Peer Review is Not Scientific

How a process designed to ensure scientific rigor is tainted by randomness, bias, and arbitrary delays.

How a process designed to ensure scientific rigor is tainted by randomness, bias, and arbitrary delays.

In my last essay, I discussed the ways in which the academic publishing process is unnecessarily slow, labor-intensive, and exploitative of researchers who are not paid for the research and writing they devote years of their lives to. Academic journal articles are mightily expensive to get access to ($35–55 for a single article, thousands of dollars for an annual subscription), and yet the people who collected the data, analyzed it, wrote it up, submitted it for publication, and revised it receive no compensation no matter how much money is spent accessing their work.

Today, I’d like to set my sights on another troublingly biased and sloppy aspect of the academic publishing process: Peer review. The peer-reviewed process, which is intended to boost the rigor and objectivity of scientific work, is not itself done in an objective, systematic, or scientific way. In fact, it’s one of the most scattershot, inconsistent messes possible.

The process of selecting and assigning reviewers is unsystematic and filled with room for bias and error; review processes themselves are not standardized in any way; the content of reviews is often arbitrary and influenced by personal agendas; it takes a miserably long time to conduct a review; and worst of all, no one involved in the process earns a cent.

…

The first thing I want all lovers of science to know is this: peer-reviewers are not paid. When you are contacted by a journal editor and asked to conduct a review, there is no discussion of payment, because no payment is available. Ever. Furthermore, peer reviewing is not associated in any direct way with the actual job of being a professor or researcher. The person asking you to conduct a peer review is not your supervisor or the chair of your department, in nearly any circumstance. Your employer does not keep track of how many peer reviews you conduct and reward you appropriately.

Instead, you’re asked by journal editors, via email, on a voluntary basis. And it’s up to you, as a busy faculty member, graduate student, post-doc, or adjunct, to decide whether to say yes or not.

The process is typically anonymized, and tends to be relatively thankless — no one except the editor who has asked you to conduct the review will know that you were involved in the process. There is no quota of reviews a faculty member is expected to provide. Providing a review cannot really be placed on your resume or CV in any meaningful way.

The journal article you have reviewed, if it gets published, may be placed in an immensely expensive journal, and your hard work may have helped the journal maintain its reputation as respectable and rigorous, but you aren’t gonna see a cent of that money regardless, and you’re not going to get any accolades for doing that free labor, either. Like many informal academic responsibilities, such as serving on committees or mentoring students, you are expected to do it for the love of doing it –while also juggling the responsibilities you are actually evaluated on.

…

Why does a researcher get asked to provide a peer review? Usually because they have published research in the topic area before. This makes sense, of course. You want reviewers to be people who are well-versed in a subject, who know its terminology and the theories that undergird it, who have some passing familiarity, at least, with the current gaps in the literature and any ongoing debates.

The problem is, the process of identifying and contacting a reviewer is not systematic. Not everyone who has conducted work in a topic area is asked to review. Someone who has published a ton of work in journal A (but not in journal B) may never be asked to provide a peer-review on a publication in journal B, no matter how relevant it is to their work. If an editor hasn’t heard of a person, or has never met them in person, they may not consider them to be a viable peer reviewer. Reviewers who are a good fit may not have the time to actually conduct a review.

As a result, who gets contacted first, who actually has the time to do a review, and who actually ends up providing the review has a lot of arbitrary elements to it. And often, the people providing reviews are graduate students, post-docs, and others who are lower in the academic hierarchy — because they haven’t learned to say “no” to unpaid, thankless jobs yet.

If you’re a busy professor with tenure, it’s likely you have no time, and no motivation, to complete a peer review. You’re busy teaching classes, grading papers, attending committee meetings, and mentoring graduate students of your own — that all requires a lot of reading, and thinking, and writing feedback, and sending emails. The last thing you want to do is get bleary-eyed looking over some additional half-formed research draft that it isn’t a requirement of your job for you to look at.

And if you have a nice, tenure-track academic job, you get very little out of providing a peer review, besides a pat on the back for helping the community, and maybe the chance to criticize a peer whose work you disagree with.

