What “The Vow” Can Teach Us About Unhealthy Groups

The NXIVM cult was dominated by toxic positivity, vague hierarchies, and the allure of all-powerful leader. Many workplaces and families…

The NXIVM cult used tactics more commonly seen in abusive workplaces and families.

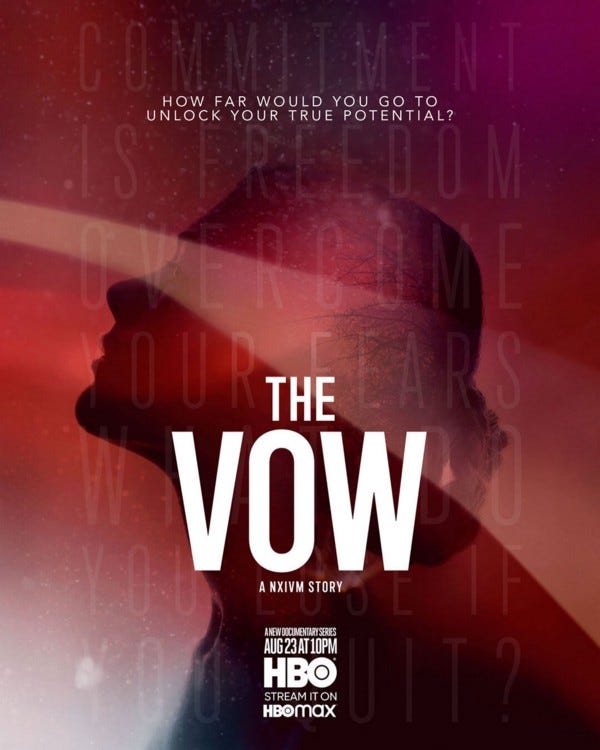

Like a lot of people, I’m currently obsessed with the HBO documentary series The Vow, which chronicles the rise and fall of the multilevel marketing scheme, “personal development” program, and cult of personality known as NXIVM (pronounced nex-ium).

NXIVM operated semi-successfully for over twenty years, making money by offering motivational seminars in their “executive success program” (ESP for short), and carefully drawing a handful of seminar attendees into its more intensive “stripe path.”

NXIVM was alluring enough (and on its face, normal-enough) to attract the interest of mainstream, successful documentary filmmakers, actors, heiresses, and the children of royalty. In the first few episode of The Vow, the organization looks like a fairly benign, if pricey self-help program: lots of weekend-long classes on “exploring meaning”, investigating childhood fears, and setting intentions and goals.

Then, in episode three the viewer gets hit with a whammy: beneath NXIVM’s cheesy, corporate-coaching veneer, there was an intricate, oppressive system of manipulation, ritual enslavement, and sexual exploitation. High-ranking, conventionally attractive women in NXIVM were slowly groomed to join DOS, or Dominus Obsequious Sororium, a self-improvement “sisterhood” where each member was both a slave to someone higher up the chain, and a master to several women she recruited beneath her. At the top of the hierarchy was founder Keith Raniere, who was the “grand master” to all “slaves.”

In DOS, “slaves” had to offer up nude photos and incriminating videos of themselves as signs of devotion. They had to ask their “master” for permission to eat, sleep, or send text messages. DOS members were held down as a cauterizing gun branded their bodies with the initials of the group’s founders. Having sex with Keith Raniere was obligatory for many DOS members. Beyond that, there were additional layers of equally disturbing thought control: NXIVM’s leaders were said to be the reincarnated souls of Hitler and other Nazi officials, members were forced to watch video footage of gruesome murders, and dissenting voices within the organization were ostracized and labeled “Lucifierian.”

How did it all go this far? How did a bland self-help seminar lure people into mental abuse and sex trafficking? As a social psychologist, I’m interested in group dynamics and social norms, and how they can slowly push people to alter their behavior and beliefs. While NXIVM is an extreme case, the organization took advantage of people using the exact same tactics that run-of-the-mill unhealthy groups do.

