“Thoughts are Not Feelings” is Shitty Psychological Advice

It’s time to stop spreading unscientific, unhelpful mind-body dualism.

Originally published to Medium on June 22, 2022. Why I am moving my archive to Substack.

If you have been in therapy before, or have ever picked up a cognitive behavioral or dialectical behavioral therapy book, you have likely encountered the adage that “thoughts are not feelings.”

This observation is often intended to help a therapy client distinguish between their interpretation of a situation (and what their thoughts are telling them about that situation) and the emotional reality of how that situation affected them. Take for example this passage from the Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Workbook for Bipolar Disorder by Sheri Van Dijk:

One difficulty that people often encounter when they begin to examine their emotions is determining the difference between an emotion and a thought.

For example, when I ask a person how she felt in a situation, she may respond by saying, “I felt that I was being criticized” or “I felt that he should have understood how I was feeling.”

If you look closely, you’ll see that she didn’t actually describe an emotion, but instead stated what she was thinking about the situation.

Van Dijk does on to explain that this patient is actually feeling angry or disappointed by how she was treated. But as Van Dijk acknowledges in her own text, determining the difference between a thought and a feeling is really quite difficult. Our emotions shape how we perceive the world, what we think about, how we evaluate information, and how easily we can “break away” from repeating an upsetting idea to ourselves over and over again.

Conversely, the content of our thoughts impacts our emotions. When we dwell on unhappy subjects, we make ourselves physiologically and psychologically more sad. When we are used to interpreting others’ behavior in the most negative possible light, we move through life routinely feeling belittled, judged, and alone. The relationship between affect and cognition is a two-way street that is never shut down. So why do we even bother trying to cleave thinking from feeling in the first place? They don’t operate separately. They bleed into one another, shift and intertwine and progress in parallel, always.

“Thoughts are not feelings” is also something that patients who heavily intellectualize and analyze their emotions tend to hear from their therapists — especially when a therapist thinks all that analysis is blocking the patient from sitting with how they truly feel. Take for example this exchange I had with a therapist many years ago:

Me: Yet another friend of mine is struggling with suicide ideation and depression.

Therapist: And how do you feel about that?

Me: It feels like there is nothing I can do to protect people or to help people get better. It’s like everyone around me is reaching out for an emotional life preserver and I’m the only one in the boat. But I can’t take everyone in, and if I try to, I’ll end up drowning too.

Therapist: That’s a thought, not a feeling.

If my therapist’s goal was to help me connect with and validate my own emotions, she could not have done a worse job. Rather than hearing the anguish and panic evident in the metaphor I provided, my therapist decided to correct me for expressing my emotions in a way she didn’t approve of. This made me trust her a whole lot less, and it made me feel that the way I emote is somehow “wrong” in her view, and that I shouldn’t open up to her judgmental, censoring ass anymore. (Though I’m sure she’d want me to just say her actions made me feel mad or ashamed).

When therapists chide their patients to share a feeling, and not a thought, they are typically requesting the patient provide a straightforward affect word such as “joyful”, “irate,” “disappointed,” “bashful,” or “sad.” And if I pondered it for a moment, I could explain in this case that seeing so many friends suffering did in fact make me feel both guilty (because I could not help them all sufficiently) and sad (because witnessing their pain brought me sorrow).

However, in that therapeutic appointment, I did not feel that emotion words such as “sad” or “guilty” did justice to the enormity of what I was going through. My mood was not just a tiny bit struck by my friends’ crises. I was alarmed and had been alarmed for weeks, and quite literally could not stop thinking about it. My mind kept generating panicked thoughts about how much was on my plate, and how little I could to do to make a difference in the lives of others. Emotions were embedded into the content of my thoughts. My thinking was clearly quite subjective, flowery, and intuitive — it was emotional. Yet my therapist shut me down for conveying my feelings by sharing my thoughts.

Unfortunately, this approach is very common under a variety of therapeutic approaches. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) teaches patients to avoid so-called cognitive distortions by identifying whether their thoughts line up with reality. If a patient’s thinking is not strictly rational or grounded in evidence, then they are encouraged to dismiss or set out to “disprove” those thoughts. In this therapeutic approach, any and all emotions are considered valid, and to some degree unavoidable — but inaccurate thoughts are treated as a problem a person must train themselves out of having so often.

Since our feelings and thoughts are impossible to fully untangle, it’s hard to put this approach into practice fully. How can I really allow myself to experience my sadness without also observing that my mind is flashing with images of my family members dying? How can I find space to acknowledge my anger, when that anger primarily takes the form of internal rants about how misinformed everyone is and how nobody ever listens to me? Those thoughts also reflect my emotional reality. If my therapist were to neglect them because they aren’t “really emotions,” they’d overlook a huge part of my interior experience.

