A Nation of Settler Militias

What "An Indigenous People's History of the United States" by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz teaches us about the genocide happening today.

I have been reading a lot about Indigenous history lately. It’s been a major area of interest of mine for some time, for both personal and political reasons, but it seems even more essential to study during Israel’s ongoing genocide of the Palestinians.

The United States’ genocide of Indigenous peoples parallels the forcible displacement, cultural erasure, and murder of Palestinian people by Israeli settlers to an absolutely eerie degree. And in the study of past Indigenous movements of resistance, we can learn lessons about how we all might oppose violent settlement now, and what a post-colonial life on this planet could look like.

Learning about the many diverse Indigenous cultures that exist on this continent and abroad fills me with hope and a sense of possibility for humanity’s future. Grappling with the violence that has been wrought against native peoples is clarifying to me, and gives me purpose, even when fighting against an oppressive government seems impossibly hard.

There have always been people on this earth who have cared for one another and the land, who have not believed in the moral righteousness of conquest, who have traded food and traditions and embraced the displaced as their own, and there always will be. Every single moment that we are alive, we get to choose whether to align ourselves with these peoples and their ever-evolving, vibrant ways of life — or to keep up with the deadly daily grind of colonial capitalism.

For all these reasons, I recently picked up a copy of Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s excellent book, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. A coworker named Udayan had leant me a copy several years ago, but at the time, when I started reading it, I just wasn’t ready to fully absorb its message. I hadn’t gotten interested in leftist anarchy yet, and hadn’t done a lot of the deep reading about white supremacy and the building of nation-states that I now have.

I wouldn’t have described myself in this way, but at the time, I was very much still a moderate liberal who believed in the potential of the United States government to reform itself into something livable and basically just. I could not imagine a life that wasn’t under the thumb of the United States government, with a military that enforced its borders and kept children and suspected “terrorists” in cages. I hated so much of what the government was doing, but feared living in a world of total “anarchy.”

I almost exclusively went to protests that were peaceful and permitted. I believed the government benevolently gave me the ‘right’ to do the things I wanted with my body, and that if I didn’t pledge my allegiance to the correct politicians and beg them ardently enough, I’d deserve it if they took those ‘rights’ away. I saw no way to influence my political reality except by calling Senator’s offices, sending form letters, and volunteering for the campaigns of politicians I didn’t really agree with.

Leave Non-Voters Alone

Non-voters aren’t lazy or apathetic, they’re victims of systemic injustice. devonprice.medium.com

I was also working through some complicated, annoying, white-person hand-wringing feelings about the Indigenous ancestors of mine who had chosen to assimilate into whiteness many years ago, leaving their people behind. Or at least, that was my view of them back then.

Now my outlook is quite different, and my understanding of history goes a bit deeper. I was prepared to really understand the evils of the American settler-colonial project in full this time around, and to confront that little of this country is worth salvaging.

With this read through of Dunbar-Ortiz’s book, I was completely blown away, and radicalized all the more. I unlearned so many intentionally confusing myths about what America is and how it came to be within the book’s 300 pages.

I came to understand that this is a country created by settler militias, not by immigrants, and that moral culpability for the harm done by the U.S. goes a lot farther than just a handful of wealthy slave-owners and especially badly behaved soldiers.

I learned about how the U.S. government’s political repression of Native peoples set a legal precedent that would one day be used to justify the torture of suspected “terrorists” at Guantanamo Bay and in Abu Ghraib. I saw more parallels between the violent settlement of the U.S. and of Israel than ever.

Mistrial: Abu Ghraib Survivors Detail Torture in Case Against U.S. Military Contractor

A historic case against U.S. military contractor CACI brought by three Iraqi survivors of torture at the notorious Abu Ghraib prison. www.democracynow.org

More than anything, Dunbar-Ortiz’ book taught me that the colonization of the United States relied upon the committing of several key sins — uniquely cruel political and military innovations that would reverberate forward throughout history, changing everything about how warfare is conducted and how oppressed peoples are exploited across the globe.

The fundamental sins of American conquest are: gun “rights”, private property, factionalism, and irregular warfare against “unlawful enemy combatants.” In this piece, I will discuss where each of these sins came from, why they were so essential to a successful Indigenous genocide, and the legacy we continue to see from them today:

Gun “Rights”

As an American, I had grown up being taught that the “well regulated militias” of the Second Amendment had arisen to fight off the British soldiers during the war of independence.