You see the exact same tactics NXIVM used in many toxic workplaces, abusive families, and codependent relationships. By studying the ways that NXIVM operated, we can learn a lot about how to avoid cultivating unhealthy relationships in our own lives, as well as a few interpersonal “red flags” that might signal to us that a group is controlling and unsafe.

So, what made NXIVUM so appealing, and so effective at manipulation? What is a sign that a group you’re in is controlling you? Let’s take a look:

Toxic Positivity

Part of NXIVM’s immediate appeal was how bright and positive it seemed to be. In old videos of their seminars, members are constantly smiling, hugging, and goofing off with almost childlike glee. Every word uttered by founder Keith Raniere seems to prompt applause and laughter. Members greet one another with kisses on the cheek. Men in NXIVM reported finding the group to be warm and supportive in a way their other male friendships just weren’t. Women described the organization as empowering.

Cults often pull in new members using “love bombing”, a showering of warmth and affection that makes the group seem special and safe. Toxic workplaces like Enron infamously utilized love bombing to cultivate loyalty. Jim Jones, David Koresh, and Charles Manson all used love bombing to lure people into their cults, too. Sometimes love bombing takes the form of being physically embraced or lavished with sexual attention, but more often, it’s about absolutely overwhelming a new member with attention and affection.

Love bombing works because it erodes a person’s defenses and upends their normal social expectations. It makes a lack of reasonable boundaries seem like a sudden, intense connection. Euphoric, love-bombed cult members make commitments to the group sooner than they otherwise would: investing tons of money, logging long hours, abandoning friends and family to live on the group’s property.

Ex-NXIVM member Barbara Bouchey mentions in the documentary that as a child, she received very little physical affection or loving support from her parents. Once she started attending ESP classes, she was bathed in positive attention, which made the group hard to resist. Before long, she had become one of the founder’s many devoted girlfriends — despite not being attracted to him. She felt grateful to Raniere for forming such a loving and supportive group, and her boundaries were stripped away, until she found herself trapped.

Toxic positivity leaves no room for complexity or interpersonal conflict. If you’re never allowed to be sad, listless, or resentful, you can’t bring your full, human self into a group. In NXIVM’s case, this oppressively upbeat culture was reinforced by the belief system their seminars preached: ESP courses claimed that all negative emotions could (and should) be eradicated. This brings me to the next unhealthy group dynamic:

Emotional Invalidation

Members of NXIVM were taught they should be “at cause” of all their emotions. People were responsible for creating their own reactions and feelings, the logic went, so any negative emotion they experienced was their fault. This included even reasonable reactions of fear or alarm. Founder Keith Raniere railed against members having a “victim” mentality, and taught that claims of abuse were, themselves, abusive.

Members of NXIVM were trained in invalidating and erasing their own emotions. They were made to watch videos of beheadings and gruesome sexual assault scenes from movies, and berated for reacting to those videos by crying. Raniere preached that a strong enough mind could even turn physical pain into pleasure. Under this framework, even traumatic moments such as the forced, ritual brandings were cast as transcendent and beautiful.

NXIVM’s workshops appealed to people because they offered an alluring promise: if you learn to take control of your life and your emotions, you never have to be angry or overwhelmed again. You can achieve all your goals, and stop holding yourself back. You never have to be a “victim”. This outlook sounds empowering, until you recognize that it bars anyone who genuinely is victimized from ever speaking out or seeking justice.

This flavor of emotional invalidation is very common in multilevel marketing schemes, toxic workplaces, and emotionally abusive families. For example most MLMs preach that if a member is not meeting their sales and recruitment goals, it is because they lack the optimistic attitude necessary to succeed. If any criticisms are raised about how the company does business, leaders dismiss them as a person “choosing” to have negative attitude and to self-sabotage.

When I was in graduate school, I noticed this logic was trotted out whenever a struggling student was forced to drop out due to personal emergencies or mental illness. The problem wasn’t that our graduate program failed to accommodate students with disabilities, you see. It was the student’s fault for not having what it took to succeed.

