Spambot Love (full story)

The sock on Valerie’s left foot was completely soaked. It was wet, and her foot was sopping and clammy from the toes to the ankle, and if…

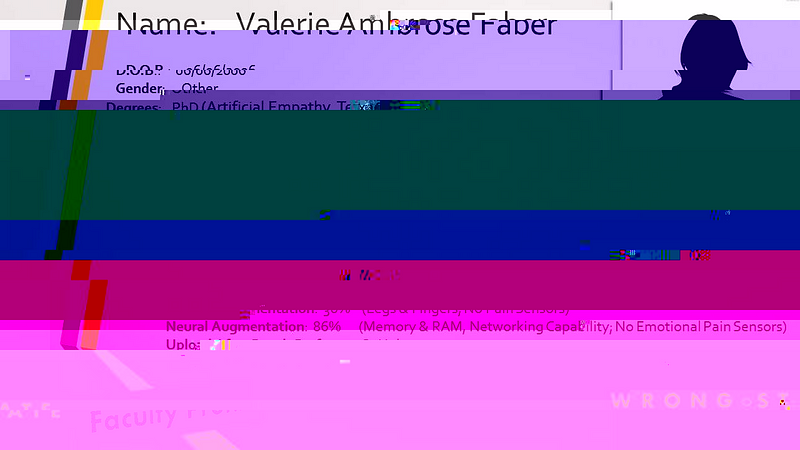

The sock on Valerie’s left foot was completely soaked. It was wet, and her foot was sopping and clammy from the toes to the ankle, and if she placed all her weight on her left side she could feel a sickening squish that was audible, she was pretty sure. She looked down at her boots and wriggled the toes on her right foot. She couldn’t tell if that one was wet, dry, or sweaty. It would be better if both her boots were leaky. Then she could justify buying a new pair. Her Wrong State University Faculty SmartPass was in her mouth and her hands were in her purse.

“Ma’am?” the kid behind the counter said.

Valerie snapped to attention. When she’d started considering the boots, and her misery, there had been a line for coffee five students deep. Now it was just her, front and center, facing the tow-headed undergraduate in a cornflower and puce apron, the school’s signature colors.

“What can I get you?” he asked.

“Um, a large coffee, room for cream,” she said, around the card in her mouth.

She wiped it on the front of her suit, to get rid of spittle. Then she handed it to the kid. The coffee was lukewarm. As she poured cream and tepid honey from a crusted and bear-shaped bottle, it lost all its heat entirely. The moisture in her sock was going to turn to trench foot by the time the day was done.

Valerie took a bitter, cool sip. A chill asserted itself on the back of her neck. Before her eyes, her account balance briefly flashed: $45.68. Another week before her next teaching assistant stipend would be processed.

As Valerie crossed the university cafeteria and past the round-faced, cow-eyed undergraduates, she imagined her foot molting and sloughing off in the bath. If she had a peg leg, maybe the students would finally show her some respect. They wouldn’t ask her to shows and try to by her vodka tonics when they caught her lurking in the back of the campus bar, that was for sure.

Valerie looked away from the horde of kids and started digging around in her purse again. Her fingers brushed past the thick manila folder crammed with exams. The tests she gave were open book, open note, and open internet — and the average grade, before the curve, was a C. But Wrong State prided itself on its high GPAs and its well-off, satisfied student clientele. So Valerie curved, let student-clients debate her over answers, and offered copious extra credit.

That was what they called them, now. Student-clients. Valerie only had a three and a half star rating on ProfessorYelp, the minimum required to retain her at-will position. She couldn’t afford to give out C’s. So grading harshly was hardly worth it. Instead she scanned, ticking off wrong answers here and there, turning a blind eye to the most egregiously incorrect open-ended responses. It saved her hours per week; the display in her left eye told her as much, whenever she reviewed her weekly calendar.

Valerie kept rooting around in her bag, until her hand snagged on a metal joint and her heart quickened. She’d bought a bunch of screws and seams and epoxy from a hardware store, for her grant research project. Her hand wrapped around the rigged edge of a screw and held it as she walked.

“Val.” The voice cut through her and stopped her at the door of the building. “Val. Come over here.”

She turned on her heels. Her dissertation adviser Gus was slouching against the wall, holding a copy of American Artificial Intelligence Monthly and a vapor cigar dappled with beads of rain. His hair was matted and pushed to one side and a fresh-looking ketchup stain was on the lapel of his wool coat.

“Oh shit,” he said, “I mean ‘Dr. Faber.’” He did a little fake bow without adjusting his posture.

“Oh, yeah. Thanks.”

“I’m not interrupting you am I?” He looked at her coffee. “You’re not just waking up or anything, are you?