Under this version of United States history, citizens retain the right to own guns so that we might defend our property from criminals, protect “our” territories against foreign invasions, and resist tyranny from federal government. To this day, Americans evoke this interpretation of the Second Amendment as a justification for concealed carry rights, and for “castle doctrine” laws that allow home owners to shoot intruders (even unarmed ones!) inside their homes.

In reality, the militias mentioned in the Second Amendment had formed many decades before the revolution, and were initially created to slaughter Indigenous people and clear them out from their lands. The foreign “invaders” that the Second Amendment was created to defend against were not the British colonizers, but the many Native peoples who had been living on Turtle Island for thousands of years before European conquest.

Dunbar-Ortiz writes:

“…Native peoples are implied in the Second Amendment.

Male settlers had been required in the colonies to serve in militias during their lifetimes for the purpose of raiding and razing Indigenous communities, the southern colonies included, and later states’ militias were used as “slave patrols.”

The Second Amendment, ratified in 1791, enshrined these irregular forces into law: ‘A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.’”

Until reading this book, I had no idea.

Even in political commentary that is critical of gun rights, it is taken as a given that the Second Amendment came into being because American revolutionaries needed to defend themselves against the British army. We aren’t at war with a colonial empire anymore, gun control advocates argue, so we don’t need to maintain civilian armies on U.S. soil.

Why don’t these gun-control advocates explain that civilian armies only came into being to engage in genocide? Certainly the militia’s history of roving across Indigenous land, slaughtering men, women, elders, and children, burning up food stores, conscripting individuals into enslaved military service, and marching tens of thousands of people into open-air prison camps at the barrel of a gun was an even better argument against unregulated gun rights?

Dunbar-Ortiz writes:

“From the colonial period through the founding of the United States and continuing in the twenty-first century, [genocide] has entailed torture, terror, sexual abuse, massacres, systematic military occupations, removals of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories, and removals of Indigenous children to military-like boarding schools.”

She also cites scholar Patrick Wolfe, who emphasizes that the violence of colonization was not only at the hands of an organized government military — small bands of armed settlers formed their own militias to proactively massacre Indigenous people, even when the U.S. government did not want them to:

“…The peculiarity of settler colonialism is that the goal is elimination of Indigenous populations in order to make land available to settlers. That project is not limited to government policy, but rather involves all kinds of agencies, voluntary militias, and the settlers themselves acting on their own.”

For a halfway-aware student of history, the case to be made is not that the Second Amendment is no long relevant to modern life, but that it’s very reason for existence was one of unchecked, unjust, racialized violence, and that we’d better off doing away with the whole thing. And yet no one in all the years that I have been reading about and pondering the social problem of gun violence has ever brought up gun rights’ genocidal origins.

This shows just how profoundly the United States is committed to erasing its past, and how little the perspectives of Indigenous people are still listened to. I am ashamed that I grew up believing a complete lie about the reason for gun rights’ existence, and so grateful to the scholarship of Dunbar-Ortiz and her colleagues that I finally know better.

As a person who firmly supports individual autonomy and as a pretty outspoken opponent of the nation-state, I have generally supported the freedom of other people to own guns, even while finding guns terrifying myself.

I am aware that the penalties for violating any law restricting gun access will fall most harshly upon Black and brown people, and that gun restrictions might not prevent mass murders and white supremacists from toting them here, because it’s such a large, interconnected continent and so many weapons are already freely circulating. I’ve considered the legacy of the Black Panthers and the Pink Pistols with admiration, and thought that any revolutionary party in the United States would need access to munitions, because the military would attempt to suppress them with violent force.

But this book has given me pause.

Guns killed the Indigenous people of this land in massive numbers. Over a dozen Native nations had been ethnically cleansed by settlers by 1846, writes Dunbar-Ortiz. By 1870, settlers had killed more than one hundred thousand Indigenous people in what is now known as California.

The peoples that remained alive during such armed sieges and had to flee toward the American west, and frequently became dependent on guns in order to hunt bison and buffalo. Dunbar-Ortiz writes that they received munitions from American merchants through predatory lending schemes that drove many Indigenous nations into terrible debt. Many peoples wound up losing even more of the land they used for living, farming, and hunting because they had to sell it back to the United States in order to pay those debts off.