My program wasn’t particularly abusive; it was a run of the mill graduate program, overly demanding and insufficiently supportive, and led by faculty who fondly remembered having been browbeaten by their own mentors when they were young. Though it was a far milder form of emotional invalidation than what NXIVM peddled, it still did significant damage. The same is true of many workplaces, activist organizations, and academic programs that blame victims of injustice and exclusion for their own struggles.

Language Control

Another way that NXIVM kept its members isolated and in line was by using alienating, confusing language that no one outside of the group would understand. Thinking about the causes of bad feelings was called having an EM, or an “exploration of meaning”. Feelings of depression or anxiety were “disintegrations.” Giving nude photographs to your master wasn’t extortion or blackmail, it was “providing collateral.” Acronyms and odd turns of phrase were abundant, as were clichés that reinforced the group’s beliefs and norms.

Obscure, group-specific language makes it very easy to communicate with people inside the group, and incredibly difficult to reach anyone outside of it. It also restricts the experiences and perceptions that members are able to name. When “explorations of meaning” replace all conventional forms of “therapy”, there is no room to talk about seeking outside help. When punishment and physical abuse is labeled “penance”, it’s hard to recognize something damaging is going on.

In Robert Lifton’s classic book on the psychology of cults, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism, he describes how jargon and “thought-cancelling clichés” help unhealthy groups control their members and warp their thinking. “The language of non-thought” pacifies people and derails difficult conversations. Thought cancelling clichés can come in the form of trite phrases, such as “it is what it is,” or they can be group-specific and ideologically motivated, such as NXIVM’s branding of every doubt or boundary as a “limiting belief.”

Many corporate environments control employees’ language with clichés, niche acronyms, and jargon that makes no sense to outsiders. You also see it in restrictive faith communities, radical and reactional political groups, and self-help circles that aren’t rooted in genuine psychological science. Benign-seeming, cutesy language can easily be used to alienate people from more trustworthy information. One prominent example that comes to mind is the pop-psych language of “highly sensitive persons,” or HSPs.

HSP is not a clinically observed or validated category; though self-help books on being “highly sensitive” are incredibly popular, they’re rooted on scientifically very shaky ground. Many of the people who self-identify as HSPs would qualify for an Autism, Sensory Processing Disorder, or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder diagnosis. A vague, feel-good term like “highly sensitive person” can be far more appealing than any of those “scarier” mental illness labels. But by identifying with that label, so-called HSPs remain isolated from the neurodiverse community they’re actually a part of.

Qanon is another example of a group that uses niche language to control people and cut them off from community. One of the group’s rallying cries is WWG1WGA, or “where we go one, we go all,” a thought-cancelling cliché that reminds members to put up a unified front and go along with the crowd. The belief in made-up chemicals like adrenochrome cut Qanon followers off from genuine science. You can’t easily test your beliefs against trustworthy research when you believe in things that no scientist has ever published a study about (because it doesn’t exist). Qanon’s terminology also makes its members sound really unhinged to non-followers — which of course keeps them lonely and therefore dependent on the group.

When a group imposes obscure, unfamiliar language on its members, and requires that those words replace more commonly-known terms, it puts a bubble around members’ reality. By replacing mental health language with nonsense terms like “limiting beliefs” and “disintegrations” NXIVM made it much harder for followers to recognize the psychological pain they were in. They were suffering under a powerful structure of control they could not even name.

Vague Yet Powerful Hierarchies

Cults are always vertically organized, even if they claim to be democratic or egalitarian. Typically, a cult will exert power over its members by making hierarchies incredibly difficult to break into, or to understand, while also giving those hierarchies immense power behind the scenes. High-ranking officials may impose firm rules on lower-ranking members, all while using thought-cancelling clichés to claim that no rankings or rules even exist.

This combination of vagueness and power is effective for several reasons. First, it’s very hard to rally against leadership when that leadership denies its own power. Coercion can easily be framed as an individual member’s “choice.” Keith Raniere did this constantly. For example, he claimed that though he was at the head of DOS (and the master of every enslaved woman), he was not responsible for it. Each woman who was coerced into accepting a brand on her body was making a personal choice to submit. Abusive workplaces and religious cults similarly dismiss accusations of coercion by saying members “chose” to be there.