Dialectical behavioral therapy (or DBT) also involves instructing clients to draw a firm line between their thoughts and their emotions. Returning again to the Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Workbook for Bipolar Disorder, Van Dijk tells the reader that a statement such as “I’m an idiot!” is a thought, not a feeling. But is there a more emotionally charged thought to have than one that rejects your entire selfhood like that? It’s hard to imagine ever thinking of oneself as an ‘idiot’ and not experiencing a flood of negative emotions at the same time.

To say merely that one is feeling ashamed and embarrassed is to lose specificity in this case. “I’m an idiot!” (or “I feel like an idiot”) conveys that a person is experiencing profound negative emotions directed toward themselves, and that those negative emotions are connected to concerns about intelligence and capability, probably provoked by a perceived-screw up. That says a lot about why the client is upset and what past experiences and future concerns are being activated by their present situation. Why would a therapist ever want to replace such a rich, contextual discussion with vague faffing about their feelings?

Another reason that therapists and self-help books distinguish between thoughts and feelings is because many people do try and use their intellects to push unpleasant yet unavoidable emotions away.

Take for example my old colleague Brendon, whose parents had expected him to serve as their translator and unpaid employee when he was very young. Helping to manage a small business’ legal documents and keep its operations afloat at the age of ten years old had been incredibly stressful to Brendon. He had stomachaches and anxiety migraines as an adult that dated back to the experience. Yet whenever Brendon discussed his past, he was quick to dismiss his own trauma by highlighting all the generous things his family had done.

“My childhood was not perfect,” he’d say to me, after describing a harrowing encounter with government officials that he was forced to navigate on his parents’ behalf as a child. “But my family paid for my college, and they love me, and they moved to this country when they were in their mid-thirties and the adjustment was so very hard.”

It’s clear in this case that Brendon was engaging his intellect in order to keep feelings like resentment and sorrow at bay. In social psychology we sometimes call this motivated cognition — the practice of using our thoughts to arrive at the conclusion that we want. This is yet another way that thoughts and emotions cannot be cleanly severed from one another. We often try to think our way into feeling certain things — just as we often feel our way into specific thoughts.

Would it have been helpful for a therapist to redirect Brendon away from his motivated cognition with the phrase “thoughts are not feelings?” I don’t think that it would. Because in addition to the intense emotions Brendon was experiencing, he was going through a variety of meta-emotions too. Meta-emotions are the feelings we have about our own feelings, particularly feelings we’ve been socially conditioned not to discuss.

For instance, if a boy grew up learning that it was unacceptable for him to cry, he might become angry with himself for experiencing sadness as an adult. His anger is a meta-emotional reaction to his sorrow. I happen to experience this one a lot, by the way. It’s only in the past year that I’ve finally learned that when I feel the desire to go on snarky, cruel social media rants it’s often a signal I’m burying some sadness I think is too ‘pitiful’ to feel. I’m a toxically masculine man who hates his own weakness, and so I start intellectualizing away from my sadness by thinking very deeply (and very emotionally) about all the bad takes on Twitter that piss me off.

Brendon felt bad about resenting his parents. But he did not believe resentment was an emotion he deserved to have. And so he covered up his resentment with the meta-emotion of guilt — and that meta-emotion came with a series of specific, corrective thoughts. His parents did so much for him. His parents struggled so much more than he had. Their needs should always come before his own.

Brendon probably heard these messages from his parents as he was growing up — or he had it reinforced for him by the surrounding culture. There are a lot of conflicting influences and contradictory emotions swirling around inside of Brendon — and if we focused only on his emotions, and not on his thinking, all that complexity and personal history would be missed.

Many Autistic people are highly familiar with the complicated meta- emotional and cognitive maze that Brendon found himself wandering. We tend to live largely in our own heads, detaching from an overwhelming world by dwelling on our ideas and personal interests. We also are quite accustomed to being told that our reactions to things are incorrect.

One interview subject that I spoke to for my book Unmasking Autism, a young woman named Crystal, told me that she would experience meltdowns as a child when an unexpected change of plans threw her for a loop. If her elementary class had field day instead of indoor recess, for instance, she’d thrash and cry on the pavement in distress. Another interviewee, Eric, told me he used to get cranky and snap at people when he was at busy work conferences that became too noisy — particularly when the sound system made crackling feedback sounds that only he seemed able to hear.

None of the neuro-conforming people around Crystal understood she needed a consistent, predictable structure to her day, and no one planning Eric’s professional conferences recognized that Autistic people like him often require safe places to retreat from social data and sound. And so instead, both Crystal and Eric were frequently told by others that they were explosive, being sensitive “babies”, or making their feelings up. Experiences like these teach Autistic people that we cannot trust our own feelings, and that we should always closely analyze our reactions and make all our “wrong” emotions go away.