The gun has historically not been a tool of liberation but one of colonization, often in the hands of random settler colonists who took it upon themselves to expand the borders of the growing empire. Many of these civilian militias later became “slave patrols,” chasing after escaped Black people, and then later, the cops.

Contending with this history forces me to rethink whether guns are truly beneficial to have. And it reinforces for me just how rotted white, settler-colonial American culture is at its core.

So many white Americans participated in the Indigenous genocide. Virtually every white man living on the continent in its early decades could be conscripted into killing native peoples at any moment, and tens of thousands of settlers charted a course from England to Turtle Island with the specific purpose of driving Indigenous people off of land by force so they could take it for free.

Many white Americans comfort ourselves by saying that our families never took part in slavery, even if it’s only because they lived in the wrong area for it, or they were too poor to. That doesn’t mean they didn’t economically benefit from slavery or that they didn’t want to purchase human lives, but we reassure ourselves that hey, at least they didn’t. We tell ourselves our great-great grandparents fled their countries seeking freedom from religious persecution, or starvation, and eked out a modest survival here, and that they were blameless while the country committed genocide.

The reality of the historical record challenges that notion. Escaping poverty or persecution abroad required that a colonist be willing to pick up a rifle and kill brown people for it. And many settlers gleefully participated, collecting dozens of blood-stained scalps to sell for cash and social clout. Dunbar-Ortiz writes:

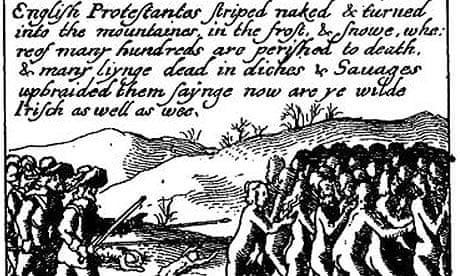

“The English government paid bounties for the Irish heads [in the sixteenth century]. Later only the scalp or ears were required. A century later in North America, Indian heads and scalps were brought in for bounty in the same manner.

…Scalp hunting became a lucrative commercial practice. The settler authorities had hit upon a way to encourage settlers to take off on their own or with a few others to gather scalps, at random, for the reward money.”

This was not a grudging genocide. Committing gruesome acts of extermination is an indelible part of who we are, collectively, as a nation. And we must contend with that reality fully if we ever wish to overcome it.

Private Property

Throughout An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, Dunbar-Ortiz acknowledges the economic and political factors that transformed so many down-trodden European peasants into active drivers of genocide. It was the Irish who were first run off their homelands and rounded up in reservations, after all:

“The ancient Irish social system was systematically attacked, traditional songs and music forbidden, whole clans exterminated, and the remainder brutalized. A “wild Irish” reservation was even attempted.”

Being victims of genocide at the hands of the English did not prevent Irish settlers from becoming perpetrators of that same kind of violence against Indigenous Americans. In fact, it was their forcible displacement from their homes that made them such effective tools of military conquest.

Learning this gave me considerable pause, too. I hadn’t realized that such a direct line connected the end of feudalism in England to the beginning of settler-colonialism abroad. As it turns out, the invention of private property and the enforcement of private property laws are one of colonialism’s original sins.

As Dunbar-Ortiz explains, many English peasants once lived on the commons, public lands where they could farm, build cottages, trade, fish, raise animals, participate in cultural practices, attend church, and so on together, in small interdependent communities. “Commoners” benefitted from the land being a public resource rather than private property. They worked eight hours or less on average per day, and spent about five months of the year celebrating, feasting, and honoring holidays.

If these gatherings of commoners sound similar to the communities many Indigenous Americans enjoyed prior to colonization, that’s no coincidence. Many peasants and commoners were the descendants of Indigenous Bell Beaker and Celtic people, who had been driven off their land, forced to abandon their language, converted to Christianity, and economically oppressed by invading Europeans. Many of their great-great-grandchildren would one day do the same to the Indigenous people of the Americas when they were once again displaced from the Commons.

The creation of private property is what set everything into motion. The commons were abolished, the land the peasants had lived on for generations divvied up and all control over them handed to wealthy lords.