Second, by making its means of advancement vague, cults keep their members feeling insecure and desperate to please. When there are clear benchmarks of success in an organization, it’s easy to see when someone is being treated unfairly. If you know exactly what is expected of you, then you can make a clear decision about what you’re comfortable with, and estimate your odds of success. When a group instead operates through a shadowy system of inconsistent reward and punishment, no one ever feels safe. No matter how much you devote yourself to the group, it is never “enough.”

In NXIVM, this dynamic was used to pressure women into sexually servicing Raniere; in an abusive workplace, it often takes the form of a pervasive, unspoken expectation that employees work long hours without complaint. In activist spaces or nonprofits, it may feel like a cloud of guilt is hanging over everyone. In abusive families or friend groups, it may instead take the form of desperately fighting to please a powerful patriarch or charismatic leader. Which brings me to the next toxic group dynamic:

A Distant Yet Ever-Present Leader

If you’ve watched other documentaries about cults (such as Holy Hell or Wild Wild Country), you may have noticed cult leaders tend to have a few attributes in common. While followers describe them as charismatic or charming, on camera cult leaders often seem kind of passive or flat. Many are soft-spoken and gentle. Much of the harm they do is by proxy, manipulating advisers and followers into acting harshly on their behalf. In both The Vow and Wild Wild Country, some of the worst abuse is initiated by a woman at the cult leader’s side.

Why is this the case? To really understand it, I think we need to look at the research on abusive and emotionally manipulative families. Within an abusive family, there is often a parent (or multiple parents) who is in the main source of terror. However, their abuse may be supported or facilitated by the entire family structure. If one child fights back, the rest of the family may blame them for “provoking” the abuser’s wrath. If anyone speaks publicly about the abuse, they may be ostracized for making the family look bad. Every relationship within the family is warped by the desire to please and placate the abuser, and to erase evidence of their crimes.

In NXIVM, Raniere had an entire fleet of supportive girlfriends who helped enact his abuse. When his ex Barbara Bouchey challenged Raniere or upset him, he didn’t lash out at her directly; instead he fell silent, and his girlfriends swooped in to “correct” Bouchey and harass her until she apologized for upsetting him. High status “masters” in DOS passed down Raniere’s expectation that all “slaves” cut calories and remain waif-thin; Raniere rarely had to dirty his hands by issuing such dictates himself. To earn an audience with Raniere, members had to please high-ranking officials at NXIVM first, most of whom seemed far more authoritative and controlling than he was.

Yet while Raniere remained kind of distant and aloof, his presence was symbolically everywhere. The major “holiday” of NXIM, V-Week, was a celebration of Raniere’s birthday. Photos of Raniere and his co-founder Nancy Salzman were prominently displayed at the front of every seminar room. He appeared only rarely, at private meetings or late-night volleyball games. This dynamic elevated him to the status of almost a god, powerfully influencing all affairs from afar, never facing accountability.

Corporations may erect similar cults of personality around their founders; leaders like Steve Jobs and Elizabeth Holmes carefully constructed images of themselves as cool, calm, mysterious, and all-powerful. Demigod-like leaders shape the beliefs and goals of everyone within their organization. Members may be taught to memorize their quotes, or asked to ponder “what would [the group leader] do?” in all situations. Rank-and-file group members are encouraged to police one another’s behavior, “on behalf” of this distant, all-powerful leader. People’s motives and boundaries are no longer their own; instead, they become symbolic extensions of the leader’s will.

Sunk Costs

The final unhealthy group dynamic that plagued NXIVM was the sunk costs associated with being a member. In order to earn the coveted “green sash” ranking in NXIVM’s stripe path system, members had to render the company upwards of a million dollars in class fees or in “services”. To progress in the group, recruiting new members (or in DOS, new “slaves”) was compulsory. If Raniere took an interest in a woman in NXIVM, she was expected to give up more than just money and social connections: she would be “invited” to give up her old life to live near Keith in Albany.