…

Conversely, if you’re a grad student, a postdoc, or a new professor, you probably feel like you are obligated to peer review manuscripts when asked, because you think it’s going to help establish you and help your career in some way. Though it probably won’t. You may feel, the first few times that you are asked, that being asked is an immense honor. It isn’t. You might even believe that providing a high-quality review will help you establish yourself in your subfield. That won’t happen.

Reviewers, as I’ve already mentioned, are largely anonymous. Only the editor who has asked you to do a review will know that you’ve put in the work. They might be grateful to you for doing them a solid, but unless you forge a real bond with them, it’s probably not consequential. Your university won’t know you’ve provided a peer review. Other researchers in your subfield won’t have any idea. Your peers or classmates won’t know. Your mentor will not be impressed.

Even if you tell people about the work you’ve been peer reviewing, they won’t exactly be impressed. Providing peer reviews is seen as necessary, but unimpressive, like going to conferences and providing service. It’s a thankless task that aspiring faculty are nonetheless pressured to take part in. And, like going to conferences and serving on committees, it ends up eating a lot of time and resources while remaining unpaid, unremarked upon, and unrewarded.

…

If you’re a high profile researcher in your field, you’ll tend to get more review requests. Because of the volume of requests, and because doing reviews is tiring and useless, you can’t take them all on. So you turn down the review requests, and they trickle down to your grad students or to less-established researchers who are jockeying to prove they are productive by any means necessary, including means that don’t actually help.

Since nobody is required to do a specific number of reviews, or any reviews at all, and there’s no payment for the service, the work of peer reviewing is doled out in an illogical way, one that is definitely not merit-based. One article may, by random chance, be assigned to two well-known, well-established reviewers who happened to feel like giving back to the scientific community on the day that the editor asked them; another article on the exact same topic may be assigned to two graduate students who have never reviewed an article before. Editors try their damndest to select strong reviewers, with a variety of backgrounds, but given there is no financial or professional incentive for the work, doing so is a major swim upstream.

…

Having established that the process of selecting reviewers is scattershot & not at all systematic, let’s talk about the process of review itself.

It’s also not at all objective. There is no training in how to do it well. Educators have known for a long time that giving consistent, useful feedback on a piece of writing often requires using a rubric or some standard marking scheme. Researchers have known for decades that if you want to consistently analyze human performance, you need training and practice in doing so.

Despite this, there is no rubric for the peer review process. A reviewer’s process and performance is not evaluated or examined for consistency and rigor. Reviewers are not trained. There are no mutually agreed upon professional standards that are used to assess the work’s quality. In my field, social psychology, a field that is plagued with questionable research practices, we don’t even have rules in place for how to make sure a study is legitimate. We do have some navel-gazey journal articles that muse on the subject, though.

So what actually happens, then, when an article is submitted to reviewers? Basically, you are subjected to the whims of the reviewers you have arbitrarily been assigned. You have no idea what to expect from them, going into the process. Who knows what agendas, pet peeves, & writing style preferences your reviewers are gonna have. Who knows how much time they’re going to put into reading your work, or how competent they actually are. You don’t even know who they are. You just know they’ve probably been published in the journal before.

…

The level of scrutiny that an article is subjected to all comes down to chance. If you’re assigned a reviewer who created a theory that opposes your own theory, your work is likely to be picked apart. The reviewer will look very closely for flaws and take issue with everything that they can. This is not inherently a bad thing — research should be closely reviewed — but it’s not unbiased either.

Your reviewer, if they have an ax to grind, may not search for flaws for the sake of science, but for the sake of their own career. And they may go far, far easier on a researcher whom they like or have collaborated with in the past. Scientists are humans. We fall prey to the same cognitive biases as the people we study, and we’re pretty un-self-reflective about that. And making sure a reviewer is appropriately strident in their critiques is not usually the journal editor’s job.

In addition to ax-grinding reviewers and dispositionally friendly reviewers, there are reviewers who don’t give a shit. These are typically overwhelmed people, or folks who are in over their heads. Either because of workload demands or a lack of experience and training, they cannot provide a useful review on the literature they’ve been given. They may delay providing feedback, or only make a few surface level comments that are not particularly useful. Or, in an attempt to appear helpful and critical, they may make a ton of irrelevant recommendations that delay publication, but don’t improve the quality of the work.

