Your Fear is Dangerous & Your Power Is Greater Than You Think

How cops and the news media convince us to fear the vulnerable and underestimate our own power.

This piece was originally published to Medium on September 17, 2021. Why I’m migrating my archive to Substack.

As someone who believes in abolishing both prisons and the gender binary, one of the biggest misconceptions I encounter is the belief that certain groups are fundamentally “less safe" than others to be around. A lot of people mistakenly believe that the world is filled with dangerous predatory types, whom we can best understand using identity labels such as “male” or “superpredator” or “narcissist.” If certain groups of people are innately risky to be around, then we require police and enforced systems of gender segregation to ‘protect’ the vulnerable from them.

The argument that some groups are just plain dangerous takes a lot of different forms, and it targets many different categories of people. But no matter what shape it takes, this fear of the threatening “other” is almost always rooted in upholding the police state and reinforcing systems of unjust power. Here are a few examples of how it plays out:

I. The Fear of “Craziness”

People with mental illnesses are largely nonviolent, and in fact far more likely to be victims of an assault than to be perpetrators. The more visibly “mentally ill” someone is, the more likely they are to be homeless, unemployed, and lacking in legal rights. Despite the immense vulnerability of neurodivergent folks like these, hatred and fear of them are very deeply entrenched in our culture.

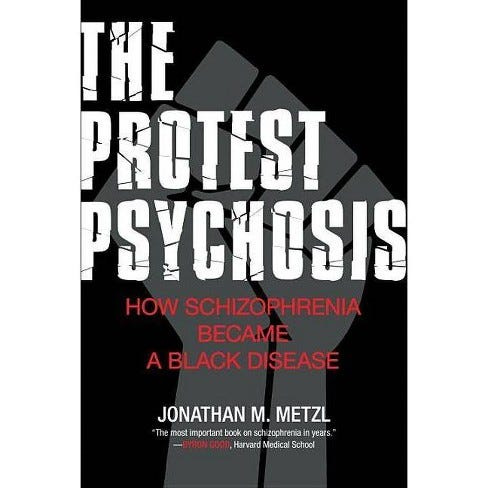

Our fear of the “crazy” has its origins in things like ugly laws, centuries-old statues from across Europe and the colonial Americas that meant anyone could be locked up if their behavior or appearance was unsightly or offensive to the public. In the United States, we also tend to criminalize mental illness for racist and political reasons: for example, Black revolutionaries in the 1960’s and 70’s were systematically described by psychiatrists as delusional and schizophrenic as a way to discredit them.

On countless television shows and movies, we see visibly mentally ill people portrayed as unpredictable and violent, sometimes almost animalistic, so out of control they supposedly require the police or an institution to forcibly reign them in. Historically, it is often the people whom the state wishes to control (such as socialists, gay men, and gender non-conforming women) who get labeled as sick, and therefore as dangerous. When we teach women and children the basics of self defense, we often instruct them to keep an eye out for anyone who is acting ‘strange’ (in other words, failing to conform) and we encourage them to trust their gut feelings — even when their gut feelings are simple prejudices against oddness. Juries also presume that signs of neurodivergence (such as avoiding eye contact) are signs of sociopathy or guilt.

As a former suburbanite who moved to a major city years ago, I remember how family members and teachers cautioned me to stay away from any people who acted a bit differently. I also remember how painful this messaging was to hear, as an Autistic person who has their fair share of twitches and tics. I realized I had to hide everything about me that might be seen as creepy or dangerous and to silence my inner spirit of nonconformity. When people are neurodivergent in public, they may be institutionalized, incarcerated, or shot. The risk of these outcomes is extremely elevated if they are a person of color, or visibly trans.

Here in Chicago, I regularly see people clutching their purses or beginning to dial 911 when a stranger begins talking to themselves or rocking in place. In my neighborhood, I have witnessed (and tried to intercede as) cops and security guards used violence and force to restrain people for having meltdowns or hallucinations that presented no threat to the public, only an annoyance. Their divergence, harmless as it was, made more powerful others feel unsafe. Privileged people’s feelings of unsafety created an actually unsafe reality for marginalized individuals.

