When I Was Borderline

If it’s situational, is it still a ‘personality’ disorder?

This piece was originally published to Medium on May 10, 2022. Why I’m moving my archive to Substack.

The news that an expert witness in Johnny Depp’s defamation trial against Amber Heard diagnosed Heard with Borderline Personality Disorder has gotten me thinking a lot about my past. So has the ensuing public discussion about Borderline, and the public reflections some BPDers have written about the immense stigma the diagnosis carries. Conversations about Depp’s addictions and potential self-injury and narcissism have given me real flashbacks to my old life too.

As someone who endured emotional and sexual abuse in past relationships, I see ghosts of myself in both Heard and Depp. I remember how it felt to be blocked from leaving my apartment, and forced to withstand a barrage of verbal attacks and insults, as Depp claims he was by Heard. I also recall how it felt to be permanently on edge around an unstable partner, feigning smiles and constantly scanning him for signs of an explosion, as Heard says she had to do with Depp.

I even know how blurry the line between abuser and victim can become in your mind when you’re in the thick of it. Like Heard, I sometimes escalated fights because I could not stand walking away from an unresolved conflict. And like Depp, I sometimes spat out witheringly cruel bon-mots and then coldly shut down. Like Heard, I took all of my partner’s failings personally and amassed resentments, which leaked out of me in acts of passive aggression. And like Depp, I have struck myself or downed bottles of liquor in front of a partner, trying to show them just how much pain I was in.

I don’t know anything about the real Amber Heard or Johnny Depp. I have no idea whose story is more true, and which allegations are accurate, if any. And unlike either party, I don’t have a substance addiction or personality disorder diagnosis. I’m just Autistic, with a history of being abused, difficulty predicting and regulating my own emotions, and social skills challenges that have made me seem desperate and volatile at times.

When I was younger, my behavior was textbook Borderline. But it’s not now. And that’s because I, like all other humans, am a product of my past experiences, my present environment, and the psychological tools I currently have at my disposal. When my life improved and I learned effective coping skills, I became a more stable, secure person. I wasn’t “cured.” I was still disabled. I had just finally been planted in a place where healthy habits could take root.

My experiences illustrate just how contextual and relational personality disorders can be. Though clinicians are taught that personality disorders are lifelong or even incurable, a person’s degree of dysfunction often waxes and wanes as their environment shifts. So does it really make sense to describe a pattern of insecure and distressed behavior as being caused by a ‘disordered’ personality?

Let’s explore.

…

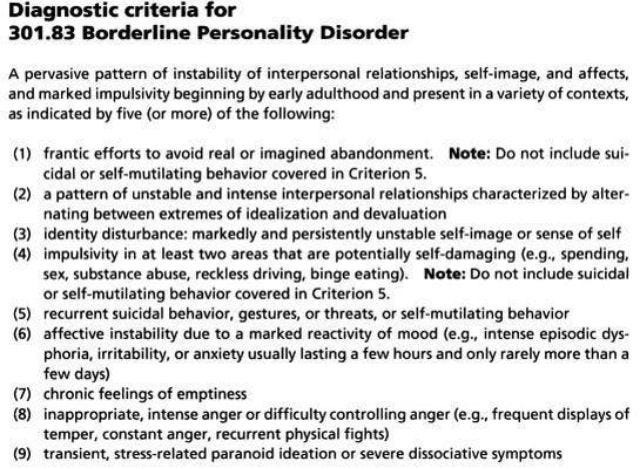

When I was being abused and did not yet know I was Autistic, I exhibited textbook Borderline Personality Disorder traits. I had intense, swerving emotions, and lacked a consistent personal identity. I needed a relationship in order to define who I was, and spiraled into panic whenever that relationship was threatened. I engaged in rapid-fire “switching,” alternating between thinking my partner was my very favorite person and resenting everything about him. I self-harmed and had mood swings. I felt as though sadness and loneliness were external forces that could somehow kill me.

These are traits Amber Heard has been described as having, pretty much to the letter. Some of our similarities are eerie: in one audio recording, Heard begs a withdrawn, drunken Depp to continue an argument with her. She’s breathing heavily and letting out guttural whimpers and sobs as her words keep looping around themselves. She says that by stepping away from the conflict, he is “killing her.”

