The Contradictions of Being Tolerated

When your employer celebrates Pride, but bans transition-related healthcare on religious grounds

When your employer celebrates Pride, but bans transition-related healthcare on religious grounds

For over ten years I have taught at the Jesuit university from which I also received my Master’s degree and my PhD. I’ve been a student here, a postdoctoral researcher here, a part-time adjunct instructor, and now I’m a full-time professor. My relationship to the school runs deep. So too do my ambivalences, particularly in a month like Pride month, when it’s most clear to me that my existence as a transgender faculty member is contradictory and fraught.

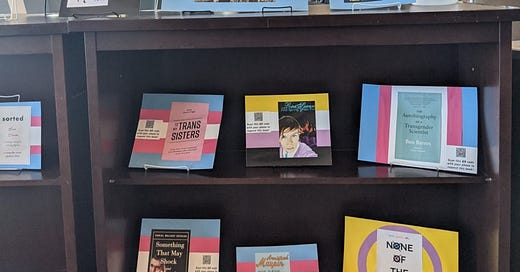

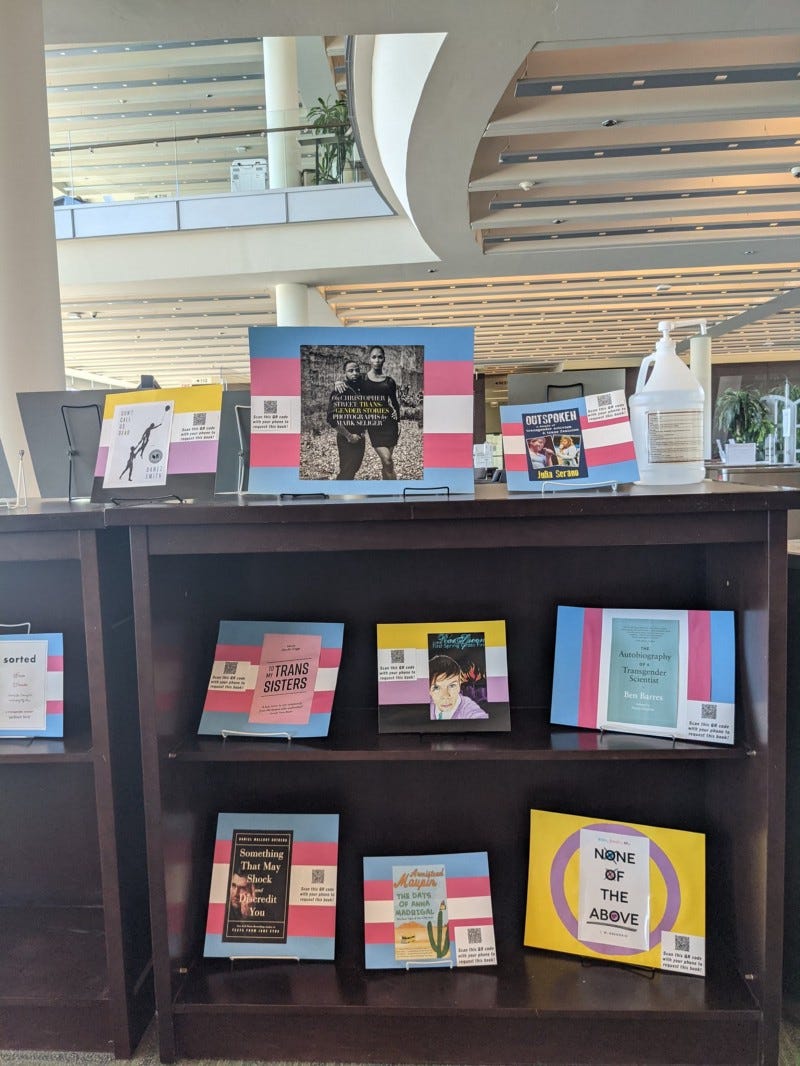

Today I entered the university’s information commons (a computer lab and studying area connected to the library) to find this display celebrating transgender, nonbinary, and intersex authors:

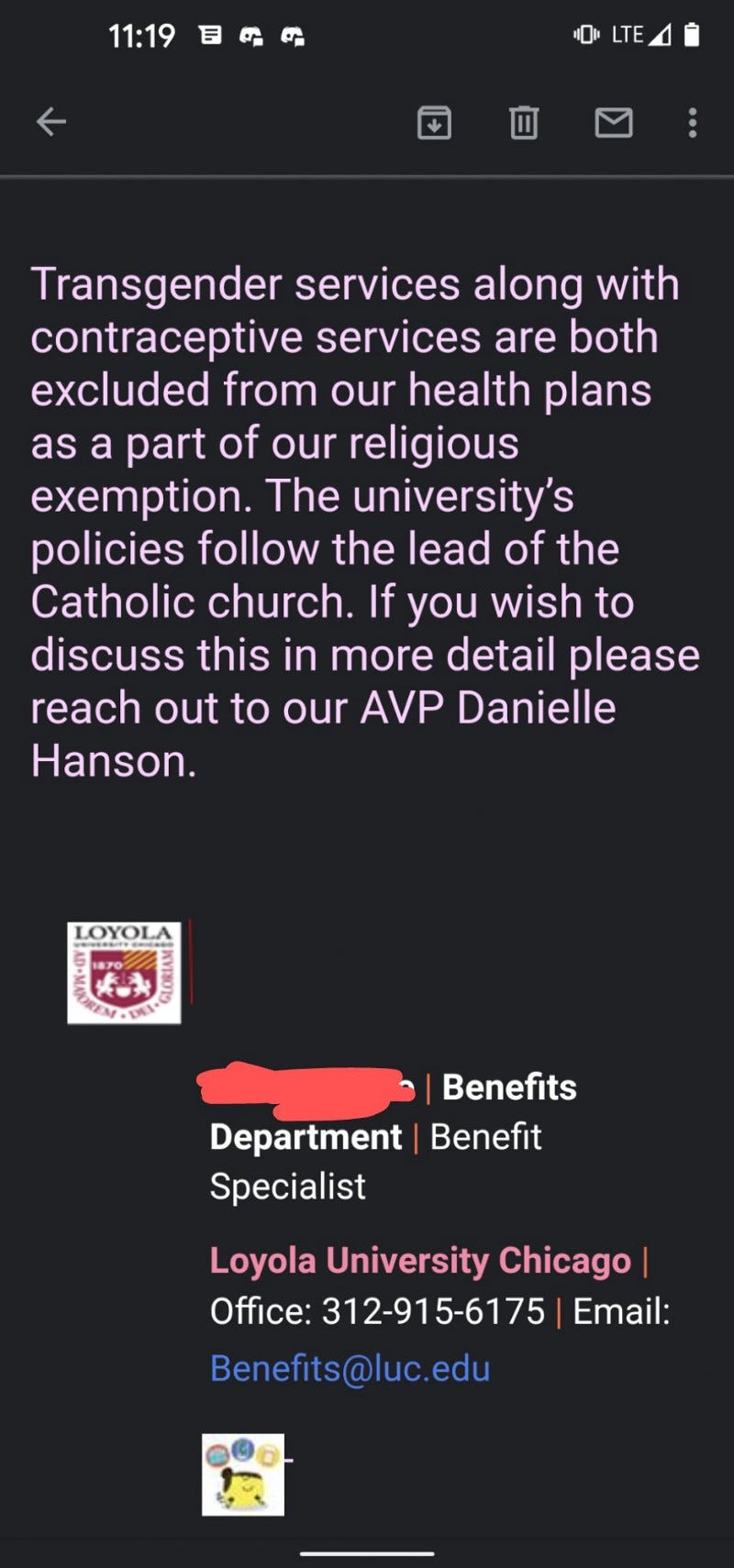

I wish I could feel buffeted and supported by these displays, but all they do is fill me with bitterness. It makes me think of the email I received from the employee benefits department several years ago, when I inquired about whether the university’s health insurance covered transition-related care. I was told the university follows the lead of the Catholic Church, and therefore chooses not to support any transition-related surgeries, hormones, or doctor’s visits, just as it refuses to pay for birth control.