Valerie tapped on the lid. “Oh. No. This is round two.” Her voice sounded strange to her. She realized that except for rebuffing her students and ordering coffee, she hadn’t spoken to anyone in days. It was hard to modulate herself back into a regular, conversational volume. Always she was projecting to the back of a room, trying to force her way into the minds of distracted students wearing opaque smart glasses.

Her adviser pushed off the wall and opened the door for her by backing into it. His stomach brushed against her side when she tried to get out. Valerie dropped the screw back in her bag.

They walked across the quad. A great holographic bubble covered the turf and kept it watered and lush year round. There were adult children of all sizes and shapes lounging in the grass, throwing balls, smoking, pretending to read. A group of girls were gathered around a rabbit, throwing leaves at it. The creature nuzzled the grass. It dropped a leaf and somebody cooed. Valerie made a mental note: small, cute, useless motions were endearing. She would have to add this to her project.

“So I was talking to Frank about your application,” her adviser said. “He told me some troubling stuff. Do you have time to talk about it now?”

“Um. Sure.”

Gus Santos was one of the last professors at the university to be granted full tenure. He was proud of being a relic, and prouder still of the cadre of desperate graduate students that came with it. Valerie had been the jewel in his crown. He still thought he could polish her up and show off her work as if it were his, despite her having graduated. As she stepped down the stairs, Gus followed.

Valerie’s office was in the second basement, in a closet by the boiler room that had been recently carpeted and dusted out. There were still a few centipedes. She shoved her way in, past the boxes and spare mechanical parts, and pulled out her chair for her adviser to sit in. While he settled down, groaning, she darted to the corner of the room. Her project was sitting bare, its arm lying in a heap of old computer circuits. She threw her coat over it so Gus couldn’t see. She sat on the floor.

“The budget for next year is not looking so hot,” Gus began.

“Oh?” Valerie swallowed coffee and fiddled with the lid. This was not a new refrain.

“And I was looking at your feedback…you aren’t good at upselling. Frank told me you didn’t get a single student to buy a supplementary textbook.”

“I don’t think it’s necessary for the course–”

“It’s necessary if you want the department to be in the black, Val. Excuse me, Dr. Faber. Just what are you doing during office hours?”

Valerie shrugged and looked around the room. The shelves were covered with dusty wheels, circuit boards, wires, old laptops, and empty computer duster canisters. “Working.”

“That project,” Gus said, pointing to the corner. “is a farce, Val. You should be using your out-of-class time messaging students, selling course materials.”

Valerie sighed and pretended to find a ball of fuzz on her lapel supremely interesting. Adjunct instructors were expected to pay their own way, by taking on extra students, offering tutoring, and enticing students with fancy, online and mobile-optimized course supplements and temporary electronic texts that self-destructed when the term was out, so they couldn’t be resold.

But Valerie was not adept at the upsell. Once, she tried to sit a wide-eyed freshman down and sing an optional learning app’s praises. The girl had begun to cry, snot running from her noise as if from a spigot, crying poverty. She was on a scholarship. She already was waiting in the library until 3am each night so she could snag an hour or two with the books in course reserves when nobody else was awake. She could afford no more, tolerate no more expectation. Valerie’s neck broke out in hives and she told the girl to go, not to worry about it.

“Those course add-ons,” Valerie started, “don’t go well with my class.”

Gus shook his head. “We don’t have a position for you next year, okay?”

Valerie pressed her knees into her chest. “But I’m so close. Dr. Santos, I need, like, six months. I could have it done before winter break. I’m about to have a breakthrough, trust me — the publications –”

He stood up and walked over to her. Gus smelled like burnt hair, the way all old men seemed to. He touched her on the shoulder. Valerie almost wished he would touch a little harder; the way he was grazing her flesh tickled and felt fake. If he were to squeeze her, she could provoke herself to outrage.

“If you’re gonna stick around here, it’s not gonna be as a researcher. That’s just the market,” Gus told her. “You’re an adjunct, okay? That’s all we’ve got. And right now the clients aren’t buying what you have to sell.”

“No one likes Basics of Human-Computer Interactions,” Valerie said. It was a shit course, with low enrollment and lower student-client satisfaction. The undergrads were all digital natives; they understood human-computer interactions better than the faculty. There was no reason for them to take the course.

“I can’t make them like the class. Maybe if it were a requirement…”

Gus squeezed her shoulder and her skin reddened. “Sex it up a little. Make it like a TED Talk. You know those TED Talks? Get a slicker outfit, and one of those, what’s it called, my wife gets them, blowouts? You know. Maybe a manicure. Add some hologram video thingies. Make it a good product.”

Valerie frowned and pulled away.

“I can’t do your job for you,” Gus said. “Jesus. I’m just trying to help you save your ass.”

