The fantasy of perfect justice puts victims in danger.

TW: Sexual Assault, Stalking, Domestic Violence, Emotional Incest, Abuse

Justice is an almost superstitious concept. By doing harm to the doer of harm, or by taking something crucial away from them (such as freedom, money, time, or rights), a wrong is somehow redressed and society — or the victim — is somehow protected. How exactly a robbery or a physical assault is undone by taking away a person’s right to vote or move about freely has never exactly been clear to me, or to anyone who opposes the carceral justice system. But justice is sought, hungered for, demanded all the same. It is intuitively appealing. It feels necessary and right.

Justice is an old concept, one that like revenge can have a very primal heat behind it. Cries for justice come in moments of deep desperation, or in the face of a catastrophically huge inequity. Justice is painful, it costs something, it is weighty, it can be might y— but so often, it’s impossible, or it doesn’t really make things better, not really, because the harm that lies in the past can’t actually be undone.

There’s nothing wrong with a desire for justice in the face of inequality, especially on a broad societal scale. Social justice — rooted in the goal of dismantling millennia-old systems of unfairly distributing power, wealth, and rights — is a type of justice that has teeth and a heart. It is focused not on sequestering a criminal for the sake of knowing that the criminal is suffering; instead, it works to make it harder for people to aggress against and take advantage of one another in the first place.

So social justice movements are not really what I’m referring to when I say that justice is a misguided, superstitious goal. When I say that, I’m talking about justice on a much smaller scale. Criminal justice. Transformative and restorative justice for victims of things like domestic violence or sexual assault. I am not sure that meaningful justice is possible for survivors of such crimes, and furthermore I’m fairly convinced at this point that justice ought not be the primary goal for the victim or for society at large.

It might seem odd to hear this coming from me, a multiple-times survivor of sexual assault, stalking, and domestic abuse. I am also someone who has written whole-heartedly about wishing that my abuser were dead. I’ve written that I’m glad David Foster Wallace is dead, because that means he cannot victimize anyone else. I’m deeply familiar with the white-hot urge to make the ones who dole out pain feel their fair share of it. No one is more angry at the rapists, stalkers, and harassers of the world than me.

Justice, revenge, pain delivered as payment for past pain — I resonate deeply with the desire for these things. I have been victimized by a variety of people, and I have known, loved, and worked to protect numerous other survivors, too. And from those experiences, I’ve come to believe that justice can never be a victim’s primary goal. The most a victim can hope for, usually, is that they put thousands of miles between themselves and their abuser, and that their abuser is never brought into their life ever, ever again.

Safety is paramount. Justice is usually impossible. And often, the pursuit of one threatens the attainment of the other.

…

Let me give you a bit of personal background. I have been abused by a handful of people, mostly men, over the course of my life. I have never seen any of them pay for their crimes in any kind of meaningful way. The legal justice system has never helped me. Restorative/transformative/community justice efforts have never helped me. I’ve never really achieved any form of satisfying justice at all. I have only enjoyed the safety provided by distance from my abusers. Sometimes, that distance has come in the form of death.

The first abusive person in my life was my dad. I don’t think he was malicious, just troubled. He said inappropriate things to me constantly. Sexual things. Overly personal, difficult-to-process facts about his life and marriage. Evaluations of my body and my appearance. Insults about my ability level or behavior. Rageful rants. Musings about suicidal urges that he felt. Paranoid screeds about the wrongdoings of other people. He offloaded all his emotional and psychosexual burdens onto me, and as a child I had no choice but to hold them.

I don’t think he meant to terrify or torture me with all the nonsense and vitriol that sprayed endlessly from his mouth. But he did. It left me emotionally drained and vulnerable. It made me self-effacing, conflict averse, soul-sick. When I was 16, I was stuck on an seemingly endless phone call with him, in which he ranted and used me as an emotional diaper, and for some reason I reached a breaking point. I pulled the phone away from my ear. Let him chatter until he was satisfied. Hung up. Never talked to him again.

When I stopped calling him, and refused to continue seeing him, he became explicitly threatening and abusive. He left me angry voicemails. Disowned me. He began to neglect a chronic health condition. A few years later, he died.

I lived with guilt over my dad’s death for many years, certain that I was to blame for the isolation and untreated illness that overtook him in the years after we stopped speaking. I realize now, over a decade later, that detaching from him and leaving him to die was the only way I could protect myself. If I had remained in contact with him, he would have remained an emotionally vampiric, sexually inappropriate, capriciously abusive presence in my life. And then he would have still died anyway.

There was no hope of justice for me. There was no hope of mending fences. There was only distance, time, and death to keep me safe.

