This piece was originally published to Medium in March of 2022. Why I’m migrating my archive to Substack.

I’ve been working on setting better social media boundaries lately. The more my follower count climbed on platforms like Twitter and Instagram, the more comments and direct messages I received —and the smaller the percentage of worthwhile messages became. Though I was accustomed to using social media to make new friends and hold enjoyable conversations about social and economic justice, neurodiversity, and whatever nonsense Grimes was up to next, my notifications had increasingly become a source of torment and stress.

I was getting Jokerfied, and fast. I could feel myself becoming less patient with redundant but entirely-good faith questions. Requests for information about my personal life were making me feel preyed upon and surveilled. And though I’m an absolute advice column addict and just started writing my own, I began downright resenting the numerous, highly intricate dilemmas and traumas complete strangers kept dropping in my inbox.

I wasn’t the only one who noticed that my social media habits were falling out of step with my anti-work, anti-people-pleasing ideals. A friend of mine, also named Devon, let me know that several highly active Instagram “mutuals” who were unfailingly polite to me were downright sexist and predatory to her. My partner observed that I was devoting a lot of energy to processing the emotions of complete strangers — energy my sensitive, easily drained Autistic self doesn’t come by easily. Some commenters criticized me for becoming too short-fused and snarky.

That last one really got under my skin. How dare my followers ask for so much free content, commentary, and support, then turn around and critique the tone in which I delivered it to them? Though each comment and message came from a unique individual with their own constellation of feelings and problems, I experienced my notifications as a coordinated barrage of demands. There were simply too many of them, and too little of me.

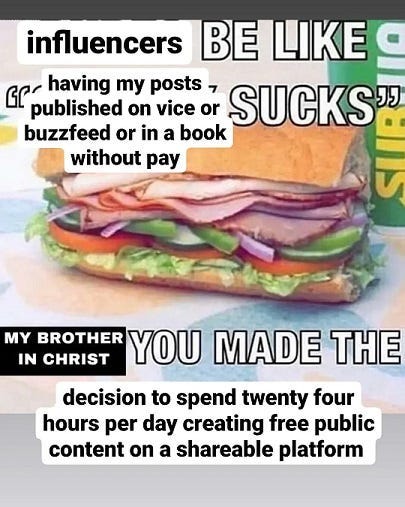

Of course, I was the engineer of all of these problems. I had decided to create social media accounts and post writing to them on a daily basis. It was me who kept my inbox open to strangers, literally inviting the responses of tens of thousands of people. My actions had trained others to expect approachability and responsiveness from me. And if I found that giving that much of my time and attention away was no longer working for me, or enriching my work as a writer, well, I’d have to be the one to change it.

It was time to give myself peace — and the stillness and silence necessary to form my own thoughts. If I wanted to continue being an effective writer and a loving, emotionally present friend, I’d have to heal my relationship to social media.

And so, I turned my comments off. I disabled message requests on Instagram and Twitter, so now the only people who can message me are people I already talk to regularly. I restricted my notifications to only the people I follow — turning my social media apps into, essentially, group messaging platforms for staying in contact with my actual friends. I’ve also started restricting many of my Twitter threads so that only my friends can reply to them.

It has been absolute bliss. I haven’t known such solitude and mental clarity in years. Here are some of the many improvements that locking down my social media has brought into my life:

I’m not constantly checking notifications.

Like many people, I became a compulsive app-refresher during the pandemic. Social media provided me with fortifying social snacks during a time when I was starving. Looking at what people were posting and commenting was one of my sole ways of finding stimulating novelty and contact.

But the electrifying surge of social media notifications stung just as much as it energized: my attention was frayed and frantic, my heart always racing, my eyes forever strained. When my platform grew, notification-checking took on significantly higher stakes: there was always a fresh crop of racists, ableists and transphobic exclusionists leaving hateful messages on my pages, and an even larger crop of (perhaps) benevolently ignorant folks dropping bad takes and misinformation.

Now that no one can comment on anything I post to social media, I can just sit back and let my words stand for themselves. I don’t need to argue with people who have misinterpreted my work, or correct obvious misreads. When my phone lights up, my heart doesn’t lurch into my throat out of fear that somebody’s used my page to broadcast slurs. If I want to stay off social media for several days, I can — there are no comments to moderate, no potential fires to put out.