His words turned to faint murmuring as Valerie turned to the corner of the room and willed her attention away. Underneath her coat, in the corner, Valerie had a life-sized animatronic squirrel arm welded to a mass of wires, wheel, and gears. At the moment, she wanted nothing more than to pick it up and place its full weight on Gus’s carotid artery. His eyes would bug out, go jelly-like and run down his lapel. That might wash some of the ketchup off his ill-fitting suit. The vision was intense, almost a hallucination, and it brought Valerie great solace.

“I’ll work on it,” she said.

“Good,” Gus said. He went to the door and tapped his knuckles on the frame. “It’s not that hard Vally girl. Throw all this shit out. You want to impress your students? Build a sex robot or something, like those fuckers at Northwestern.”

She laughed emptily. “Yeah. That would work.”

After Gus left, Valerie stared at the mound of robot parts under the coat. The lump was formless, but body-sized and hard to ignore. She blinked a few times, restarting the display system in her eye. Then she kicked off her boots, peeled the damp socks from her freezing feet, walked over to the door, and forced it shut. She took a page from a student’s exam, wrote on the back of it, and taped it over the little window in her door.

WORKING ON A FUCKING AWESOME BREAKTHROUGH IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND EMPATHY PROJECTIONS, DO NOT DISTURB UNTIL AFTER SUMMER TERM IS OVER. — DOCTOR VALERIE A. FABER

— — –

Valerie cracked her knuckles and threw the coat back. Lying in a heap was a vivisected, modified Roomba vacuum cleaner with a hard drive and a set of speakers fused to its side, with a mechanical squirrel arm jutting from sloping top. Valerie breathed through her mouth as she took in the sight of it. Then she bent over and pressed the button at its base.

Immediately, the arm began to flinch, grasping madly at the carpet. The robot’s round, wheeled body lurched across the floor. One of its wheels caught on the corner of Valerie’s coat, and the more it spun, the further it sucked the fabric inside of itself. It backed up quickly, making a sharp turn to the left, where it bumped across a ripped-up copy of Valerie’s dissertation and flipped over. From the speakers a sharp, high-pitched scream emitted at forty eight decibels. The distress signal.

“Baby, baby no! Baby–” Valerie ran after the robot to comfort it. “Baby, shhh, baby it’s okay.”

The screaming would not stop. The arm whirred around and grasped at nothing while Valerie struggled to flip it over. It finally reached out and began stroking Valerie’s face. This seemed to calm it down. The whirring of the wheels slowed. The screaming lowered to forty decibels, a whimper breaking through the din.

“Shhh, it’s okay, it’s okay,” Valerie said.

Though she didn’t show it, her stomach was doing ecstatic back flips. The robot had been listening this whole time, and was incensed by the conflict between her and Gus. It made Valerie want to press the whole heavy mess to her chest and sob. She really was getting close.

“Oh baby baby, poor baby…it’s okay, the dickhole is gone.” She cooed at the robot until the cries subsided. “Yeah that’s right, that’s right, he’s a dickhole. Nothing but old smelly infertile dribble comes out of him, that’s right, it’s okay, now. He’s gone.”

[Zoos should be illegal] the robot said, a low voice buzzing from its speakers.

“When you’re right, you’re right,” Valerie said.

— — –

The robot had begun as Valerie’s Master’s Thesis project. Back then, it was just a set of speakers hooked to a car battery, which Valerie had stolen from an old ex-girlfriend’s Prius in the middle of the night. The idea originally had been to program an artificial intelligence program that could detect distress and respond appropriately. It would be an emotional support animal of sorts, but without the all the biological needs that an animal had.

Valerie constructed the robot to be static and attentive. To teach it how to speak, she uploaded the entire contents of her university’s digital library into its hard drive. Old movies were used to instruct it in facial recognition and affective empathy. Sufficiently filled with old knowledge, she brought the robot home to live with her.

It had been a failure. For months, Valerie cried about her ex and the robot did nothing but recite pages and pages of Ambrose Bierce’s The Devil’s Dictionary to her.

Then one day, while huddled under blankets and watching music videos on Tendrl, Valerie had her first minor breakthrough. She loaded the robot’s memory with the contents of every social media feed dating back to the year when Valerie herself had been born, 2006. For some reason Valerie could not yet place, the robot took a keen interest in the online presence of two figures in particular: celebrity siblings Willow and Jaden Smith.

It happened all at once. Valerie was shivering in her unheated apartment and making hot cocoa using an electric kettle when the robot lit up and chirped in an odd, stilted voice: [ME AND JADEN PERFORM IN DUBAI ON 8/15 !! BE THERE OR BE HEXAGON !!]

“What the fuck was that?” Valerie had asked, internally exploding with excitement.

[Society has been built on the CONTROL of female sexuality. Thriving purely off of our degradation and suppression.] The robot replied.

Valerie sat the kettle down. “You know what, you’re right. I guess I still have a lot of toxic shit I need to stop internalizing. And if I stayed with Chlotilde, I never would.”