I was exactly this frantic and animalistic when my abusive partner and I had arguments. I’d provoke and escalate, becoming hysterical and demanding resolution. Like Heard, I’d beg him to stop making me feel like I was going to die. It seemed to me that my partner’s actions determined my emotions entirely, and that without constant signs of his approval, my entire existence might cease. I refused to walk away from a conversation until it either resolved, or he turned violent.

I remember running sobbing from my abuser’s apartment at four AM one evening, while he shrieked threats at me from his door. It had begun as a fight over how poorly I’d cleaned his stove, but then ignited into something far more dangerous. His words carried on the air and followed me as I dashed down the stairs, around the corner, and onto the Jarvis Red Line train platform. His apartment was eye level to the platform, so he kept glaring at me from an opened window and screaming, continually, for ten minutes until my train arrived.

An hour later he texted me, saying he was headed to the West Coast to be with his ex-girlfriend Anna. He often leveraged their relationship to punish me when we were fighting. Though I’d just bolted from his apartment out of fear of being struck, I could not stand the idea of him leaving. I sent a flurry of desperate messages. How dare he do this to me. He needed to forgive me. I demanded he take me along with him on the trip.

While we were in Seattle, I found condoms he’d packed for his dalliance with Anna. I threw all of them out in an impulsive, wounded fit. I knew this would inspire him to have unprotected sex with both me and Anna, but I didn’t care. I wanted to punish us all. It seemed fitting to me that we all might catch a sexually transmitted disease — a external marker of the interior dysfunction we all shared.

I hated my abuser but I didn’t want him to leave me — not even after all the radiators he kicked, the walls he punched, and the times he held me down to prove a point about his strength. I stayed with him for another ten months after that train platform incident. I was both miserable and an absolute torment to be around that entire time.

Was I crazy? Was I Borderline? Was I a controlling, vindictive abuser myself? Or was I just an Autistic person, lacking in social skills or much internal self awareness, clinging to an attachment that satisfied my needs for connection and stimulation when nothing else could?

To me, it’s a distinction almost without a difference.

…

There area variety of circumstances that might lead a person to behave in a manipulative, unpredictable, or even “personality disordered” way. As many as 90% of Borderline sufferers were abused or neglected as children. In most instances, Narcissistic Personality Disorder appears to arise from growing up in an environment with little warmth or genuine acceptance. Some professionals suggest we view both conditions as problems of attachment and relational ability, rather than disorders of personality.

If you have never seen what a stable bond looks like, it makes sense you would try to connect to others by being needy, inauthentic, or entitled. And if you don’t know how to calm yourself when you’re coping with rejection(or the torment of, say, a sensory overload) you might look pretty unstable and scary to others. And if you don’t understand how your own mind works, it makes sense you’d need another person to define your identity for you.

I’ve written before about how Autism and narcissism have dovetailed in my life. Since I can’t read people’s emotions very well, I often have to use my own experiences as evidence of how they might be feeling. This can make me look self-absorbed. And since I was a very socially awkward but intelligent kid, I learned from a young age to hinge my self-worth on my accomplishments. Unfortunately, this can make me seem egotistical or grandiose.

And when I was a lonely, undiagnosed Autistic adult, I allowed myself to get into many unhealthy and insecure relationships. The instability of those relationships made me look very Borderline.

Sympathy for the Narcissist

Can we stop maligning people with a highly stigmatized mental illness?

I’m far from the only neurodivergent person in this position. Numerous masked Autistics (who don’t know they are disabled until later in life) are initially misdiagnosed with personality disorders like Narcissism or Borderline.

In my book Unmasking Autism, I quote a Black Autistic woman, Nylah, who was first diagnosed as Borderline. Nylah used to change her appearance and interests to suit the preferences of her romantic partners. It was the only way she knew to signal to somebody that she liked them, and wanted to become close. Nylah’s mother had many narcissistic traits when Nylah was growing up, and had demanded her daughter serve as a mirror to herself.

Whenever a boyfriend started requesting time alone or tried to break up with Nylah, her entire world shattered around her. She contemplated suicide often, and attempted a few times. Psychiatrists initially saw her as abusive, and manipulative. Misogynoir almost certainly played a role in how negatively she was perceived. Eventually though, both Nylah and her mother got diagnosed as Autistic.

Nylah says that once she learned to study healthy relationship dynamics with the fervor she once used to mimic boyfriends’ personalities, her life dramatically improved.

