The "Magic" of Meeting in Person

Inaccessibility, COVID exposure, and productivity loss - that is what's "special" about mandatory in-person events.

To the organizers of [Institution Redacted] Inclusivity in STEM Symposium,

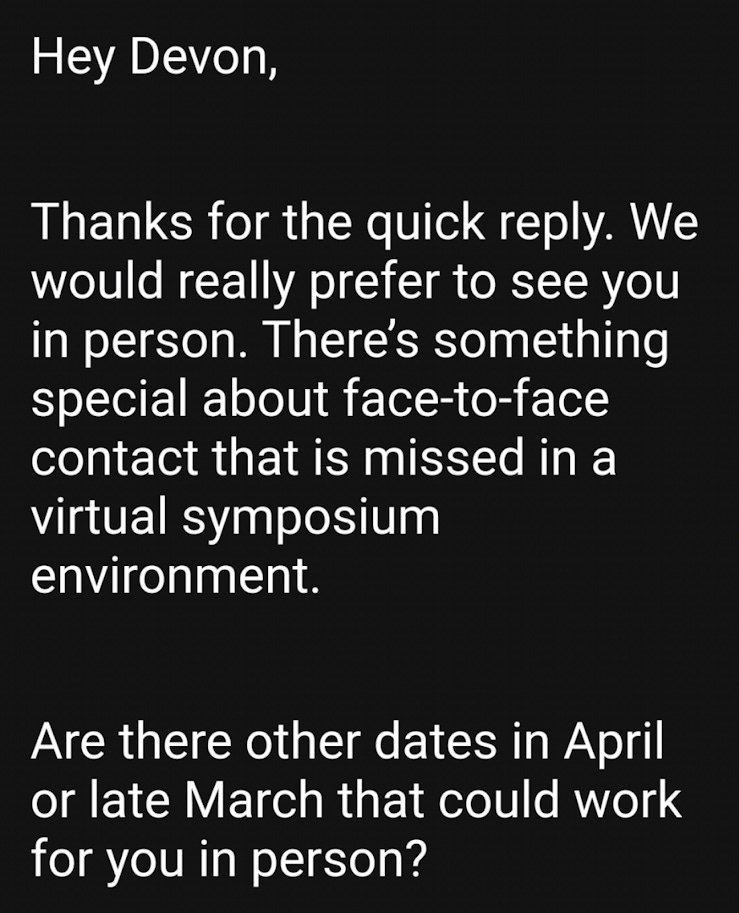

Thank you for your interest in having me speak about neurodiversity at your organization’s event! However, in the spirit of neurodiversity acceptance, I really must challenge your claim that you cannot adapt my talk to a virtual format because “there’s something special” about meeting in person.

I know that for many people there truly is a feeling of a closer, more authentic connection at a live, in-person meeting, and that for them, face-to-face events foster a greater ability to speak off the cuff. Many non-Autistic, non-disabled people feel that a video chat introduces the boundaries of time and distance to the interaction, which can make communication feel halting or artificial. But it is those very same boundaries of time and distance that help to keep disabled people like myself authentically engaged, participating at our own speeds, and protected from the sensory pains and viral risks that an in-person event introduces.

I understand that on Zoom (or the equivalent), it can be difficult to guess at a person’s emotions because you can’t see all their nonverbal signals. Only one person can speak at a time, and the flow of a conversation may be broken up with long pauses or oddly-timed interjections that feel “awkward.” There’s little room for spontaneity — and that’s exactly what many disabled people like about it.

Please know that while an in-person conversation may feel free-flowing, improvisational, and comfortable to you, for many of us Autistics it often registers instead as frenetically fast-paced and high-pressured. The social dance that feels easy and natural to you requires an ongoing, carefully crafted performance for me, and without the protective mediators of a screen, a keyboard, and a modest time delay, it is really quite difficult for me to participate in earnest at all.

You see, for Autistic people, as well as many other attendees with disabilities, the “magic” of meeting in person isn’t really so magical at all. The stressors of an unfamiliar physical environment and the social-performative demands of an in-person meeting makes such events far less accessible to us. The risk of COVID exposure places harsh limitations on which of us are even able to safely attend, and it fills those of us who do show up with anxiety and distraction. Finally, we know empirically that mandatory in-person engagements are far less efficient for everyone — the commutes and flights that must be taken, the hotels that must be booked, the lunches that must be scheduled, the routines that are disrupted, and the “professional” attire that must be bought for such events all waste immense resources and tax us incredibly.