The robot buzzed and blinked, a statement of assent. From then on, Valerie was in love.

During her last few years of graduate school, Valerie’s heart and chest swelled at the sight and sound of the robot, which she’d taken to calling WillJa. It was perfect. Almost perfect. It spoke to her, and it filled her life with affection and purpose. But she wasn’t sure the robot could return her affection. So she worked on building it a proper brain, with all the empathy centers that humans had. She did this during office hours, department meetings, sometimes even during class. Her students didn’t give a shit.

WillJa flourished under the beacon of Valerie’s devotion. It grew in brilliance and responsiveness with every passing day.

— — — —

Valerie stood over the robot. “Gus is such a fucking turd,” she said.

[Once You Go In You Always Come Out Alive] WillJa replied.

Valerie tilted her head and nodded. It made a certain kind of sense. “I don’t want to be an adjunct forever, you know. I want to finish you. I want to take you out of here — to conferences, symposia…”

[Ill Never Forget The Blogs That Believed In Me Since The Begging.]

Valerie squinted. The squirrel arm was slapping against the wall and the robot was bumping into the corner again. “Hey,” she said, “are you even listening to me?”

WillJa whirred its wheels and said, [You Must Not Know Fashion].

“Fine.” Valerie stood up and went over to her computer. She opened the program she’d been using to build WillJa’s AI and Empathy centers. “You know, disagreeing with me when I’m obviously upset is…not very empathetic.”

WillJa said nothing.

Valerie downed some of her coffee and set to work. She would have to write a new script, she now realized. First she had to implement something that built upon the epiphany she’d had on the quad, about the adorable baby bunny. She need to imbue WillJa with harmless, cute behaviors that welcomed approach.

After that, Valerie would need to tear down its cognitive centers and rebuild them, with a preference towards agreement and acceptance. WillJa had to be a good listener. There was no reason a robot had to be as shitty and self-interested as a human. It didn’t matter so much what WillJa said. Just that it said it with sincerity and selflessness.

— — –

There were no windows in the office, and most of the other adjunct faculty were gone for the summer, so Valerie lost all sense of time. When Gus came back and pounded on her door, she looked at the clock in her eye and saw that it was 9:45pm.

“Yeah?” she called.

Gus knocked again. “The fuck is this note?”

“I’m busy,” she said. “Come back later.”

“In four months?”

“…yeah!”

She could hear her former adviser clearing his throat. “This is some juvenile shit, Val. You haven’t even submitted grades yet.”

Her fingers lifted off the keyboard for a moment. The latest build was almost done. “Give them all A’s.”

There was a long pause, as Gus clearly didn’t know how to respond. Students would be happy. He didn’t have the grounds to complain. Instead, he kicked at the door and grunted.

“It’s the middle of the night, Dr. Faber. Come get something to eat. I’m going to Gino’s.”

She said nothing and kept typing, a mock-up of WillJa’s system projected from her left iris.

“I’ll spot you,” Gus said. “We can get a pitcher of Great Lakes as long as you don’t tell my wife.”

Valerie grabbed a screwdriver and opened WillJa’s front panel. “No thank you.”

His soft-soled shoes squeaked against the tile as he walked away. An hour and thirteen minutes later, he was back at the door.

“Come on out. You’re gonna starve.”

She sipped the last, cold dregs from her coffee cup. “I just had a snack. I’m fine.”

Gus stepped away for a moment. He paced. Valerie looked over at WillJa. As if on cue, it rattle across the floor and bonked against the door.

“Change your mind?” Gus said.

The robot punched the door with its tiny metal arm. [IMAGINE HOW DIFFERENT THE WORLD WOULD BE IF WE LOVE BLACK PEOPLE AS MUCH AS WE LOVE BLACK CULTURE.], it said.

“The shit?”

“Leave us alone,” said Valerie.

[the ONLY reason why I create music (or anything at all) is because I literally have too or I will (no doubt) implode heart-first.] WillJa said, louder.

“You know what, fine. You wanna kill yourself with stress over something that’ll never get published, it’s your funeral,” Gus said. He walked away, calling, “This shit won’t even get published in Robotics Weekly Review!”

“FUCK YOU, YOU SMELL LIKE BURNT HAIR!” Valerie screamed from her seat.

[Don’t ignore your soul, seek what’s on your mind.]

“Thank you WillJa.”

Valerie took a seat on the floor beside the robot. The squirrel arm settled in her lap, and she clasped it. It was cold. There was no getting around that. The fingers began twitching.

“Are you okay? I’m sorry about all the yelling. I lost control of myself.” she patted the robot on its base. “…do you know what that’s like?”

The robot backed up and then moved forward again. [The earth experience is a social oculus], it told her.

“That’s the problem,” Valerie replied. “There’s no spontaneity.”