Seeing this cheery pride display also reminds of the time a few years ago, when I witnessed a faculty member accept a prestigious teaching award by thanking the university for allowing him to have a transgender person speak to his class. He spoke with something I can only describe as self-awe as he discussed how fortunate he was to get to challenge his students and open their minds by exposing them to people who were so different.

The idea that a professor at my institution could win a teaching award (at least in part) for presenting a trans person to their class as some novel curiosity chilled me. It clearly had never occurred to this professor that there might be a transgender faculty member sitting in the room as he said all this. He considered himself a bastion of progressive thinking, and clearly the university did as well, yet he couldn’t imagine a person like me belonging among him, holding the same status as he did. To him transness was bordering on the illicit, a shocking thing for a Jesuit institution to permit the acknowledgement of.

While my university bills itself as a tolerant place, it all too often feels to me like its tolerance is simply convenient for its branding. Blue and pink flags and feel-good teaching awards can offer a pleasant scrim to hide the often discriminatory policies lurking beneath. Throughout my time here, I’ve witnessed the school invoke its status as a religious institution in order to discriminate against transgender employees, deny birth control to those that need it, and even use it to block employees from unionizing. I’ve also seen the school position itself as open to all students of all faiths and identities at the exact same time.

I’ve taught at religiously affiliated colleges that were far “worse,” more openly hostile to trans and queer students, too. An Evangelical Christian College at which I once taught stopped scheduling me for classes the moment I began presenting as masculine. Editors have refused to run writing with an accurate bio for me, saying that my pronouns are too confusing or ungrammatical for readers to handle. Hiring managers have looked me up and down and declared my authentic self to be unprofessional. I spent years hiding who I was from the world because I was certain I’d never make my own way in the world if people know what I was.

Because of these experiences, I’ve often found myself feeling thankful I work at a university where I can at least be endured, if not treated equally. But having to live in that liminal space between tolerated and discriminated, between being a persona non grata and a symbol of diversity to paste on marketing materials, is its own kind of harrowing. I never truly know where I stand, never know what the line is between trying to survive, however imperfectly, and being complicit in systems that dehumanize and exploit me. It’s hard to feel pride when you’re just thankful to be alive. I want to be able to expect more, to demand more.

When I was first applying to the university back in 2008, the general application had a worrying field: I was asked to report what my religion was. There was some boilerplate writing surrounding the question, ensuring me that the university welcomed all people of all faiths despite its affiliation with the Catholic Church. I noticed that both “Atheist” and “Agnostic” were options in the drop-down menu. I selected “Atheist,” hit submit application, and held my breath. If they didn’t want someone like me, they wouldn’t take me, I thought. I have since learned that exclusion is rarely so simple.

Later, after I had been accepted into the program, I spoke with a professor about my concerns. She reassured me that though the school takes its Jesuit identity and Catholic affiliation very seriously, the department I was in had many non-religious people. I got the impression that though the institution was religious, we could operate as an island in our own little department, our work and lives not affected by the views of the Catholic Church.

I got my first hint this was not true when I tried to get a birth control prescription from the wellness center some time later. The first nurse practitioner I saw flat-out refused to re-up my existing Orthro Tri-Cyclen prescription. I went home and opened up my health insurance coverage booklet and read that my university refused to cover contraceptive services, citing the religious exemption to the Affordable Care Act’s birth control coverage mandate. However, I read that if I was able to get a prescription written by someone, my birth control pills would be covered by the health insurance company itself.