Your institution has created this symposium because it was concerned that disabled people generally do not find belonging or success in STEM, despite the fact that tech work ought to be more broadly accessible than most. You’re also concerned by the data showing that STEM pervasively excludes marginalized groups of all sorts — women, people of color, Indigenous and diasporic peoples, queer people, and those in poverty, and you say you want to take steps to address it. But by denying disabled people a remote attendance option, and even preventing a disabled speaker like me from particpating remotely, you are actually introducing some of the very challenges that exclude members of marginalized groups.

As an Autistic person, I have to mask my disability when I am in public. According to the punishing standards of neuroconformity, my natural mannerisms are unusual, even “freakish” seeming. When I am around other people, I am not allowed to scamper across the floor with my back bent and a scowl screwed upon my face, speaking to myself in odd voices to help keep my attention on track, the way I do when I am alone at home. I may be considered dangerous or incompetent if I do.

In the past, I have been reprimanded by academic advisors for the way I move and sit. When I have made the mistake of feeling at ease and movin g and emoting in the ways that feel best for me, I have drawn stares and concerned questions about whether or not I was “okay.” If I were a Black Autistic, I would almost certainly have been threatened with arrest or police violence at least once for the way my body naturally moves. Instead, people just keep their distance.

Prejudice against traits like these help explain why 85% of Autistics worldwide are unemployed. The typical workplace is not welcoming to people who sway in their seats, chew their hair, run about on their tip-toes, and let out chirps and sing-song recitations of quotes from movies that they love at random intervals. These behaviors might pose a distraction to some observers, including people with disabilities like Sensory Processing Disorder or ADHD. But it’s blessedly easy to mute them on a platform like Zoom.

In order to avoid frightening people, annoying people, or being fired, I have learned to contain my natural movements at in-person events. Many Autistic maskers do. My every step and gesture is strictly regulated. I am hyper-aware of my posture, and I move tentatively, so as not to startle anyone. I don’t speak often, out of fear of using the wrong tone of voice or volume. Rather than providing me the opportunity for authentic connection, being in person makes me feel more exposed and monitored, and so I withdraw. I can’t really hear half of what is being said to me during these moments, because I’m busy with tracking my own behavior.

The rigid social standards that punish me for moving strangely also punish the Tourette’s Syndrome sufferer for their tics, or the person on anti-depressants that make their legs flinch. More than that, unforgiving social rules about how a person must speak and move leads to the discrimination against Black and brown people who are unfairly seen as speaking too “loudly,” and women for showing emotion and seeming “hysterical.” The “magic” of meeting in person, for all too many of us, is being caught within a Panopticon that judges our every word and move.

When I do participate in conversation at a face-to-face event, my primary focus is on not seeming either useless or insane. In-person discussions move too rapidly for me to keep up with in a meaningful way, and they are awash in facial expressions and nonverbal nuances that I can feel being radiated at me, but the meaning of which I cannot grasp. But at an online meeting, I can always focus on the agenda that’s put in front of me, and if I get too overwhelmed to emote, I can just type in the chat box.

In person, I do not have the time to reflect on my true feelings, translate those feelings into words, and locate the right moment to share them in polite, neuroconformist speech. Instead, it feels like I’m steering a runaway train while constantly laying down some new track for myself. You can’t let a comment hang in the air for more than a second without responding to it, or else someone will interrupt you. But you also can’t interrupt anyone else after they have cut in.

And so I reach for whatever superficial word or gesture that will keep the conversation moving, regardless of whether I believe in it. I reach for pre-scripted questions about the weather, repeat cliched jokes and platitudes, and smile in a forced way that gives me a headache, but puts non-Autistics at ease.

They don’t think I’m a cold-blooded serial killer, I say to myself when I retreat to the bathroom to let my face fall. I got away with it this time. I conjured up a specter of an appropriate human and I allowed him to completely overtake me. What’s “special” to me about this interaction is that I’m not there for it at all.