“Autism can make you quite obsessive,” she says. “I used to fixate on everything about the men I was in love with, so I might grasp what made them tick and how I might suit them. And when I turned that hyperfixated energy onto something more useful to me, like practicing small talk and learning how a conflict-repair cycle ought to look, I actually started getting what I wanted out of my relationships. Which was always a feeling of safety.”

…

Autistic people do glom on quite intensely to our “special interests.” And when our special interest is an actual human person, the fixation can mimic the way Borderline people attach devotedly to a “favorite person,” or FP. As Nylah’s story underscores, Autistics tend to be socially excluded, so rejection hits us very hard, just as it does personality disordered folks. Neither group is wrong for finding abandonment so terrifying. Most of us have experienced profound isolation quite frequently.

It’s difficult to tease apart the difference between being too dependent upon a partner in a “Borderline” way, and being profoundly excluded due to Autism and reliant upon a partner as a result. When I was obsessed with my own abuser, I did very much want other interests and friends. But I had no idea how to get them, and his physical presence was the only thing that emotionally soothed me. So I clung to him. Pathetically. And I manipulated situations so I could maintain the closeness that I craved.

Autistic people are vulnerable to relational abuse, because we tend to be gullible, impoverished, and frankly, kind of socially desperate. That’s yet another thing we have in common with people with personality disorders. Though personality disorder sufferers are demonized for the coping mechanisms they adopt, they really aren’t any different from us. We use the same flawed tools. We suffer from the same kinds of traumas and exclusions. And we both stand to benefit from a world that is more inclusive and accommodating toward difference.

…

As knowledge of myself as an Autistic person grew and I found opportunities to practice my social skills, I became less manipulative and needy. When I escaped the tumultuous, abusive relationship I was in, I became more psychologically stable. In therapy and with the help of a few great self-help books, I learned how to step away from triggering situations and manage difficult emotions.

Today, I am still a passionate person with massive feelings, who loves hard and craves intense experiences. Mentally, I still sometimes “switch” on the people that I love, or get caught in a rumination wormhole I find difficult to escape.

But behaviorally, and relationally? I’m a completely different person now. I can quiet my crying jags and check my worst fears against reality. I use mindfulness, exercise, and sensory regulation to keep myself from exploding in sadness or self-hatred. When I need something from another person, I know how to communicate it directly.

I don’t act Borderline now, or Narcissistic — but I still intimately understand the mentality of people who cope in less effective ways. I recognize the many ways in which my own worst actions were influenced by my history, and the constraints I was operating under. So it pains me when I hear other psychological professionals describe BPDers as hopeless or exhausting, or I witness everyday people equating these diagnoses with being an evil abuser.

Embracing neurodiversity is not just for misunderstood Autistic people like me. It’s for every single person who has ever had the way that they think, feel, and cope treated as innately toxic. Everything is contextual. Abuse isn’t caused by mental illness. Abuse occurs when power is exploited and turned against the vulnerable. Under the wrong circumstances, nearly any of us could be “Borderline,” “Histrionic,” or “Narcissistic.” And with the right foundation and the room to heal lifelong wounds, nearly any ‘personality disordered’ person can find belonging and begin to thrive.

There is an overlap between autistic and BPD traits, such as emotional instability even if the triggers for this instability are different. Where the problem lies for me is that GROUP DBT can be far more confusing and distressing than helpful for autistic individuals with BPD traits.

This is a really interesting article. I was also misdiagnosed with a personality disorder before finding out I was autistic. Its left me with a very strong distrust of psychiatrists. The psychiatrist saw me for all of 30 minutes and told me I had BPD without doing the full diagnostic interview which apparently takes several hours. He then passed me off to his assistant who prescribed me antipsychotic medication that I didn't need. It took two years for me to get a referral to a very understanding psychologist who did the full diagnostic interview and told me I didn't have BPD but some of the answers I'd given in the interview had made her suspect that I was autistic. I'm still dealing with the trauma of the misdiagnosis and the lasting effects of the antipsychotics. I was going to make a formal complaint about the psychiatrist but a friend who works in psychology told me there's no point because the psychiatrist would just say it was his professional opinion and you can't make a complaint against a doctor's opinion. So the arsehoe is still probably misdiagnosing vulnerable autistic people with no consequences. It makes me so angry.