Dunbar-Ortiz writes:

“During [the sixteenth century], peasants, who constituted a large majority of the population, were evicted from their ancient common lands.

For centuries the commons had been their pasture for milk cows and for running sheep and their source for water, wood for fuel and construction, and edible and medicinal wild plants.

Without these resources they could not have survived as farmers, and they did not survive as farmers after they lost access to the commons.”

Many of the small farms that commoner families had maintained were converted to nothing but decorative grass, a demonstration that the lord owning that land was so wealthy they didn’t need to use all they owned productively. This was the beginning of the modern-day lawn; American home-owners fancy themselves small-scale lords, in a sense, when they maintain beautifully manicured, ornamental lawns today.

The expulsion of the peasants from the commons began a chain reaction of settlement, violent clashes, economic displacement, and genocide that shaped the world we live in today. The peasants were now hungry, unhoused, detached from their broader communities, unable to practice their cultures, and forced to work wage-earning jobs for far longer hours in return for far too little pay — and that’s if they could get work at all.

The Scottish Lowlands had been colonized by Britain long before Ireland was, sending tens of thousands of Scottish settlers relocating to northern Ireland. There, they displaced the Irish people, stole their land by force, and exerted a strong Calvinist Christian influence that the Catholic Irish strongly resisted. This forced mass migration in turn flowed into migrations to what is now the United States. Scots-Irish were the majority among the white settlers seeking to dominate the continent, slaughtering Native Americans in massive numbers, and establishing strong religious and political roots.

One wave of displacement cascaded into the other, creating an ongoing rush of settlement and violence. Economically displaced, politically wronged people like the Scots and then later the Irish crashed into other groups, and wronged them in turn. Each of these disenfranchised groups were regarded as almost disposable by the imperial powers that had created them — which made them excellent soldiers in the fight for American land.

Dunbar-Ortiz writes:

“Employed or not, this displaced population was available to serve as settlers in the North American British colonies, many of them as indentured servants, with the promise of land. After serving their terms of indenture, they were free to squat on Indigenous land and become farmers again.”

When we white Americans like to imagine our ancestors blameless, we remind ourselves of these facts. Irish-American people love to remind Black and brown Americans that they were oppressed, too, and lived through a prolonged cultural genocide, for instance. Those that romanticize the United States’ origins point to the religious repression of the Puritans. I have often soothed my own settler’s guilt by thinking of the profound poverty of my Applachian relatives.

We are not wrong to bring these facts up. They can remind us that the exploitation of poor white people is inherently of a piece with what Indigenous people, Black people, Palestinian people, and all other displaced, marginalized groups experience.

The lesson here is not that white settlers can be excused their violence because they have suffered. The lesson is that suffering does not grant a person moral righteousness, and that economic powers and large governments will attempt to use one group of poor people as pawns against the other whenever they get the chance. Powerful lords and wealthy politicians will convince the settler that the native person is their enemy, enlist native people to fight to defend slavery, and do all that they can to prevent unity across diverse groups of exploited peoples, to keep the crowds from banging on their doors and their own heads from winding up on a spike.

It was the creation of private property that generated so many starving, land-hungry settlers who were willing to kill Native people in order to become subsistence farmers once again. But it was political and racial factionalism that kept various displaced groups divided and warring with one another, even as wealthy land-owners and industrialists continued to take advantage of them.

Factionalism & Racism

Following the creation of private property and the dissolving of the commons, England also began industrializing, with technology streamlining many aspects of commercial production that had been previously done by hand. Industrial technology meant that fewer laborers were needed to complete tasks like spinning wool or harvesting grain, at precisely the time when thousands of displaced farmers were desperately searching for paid work.

The sheer number of impoverished people in England who lacked housing or employment posed a threat to the wealthy lords of the country, who feared rebellion. Sending settlers overseas with the promise of free land was not only an effective way to beat back the American “wilderness” (and the Indigenous peoples who lived there), it was also a great way to cull the number of enraged peasants who were sitting on English soil.

Dunbar-Ortiz writes:

“…Surplus labor created not only low labor costs and great profits for the woolens manufacturers but also a supply of settlers for the colonies, which was an “escape valve” in the home country, where impoverishment could lead to uprisings of the exploited.”