…

I was in a physically, sexually, and emotionally abusive relationship with NS from 2009 to 2011. That doesn’t sound like a very long period of time to me, these days. But the damage stretched on for years after the relationship was over, and some of the trauma responses still get rekindled now and again, when a man raises his voice near me, or certain sex acts are brought up in casual conversation. The way NS treated me was monstrous, and I was changed in fundamental ways by it.

Breaking up with NS took several tries. On average, it takes a domestic violence victim seven attempts to leave their abuser successfully, and each attempt puts them at an elevated risk of being murdered. In my case, I had to wait until NS was out of town, in a remote area hundreds of miles away from me. I broke the news via email. And then I stopped talking to him.

NS tried everything to get me back into his thrall. He left presents under my desk at work. He wrote me long, meandering emails filled with stories about the two of us. In some of the stories, we got back together and loved one another forever. In some of the stories, I died. He showed up outside my apartment, baying like a banshee. He went to my boyfriend’s show, and posted about it on Instagram, hoping I’d see it and take it as an implicit threat. He broke into my apartment building, and banged on the door until I threatened to call the cops. He lingered around the edges of my life and would not go away.

Eventually he got arrested — for something else. I doubt very much that he would have gotten arrested or charged if I reported any of the things he did to me. Domestic violence and sexual assault cases so rarely play out well for the victim. I certainly wasn’t interested in igniting his fury by attempting to get legal justice. I also didn’t attempt to report him to the graduate school in which we were both enrolled. I knew it would be best to keep my head down, let him graduate, do as little as possible to provoke him.

NS getting arrested did have some tangible benefits for me, however. He was on house arrest for a while, after spending a week or so in jail. That kept me safe. Until it didn’t. Once he was free to roam the city, he started darkening the doorways of my life again. Demanding conversation, coffee dates, my encouragement for his Master’s thesis defense.

Ultimately, NS never faced justice or retribution for the myriad things he did to me. And he didn’t leave me alone because of any system of justice or victim advocacy. He simply moved away. Getting arrested had been kind of traumatic for him, he said. He needed to get out of town, start fresh, find new victims in a place where he hadn’t already alienated dozens and dozens of people. And it was that fleeing that kept me safe.

In the intervening years, NS has victimized many more people. Justice is not what any of his victims can hope for. He has been to court numerous times for a variety of physical altercations and instances of abuse. He remains a white man from a wealthy family, and he keeps slipping out of justice’s grasp. In the rare instances where he has been charged with a crime, he’s been given a light sentence and then swiftly released back into the world.

The damage he has done will never be undone. Every attempt at making him pay for his crimes has come up short, and will continue to come up short. I have long ago abandoned the desire to see him meet justice. I want only for him to get as far away from me and his other victims as possible. I hope that someday soon that our safety is assured by his death.

…

At some point, I became known as a person that other victims could reach out to for support and validation. So I’ve heard a lot of abuse and assault stories. None of them play out like an SVU episode. There is never a cunning, yet compassionate cop who believes the survivor, nor is there ever a canny attorney who marshals sufficient evidence to put the assailant behind bars. Hell, there’s rarely even a supervisor who gives enough of a shit to stop scheduling the victim for work shifts alongside their attacker.

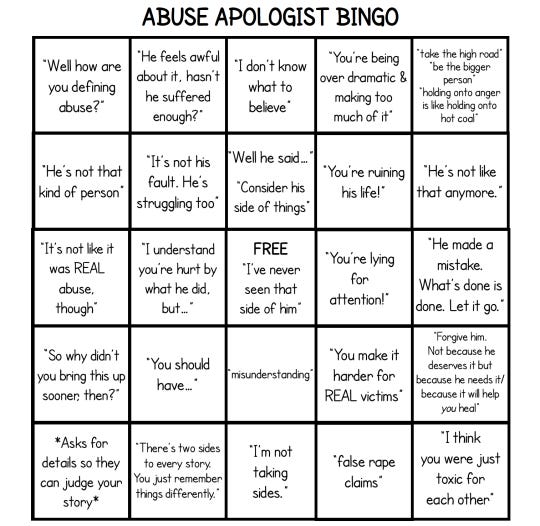

Even in the #MeToo era, most people will not believe a victim if it requires a modicum of inconvenience. Self-identified feminists are happy to devour abuse narratives and chirp platitudes of support in a victim’s direction, but they blanch when asked to banish an abuser from their social midst. If the possibility of justice or consequences is raised, people get squirrely and start talking about proof, and investigations, and how awful it would be to ruin some poor man’s life.

Everybody wants to be the victim’s cheerleader; no one wants to be the executioner. Even if the ‘execution’ is just telling a dude that he can’t live in the polyamorous hippie house anymore. Or that he’s not invited to an open mic. Or that he has to leave the bar after he’s already screamed in a woman’s face.