I’m no longer platforming nonsense, misinformation, or oppressive language.

A comment section is an information distribution platform, albeit a small one. Even if you don’t endorse everything your commenters have to say, you are, by virtue of having a comment section, providing people with a place to share their ideas — and a built-in audience for those ideas. Since I never had the time or patience to thoroughly moderate my comment section, I was providing my followers with a fertile field of bullshit.

I always went through my posts and removed the most deeply objectionable replies, of course, but I couldn’t keep up with every single person making half-baked claims — for example, allies asserting that the word “transsexual” is always problematic (it isn’t) or that some Autistics don’t get diagnosed because they have “female” bodies (that’s not the cause of masked Autism). Then there were the more pernicious, but stealthier comments: people claiming that men are innately more violent than women, for example, as way of arguing for policing and prisons.

I’ve spent years diligently building my social media platforms and public identity as a writer — why would I willingly lend the following I’ve accrued to any random person hanging around in my mentions? It makes absolutely no sense for me to provide that outlet to just anyone. In fact, I have come to believe it’s downright irresponsible for me to do so. Reading through comment sections and DMs is a habit-forming time sink — and I’d rather spare both myself and my readers that distraction.

I have more time (and brain space) for actual writing.

My inbox and comment sections used to be flooded with repetitive questions that individual people (quite understandably) could not recognize as repetitive. What should I do if I think I might be Autistic? Should I transition if I feel x, y, and z? Why don’t you like the term “female socialized”? I want to learn more about abolition, any reading recs?

I used to think I had a responsibility to answer these questions endlessly. I’m an educator! I’m lucky that so many people care what I think! And I do have answers to many of the questions I receive. The thing is, I’ve already shared those answers — here on my Medium, as well as in Twitter threads, Instagram grid and story posts, and highlight reels. And oh yeah, in the two books I’ve written.

One of my favorite things about writing is that once a project is done, it lasts forever. I can conduct my research, lay out my arguments, and then leave the work behind for anyone to discover and ponder when they’re ready. I’m not a patient person. I’m hasty and my mind moves way too fast. With my writing, I can speak my peace and then move on to the next obsession.

It’s easy to forget, but posting, replying to messages, and responding to comments is writing — it’s just piecemeal, inefficient writing that doesn’t go anywhere, is not read by very many people, and does not pay my bills. So I don’t do it anymore. If an idea is really worth exploring, it’s worth doing in a more formal piece of writing that will outlast the algorithm.

I resent humanity less.

I am far more patient with people now that I don’t have to respond to hundreds of random queries each day. There’s only so much energy you can give away to other people before you start viewing humanity as vampiric — even when the decision to offer up your lifeblood was entirely your own.

Reflexively, I often behave like I’m in a codependent relationship with the entire universe. It’s not a healthy impulse, but I come by it quite honestly — my dad treated me as a proto-therapist for my entire childhood, and as an awkward Autistic nerd, I learned early on that I could trick people into liking me if I made myself useful. I often feel responsible for everyone’s feelings, and take others’ crises as a personal call to action. Then I wind up drained and pissed as hell when, invariably, I prove incapable of fixing someone else’s life for them, or controlling their emotions.

Once you extend your empathy beyond its capacity, compassion fatigue sets in. It becomes difficult to care about other people or feel connected. I knew that I was absolutely screwed on this front once I began opening tender, appreciative messages thanking me for my work and feeling absolutely nothing about them. My heart had frozen over in order to protect me. It’s terrible, losing the ability to feel strongly for others. It’s like being half dead.

Now that I am not bombarded with dozens of messages every day (some of them lovely, some of them hateful, nearly all of them emotionally intense), I can actually show up for my real-life relationships. Instead of inviting people to make endless demands of my time, I’ve taken charge over where I direct my attention. I have no reason to resent other people anymore. My emotional limitations and boundaries are built into how I navigate social media.

I read (a LOT) more.

Just as posting on social media is writing, absorbing content on social media is reading — but it’s a chaotic, stressful, unfocused form of reading that never satisfies, and never provides you a pause to reflect. I got into writing because I adore reading, and the slow, languid periods of meditation and insight that come from curling up with a good book. But during the last couple of years, I wasn’t finding that kind of contemplative peace anymore. I was just scrolling all the time and getting stressed out over the same handful of unending, circular battles.