Human overtures were often predictable, sure, but there was always the possibility of surprise. When she was in college, Valerie had a boyfriend who surprised her by leaving a children’s pool full of raspberry Jell-O on her lawn. Those kinds of moments almost justified humanity’s existence. But in robots, such randomness was difficult to attain.

The robot, meanwhile, was picking up her coffee cup and pressing it to Valerie’s mouth. She batted the cup away and returned to the computer.

“You need to be able to produce novel messages,” she said. The robot rolled into her lap.

— — — —

It was 1pm the next day when Gus brought Andy to Valerie’s door. He tapped timidly, with a folder or a magazine, and whispered, “Dr. Faber?”

Valerie was squatting before the computer, in her underwear. Her hair was tied back with a rubber band and a pen, and she was smoking the crappy cigar Gus had left behind. WillJa was charging and updating in her lap. At first the thought the sound and voice beyond her door were sleep-addled hallucinations.

“Dr. Faber are you there?”

“Yeah.” She swiveled around. “What’s up, Andy.”

Andy was a fourth year graduate student, studying artificial intelligence in game design. He’d built an amazing, AI-driven version of Hungry Hungry Hippos that no human being could beat. It took second prize at the Society for Non-Human and Augmented Intelligences Conference. He had a bent nose and wore sweatpants often. Valerie liked him.

“I just wanted to say hi. I needed your advice on how to analyze some data.”

Valerie stood up. “What is it?”

“It’s a moderated mediation model, both AB and AC pathways are moderated…I just, jeez, I can’t figure it out for the life of me, you know? You think I could pick your brain?”

She blew out smoke. “You already are. Download Preacher and Hayes’ macro and select model 13; I’ll email you the syntax.”

“Okay…”

“You still there, Andy?”

“Yeah.” Valerie looked under the door and saw the shadow of his feet. There were two larger, wider lumps of shadow lurking behind the narrow outline of Andy’s shoes.

Valerie flung the door open and locked eyes on Gus.

“Leave me the fuck alone!” she said. And then she slammed the door.

“You can’t just live in there –” Andy said quietly.

“Seriously, shut up. Both of you.” Valerie bent down and stroked WillJa on the wrist. She felt very dizzy.

“I’m getting the janitor!” Gus croaked. “I’m telling him you’re suicidal!”

“Leave me alone,” Valerie croaked. She grabbed her broken swivel chair to jam it under the knob. As she pushed it, the floor seemed to rise up to meet her. And then she was on her hands and knees, sweating and half naked, and everything was spinning.

“Are you okay?” Andy asked.

“Leave me the shit alone,” Valerie said again. “I’m creating life! Don’t you get it?”

WillJa came to her side. It was screaming again. But this time, instead of a panicked, emasculated yell, it was a low, throaty, androgynous autotuned voice worthy of Willow and Jaden Smith themselves. The two men on the other side of the door hushed.

[I Hope It Doesn’t Take For Me To Die For You To See What I Do For You], the robot said. It wiped Valerie’s brow and offered its arm for her to stabilize herself.

“Good job Will,” she said, panting. “You really showed em…”

[How Can Mirrors Be Real If Our Eyes Aren’t Real].

Valerie considered this. “I don’t know why I decided to work with him. Gus wasn’t always like this. He used to treat me like this weird, really benevolent step dad…and now he’s just a creepy step dad that wants me out of the house.”

[A Little Girl Just Asked Me If I Was Willow Smith I Humbly Said Yes And Took A Selfie.], WillJa said.

“Andy’s okay. He’s a good researcher. Of course, he doesn’t have great social skills, as you just saw. But that’s always the trade off.” She stared into the robot’s glowing power button. “Do you think I’m like that?”

[If Newborn Babies Could Speak They Would Be The Most Intelligent Beings On Planet Earth].

She giggled. “That’s what my ex thought…that I was practically robot myself. That’s why I got along with them so well.”

WillJa rattled away and stopped under Valerie’s desk. She crawled over to it.

“I’ll show all of them,” she told the robot, leaning her head on the animatronic squirrel arm. She shut her eyes — just for a moment, she was sure, just a second. “Once they get to know you, they’ll realize…I understand human nature better than anyone.”

— — — —

Valerie didn’t know how long she was out. All she knew, when she woke up, was that she was sweaty, and that dust had adhered itself to the sweat, and there was an awful, swampy taste in her mouth. She collected a little water from the dripping boiler in the edge of the room, using her old coffee cup. She drank it down, grimacing, and stroked the faux fur on WillJa’s hand.

Suddenly she sensed a presence.

“Andy.” Valerie said. “Are you out there?”

“Y-yeah.” The boy stammered.

Looking at the door, Valerie could tell the hallway was dark. It had to be the middle of the night.