The more you sacrifice for the sake of a group, the more psychologically and materially challenging it is to leave that group. How can you admit to yourself that twelve years of your life were a complete waste? How can you rebuild a regular life when you’ve given a cult leader your entire life savings, and haven’t worked a “regular” job in years? Will your old friends forgive you for trying to recruit them into your downline? Can your self-esteem take the hit of having to crawl back and apologize?

Famously, the LDS Church helps indoctrinate its members by sending them on years-long mission trips when they are young. Mormon missionaries are assigned to postings far away from all their family and friends; until very recently, they were banned from calling, texting, or video chatting with their families. In addition to being cut off from their loved ones, missionaries are required to proselytize to the public, knocking on doors and harassing random strangers on the street about the status of their souls.

This pushy sales pitch isn’t actually designed to win new members into the LDS fold. The real goal of the mission trips is to teach the young missionaries that the outside world is hostile to them. By sending young, impressionable Mormons on a lonesome, two-years-long trip where they constantly get doors slammed in their faces, the church ensures they feel immense relief upon finally returning home. Their lifelong loyalty to the church is cemented. Whatever chance they had at an outside life was lost.

MLMs use sunk costs to control people in similar ways. If you’ve spent thousands of dollars on Lularoe merchandise, it’s hard to walk away from the company. You’re desperate to keep selling, both to dig yourself out of the financial hole you’ve created, and to psychologically justify everything you’ve lost. Nonprofits dabble in the same logic at times; employees and volunteers are often implicitly expected to suffer for the causes they believe in; that suffering is then used against them, to justify their continued involvement. You wouldn’t want all that sacrifice to be for nothing, would you?

Identifying Unhealthy Groups

So what can we take away from all this? What can The Vow teach us about how abusive groups form and take root? Let’s sum up the common tactics employed by controlling groups:

· “Love bombing” attracts new members, and erodes their boundaries

· Toxic positivity is used to silence all concerns and complaints

· Members are taught to “control” their emotions, and remain happy at all costs

· Victims are blamed for creating their own anger, trauma, or resentment

· Obscure language and jargon shapes group beliefs and limits contact with the outside world

· “Thought-cancelling clichés” pacify people into compliance

· Power is hoarded; the existence of a hierarchy is hidden or denied

· Confusing, unspoken expectations keep members insecure and on-edge

· The existence of coercion and manipulation is denied

· Conformity is framed as an empowering personal choice

· Members are taught to police one another’s behavior and thoughts

· Every individual is responsible for enforcing the leader’s will

·Members are pressured to offer money, time, and social connections to the group

·Past sacrifices and losses are used to justify future ones

·The outside world is viewed as hostile and unsafe

While these tactics were employed by NXIVM in a particularly intense way, you have probably encountered most of them in your everyday life to a lesser extent. Maybe your family explains away the cruelty of a racist uncle with this thought-cancelling cliche: “that’s just the way he is.” Or maybe members of your church use gossip to manipulate people into dressing more conservatively. Perhaps you have a co-worker who tattles on you to the boss, making it easier for the boss to micromanage you.

As The Vow illustrates so well in its opening episodes, victims of cults are not uniquely weak or gullible people. They’re regular human beings. And before they were held down and forcibly branded, NXIVM members assented to dozens of much smaller, more benign-seeming forms of social pressure. The tactics listed above are everywhere, because they are both subtle and effective. And each of us can work to make our own social groups less restrictive and oppressive by refusing to take part in them.

Whenever we blame victims for their misfortune, or tell depressed people to quit whining, we are contributing to toxic positivity. When we enforce group conformity instead of welcoming healthy conflict, we contribute to groupthink. When we use language policing to judge people, we isolate ourselves from the broader social world. Conversely, when we encourage respectful dissent, honor our emotions, walk away from things that make us uncomfortable, and stand firm by our boundaries, we are helping resist conformity pressure and curtail abuse.

Most of us won’t ever end up in actual cults. However, we can all work to encourage diversity of thought within our social circles, to ensure that our own groups become less cult-like in their own right.