The fear of mentally ill people is not rooted in reality. It’s not statistically supported or logical. Yet it is omnipresent, and even taught to many of us as a matter of good sense. The supposedly obvious “scariness” of the mentally ill continues to be used as a justification for demolishing mental health clinics in wealthy neighborhoods, and relocating or arresting homeless people whose encampments make gentrification difficult. It even is used to invalidate victims and those who speak out against injustice. “She wasn’t raped, she’s just crazy and wants to ruin his life.” “He’s being paranoid, he thinks everything is about race.”

It is our culture of fear and our prejudiced system of ‘protection’ that poses the true danger. Yet it’s very hard to get people to see this — or even to convince my fellow white suburbanites they shouldn’t call the cops the second a stranger says or does something weird on the street. The problem is, once state messaging and media stereotypes have convinced you a group is innately ‘dangerous’ to be around, that fact might seem so obvious to you, so common sense on its face, that to hear the perspective questioned might sound absurd.

II. The Fear of “Stranger Danger” Crime

Another place where people’s fears diverge from reality is in discussions of how innately violent cis men are. In particular, I hear a lot of white women claiming that cis men are well known to be far more dangerous than any other group, and that the world is in fact filled with violent men who might attack them on the street at any random moment. Because of this massive risk, it is necessary they be able to rely upon structures of power that will protect them.

I wish that people would interrogate this thinking a bit, and recognize it for the often racist, transmisogynistic dog whistle it can be. The fact is, “cisgender man” is not a coherent political category on its own. Nor is it a useful means for understanding where power comes from or how it operates. Ascribing danger or untrustworthiness to men who were assigned male at birth, rather than to the patriarchy, erases how vulnerable gender non-conforming and queer men are to violence, or how perilous it is to occupy public life as a man of color.

Lots of transgender men such as myself occupy a privileged position in society despite not being cis, and we have the ability to wield that power against others. The fact my genitals are different from a lot of other men doesn’t change the fact that my ideas are taken more seriously than women’s are. And the fact that someone is a man doesn’t mean they possess more power than a woman, either: after all, white women earn more money than Black or Latinx men, a fact all but ignored in most mainstream discussions about the pay gap.

When I raise these facts in queer, feminist circles, a lot of cis white women tend to become defensive or even outraged. It is an obvious fact, many of them will say, that men are more dangerous than women. Some men might be affected by racism or homophobia, but they are still men, and by and large, men do the greatest violence worldwide. They have good reason to fear men, they tell me, and they need ways to escape male violence. The danger of men is a statistical fact.

Hearing claims like these, I can’t help but ask how someone defines danger, or how they understand what constitutes violence. It is true, for example, that men vastly outpace women in terms of murder, physical assault, and sexual assault rates, as documented by the police. But therein lies the rub: our very understanding of who poses a threat, and even what a threat is, relies upon statistics created by a racist, sexist, militarized policing system. What the cops measure as a crime and how they measure it is a reflection of their priorities and goals. Crime statistics will never be a useful means for understanding how oppression works. That is because crime stats are themselves a tool of oppression, a metric police departments use to justify harassment and violence against men of color.

Our entire criminal justice system has a very narrow view of what constitutes violence. The types of harm that get documented by the police are things like damage done to property, and assaults that occur in public. When someone is brutalized or assaulted in private by a person that they know, the cops rarely get involved. When a parent neglects their child or beats them, the police state often has no means of knowing, and little incentive to do anything about it.

Impoverished, majority Black neighborhoods are also over-policed, meaning that crimes are far more likely to be observed and documented there, whereas similar incidents in white and suburban neighborhoods may never get recorded. Men of color are more likely to be stopped and frisked, or to be pulled over by the cops, vastly amplifying their arrest rate. They are less likely to be let off with a warning for small offenses, and are more likely to be convicted when tried with a crime.

These patterns all dramatically distort our crime statistics, our sense of which places are safe to inhabit, and our public myths about which people are dangerous to be around. It is very interesting and telling, then, those white women will frequently use crime statistics that target Black and brown men as their “evidence” that all men are unsafe, or that the world is unsafe. They might be unwilling to explicitly endorse any claim that men of color are dangerous, but by supporting police statistics that are built on that assumption, they are feeding into it.

