Sympathy for the Narcissist

Can we stop maligning people with a highly stigmatized mental illness?

Humans 101

Can we stop maligning people with a highly stigmatized mental illness?

I’ve been fighting with people about narcissism since the day Trump declared his candidacy. So many left-leaning people seem to relish mental illness as an explanation for his actions. Calling Trump a narcissist seems to satisfy a deep need many people have to understand him as an aberration, an evil defect taking advantage of a system that otherwise works and is fair: If he’s a narcissist, then he’s almost inhuman. Absolutely evil. And all we have to do is get rid of evil people like him, and then we can return to normal.

Of course, the “normal” way of doing things was never any good. Normal American life created Donald Trump. The normal American outlook preaches that there are people who are good and people who are bad, and we can discriminate against the bad ones with a clean conscience. Trump and his allies believe things like that. Our threadbare social welfare system is predicated on that belief. It’s a very reactionary, conservative perspective, yet many liberal people embrace it when the subject becomes “evil” people, narcissists, and Donald Trump.

You can’t actually diagnose a public figure with a mental illness from afar. There’s a reason the American Psychological Association banned psychologists from doing so back in the days of Barry Goldwater. For all the stories we hear about Trump hurling coffee pots at walls and harassing teenage girls, we can draw conclusions about the kind of person he is. But we can’t really know why he is that way. And when we throw explosive terms like “narcissist” in his direction, a lot of blameless people with mental illness get caught in the blast zone.

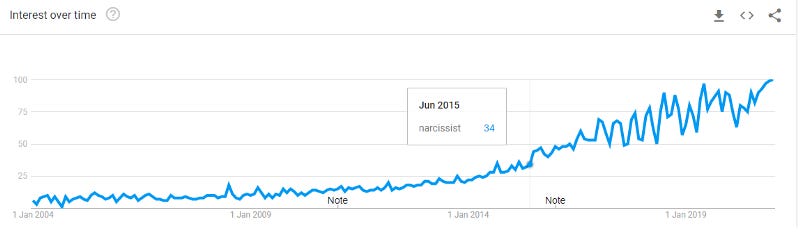

The anti-narcissist industrial complex blossomed during Trump’s presidency. Discourse about the evils of “narcissists” has made its way into countless op-eds, self-help books, and mental health infographics on social media. A growing number of left-leaning people became interested in the pop psychology concept of “narcissistic abuse,” which is conceptually distinguished from regular abuse only in the sense that the victim has branded their abuser a narcissist.

In the anti-narcissist industrial complex, people fall into one of two camps: dangerous, alluring, abusive narcissists, and fawning, sensitive, victimized empaths.

Empaths are encouraged to trust their intuition and push all narcissistic people out of their lives. They’re provided with a laundry list of narcissistic red flags, all of them vague and none of them rooted in peer-reviewed research. Beware anyone who seems charming or whose kindness seems calculated, these resources warn. Don’t trust someone if their emotions seem superficial or they talk about themselves too much.

Never mind that a wide variety of people with mental illness and disabilities such as autism exhibit these traits. Don’t consider for a moment that your instincts might be colored by trauma or bias. You are the aggrieved party, the victim, and narcissists will always be drawn to you. You must always keep your shield raised.

I used to be the kind of person who found these resources appealing. I was escaping an abusive relationship back in 2011, and it brought me great comfort to think of my abuser as a narcissist. The term offered a way of mentally closing the door on him. I needed a reason to stop giving him second chances, and the language of narcissism gave me one. He was irredeemable—basically evil.

Yet, as time went on, I found that seeing my ex as a narcissist and myself as an empathic victim was far too simplistic. The narcissist-empath framework obscured the cruel things I’d said and done, the ways I manipulated and emotionally exploded at other people I loved.

Narcissists are rarely directly observed by science yet are frequently described — and usually in heightened, scandalized language.

My ex was a selfish person with a limited capacity for empathy, it’s true. But upon discovering I was autistic, I realized I shared some of those exact same traits. I also have trouble understanding how other people feel. I also need to be reminded to step out of my own head and consider how I affect others. I don’t think I’m a hopeless case. And as much as I loathe my ex, I wouldn’t want the people around him to think he’s a hopeless case either.

There are contextual factors that explain why my “narcissistic” ex became the violent, cruel person he is today. His own parents and grandparents abused him. When he showed early signs of violence, he was shamed, not helped. His whiteness, maleness, and wealth kept him isolated from other people, and he never developed relational skills. If I want there to be less abuse of power in the world, I need to fight the social forces that created him. The same is true of people like Donald Trump.

What even is a narcissist? Psychologists really don’t know. For all the provocative writing that exists about the alluring evil of narcissists, very few narcissists have been studied closely in the ways depressed people or autistic people like me have been studied. Therapists are trained to never expect a narcissistic patient to walk through their door: Narcissists don’t want help, they’re told. And they can’t really be cured.

Sometimes, forensic psychologists describe incarcerated individuals as narcissistic. Pop psychology writers brand successful yet cutthroat CEOs and elusive scammers as narcissistic quite frequently. Books for abuse survivors often describe emotionally immature parents or cruel partners as narcissistic. But almost all of this is driven by anecdote, hearsay, and speculation.