Ever since I shut down my comment sections and inbox, I’ve been sucking down books like they’re the day’s first cup of coffee. The Dawn of Everything by Graeber and Wengrow was dense and beset with tangents, but utterly paradigm-shifting. Brené Brown’s oeuvre is deeply flawed (especially when it comes to her unexamined fatphobia) but chock full of practical tips that will dramatically improve my next writing project. The Recovering by Leslie Jamison was gripping and impossible to put down. Beyond Shame by Patrick Moore transported me to a vitally important yet underexplored period of LGBT history, and then enriched my appreciation of ACT UP activism.

I could go on and on, but suffice to say: not reading direct messages and comments has freed up a TON of time for reading calmly splayed out on my yoga mat, or in the tub. My eyes are grateful for the break from blue tinged lights and my intellectually starved brain is eating well for the first time in ages.

I’m giving the apps less attention and advertisers less revenue.

Social media was designed to be addictive and enraging. There are numerous tricks the apps use to keep you using them more often and for longer than you’d like. For instance, have you ever noticed that when you first open Instagram, you’re briefly shown a post from one of your favorite accounts, which quickly disappears as the site refreshes, giving you no time to read or like it? Have you ever caught yourself scrolling through your feed, trying to “catch up” and find that disappeared post? I know I have! It happens to me a few times a week.

Yeah. That’s a deliberate tactic social media app developers use to keep your attention trapped on their apps. So is the non-chronological nature of the feed itself, and the presence of ‘suggested’ accounts. So is the tendency for the algorithm to boost controversial or offensive posts filled with active, contentious comment sections. So is the very existence of comment sections.

I’ve written about this before, but comment sections are a great way for social media sites to boost advertiser revenue. The more you get swept up in a fight in the comments, the more times you’ll return to the same page, giving the app more opportunities to try and sell something to you. And if you come to rely on a social media app as your primary messaging platform, well, that’s even more time with your attention that Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and all the rest can sell to advertisers for a hefty fee.

Facebook and Twitter have known for years that angry users are less judicious about how they spend their time, and more likely to get stuck refreshing the app over and over, firing off pissily little posts and getting distracted by arguments. They’ve even conducted experiments on non-consenting users to determine there’s an advantage to making people feel shitty. I know nothing makes me feel shittier on the apps that wading through a bunch of short-tempered infighting in my comment section.

For a long time it felt dirty, keeping comment sections open on my posts just for the sake of boosting their performance in the algorithm. Heavily commented-upon posts do get more attention. But all the extra “likes” I received came at the expense of my followers’ time and wellbeing. It also came at the cost of my own peace of mind.

I’m not interested in making that deal with the devil anymore. I’m willing to have my posts flop due to a lack of comments-based “engagement,” if it means I’m not feeding the irrational outrage machine. And I know that without comment sections and messages to read, I spend less time on the apps and feel far less anxious and angry, too.

I’m no longer encouraging people to form parasocial connections with me.

When you post a lot about yourself and your life online, people get attached to their idea of who you are. Sometimes, this is totally sweet and harmless. There are bloggers whose work I adore and follow with a fervent passion; I root for them when they say their life is getting hard, and throw money at their GoFundMe’s when they need bottom surgery or to have a tooth removed.

It’s nice to care about other people and feel bonded to someone through their creative work. But there’s is a big difference between harboring good will for a creator whose work you like, and having the illusion that you actually know them or that they are your friend. Unfortunately, social media makes it very easy to develop parasocial relationships with popular content creators, where a fan truly believes they know that creator well and could become actual friends with them. This is especially true if direct messages, comment sections, and ask boxes give users the illusion of closeness.

One time a few years ago, I followed along happily as a fruitful conversation about social justice language policing unfolded in my comments section. It was a civil, positive discussion, with people trading resources and nuanced ideas. In that moment I was proud of having created a space where people could hold such productive discussions.

About an hour later, a fight erupted on another post of mine — a Instagram slide set describing how “no cis men” event policies often prove hostile to trans women. The TERFs and transmisogynists were raging and brigading me, so I turned my comments off. A woman whom I’d never met popped into my private messages to express her disappointment. She said I was “shirking accountability” and “silencing the community” by turning comments off in this way. I could only laugh out loud at the absurdity of it all.