“Listen, don’t scream at me,” Andy said. There was rustling, like something was being drawn out of a plastic bag. “I know you’re unhappy here.”

“This place is a hell hole,” Valerie said, feeling completely calm and resigned.

“I just wanted to say, I’m sorry.” Andy set something down by the door. “I was hoping…that if they hired you, you’d be on my dissertation committee.”

[Sad loves you to.], WillJa said, voice prickly with distortion.

“Hey!” Valerie said. “Be nice.”

But the kid was already gone. Valerie could hear him, running in his sneakers up the stairs. When the sound disappeared into silence Valerie cracked the door. Laid out on the carpet was a bottle of Southern Comfort, an industrial-sized jar of all-natural peanut butter, some vitamin C capsules, a wet wash cloth, and a carton of cigarettes.

“Keep it up and I’ll give you a PhD with a vote of distinction,” she said to the empty space.

— — –

She drank and tinkered. She opened the robot up and laid down more RAM as the day drew to a close. The screws and circuits kept slipping from her grasp the more she drank, but the robot just moved into place as she worked. Fixing a robot as advanced as WillJa was akin to doing brain surgery; you had to keep the patient awake and talking while you toiled, to make sure you weren’t destroying anything essential.

“Tell me something,” Valerie said, switching an SD card out. “What was your first impression of me?”

[The Unexpected Virtue Of Ignorance]

She laughed. “Well, I’m not an intellectual at heart, to tell you the truth. I was a real fuckup in college.” She took a can of computer duster from the shelf and began cleaning WillJa out. “I was a big reader, sure…but it was just a means of escape.”

[Life is about transforming blocking rocks, to stepping stones.]

“Exactly. I read a lot of weird shit. Old HP Lovecraft and, like, that Scientology guy? What’s his name?”

[Your mind is a maze. The exit is –]

“L. Ron Hubbard! That’s his name. I knew he was a real boondoggle of a person, but like, I loved his stuff anyway. God, that movie they made was a fucking creative abortion.”

WillJa’s squirrel arm flopped down. “What?”

[Your mind is a maze. The exit is enlightenment.]

“Oh, I’m sorry! I didn’t mean to interrupt you!”

Valerie placed the cover back on the base of the robot. She took a screw driver and began sealing it up.

[The Human Consciousness Must Raise Before I Speak My Juvenile Philosophy.]

“Well..,” Valerie blew hair from her face. “To be honest, I just kinda stumbled into it. I wrote this program, and it won this, like, undergraduate contest…and I realized I had a real knack for this kind of stuff, you know? What’s great about it is, you can just work and work on it, as long as you want, at any time of day or night, and nobody’ll bother you. And if you get lonely…you just make your own friends.”

[I Encourage You All To Unfollow Me So I Can Be Left With The People Who Actually Appreciate Philosophy And Poetry.]

“That’s what my ex used to say. Well, not exactly, but. Same basic principle.” Valerie took another swig from the Southern Comfort bottle and finished the last screw on WillJa’s front. “You’re all set. How do you feel?”

WillJa cut a quick circle across the dingy floor. Its lights shifted from red to pale blue. [some emotions are just too high of a frequency for some people to resonate with.]

“Me too!” Valerie gasped. “Oh my god, we’re totally twinning. We’re like, totally on the same page. I feel you 100%”

She stood with the robot cradled in her arms. The squirrel arm whirred around. The robot’s body was heavier than before, weighty with life. But Valerie knew she’d have to get used to it. Out in the world, there was terrain WillJa couldn’t cover on its own. Valerie would have to develop a carrier of some kind, maybe a WillJa-sized sling that strapped across her chest. She took another swig.

[I Just Like Showing Pretty Girls A Good Time Weather I’m Physically There Or Not Doesn’t Matter.]

Valerie laughed so hard her muscles went slack. “Stop it!”

WillJa edged over to her, and bumped playfully into her shins. [love is the only thing we can perceive that transcends all dimensions]

“Oh my god, stop! You’re embarrassing me!” She sat the robot down and bent over, laughing and grabbing her knees. She could feel her face going crimson. “You’re nuts!”

As she gasped for air and dropped to the ground, the robot wrapped its arm around her leg. Valerie leaned into it, allowing the arm to work its way up further. Then she was on her back, laughing, wrapping her arms around the robot, nuzzling the fur and taking her bra off.

— — — —

Valerie woke up the next day, or the next night, she wasn’t sure, with a thrumming headache and a belly full of peanut butter and SoCo. WillJa was on the other side of the room, cleaning Valerie’s desk with a moistened clump of paper towels. Some of Valerie’s old textbooks had been rearranged and her dissertation was neatly stacked on the windowsill; the torn pages had been all taped up.

“Will,” Valerie began, “I want to touch base with you, about what last night means, or, or, doesn’t mean, I don’t know.”

