gap of the Appalachian Mountains. It’s a hillbilly name, weird and easily mispronounced. For the first eighteen years of my life it was slaughtered by teachers, announcers, doctors, and debate team judges. A bland white girl with no other reason to be othered by people, I was oversensitive about my name. I hated how it sounded and looked, the dubious way people said it.

All of this is to say, when my dad disowned me I was happy for the excuse to change my name. Bohannon was sloppy and anonymous sounding; no one of prominence would ever be called that, I thought. Even my dad thought that — why else would he suggest using my middle name as a stage name?

Price.

So when my dad called me up one evening in 2004 to tell me I was cut off, disowned, rejected, no longer his daughter, the first thing I did was march into the living room and tell my mom, “Dad disowned me. When I turn 18 I am legally changing my name to Price.”

“Okay..,” she said, from her green-blue rocking chair in front of the TV. Later I played her the voice mail my dad had left. She said she understood; she respected my choice and didn’t press it. Price was her birth name, the name of her parents and brothers. She took it well, and my maternal grandparents took it even better. My paternal grandparents were dead, so they couldn’t complain.

I’d been talking about doing it for some time by then. Bohannon was uncool and difficult, and it tied me to a man who was unpredictable and demanding. Price sounded right, icy and cool. It was easy to spell, reasonably common, and short.

Getting the name was a process that spanned several months. I held the name close for over a year, turning it over in my mind and my mouth, examining it, and cherishing it. I made it my Myspace name. People got confused — was I married? Had that always been my name? A few people forgot Bohannon altogether, including some high school teachers. I had to remind them all that the change wasn’t legal yet.

On my eighteenth birthday, I drove up to the State House in Cleveland with a copy of my birth certificate and social security card, plus a few forms and a check for $110. Changing your name in the state of Ohio requires a filing fee, some paperwork, and a formal announcement in a public paper read mostly by lawyers. If, after a period of two months, no one steps up to protest the name change, it is finalized. I made the announcement. I waited. My mother offered to go to the court house with me, but I declined, and showed up both times by myself in my debate team suits. By the end of high school, I was officially Erika Dawn Price.

Taken altogether, the name Erika Price has a wonderful balance. Five syllables each, ending and beginning with an E, the middle letters of both being RIC or RIK. The first word is a spiky, three-syllable climb up a jagged mountain; the second word a frosty slide down a cool hill. It sounded, someone told me, like the name of someone Batman would date. Someone else told me it sounded like a pop star. I think it’s a femme fatale name. It’s easy and memorable. I love it.

For a long time, the “Price” was my favorite name component, because I chose and paid for it myself. To me, it symbolized my own self-authorship and self-possession. I was not the property or branded descendant of a man who’d dismissed me. Taking my mother’s last name, I decided, was a principled and feminist act. An assertion of independence. I knew I would never change my name for anyone.

Perhaps because of all this, I disdained women who took their husband’s name, or who settled for the half-measure of a hyphen. As if that is a compromise, when it’s only the women who does it. As if it’s fair-and-square for the woman to half sublimate herself while her husband doesn’t sublimate or change himself at all.

I know this is a judgmental, rigid position that strips married women of agency and choice, but I don’t care. The history of women taken men’s names is a history of property transactions, ownership, and lost agency; it doesn’t matter how strong the woman is that takes her husband’s surname. She is changing herself for him, and he’s not, and the history of it is anything but romantic. But you won’t catch me saying this to any married woman’s face. I know how bad it sounds.

PhD.

Nowadays, though, Price is not my primary source of pride. As of February 2014, my name has one final component. PhD. Or Dr, if you prefer the prefix. I have worked for this symbol for a long time. Even when I was in high school, even when I was still “Bohannon”, I knew I wanted to be a Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology. I took college classes and read books about applying to graduate school. I imagined my name on the door of a university office, or on laminated business cards. I imagined being called a bitch and then correcting my foe with, “Excuse me, it’s Doctor Bitch.”

Now that my name is on a door, with the afterthought of a PhD printed behind it, I feel ambivalence. There are very few achievements in life that earn you a new name. I’m proud I met my goal, but demanding that people refer to me with a new honorific because of it just seems silly.

So I worked on a body of independent research for five years, big deal! Think of the grander projects other people have worked on without ever earning a new name for it. Sculptors and construction workers and architects and musicians and filmmakers and parents. You can work a thousand percent harder than me, and for ten times as long, and never get a new name to show for it. Why do I deserve a few extra letters? Am I changed forever by my choices? Isn’t everyone?

Erikadprice.

Because of my history, and because I’m introspective and self-absorbed, I put a lot of importance on the naming of things. I see my name as powerful emblem of selfhood. But like any sense of self, it is tenuous, mostly organic, and a little arbitrary. Half of it is an accident beyond my control, gifted to me by parents with fairly random preferences and intentions. The other half of my name may have been chosen or earned, sure, but all of it was plucked from nearby external sources. I didn’t invent any of it. I was never the author of my name, not really.

But, by living with my name and using it so often and for so long, I have formed a strong attachment to it. I have affection for it because it follows me around everywhere and stands for me. It speaks for me. When uttered or read, it summons some aspects of me in other people’s imaginations. And I have woven a somewhat complex narrative around that name, interpreted it, and formed a greater mythology from it.

Which is all that a self is, really. A semblance of unity around many disparate, random, and ultimately meaningless parts. Still, we’ve all got to have one. We all must have names. We all must form a sense of self from a smattering of thoughts and body parts. We never own it. We never deserve credit for it. But it’s ours just the same.

Originally published at erikadprice.tumblr.com.