When poor Scots-Irish people first came to the American colonies, they frequently did so as indentured servants. They lacked many freedoms during their period of servitude, and in this respect shared some economic and political circumstances with the enslaved Africans who had been forced onto the continent. However, they had already been conditioned to consider themselves inherently superior to other racial groups.

As settlers of Ireland, after all, the Scots-Irish had already been paid to collect the scalps of Irish people, whom English scientists of the era viewed as less human and closer to “apes.”

Still, the indentured servants of the American colonies did recognize a common thread connecting themselves to enslaved African people. One of the clearest signs of this occurred in 1676 during what’s now called Bacon’s Rebellion, in which both white indentured servants and enslaved Black people banded together to slaughter Indigenous farmers, in a bid to take over their land in modern-day Virginia.

This siege was not authorized by the colonial government, and it demonstrated the collective power white and Black laborers had when they worked together (albeit for genocidal ends). If indentured servants and slaves could use their own military might to take land for their own whenever they wanted, the colonial government would no longer be able to control them and force them to work.

And so, to prevent this from happening further, the colonial government took steps factionalize white servants from Black enslaved people and make them view each other as opponents, not allies. Dunbar-Ortiz writes:

“The plantation owners who ruled the colony were troubled, to be sure, by the interracial aspect of the uprising. Soon after, Virginia law made greater distinction between indentured servants and slaves and codified the permanent status of slavery for Africans.”

From this point forward, Black people in the colonies remained enslaved for the whole of their lives, with their legal owners also holding ownership over all of their children. Chattel slavery became strongly differentiated from mere indentured servitude, and the differences in legal status only reinforced the racism that would otherwise keep poor white and Black laborers apart.

Factionalism proved a powerful political defense against rebellion again and again, as it already had in Europe. British colonial leadership often pitted Native nations against one another, forming alliances they did not honor after the battles were over.

The Puritans in Plymouth, for example, had joined forces with the Narragansett against the Pequot, dwindling Pequot numbers from 2,000 to a mere 200. The Narragansett had traditionally approached war as an honorable, rule-guided process that minimized causalities, and were disgusted by the cruelty of the Puritans. A few years later, the colonists took the side of the Mohegans in their own war against the Narragansett.

Europeans continued offering alliances with Indigenous nations throughout colonization — on both the British and American sides during the revolution, on both the Union and Confederacy’s sides during the Civil War, and in wars against rival Indigenous groups. This often exposed Indigenous forces to further violence while spreading them thin and exploiting them as a source of military might that the colonial power didn’t have to pay. From the Indigenous people’s perspective, aligning with the least objectionable of your enemies often made good sense. But as a prolonged strategy of settler-colonial warfare, it only reduced Native numbers.

Many of the Indigenous nations who retained numbers and autonomy for the longest did so by aligning with the colonial powers and assimilating into European culture in some way.

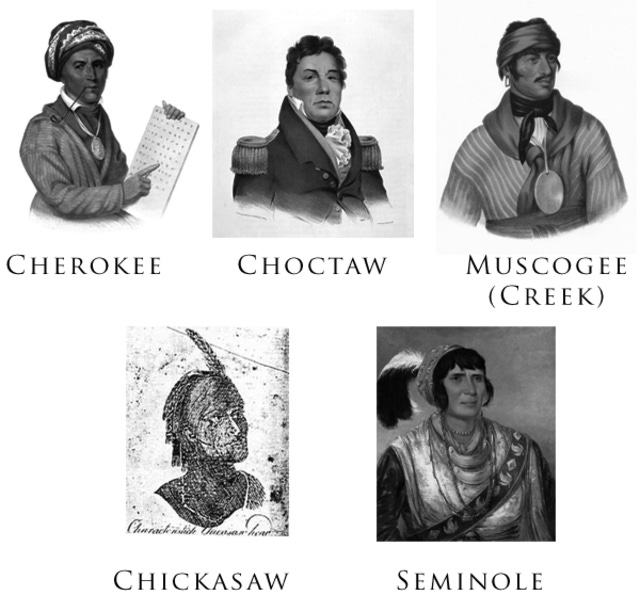

The so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” — the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Cherokee, and Muscogee (Creek) — were deemed such by the American government because of their willingness to participate in trade, European-style agriculture and crucially, slavery. Though Dunbar-Ortiz qualifies that the practice was relegated only to a handful of the extremely wealthy, members of most of these nations (other than the Seminole) did own enslaved Black people.