I dug around online and found a student had posted (anonymously) that there was only one nurse practitioner at the school who would write a prescription for birth control. You just had to tell her you needed the pills for “cramps” or “acne.” You couldn’t mention being sexually active or wanting to prevent getting pregnant. As long as the NP could claim to be treating a medical issue and not providing contraceptive services, she was in the clear.

I booked an appointment with that specific provider. I told her I had painful cramps, and I got my birth control. I tried not to think about how unfair it was that treating my basic healthcare required extensive research and subterfuge and knowing the right person to ask. I wanted to believe I could eke out an existence at the school as long as I knew the right tricks and feints. I was 23 years old and still in the closet about being trans and bisexual, so I knew all about hiding as a self-preservation skill.

Still, I wondered how many sexually active undergraduates came to the university not knowing the school refused to provide birth control. I thought about how many freshman, younger and more vulnerable than me, likely became pregnant in their first year because they couldn’t get contraception on campus. I pondered how many of them might have wandered, distressed, over to the “crisis pregnancy clinic” sitting just one block from campus, instead of visiting the Planned Parenthood a few more blocks to the south. How many young people were pushed into having babies they didn’t want? How many lives were forever changed because they didn’t know the right tricks and feints? I tried not to think about it. I got back to my work.

It wasn’t long before I had to consider my school’s religious affiliation again. After finishing my PhD and postdoctoral assistantship, I became an adjunct instructor. I taught courses for two different departments on campus. Though both departments had many classes to fill, I was required to restrict my teaching load to just two courses per semester, so the university wouldn’t have to give me health insurance.

Since I could not make a living wage under this arrangement, I was forced to stitch together a living by working four different adjunct teaching jobs and some consulting work. I travelled all across the city of Chicago visiting various campuses, teaching from eight in the morning until nine at night. My voice was permanently hoarse. I spent my weekends chugging throat coat tea and lying down, depressed. I couldn’t contemplate coming out as trans. My life was too financially precarious. I had no insurance and didn’t think I could afford gender-affirming care or new legal documents. I focused only on staying afloat.

During this time, the university’s adjunct and non tenure-track faculty moved to unionize. The university invoked its status as a religious institution to resist the unionization efforts. Religious bodies are not under the purview of the National Labor Relations Board, you see. It was a years-long, arduous legal process, with multiple hearings and challenges. Ultimately the National Labor Relations Board determined that while the university was affiliated with the Catholic Church, its employees were not acting in a religious capacity. A part-time instructor of statistics is not a nun or a priest or even a theology instructor, after all. The work we do doesn’t have faith involved. Thus, the school’s claim it was exempted from the NLRB was rendered invalid. An adjunct and non-tenure-track union was formed.

It dismayed me that the university, despite its public positioning as social-justice-oriented, would fight so vociferously to keep from having to pay its part-time workers well. One of the core values of a Jesuit education, according to the institution, is cura personalis, care for the whole person. Invoking religious identity as a reason to prevent looking after employees as whole people (who, being whole people, need living wages and healthcare in order to survive) was a disgraceful contradiction, in my mind. It felt terrible to be treated as an easily exploitable, disposable resource by an organization that prided itself in its investments in the local community.

One year after the adjunct union was unsuccessfully challenged on religious exemption grounds, the university attempted to block a graduate student union from forming. The university claimed that graduate students (despite being assigned regular work hours and being paid & taxed as employees with W-2’s) were not workers, but students.

Graduate students rallied on campus in support of the union and in protest of the school’s resistance. Several were arrested. All they’d done was stand on the very campus where they were paid about $18,000 per year to teach and conduct research, and asked to be treated with the same dignity as other employees. For this, state violence was dispatched against them, and they were silenced.

It broke my heart to see. I remember how hard I had toiled as a graduate student, how little in the name of worker protections I’d had. I knew in my heart of hearts that a compassionate Jesuit institution should want to support their hard-working research & teaching assistants, to help them thrive. I attended protests and spoke in favor of the union when and where I could, but I don’t think it made any difference.