A digital following is not a community. There are no lasting relational bonds within a following list, no genuine social infrastructure, no healthy, horizontal methods of addressing conflict, and no means of remaining connected and invested in one another if the creator deletes their account. You might have a nice conversation in the replies of your favorite Twitter account, but that’s like having a nice chat after the concert of your favorite musician. Any additional relationship building and community development that comes from that brief moment of contact is on you. You may be connected by mutual fandom, but a network of fans is not a community — no matter how much a creator might profit off you believing that it is.

In a similar vein, there is no possibility for real ‘accountability’ within a mass-marketed social media space. My readers can comment and critique and gnash their teeth at my actions all that they like — but if I have no genuine, mutually respectful relationship to the people posting about me, there is no possibility of me restoring any bond that has frayed. There was never an actual bond to be frayed in the first place. It was just a fandom. A fan can stop following or supporting me whenever they like, but that action is nothing like an actual friend terminating a relationship. Most of the time, I won’t even notice that it’s happened.

I’ve started taking responsibility for the ethics of my digital actions.

Even though I’m only a niche microinfluencer, my writing is often quite intimate. My posts explore fraught issues related to gender dysphoria, trauma recovery, and the formation of a political and social identity. I also post images of my face and my pet, and share about the music I’m listening to and what I’ve been reading. I enjoy sharing my thoughts and experiences with the world, and people often appreciate consuming them.

But some followers project a lot of assumptions onto me, based on the limited information I reveal, and color in between the lines in ways that garner a false sense of closeness. When my DMs were still open, people would sometimes tell me outlandishly obsequious things — they’d claim my writing had saved their life, for instance, or said they feel like I understand them personally in ways no one else ever has.

If I were a more craven person, I could really turn perceived closeness that to my advantage. I could sell the ability to message me on Patreon, for instance, or create a Discord server that I brand as a “fan community” and charge access for it. I could accompany every post with a request for donations via PayPal or Venmo even though I have a full-time job and don’t need that income. I’ve seen numerous influencers do each of these things.

But I’m never going to do anything of that, because I find it disgustingly inauthentic and emotionally manipulative. I am happy to provide readers with information and entertainment. I post what I like, when I feel like posting it,b because I find the activity enriching and expressive. But I’m not going to use parasocial connections to line my own pockets or unduly expand my influence. If my ideas are strong enough, people will find and appreciate them — no exploitation or cajoling is necessary.

Ultimately, that’s the primary reason I have decided to close my direct messages and shut my comments down. When I had those lines of communication open, I was encouraging followers to view me as an endless resource, a freely available platform, and a potential friend, all in one. It is no longer realistic for me to give people those kinds of expectations. And it’s certainly not healthy for me.

I’ve reclaimed control of my boundaries and mental health.

I’ve been striving to establish healthier digital habits for a while now, and here’s one thing I’ve learned: boundaries are a thing you do, not a thing you force others to respect. Healthy, maintainable boundaries are all about the ways in which we control our own actions and reduce the ability of other people to harm or intrude upon us. This means that often, setting or protecting a boundary is about limiting your vulnerability to violation, and removing yourself from unsafe or painful places where your wellbeing is not respected.

The internet is not a safe or respectful place. Social media applications are forever on the hunt for new methods of manipulating us, and exploiting our energy, creative output, and attention. The temptation to overexpose ourselves will always be here — and rather than appealing to my own willpower or the judgement of strangers to help me resist it, I have decided to remove its siren song from my life as much as possible.

I’m going to leave comments open on Medium and Substack, where the feedback I receive is limited, thoughtful, and typically quite worthwhile. I’m also maintaining a Tumblr ask box, so that readers can submit questions for my advice column or suggest essay topics. But when it comes to Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram? That shit is on a strict lockdown, permanently. My mental health and writing time is far too precious to be wasting on social media junk data and endless, stressful intrusions.

Last night I had a really wild dream and at one point I was telling kids "community takes care of you even when they don't like you" 😄

Wonderful essay, again! It made me reflect a lot... I might do the same on my professional accounts someday, too 🧐 One can never be too reserved on the web, ah...