Because of these numerous invalidating and censoring experiences, most Autistic people are quite bad at knowing how they feel — especially in the heat of the moment. Scientists often call this inability to recognize emotions and body sensations alexythimia, and it manifest in many ways.

Autistic writer and researcher Stevie Lang has observed that during sexual encounters, Autistic folks can’t always tell if they have genuinely consented to an activity, or if they merely want to want something for the sake of pleasing their partner. During an argument with a loved one, an Autistic person’s speech might become clipped and loud without them even realizing that they are angry. An Autistic person I spoke to told me that she needs days to process and reflect on an experience before she can tell how it made her feel.

I am often the same way. Big losses and surprises throw me for a loop and leave me numb. “I’ll think about this and get back to you” is a life-saving phrase in such cases. My partner knows that when we experience any challenge, I’ll probably send them a lengthy text message explaining my true perspective and needs after a day has passed. It’s just the way I work. It’s how I and many Autistic people cope with the fact we reflexively censor and block our feelings. And have been blocked.

Thinking is part of how we arrive at how we feel. So for a therapist to tell us that all this crucial interior work is invalid because “thoughts are not feelings” is devastating. It shuts us down and makes us feel like we are wrong about ourselves all over again. This is only compounded by the many other invalidating experiences Autistics have in a standard therapy office, such as being told that our emotions look too “flat” or that we explain experiences in too much detail. We are always to much or too little. We truly cannot win.

Therapy Isn’t for Everyone

Let’s talk about the people harmed by mainstream mental health

Most therapists are non-Autistic white women who, for a variety of cultural and sociological reasons, believe that empathizing with a patient by looking at their face and instantly identifying how they are feeling is key. But Autistic people don’t work like that. Non-Autistic people are bad at detecting our emotions. Our facial expressions and nonverbals don’t look like theirs. We often convey our inner truth through lengthy stories, elaborate analogies involving our special interests, complex systemic analyses, and media references that echo how we feel inside.

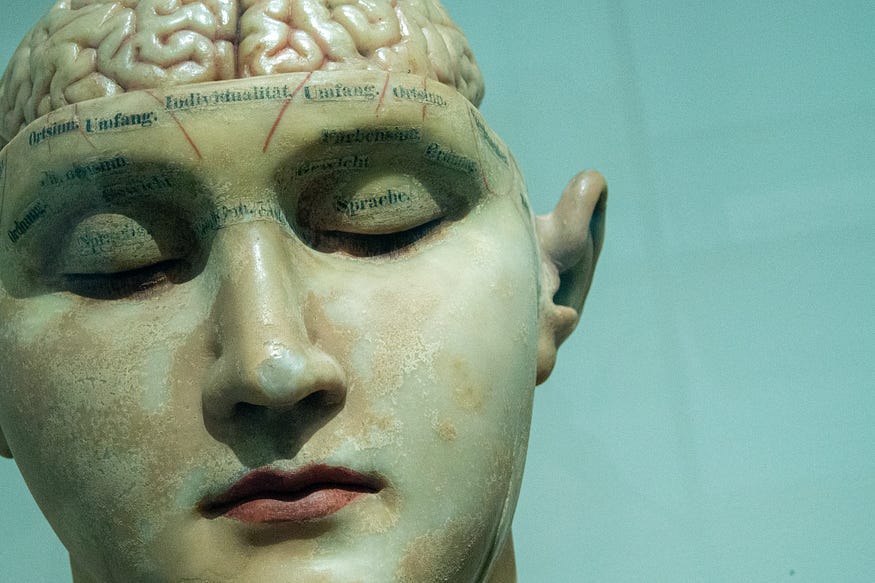

Thoughts are feelings. And feelings are thoughts. Just as behavior is communication. Many decades ago, psychologists and neuroscientists did away with the concept of Cartesian Dualism, which tried to look at the mind and body as separate entities. The philosopher René Descartes believed the body was physical matter, and that it operated on animal instinct — which is still how many people talk about emotions today. He also claimed the mind was entirely spiritual, not physically instantiated, and that it was rational and moral in ways the body could never be. None of this is actually true.

No, Mental Illness Isn’t “Caused” by Chemicals in the Brain

Biology is how our moods and mental states are expressed, but it’s not the root cause of them.

We know today that the mind and the body are one inseparable whole, and that no process inside of us is free from the influence of other interior (or external) forces. Our gut biome affects how we feel. Our beliefs about food can alter our metabolism. Our facial expressions can shift our moods. Despite the numerous metaphors we hear claiming otherwise, our bodies are not objects that we “own,” and our moods are not random wind storms that pass through us without reason or purpose. Everything’s connected. All of it is us.

Our thoughts and feelings are inextricable. And to fully understand the emotional element of human psychology, we must take into account, and validate, all of the rest. I just hope neuro-conforming therapists learn all that soon.