It’s not just Autistic people who struggle with mandatory in-person engagements. Participants for whom English is not a first language may find it difficult to keep up with the pace of a conversation, too. People are who typically interrupted and spoken over (such as Black people and women) may not be able to get a word in edgewise.

By priotizing whomever speaks first and allowing them to hold the floor, most in-person events systematically exclude those who have been conditioned to be least confident, or the most ignored. Deaf and hard of hearing people can’t lipread everything that’s being said at in-person meetings, and so, without the benefit of virtual captions, they too maybe unable to participate. Giving each person room to listen and to be heard is a “special” challenge of the in-person meeting, and great lengths must be taken for it to be assured.

There are also the sensory and physical accessibility issues that an in-person meetings introduce. When a meeting happens online, I can easily attend it from the comfort of my desk, unbothered in my loose boxers and tank top. At an in-person event, I am beating back the sensory pain of a tight belt and rigid shoes the whole time, overheating in my long pants and dreaming of getting home to undress so that I can hear my own thoughts again. Such an uncomfortable presentation environment doesn’t bring out the best performance from me.

I am far from alone in all this. Many disabled people cannot attend in-person events because of the expectation they wear “professional” attire. A study in the journal Society found that strict dress code requirements were a significant barrier to disabled people participating in the workforce.

Many wheelchair users, for example, struggle to find suits that fit them well. People with chronic fatigue conditions may not be able to groom themselves elaborately enough to meet abritrary standards of professionalism. Fat people are harshly policed for how they dress at work — it’s hard to accomplish excellent science as a fat scholar when you’re constantly told that the contours of your own body are inappropriate, no matter what you drape yourself in. It’s also far more expensive and difficult for these populations to find suitable work clothes, too. Sometimes contributing from home is the only viable escape from so much evaluation pressure.

A person with sensory sensitivities like me is just as distracted by the squeaking of chairs and tables and the hum of overhead lights of the conference hall as they are by the restrictive clothing. Disabled people with allergies may be unable to share a space with attendees who wear cologne or use scented shampoos. The long drive to the event may be cost- or time- prohibitive for the parents of children, or those with elder care responsibilities, leading to their exclusion from fields where in-person meetings are mandatory.

When disabled people are afforded the option of attending events online, we can make changes to our surroundings to regulate our own allergies, sensitivities, temperatures and schedules. But in person, we have no such control over how our bodies feel. The unpredictability of our environment is yet another of the threats that makes in-person meeting so “special.”

I would be remiss if I did not mention how many people cannot attend in-person events because of the risk of COVID. On the whole, disabled people face an elevated risk of complications and death when they contract the COVID-19 virus. So do Black people, fat people, and Indigenous people, all of whom die of COVID at elevated rates. Whenever we require that an event occur only in person, we force members of these marginalized groups to weigh their safety against their professional or academic success.

At this point, the rate of prior COVID exposure is so high and the chance of worsened symptoms with each successive infection is so great that nearly everyone in attendance at an event runs the potential risk of developing Long COVID. In a very real way, by mandating that an event only occur in person you are not only reducing the number of disabled scholars that can attend it, but you are potentially creating new disabled scholars who will no longer be able to work as easily in the future.

This is not an abstraction. This is a pervasive way in which society’s most vulnerable members get prevented from participating in STEM industries.

A close friend of mine who works in biomedicine was fired recently, in large part because she insisted on working from home as frequently as possible in order to forestall the spread of COVID. She is neurodivergent, and her job duties were the kind she could complete in solitude at home quite easily. But her employer chastized her, saying that “world had moved on” from caring about COVID, and then let her go.

Another Autistic person that I know, a designer, was fired from her job for continuing to show up to work in a protective N95 mask. Her boss said the mask made her a bad “cultural fit” for a company that so valued social intimacy and the “magic” of face-to-face interaction. “The mask makes it hard for people to relate to you,” this woman’s manager said. “And it makes them feel guilty about coming to visit our office.”

Both of these disabled women cared about the health of others deeply enough to risk ostracization. They watched the rising traces of COVID in wastewater and knew that it merited a response. Yet the abundance of care they showed to others was mistaken for coldness, their decision to socially distance and mask for the sake of safety twisted into a threat to genuine connection. When we mistakenly assert that there’s something “special” about being together in-person that no other method of communication can replace, this is where it leads us. The contributions that disabled people have to offer from behind our protective barriers get completely discounted as not valuable, not worthy of consideration, as not “real.”