The over-inflated ‘danger’ presented by men of color is used to cultivate a powerful, isolating fear in white women. And like the fear of mentally ill people, it does not line up with their actual susceptibility. White women are at a very low risk of violence committed by strangers or out in public. When white women are attacked, they are more likely to be helped and to be able to access emergency services. Despite the low-risk white women face, the cops and the news media play up the supposed danger that men, particularly Black men, pose to white women, and place a great deal of focus on the (very rare) cases of white women being attacked.

III. The Fear of White Female Victimization

Most white women are unaware of the fact that they are at very low risk of violence, relative to both men and women of color. In fact, they tend to believe the crime rate is far higher than it actually is. Fear of crime and the actual crime rate has almost no relationship to one another. That’s because media messaging and cultural upbringing have a much bigger influence on people’s risk perception than anything else. And white women are taught by their families, friends, and teachers that they are fragile and vulnerable. They are instructed to carry pepper spray, hold their keys in their hands, and never walk home alone at night — even if that means staying alone at home with a man who might be farther likely to attack them.

White women are conditioned to fear the outside world and to reach for police aid the moment someone makes them uncomfortable— despite the fact that the police are notoriously terrible at supporting victims of things like domestic violence and rape. In this way, the fear of violent crime at the hands of strange “men” is both a tool of racism and a tool of the patriarchy. It convinces white women that rather than fighting against the systems that oppress her, she should appeal to those systems to protect her from even less empowered people.

When a white woman calls the cops on a man of color who has done her no harm, she is committing a violent act. When “Karen” reports a Black barbecue to the police or demands an armed security guard take away a Black woman’s phone, she is using state power to endanger the lives of marginalized people. These are acts of racist aggression with a real body count. Yet acts like these never appear in any crime statistics. When we are trying to appraise how dangerous a person is, or a community might be, we rarely include indirect, pernicious forces like these. We also don’t include the police murder of Black civilians in our murder statistics.

Racist crime statistics that unfairly depict Black and brown men as dangerous are frequently evoked by white women to justify their fear of men and their need for powerful structures of defense (such as prisons). Yet Black and brown men are rarely permitted to point out how dangerous white women are to them, or to ask for spaces safe from it. Men who experience domestic violence, sexual assault, or emotional abuse are unlikely to report it to anyone for similar reasons — their experience flies in the face of how we have been taught to understand danger, power, and violence.

Many forms of violence and abuse go undocumented by our criminal justice system because they happen quietly in the shadows of our prevailing power structures. Is it violent to verbally berate a romantic partner for years and destroy their self-esteem? When a parent kicks their queer child out of the house, is that violent? Is forcing your daughter to go on a diet when she is a pre-teen an act of violence? Is getting a trans woman arrested for using the restroom violence? Is it violent to get a Black female coworker fired because she seems “angry” to you and you feel “unsafe” around her? There are so many forms of abuse and cruelty that never even register for us when we rely upon the police state’s definition of “crime.”

IV. The Fear of “Male Violence”

When we understand danger as coming from specific, unchanging identities, rather than intersecting structures of power, we also tend to perpetuate transmisogyny, the structural oppression of transgender women. A lot of trans-exclusionary women point to their fear of dangerous “males” as a justification for excluding trans women from public life. They claim that by virtue of their bodies, or by virtue of their supposedly “male” histories, trans women can never understand sexism, and will always wield a power they, as “female” people, cannot possess.

But this belief system is not exclusively the purview of TERFs. Even people who claim to be trans-affirming unwittingly feed into the same ideology, creating gender-segregated spaces that are billed as being for “everyone but cis men,” but which in practice are hostile to anyone who is read as physically masculine. There is an assumption embedded into “anyone but cis men” policies that are really quite nefarious: it implies that anyone who was assigned female at birth is safe to be around, no matter their identity or status. Conversely, any person who was assigned male at birth and hasn’t loudly disavowed that label (despite how risky disavowing that label is) is seen as suspect. It creates an asymmetry that disadvantages trans women and makes their womanhood something they must prove.