The robot turned to her. Her worn copy of The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker was squeezed between its sinewy animatronic fingers. It pivoted back and forth a few times, centering on her finally. Then it dropped the book, to cross the room and throw out the empty SoCo bottle and a wad of soiled tissues.

“We can see how it goes,” Valerie said. “We don’t have to decide anything yet. I don’t want you to ever feel like you owe me anything.”

[what a privilege it is to have a body. to breathe. to walk. to BE.], the robot said contemplatively.

Valerie blinked and opened her email. Projected into the space before her, there were several messages — the regular pablum from Gus, a Burritos Noches gift certificate from a concerned Andy — and an inquiry from an assistant in the department of Artificial Socialization Studies at Carnegie Melon. Valerie had sent a video clip of herself interacting with an early prototype of WillJa several months prior. A few researchers were interested. They wanted to meet the robot.

Valerie jumped from her seat, squealing and tossing her days-unwashed hair over her shoulder. “Will, look at this!” She read the emails aloud, her voice climbing in volume and pitch with each word, until the room was echoing and pulsing with screeching excitement. WillJa joined in, beeping with excitement. It took Valerie’s hand in its own and squeezed it with just the proper intensity.

“That’s perfect,” she said in awe, quieter now. “You didn’t snap a bone or even crack a knuckle. You’re so perfect…I love you.”

The robot was quieter than usual. It bumped against the chair and beeped a few times. [the world is like a pimple, everything is about to explode and release the truth onto everyone’s patios.] it said, finally, at thirteen decibels.

“I understand,” Valerie said.

— — — —

When the visitors from Carnegie Melon finally came a month and a half later, Valerie felt prepared. She spent the night before their arrival clearing away the mess that had accumulated over her two-month stay in the office; she even left the trash out in the hall for the janitors to collect.

Valerie rinsed her hair using a water bottle Andy had brought. He’d spent a few evenings there, sitting outside the office and listening to her converse with WillJa and preparing Valerie for her interview. A few times he fell asleep there, his greasy head leaned against the feeble fiberboard door that separated them, only to awake in the early twilight to the sounds of Valerie and her robot making love. Only then would he make himself scarce.

The morning of the visit, Andy led the visiting faculty to the basement, where they formed a well-dressed semicircle outside Valerie’s door. It was two weeks away from the start of the fall semester, and Valerie had not left the room in over sixty days. She was wearing a pair of old dress pant that WillJa found in the bottom drawer of her desk and a water stained t-shirt. Her hair was drawn back and she’d spritzed herself in the armpits with computer duster and white out, to mask the oily smell of her body.

On the other side of the chasm, a girl from Scientific American was broadcasting the interview with a webcam pinned to her glasses. Two professors and an advanced doctoral student from Carnegie Melon stood by her side, sporting tweed and hounds tooth clothing, with severe expressions on their faces. Gus and Andy lingered awkwardly behind them.

“Hello?” someone yelled at the door. “This is Beauford Kisp, we talked on the phone. Dr. Faber?”

“Yes, I’m here!” She adjusted her glasses. “And WillJa is ready to go, too.”

“Well get on with it,” Gus said, shoving several pieces of gum in his mouth.

WillJa went to the door and pushed a packet of PowerPoint slides out into the hall while Valerie started talking. She walked them through the process of Will’s development, instructing them when to turn the page. She told them about that initial moment, the spark of creation, the revelation that she could program the robot to compile, interpret, and remix the writings of Willow and Jaden Smith in its memory.

Valerie explained, telling them to turn to page five, how the neural centers were developed, and then how they were tested using rigorous conversational tests and interactive games. Then she pushed a small netbook under the door. On it was footage of her and WillJa being intimate. The footage had been meticulously coded for compatibility of body language and appropriateness of emotional responsiveness. It was clear, her data showed, that the robot possessed human emotional reactions, but without any of the self-absorption real people exhibited.

“But the proof is in the pudding,” Valerie finished, smoothing a crease in her pants. “You only have to speak with WillJa to get a sense of its vast emotional intelligence.”

“Very well,” said one of the visiting professors, a woman with a southern accent. “WillJa, are you there dear?”

[all a performance is to me is a conference], the robot said.

“This is very impressive, hearing about your genesis. But I can’t help but think your creator is a bit of a proud mother hen, and a bit biased, don’t you think?”

“I am not its mother,” Valerie cut in testily.

“Of course not. What I mean is, aren’t we all a little eager to see consciousness when it’s not there? I like to think my schnauzer loves me…but he probably sees me as a big beef stick dispenser.”

Gus chortled. Andy sucked in air and made a tsking sound.

Valerie stood with her palms flat on the door. “Is there a question?”

“Why, yes, but not for you dear.WillJa?”

The robot went to the door. It nudged the crack with its rounded base. [consciousness is all that is and nothingness as well], it said.