To this day, the descendants of these enslaved peoples cannot join tribal registries for the nations that they helped build, and face regular discrimination within Indigenous spaces. (To learn more about their experiences and modern-day advocacy, check out the Choctaw and Chickasaw Freedmen Association).

One Indigenous group whose legacy illustrates the power of resisting racial factionalism is the Seminole people, a community of Muskogee war refugees who welcomed displaced survivors from other Native cultures, as well as enslaved Black people who had fled plantations for Florida. The word Seminole comes from a Muskogee word, simanó-li, which means “runaway” or “outcast,” and their culture is a testament to Indigenous community and cultural evolution during times of gruesome warfare.

Dunbar-Ortiz writes:

“The Seminole Nation was born of resistance and included the vestiges of dozens of Indigenous communities as well as escaped Africans, as the Seminole towns served as refuge…in the United States the liberated Africans were absorbed into Seminole Nation culture. Then, as now, Seminoles spoke the Muskogee language, and much later (in 1957) the US government designated them an “Indian tribe.”

Like the Métis and Melungeon peoples, who welcomed European fur trappers, poor laborers, escaped Black people, and other Indigenous nation’s members into their communities, the Seminole actively resisted the racial divisions that have proven so convenient to settler-colonization.

But the settler-colonial United States continued to separate marginalized groups using the tool of race: by introducing blood quantum requirements for tribal enrollment, multi-racial Native people and those who lacked documentation of their lineage became unable to formally join their tribes.

Historically, what defined a person’s Indigenous identity had always been their relationship to the land, its people, and their culture, and it had often been possible for a person to join a different nation based on adoption, cultural sharing, or migration. However, once the United States identified Indigeneity as a biological race, this rich cultural history became far harder to preserve, and the number of legally Indigenous people dwindled — by design. In order to count as truly Indigenous, a person had to possess enough Native “blood.”

The United States identified Blackness in the exact opposite way: “one drop” of Black racial history disqualified a person from counting as either white or Indigenous. This also prevented generations of Black Indigenous people from being recognized as members of their nations.

Just as Black and Indigenous racial identities were tools of colonization in the United States, Arab and white racial identities have been used by the settler-colonial state of Israel to deny Indigenous Palestinians political representation and freedom.

Arab racial identity was constructed to cast Palestinian people who had lived in the region all their lives, including Jewish ones, as interlopers who did not actually “belong” there. And the Zionist project of creating Israel in the 20th century was explicitly an ethnonationalist one, with entire racial groups excluded from citizenship for many years — just as Black and Native people were prevented from participation in U.S. politics for the majority of the country’s existence.

But there was one more major political tool that the modern state of Israel borrowed from the United States in accomplishing it settler-colonial ends. In addition to the use of armed settler militias, private property, and racial factionalism, both Israel and the United States have relied upon irregular warfare tactics lobbed against anyone they deemed an “unlawful combatant” — in other words, a legal nonperson.

Irregular Warfare against “Unlawful Combatants”

The legacy of the United State’s slaughter of Indigenous people can be found in our conception of terrorism, and the legal status of “unlawful enemy combatants” which has been used to justify torture, murder of civilians, and long-term imprisonment without charges every being placed.

Dunbar-Ortiz explains directly how the modern-day conception of ‘terrorist’ originated in how American settlers viewed Native peoples fighting to preserve their rights:

“Settler colonialism is a genocidal policy. Native nations and communities, while struggling to maintain fundamental values and collectivity, have from the beginning resisted modern colonialism using both defensive and offensive techniques, including the modern forms of armed resistance of national liberation movements and what now is called terrorism.”

European settlers used a variety of war tactics with the goal of completely eradicating Indigenous people, adhering to no formal rules of war. They burned villages and cornfields and financially rewarded the scalping of children and elders, alongside adult warriors. They destroyed energy stores and encampments and hunted bison and buffalo to near extinction, leaving their bodies out in the sun to rot rather than bothering to harvest their meat. They attacked peaceful villagers who had surrendered, signed treaties pledging peace and then violated them, crossed territorial boundaries and utilized extreme violence, starvation, and torture that would have shocked even their adversaries from other European countries.