Cis feminists also perpetuate transmisogyny by dabbling in talk of how “female socialization” makes women safe to be around and makes men entitled and predatory. The truth, of course, is far more complicated: white people are socialized into entitlement and privilege in many ways, for instance. Men of color don’t move through the world with the ease white men do, so to call their socialization equivalent is nonsensical. Many trans women spend their whole lives not being rewarded for ‘manhood,’ but being severely punished for failing at masculinity. And I can’t tell you how many times I have seen a trans man speak over a woman or invade her personal space, only to scoff at the notion he might be sexist, because hey, he was ‘female socialized.’

Of course, there are a lot of reasons to create gendered spaces beyond superficial beliefs about ‘safety.’ When I was leading workshops that helped trans people practice self-advocacy, I intentionally made the events trans-only. The skills I was imparting were for trans people — there was no need for cis folks to be there. Even still, branding the event as “trans only” did not provide any guarantee the space would be free from transphobia, or that it would be innately “safe.” Trans people can do plenty of abusive things. White trans people can be deeply racist to trans people of color. Trans men can be sexist to trans women. Hell, many of us are just downright transphobic to one another.

This is yet another problem with the belief that certain classes of people are fundamentally safer than others: it ignores the fact that systemic forces of oppression affect each of us, and that no one is immune from absorbing them. Women experience sexism and objectification, yet it has been the women in my life who have tended to be the most invasive and predatory toward me and my body. Queer people are the targets of homophobia and transphobia, yet we frequently enact those biases ourselves. Just look at the fact that Cara Delevinge, a bisexual woman, wore a homophobic “Peg the Patriarchy” top to the Met Gala last week. She might be queer, but she still intentionally called forth the idea anal sex is degrading and disempowering. She also stole the slogan of a woman of color in the process, by the by.

Women Who’ve Told Me How My Body Should Be

Women have been responsible for some of the most body-shaming, objectifying, sexist experiences of my life.

The Power That’s Hidden

Our identities do not absolve us of the capacity to do harm or abuse authority. Power and danger are not just issues of who we are (or what we are), but also the authority we hold over the lives of others. A queer woman in a management position has the power to fire her employees and deprive them of the means to eat and pay rent. A white female professor has power over her students and can abuse it by making sexually inappropriate comments. A person who grew up in poverty can go on to become an exploitative corporate tycoon. Since these systems and our relationships with them are so intersectional and mutable, it makes no sense to understand danger or threat as crystallized within a single identity alone.

Unfortunately, most of us tend to be hypersensitive to the ways in which we are vulnerable but relatively oblivious to the ways in which we wield power over other people. Unjust systems of power work best when we fail to notice them at all. Part of why white women have historically been such effective enforces of white supremacy is because they believe themselves to be so weak.

When they view themselves as hyper-vulnerable, white women have reason to cling to white male systems of power (such as the police and generational wealth). The less ‘safe’ they feel, the more they will invoke external power in order to protect them. This is also why transphobes constantly need to reinforce the supposed threat of “males” in women’s restrooms, gyms, and competitive sports. They need to convince cisgender women that they are under attack — even while trans women experience a far greater risk of violence than they do, by every metric.

Our fears and feelings of unsafety are not objective indications of reality. Far too often, they are just reflections of our culture’s biases. And by and large, the people who are branded as the most ‘scary’ — men of color, people with mental illness, and trans women — are in fact the people who experience the greatest risk. If we are to end the oppression of these marginalized groups, we will need to help people overcome their irrational fears, and dispel pernicious myths about where violence comes from, or how it ought to be defined. We’ll also need to help people learn to recognize their own power — so that they might use it to fight oppression, rather than turning it against one another.

Thank you so much for writing this. I have so much to think about. As a white woman I have absolutely been guilty of so much that you describe. I don’t think I realized it was because I believed I was weak. I felt like I was operating from a personal perspective with a history of abuse from men. I don’t know how to process that in this framework or decouple that yet.

Amazing article. Thank you for this essay. I think fear is such a strong emotion that drives people to conformity, and then perpetuates belief systems of fear, a vicious circle . So much to think about from your essay and from my own experiences. Thank you for sharing this. I think if ‘we’ ( anyone living in cultural fear of someone who is different to themselves ) are unable to uncover their own fear biases it may led to changing belief systems, away from fear and toward kindness and acceptance...which might, just might help dismantle the colonial patriarchy and power structures...