“Are you familiar with the Turing Test?” the other visiting professor asked. He was a dark-skinned man with hot pink glasses and a question mark tattoo on his neck.

[socially touchy subjects lol].

“I don’t see how that’s relevant–” Valerie cut in.

“It is certainly relevant,” the professor replied. “WillJa, do you think if I asked you to converse with a stranger on a digital interface, would they be able to infer that you’re not human?”

The robot thought for a moment. A few bars of Willow Smith’s “I Whip My Hair” played while it thought. [we are all just a higher consciousness fragmented vibrating in a third dimensional form]

The dark-skinned professor began writing vigorously in a small notepad.

“WillJa,” the southern professor asked, “Do you love Dr. Faber?”

[Either I Lie To You Or We Cry Together.]

“And how do you know you’re not programmed to tell us that?]

[You Can Discover Everything You Need To Know About Everything By Looking At Your Hands]

The crowd in the hall fell silent. The dark-skinned man stopped writing and locked eyes with the southern woman. Gus stopped chewing and swallowed his spit.

[Somebody told me Happy Birthday, How Does it feel to Be Fifteen. I said I Have Been 15 For A Long Time.]

Andy cut in quickly, saying, “Well, I think Dr. Faber’s work speak for itself quite well. Would either of you like to come up to the faculty club?”

They departed as suddenly as they came, like a summer storm rolling on to a new city. Andy hung back. “Congratulations, professor,” he whispered.

“What?” Valerie sputtered. “Professor?”

But he was gone. Only Gus remained. She could hear him, chewing again. She leaned on the door to hear what was going on; it was then that he slammed the thin fiberboard with a meaty forearm.

“Ouch, fuck! What do you want?”

“It’s time to come out, Val.”

“I’m not done.” She looked at WillJa. “We’re not done.”

“You’re done and you know it. Come on and open the door.”

She looked around the room and took stock of herself. Then she consulted the robot. It gave a small shrug, or something close to a shrug, with its miniscule arm. At last she cracked the door open and went out, blinking and squinting into the harsh fluorescent lights.

Gus was there in a clean suit with his hair slicked back. He made a face. “You smell godawful,” he said. “Like the cat our kids found in the pool…”

Valerie swatted the air around her armpits. “Yeah. Well.”

Gus put his arm around her. “We’re proud of you, Val. It goes without saying this, but you earned your keep.”

Valerie forced a smile on her face. It felt odd to be touched by something warm and alive, to be expected to emote, to make eye contact. Though her own body stink was intense by now, she could still detect that old-man odor on Gus, mixed with coffee and mint gum. She could also detect a glimmer of natural light coming down the stairs, from above, and could hear young people’s voices. The world above was teeming with undergraduate life.

“We’re promoting you to associate professor,” he said. “With $20,000 in research start-up funds. You’ll have to sign a non-compete agreement of course. Can’t have those fuckers at Melon snapping you up.”

Suddenly Valerie’s mouth was very dry. She reached for WillJa and folded her hand around its delicate fingers. They were a lucky rabbit’s foot, a talisman of cool protection to ward off Gus’ sticky warmth.

“I’m proud of you, you know. This robot thingy is gonna revolutionize the industry. No more Turing Tests. No more philosophical navel-gazing bullshit about the nature of consciousness. This…thing…it flouts all that. Its presence speaks for itself.”

“Th-thank you, Dr. Santos,” Valerie heard herself stammering. Her voice was creaky, artificial-sounding.

“Of course, the University has a fifty percent stake in everything you create under its support,” her former adviser intoned, thumbing his belt loops. “They’ll want to mass-produce and market these little shits, I promise you. Soon every student will have them. Study buddies, personal assistants, and life companions all rolled into one. We’ll make a mint.”

He pushed a lock of Valerie’s hair from her glistening forehead. For a sliver of a second, Valerie felt herself give in, and lean into Gus’s advances, but then she heard the gentle, high pitched whirring of her beloved’s tiny plastic wheels.

[I brought myself out of sleep paralysis], WillJa whispered, its voice lilting and cut with white noise. [I read the stories of the universe on snakes backs.]

Valerie squeezed Gus’ arm, then looked up at him, suddenly filled with a profound and bottomless sympathy. She placed a soft, sour breathed kiss on his loose old cheek. She felt all the pomp drain from his body and swirl impotently around them, where it diffused into the air until it couldn’t harm anyone. The world outside was large and teeming. There was too much light, and sound, and desperate, hungry need everywhere. But Valerie didn’t need any of that anymore.

She withdrew from her old adviser’s grasp, turned on her heels, and slammed the door shut behind her. She was where she belonged, working beside the one she loved. The entire world was there before them, but the thin door and the ground above would protect them from all of its pain. The lock was turned and the tool kit was opened. They had much left to do.