The truth is, in nearly all instances of assault and abuse, third parties will never have access to an objective recording of exactly what went down. When faced with ambiguity, a choice must be made. And when people elect to remain neutral or to stave off judgment in the pursuit of an objective truth that will never arrive, they are protecting the safety of the accused, and forcing the victim to flee. That’s how it plays out. Like it or not. A non-choice is also a choice. And usually, people would rather do that than pursue meaningful justice or safety.

…

Unfortunately, the one common alternative to the do-nothing approach, at least in leftist circles, is to engage in an attempt at restorative or transformative justice. Compared to the ‘justice’ metered out by the state, restorative justice certainly sounds appealing. No one gets locked away or used as slave labor. Peace can be brokered from within the affected community. Damaged relationships can be repaired. In theory, that is how it works.

In practice, the language and tools of restorative justice can very easily be leveraged by an abuser, and used to undermine and control their victim. Restorative justice, as it is often practiced, requires a victim meet or engage with the person who harmed them, and collaborate with them in some way to return the community to a state of relative harmony. What is being ‘restored’ is rarely safety or fairness, but rather the social ease of the community that has been inconvenienced by visible harassment and abuse.

Restorative justice often keeps people tangled up in one another’s affairs when they ought not to be. As I’ve already outline above, it is usually vital that a victim get miles and miles away from the person who harmed them. Attempts at brokering a meaningful, transformative ‘justice’ between the victim and the abuser prevents that.

I want to be clear about this. I do not believe in the United States’ criminal justice system. I believe it is irrevocably biased, and that the ‘justice’ it provides is dehumanizing and torturous. I do not believe that the solution to virtually any crime is to arrest someone and take all their freedoms and comforts away. Imprisoning and mistreating human beings does not undo the traumas and wrongs of the past. And as I’ve already discussed at length, legal attempts at justice rarely provide any solace or safety to an abuser’s living victims. I also believe that restorative and transformative justice are a good fit for dealing with some forms of conflict and wrongdoing.

However, when it comes to crimes of abuse and assault, restorative justice is rarely a useful approach. Abusers and rapists are, typically, very adept at manipulating people and feigning regret. They groom friends and character witnesses just as readily as they groom victims.

NS, my abuser, knew all the language and concepts of social justice movements, and he knew how to look mournful and repentant for his deeds. He could write a killer apology. I fell for it dozens of times. In a restorative justice process, he would have gamed dozens of people into believing that he was redeemed and that I was just bitter and crazy and needed to ‘get over’ what he had done.

It is perilously difficult to tell the difference between a genuinely remorseful former abuser and a self-protective monster trying to game the system to his advantage. And when a community prioritizes resolving a conflict over keeping a victim safe, they unwittingly force a victim to brush their pain and terror under the rug, or risk being ostracized themselves.

Some relationships cannot be restored or transformed. Some social ties must be frayed. True supporters of victims must be willing to make hard choices. And that choice must prioritize the victim’s safety over the superficially warm feelings of conflict resolution.

This is a very bitter pill for a lot of prison abolitionists to swallow. It was hard for me to come to accept, too. But my experience as both a victim and an advocate for victims has taught me that practical, immediate safety from further physical harm is vastly more important than a forced pantomime of peace and harmony.

…

If you haven’t survived prolonged abuse, this essay probably strikes you as bleak and dispiriting. Most people want to believe that damage can be mended, estrangements can be repaired, and people who have done evil deeds can change for the better.

And technically, yes, all those things are possible. People can change. Healing can happen. Sometimes, two parties in conflict can reach a state of peace. The problem is, the victim and the victim’s community is never in control of whether that happens.

An abusive, manipulative, malicious person can only change if they are truly, internally motivated to do so. External consequences cannot make it happen. Peer mediation cannot make that happen. No amount of forgiveness or courage on the part of the victim can make it happen.

The victim and the community lack the power to force an abuser to change. In the absence of such power, neither the victim nor the victim’s community should be working to improve their relationship with the person who did harm. All they should be focusing on is limiting the potential for future harm. This is accomplished by isolating the abuser from the victim, as well as from potential future victims.

I get the desire for justice. We all want the traumas of the past to be undone. But they cannot be. Instead, they must be believed in, lived with, and acted upon. Often the only way to act upon unforgivable evil is to refuse to forgive or forget, and to push an evil-doer as far into society’s margins as possible.

The real reason that I yearn for my abusive ex to die is not because death would provide him some karmic comeuppance for his crimes. His death would not take my pain away. I want him to die because then I, and all his victims — past, present, and potential — would truly and permanently be safe. There is no perfect solution to abuse. There is only freedom from future harm.