There is no strongly supported, evidence-based treatment for narcissism. Like most “personality disorders,” narcissism is partially defined by how untreatable therapists view it to be. There is something wrong with the personalities of these folks, after all. That’s pretty close to saying someone is fundamentally broken. In short, narcissists are rarely directly observed by science yet are frequently described—and usually in heightened, scandalized language. Which all seems to me like an only slightly more scientific way of saying they’re monsters.

What defines narcissism? Well, a core part of the condition is having a deep disparity between the self-esteem one projects to the world (explicit self-esteem), and the self-esteem one feels inside (implicit self-esteem). Narcissistic types claim to have grandiose self-images. They seek a lot of outward recognition that they are smart and talented and good. But they also dislike themselves a great deal. Any small slight or setback can wound them intensely. They’re at a heightened risk of suicide, and their suicide attempts tend to have especially high mortality rates.

In other words, narcissists are insecure, emotionally sensitive people who want a lot of attention and struggle to connect and who often hate themselves so much they want to die. How that struggle came to be so widely panned and demonized, I’ll never understand.

Where do these traits come from? Often, abuse—usually childhood abuse and neglect. In fact, nearly every personality disorder is strongly linked to having an intense abuse history. One common criticism of personality disorders as a concept is that they may be, in essence, a label given to traumatized people whose trauma responses are less sympathetic-looking than garden-variety post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

People with PTSD are hyper-vigilant, easily startled, and often very inhibited or self-protective. People with personality disorders try to elicit emotional reactions out of people. They do big, attention-grabbing things to elicit some recognition. They might lie, misrepresent themselves, self-harm, or be unpredictably hot and cold with their loved ones.

These are messier, less likable mental health symptoms. Ones that in media are associated with women and with queer-coded villains. And it’s true, sometimes these traits turn abusive, but other times, traits are just exhausting to deal with. Perhaps that’s part of why many therapists refuse to treat them. It’s easier to live with writing off an entire class of marginalized people if you convince yourself they are “broken” and “evil” first.

I know a narcissist who adopted half a dozen kids. He’s a compassionate, giving person who has let the needs of his children reshape his entire life. He left his old career so his family could relocate to a remote, wooded area that wouldn’t exacerbate his youngest daughter’s asthma. He offers support and advice to new foster parents and adoptive parents on a blog he runs anonymously.

This man is invested in seeing himself as a good person and asks for a lot of reassurance from his kids and others. He can be a bit of a martyr about it. For the past two years, he’s been working on this in therapy because he knows his need for recognition could really harm his kids. His own mother was self-involved to the point of cruelty, and he doesn’t want to continue down that path. He’s a narcissist, and he’s a good man.

Abuse is a misapplication of power. A betrayal of one person’s obligation to others.

I know another narcissist who manages a social justice organization. She trains volunteers, puts together fundraisers, and plans the organization’s initiatives for the year. Like all nonprofits, it’s all a bit dysfunctional, too many hours being worked for too little pay, but she revels in the work because it keeps her mind occupied.

This woman starts almost every sentence with the word “I.” When other people talk about their personal lives, her eyes glaze over. Yet she’s passionate about her organization and the clients they serve. In another era, she might have been diagnosed as autistic or ADHD, but she was an emotionally distant, self-centered woman growing up in the 1960s, so psychiatry says she’s a narcissist.

I sometimes wonder if I am a narcissist, with my endless self-referential writing and the arrogance to post it online, all while suffering from deep-seated self-loathing. I can’t look at someone and feel what they’re feeling. I use achievements to earn love. If someone is sad or anxious near me, it often irritates me. I go to great lengths to hide how selfish I am from other people because if they could see the real me, they’d abandon me forever. In other words, I’m manipulative, grandiose, unemphatic, and lacking in self-esteem.

Hard to tell if this is narcissism or if it’s a natural consequence of being mentally ill in a world that hates weakness and difference. It’s hard to pin down what separates me from the other two diagnosed narcissists that I just described. The more I examine it, the harder it is for me to believe that anyone is truly a “narcissist” in the evil, craven way pop psychologists mean.

Are the monsters we’ve been taught to fear real? Or are there just people who have been mistreated who are using imperfect coping mechanisms and being called toxic for it?

It is troubling to me how many otherwise justice-loving, left-leaning folks want to believe there is a category of people born to be evil. I don’t see how the belief that there is an evil group of people in the world is reconcilable with leftism’s goal of making sure all humans are well cared for.

As a psychologist, an abuse survivor, and an autistic person, I simply do not believe there is such a thing as having a disordered personality. I think there is only behavior and a context for why that behavior happens. That doesn’t excuse abuse. It just helps us make sense of it, so we can prevent it in the future.

Abuse is a misapplication of power. A betrayal of one person’s obligation to others. That’s true whether the abuser has a mental illness or not. I believe the time has come to abandon the concept of “narcissism” and every other tidy, convenient explanation that puts individuals on the hook for systemic issues. It’s our entire approach to mental health, wealth distribution, and human dignity that’s disordered—not the individual people who have been victimized by it. And it’s that broader social illness that we’re gonna have to treat if we want things to change.

…

My book Laziness Does Not Exist is out now. It’s available in hardcover, ebook, and audiobook copies anywhere books are sold.