…

Many of the comments you do get from reviewers, no matter who they are, will be unsubstantive or subjective. A person may ask you to cite their own work more. Someone who prefers “myriads of” to “a myriad of” may criticize your grammar even though both usages are technically fine. A reviewer who doesn’t believe sexism exists may ask the author to remove language acknowledging pretty basic, well-established social justice issues. A reviewer who has a favorite pet statistical technique, or pet peeve, may ask for additional analyses to satisfy their own neuroses.

A lot of times, reviewers approach a paper by asking, “How would I have done this?” rather than “Was this done well?”. This leads to a lot of recommendations that come down to taste and tradition. And this is how problematic analytical processes (like p-hacking) get passed down from generation to generation.

A lot of reviewers, especially rookies, feel the need to prove that they have put a lot of work into the review, so they make a ton of recommendations pretty much just for the sake of recommending something. Authors may be asked to add collect several studies’ worth of new data, or they may be told to add a large section to their literature review, citing work that is related to the reviewer’s own work. Structural changes to the paper may be requested, to appeal to one reviewer’s personal preferences or biases. Sometimes these changes improve the paper as a whole, but often they just delay everything unnecessarily.

…

The peer-review process is also, unfortunately, subjected to all kinds of other human biases, including sexism and nepotism. While reviewers’ names are usually masked, author’s names are not always anonymous to the reviewers themselves, allowing for implicit assumptions about the authors to creep in. Cordelia Fine famously reported, in her book Delusions of Gender, about a trans male researcher who was perceived as more intelligent and capable by his colleagues once he started using a male name. He even heard people off-handedly mentioning that he was a “much better researcher” than his “sister”. He had no sister — people were talking about his pre-transition self.

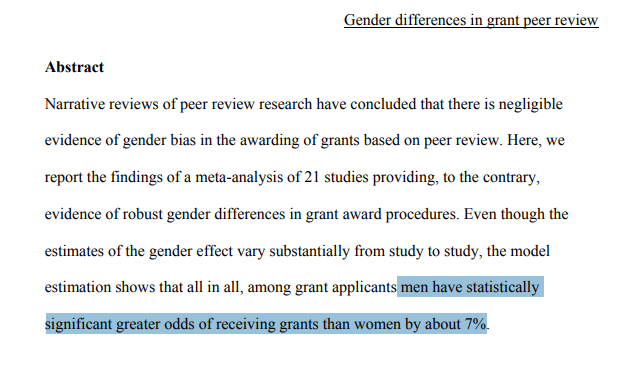

Of course, that instance is anecdotal. But the data suggests widespread sexism biases the peer-review process, too. Wennerås and Wold conducted a large-scale review of postdoctoral fellowship applications in 2010, and found evidence of sexism and nepotism. Women were far less likely to receive a fellowship, compared to men; when applicants were close friends with reviewers, they were far more likely to be accepted. In a meta-analytic study published in 2007, Bornmann and colleagues found that, under a peer-review process, “men have statistically significant greater odds of receiving grants than women by about 7%.”

I was unable to find published, empirical work establishing whether or not the peer review process is poisoned by racism. However, reviewers can often discern (or guess at) an author’s race or ethnicity based on their name, and prior work has established that when a name on a job application or resume is perceived as a “black” name, the applicant is more closely scrutinized and less likely to be selected. It is highly likely the same process occurs when a reviewer knows the names of article authors as well.

Of course, even when an author’s name is hidden from reviewers, there is still room for bias and prejudice to seep in. Work on racism, sexism, ableism, or any other structural form of oppression may be more strictly reviewed by a white, cis male author who is uncomfortable being reminded that the world is not a fair place.

If you’ve ever attended a research presentation in the social sciences, you’ve witnessed a well-off, established white male researcher attempt to pick apart the work of a black or female colleague, not on the basis of merit, but because he doesn’t believe the world is as bigoted as black and female people say it is. Scientists love to believe they are unflinchingly logical, which can make it even harder for them to acknowledge their own biases than it is for the average person.

…

Did I mention that it may take a reviewer months to return a draft with feedback? That some reviewers take upwards of a year? And that editors often have to remind, cajole, and harass their reviewers into getting a review back, even then? An author may be stuck waiting for semesters to hear back about an article, only to have their reviewer hastily read the work in a day and type together some surface-level critiques, based on subjectivities, and send them off to the editor without a second thought.