Historically, many scientists collaborated using the early precursor to the internet, Usenet, and before that, by exchanging letters. It has always been possible for scholars to work together while apart, and for the more introverted or Autistic among us, that has often been preferable. Numerous STEM professionals of all neurotypes prefer to perform their work duties from the solitude of the home. It seems to only be managers and mid-level administrators who find it difficult to cope in the world of remote work.

This brings me to the final way in which an in-person meeting is “special”: It is especially resource-intensive, time-wasting, and inefficient. To Autistic people like me, who’d much rather skip the circular chit-chat at the water cooler and roll up our sleeves to accomplish our tasks as quickly as possible, the reasons for this are already quite obvious. But even if you truly relish the true emotional charge of being around others, the data unequivocably shows that being in person comes at a great cost.

When lockdown began in 2020, worker productivity increased massively across a variety of sectors. This is in spite of the immense trauma that everyone in the world was undergoing at that time.

Without having to worry so much about commuting, getting the kids to daycare, navigating complex office politics, and attending meetings, workers were able to set their own schedules and focus on the job tasks that mattered the most. With such independence, their output soared by about 41% on average. Employees also became more satisfied with their jobs, because they had more free time for their loved ones and to look after their health.

Though the scientific evidence on worker productivity did not support a forced return to the office, countless managers pushed for it the moment vaccines became widely adopted. They believed, as the organizers of this symposium do, that there is some ineffable “special” quality to being together in person. The widely unpopular return to work caused employee morale to drop, inspired waves of mass resignation, and led business leaders to publish countless works of back-to-office propaganda in the popular press.

Productivity Will Go Down This Year

But you probably won’t hear business leaders talking about it.index.medium.com

In the fall of 2021, I predicted that the forced move back to the office would cause worker productivity to fall. Two and a half years later, I can smugly and yet grimly report I was right. Fortune Magazine reports that worker productivity took a hit at the exact same moment that many employees were forcibly returned to in-person work.

Bureau of Economic Analysis and Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that in the first two quarters of 2022, worker productivity tanked by the greatest amount ever observed — and that is also when office occupancy in the United States rose by 50.4%:

More recent data shows 2022 and 2023 exhibited the most dramatic productivity declines in the entire seventy-five years on record. Much of this can be attributed to the end of remote work.

As more and more business executives are openly admitting, working from home does not negatively impact the quality or quantity of work that employees complete. Leadership at most companies were satisfied with worker productivity in 2020 and 2021, before they had the option to drag workers kicking and screaming back through their doors. And companies that have remained friendly to remote work have enjoyed a whopping 21% boost in adjusted revenue growth, whereas companies that require in-office time have stagnated, according to a survey of 554 organizations conducted by Scoop Technologies.

There are many reasons why the average in-person worker is less productive than the average remote one. The first reason is simple resentment: many workers would prefer to hold onto their autonomy and privacy, regardless of their disability status or identity, and the needless demand that they “show face” at work saps their investment in doing their job well.

The second big reason for the decline is the expense and time expenditure of face-to-face work. Commuting costs $863 per month on average per employee, and takes between sixty and ninety minutes on average every day. Workers who commute pay more for childcare, food delivery, and other services, and have poorer health.

Research by OWL Labs shows that 58% of in-person employees show up merely to keep up appearances at work, only to duck out at the earliest opportunity. This isn’t surprising, given a survey by Slack finding that a majority of workers prefer to complete their more focus-intensive job tasks at home, rather than in the louder, more distracting, less convenient workplace. It is harder to collect one’s thoughts in a public environment — regardless of whether you have Autism, ADHD, a traumatic brain injury, or a relatively more neuro-conforming mind.

Preferring remote communication and work methods, then, is not solely the purview of the Autistic. It’s the preference of the majority of workers. And if digital collaboration methods work so well for the average employee, they can certainly work for the average tech-work-related symposium, too. If anything, a panel session or workshop is easier to translate to a digital format than most collaborative work tasks are.