In recent years, I’ve taken on a full-time faculty position, and in my department (the School of Continuing and Professional Studies) I’ve found the accepting oasis I’d always hoped the university could offer. With health care and an annual contract under my belt, I finally felt safe enough to come out publicly at work as trans. My department embraced me and treated me with nothing but warmth. I’ve thrived in my current position, feeling truly supported and respected. I teach working adults, which I’ve always found immensely rewarding.

Outside of my department, though, the university has continued along as it always has, making visible gestures of caring for all people of all identities, but on paper they’ve frequently failed to live up to it. I keep seeing more gender-neutral bathrooms popping up on campus, always in buildings that are student-facing rather than staff-facing.

It doesn’t escape me why that might be. When you’re marketing to prospective students, it pays off to position yourself as progressive. A gender-neutral bathroom in the student union is a branding investment, the social justice equivalent of buying your school a rock climbing wall. It signals that you are cutting edge and forward thinking. But if you only put gender inclusive bathrooms in buildings frequented by students, but not buildings frequented by staff, the implication is clear: you see gender diversity as a young person’s thing, a frivolity to allow in the kids who pay tuition. It’s not a source of diversity, present in all people of all ages, that you fully respect. Plus having a bathroom with a tolerant sign isn’t provocative enough to offend the Catholic Church.

I’ve mentioned these grievances publicly before, and to the university’s credit I’ve never been punished or silenced for it. A few years ago, I collaborated with a faculty member in the Provost’s office to prepare and deliver a workshop on gender diversity in the workplace, and during that workshop I drew attention to the school’s lack of healthcare coverage for transgender employees, and pointed out that it’s a problem we put effort only into accommodating trans students, but not trans staff. I wrote about my employer’s lack of healthcare coverage for transgender people in my book. I’ve contacted the benefits department about my concerns and posted online about how unjust this policy is.

I’m so thankful and relieved I’ve never been retaliated against for saying these things. So far, the only reaction I ever get, when I raise these issues, is a few sad nods from those who know how fraught and complex it is to be queer in a space that doesn’t hate you, but doesn’t love you either. Nobody is surprised, everybody seems a bit jaded about it, and no one feels they have the power to change a thing. I know so many LGBTQ folks, working in so many fields, who are stuck in the exact same kind of spot.

I’m so sick of being thankful for crumbs. Of being terrified to say that I’m starving. As a queer person who came of age in the early 2000’s, I remember how it felt to only ever see queer characters on screen that got sexually assaulted and murdered by the end of the story. Brokeback Mountain and Boys Don’t Cry were the best representation I could ask for. I was actually grateful for the privilege of witnessing such depressing stories on screen.

I was thankful, at that point in the early 2000’s, that gay marriage was a subject of debate. It felt like progress that my rights were an interesting thought experiment to other people, because during my childhood in the 1990s it was simply beyond the pale. When Target first started carrying pronoun buttons, I was so elated I didn’t roll my eyes at it being performative rainbow capitalism. I was so used to being either reviled or invisible that tentative, superficial tolerance was rejuvenating to me.

So for the decade I’ve been at this institution, I’ve been a strange mix of relieved I’m allowed to be here, and outraged at myself for considering mere allowance to be enough. The fight for LGBTQ liberation has come a long way in the course of my adult life, but not all steps forward are equal. Gay marriage is legal. Changing one’s sex and legal name has never been easier where I live. And on a practical, everyday level, having gender neutral bathrooms on campus does make my life easier. Even if I do have to walk out of my office and into a student-serving building in order to use one. It’s insulting to be an afterthought, but I’m used to not be a thought at all.

I am self-protective survivor by nature, and I know how deeply I am inclined to negotiate around conditional tolerance. But I hate how accustomed I’ve become to apologetically, sneakily making it by in the sidelines. I want to be in a space where my full transgender personhood is cared for. I’m tired of accepting what I can get. Months like these remind me I want a life I can take actual pride in.