The slowness of this process is clearly related to the fact that reviewers are not paid, and are not assigned review duties as part of their official jobs. It’s a whole separate, unmeasured thing. Of course it’s gonna be a low priority when you have classes to teach, manuscripts of your own to write, and job talks to attend.

…

This is all worsened by the fact that academic journals do not allow simultaneous submissions. You can only submit a paper to one journal at a time. So you’re truly at the behest of 2–3 random reviewers, plus a journal editor, for months or years at a time, before your work can be seen. If it gets accepted the first time. Which statistically speaking, it probably won’t.

Most submissions are not accepted. If you’re lucky, the editor will “desk reject” your work within a few days. This happens when an article is clearly not a good fit for the publication, or it’s so shot full of flaws that the editor can tell it won’t pass reviewer muster. Getting a desk reject saves time at least. It allows an author to make big revisions or submit to an entirely different journal, rather than waiting around for months only to get turned down anyway.

Even after a full review process, most articles get rejected. This is part of how journals establish that they are rigorous — a high rejection rate looks good. It implies thoroughness, albeit in a tail-wags-the-dog kind of way. Many suitable manuscripts are sacrificed at the altar of rigor. A small but “fortunate” subset, instead, gets the exhausting but slightly hopeful “revise and resubmit”.

…

A “revise and resubmit” is not a guarantee that an article will be accepted after revisions are made. It’s merely an opportunity for the author to respond to comments, make some adjustments, and try for acceptance into a journal once again.

Sometimes revisions are merely structural or theoretical. Sometimes an author is asked to re-analyze their data. But often, especially in the social sciences, a research is expected to go out and collect additional data, analyze it, write it up, and then send the new draft to the reviewers once again.

Regardless of how long revisions take, they will then be sent back to the reviewers and the editor, where they may languish, unread, for months at a time. Finally, the reviewer may return to the draft, at this point perhaps not even remembering their original feedback. The author will, in all likelihood, receive a second round of feedback that is just as fuzzy and subjective as the first round ways, many months or years after the original submission. And that’s if none of the original reviewers have dropped off the map / gotten too swamped to finish the review / died.

…

Things don’t always go poorly, of course. Sometimes, reviews are relatively quick (a month or two), revision requests make sense, and revised work is accepted. That has happened to me, and my colleagues, quite a few times. In instances like those, the peer review process is a lot better than nothing. But that does not mean that it is adequate, or logical, or systematic.

Because the process is secretive, hard, long, and tedious, it has the illusion of contributing value and rationality to scientific work. And because scientists are the ones conducting it, it is assumed to be a scientific practice. But in practice, it’s not much better than receiving a few random half-considered comments on a conference presentation from whomever happens to show up. And there’s no structure, training, or pay scale in place to make it better.

Peer review is not a scientific process. Scientists are only scientists when they are following the scientific method. When they are giving feedback to a colleague based on gut feelings, personal preferences, biases, and limited resources, they are just humans, and they’re as inconsistent and sloppy as anyone else.

…

This messy, slipshod process delays the public’s access to novel scientific work. It means that published work is not held to a consistently high, yet fair, standard. It results in the lay public having a great deal of faith in work that they assume has been carefully and thoroughly vetted, but which they cannot easily verify. And it also puts an immense amount of arbitrary barriers between researchers and their professional goals. Publications are necessary for a researcher to receive tenure, or to have a prayer of netting a competitive academic job. And yet the process of getting publications is barely related to a researcher’s productivity or merit at all.

But there are alternatives. In the realm of mathematics, for example, journal articles are seen as an inefficient and illogical method of sharing knowledge with colleagues and the public-at-large. Mathematical proofs are instead shared rapidly, and freely, among the handful of specialists who take an interest in it. And when work is well done, it speaks for itself. Either the proof is successful in establishing what the writer set out to establish…or it isn’t. There’s no need to introduce random barriers to make the process look more logical. The work is already logical.

In my next article in this series, I will discuss how the academic publishing process can be reformed, taking some inspiration from the mathematics world, as well as from the growing world of open science. I’m still actively researching these alternative options, and the writing other people have done on the subject. If you’re a researcher and you have insight into how the peer-review process can be reformed, or what ought to take its place, please join the conversation in the comments, by tweeting at me (@dr_eprice), or by writing an essay of your own.