I have been teaching online for the past 13 years, and I can attest to the utility, flexibility, and accessibility of online meeting methods. My students attend my classes from all across the world. They complete assignments and hack away at shared projects in the late hours of the night, or while waiting on their laundy. They chat with one another in online forums whil riding the bus, and post snippets of code to the class Slack channel when they get stuck. Unburdened by the stressors of a face-to-face confrontation, they open up their hearts and share deeply personal information when it’s germane to the course.

Students with depression and ADHD have told me they feel more comfortable expressing themselves online, because they don’t have to worry about tidying themselves up before heading to the classroom, and they don’t have to filter how they express themselves. A Blind student once told me that in a virtual classroom, he feels less of an emotional distance from his peers. They can’t tell that he’s disabled unless he chooses to disclose his status, and so they treat him like everyone else. A Black female with a strong southern accent similarly shared with me that her peers take her words more seriously online.

As a trans person, I like that online teaching allows me to choose whether to disclosure my queerness or my disability to my students. Because my gender and my Autism are not the first things they see about me, I can be judged on my merits as an instructor first, and not regarded as a political symbol merely for existing. My students don’t have to worry so much about any biases I could theoretically apply to their appearance, identity, or mannerisms, too.

Before I knew that I was Autistic, I found opening up to other people completely impossible to do in person. My entire face-to-face persona was an elaborate performance designed to avoid marking me as the “other.” But I was able to be more honest online. In blog posts and emails to trusted virtual friends I could unspool the tangled contents of my mind, and reach out in quiet desperation for support. It was online that I first fostered any sense of community, and came to recognize myself as a marginalized person living in a state of societal exclusion.

There is something truly special about meeting online. At its best, the internet can broach the borders that separate us, and allow our most self-protective walls to recede. Digital accommodations help us to parse messages we might otherwise find confusing, and give us the words that we might find too difficult to speak. The screen is at once both a bridge and a container for our psyches. And those of us with unruly minds and noncompliant bodies desperately need both.

I do enjoy being around others physically, but only when I know that I am safe from judgement, when I am free to dress myself and move my body however I want, and when I am joined together with other people in shared celebration without high stakes. For me and for many disabled people, these are conditions that a professional or academic setting can never meet, because we are too disposable within them.

Work environments are veiled in constant threat — the threat of firing, the threat of arrest, the threat of being cast aside for being too angry, too difficult, and too weird. There, we need some distance. We need control over which sides of ourselves that we reveal. We need a mask — both figuratively, and in order to prevent people from getting sick.

I hope that if your organization truly cares about improving inclusivity within your field, you will reconsider your mandate that this symposium only happen in person. What happens face-to-face is alluring to many, but it can also be maddeningly superficial and biased. If we wish to forge academic and professional environments that welcome Autistic people, ADHDers, Blind people, Deaf people, immigrants, women, people of color, wheelchair users, plus-sized people, long COVID sufferers, parents, and anyone else with accessibility needs, we have to recognize the empowering, equalizing “magic” of meeting virtually, too.

I thought you might be interested in the DDS guiding values which are read at the beginning of each of our multiple-times-a-week peer support sessions:

Peer support guiding values

~We value all ways of showing up and sharing: camera on, camera off, verbally, in the chat. There is no need to share at all, just by being present we’re all part of the space and supporting each other.

~If you would like your message in the chat to be read aloud, simply add that to your share. If you want to speak but the conversation is moving very fast or you’re having trouble jumping in, raise your hand and the host will invite you to speak.

~ We value silence. If there is a natural pause after someone shares, it means that people are processing, thinking, gathering their thoughts for their own share, or typing in the chat. It never means that you said something wrong or awkward. People may also jump in immediately. That’s all part of the natural ebb and flow of the conversation.

~ There is no being late or leaving early. Feel free to come and go whenever, no need to explain or apologize, or to check out before leaving.

~ There is a weekly topic that serves as a starting point for shares. From there we spiral out and the conversation evolves naturally. Tangents and sidetracks are welcome and encouraged.

~ We are peers; we leave the professional ‘hats’ we might wear at the door. We do not speak from a place of authority and we do not give advice.

This made me weep. Everything I’ve been trying to say, everything I’ve felt for four years clear and validated here. Will be sharing this for a long time to come. Deepest gratitude.