To defend themselves against such all-out genocidal war, Native peoples relied frequently upon guerilla war. They struck the colonial military quickly, in small numbers, using their intimate knowledge of the land to hide and then beat a hasty retreat. They aligned themselves with whomever seemed least likely to complete a total genocide against them: the British monarchy instead of the American settlers, then the Confederacy, in hopes that a divided United States would become less powerful. All of this was taken by settlers as evidence of Native people’s treachery, and they retaliated with even more pronounced violence.

Dunbar-Ortiz explains how the mastery of irregular, genocidal warfare tactics helped prepare the U.S. military for waging self-serving “wars” all across the globe:

“Although US imperialism abroad might seem at first to fall outside the scope of this book, it’s important to recognize that the same methods and strategies that were employed with the Indigenous peoples on the continent were mirrored abroad.

Between 1798 and 1827, the United States intervened militarily twenty-three times from Cuba to Tripoli (Libya) to Greece…

US colonies established during 1898–1919 include Hawai’i (formerly called the Sandwich Islands), Alaska, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, the Marshall Islands, and Northern Mariana.”

Before reading this book, I hadn’t realized just how much of America’s military history was informed by the genocide of Indigenous people. The genocide of Native peoples is taught in United States’ schools as a near accident (as if we didn’t spread smallpox and deprive people of food on purpose), or a necessary evil that simply ‘happened’ as large towns of white people casually “pushed” others off the land.

By the time most Americans are adults, we grow to understand that what happened to Indigenous people was actually genocide, and that it was awful. But we don’t examine the intentionality and prolonged nature of the carnage that occurred. This country’s primary military “enemy” was Native people. Settlers warred tirelessly against the Indigenous for over three centuries.

Nor do we take the time to appreciate how centuries of hunting thousands of cultures to near-extinction warps the world we live in today.

The U.S. military saw the Indigenous peoples as insurgent foreign adversaries, and once the end of the west coast was reached, the march against foreign adversaries continued — to the north, where Alaska was taken, and out into the oceans, where Hawaii, Guam, the Marshall Islands, and most of Latin America were claimed.

The military by this point was robust and well-trained in terrorizing local peoples, whom it viewed as hostile and having no right to occupy the lands that they had always called home . And so it continued using its genocidal tools, establishing bases worldwide, converting the survivors of its assaults to capitalism and Christianity.

The tactics mastered on Turtle Island in the 18th and 19th centuries were exported to places like Panama, Vietnam, Korea, and Iraq in the 20th. The tactics used on the Trail of Tears inspired the police kettling protestors and beating them to a pulp today. The reservations in the American west became the modern prison camp of Gaza.

The geography of the United States is shaped by its centuries-long war against Native “insurgents.” Many of our western cities began as military bases in the asymmetrical “war” against Native peoples. Vast indigenous cities once covered this land and much of their infrastructure has been completely eradicated. What Europeans viewed as a “untamed wilderness” when they first came to Turtle Island had once been a carefully maintained ecology with large meadows, grazing fields, roads, villages, and burial mounds, all dependent upon a regular Indigenous presence there that the genocide had destroyed.

The sacred artifacts and body parts that fill the Indigenous history sections of our museums were stolen by settlers as they tilled the earth and wrecked the soil for the next several generations of farmers, because they didn’t know to work with the “three sisters” of beans, squash, and corn. Now we have erosion, uncontrollable forest fires, and droughts on a land we still fail to appreciate because we have been trying to make it fit our English garden fantasies ever since we first set foot here.

And across the sea, European settlers in Palestine burn the olive trees.

If you cannot see the parallels between the United States settler-colonial project and what English invaders and Israeli settlers have done to Palestine, you are being willfully obtuse. In that, you would not be different from the average white American.

We have been taught to treat genocide as if it were an inevitable accident caused by bad Indigenous immune systems and an addiction to alcohol, rather than the conscious use of biological weapons and debt-enslavement peddled by white merchants. We create myths that make our modern day nation-state seem essential — for the “freedom” from religious persecution, for the “right” to bear arms, for the beauty of the wilderness that we helped to kill.

In telling these comforting stories, we try to convince ourselves that the American and Israeli projects are salvageable.

But we can choose an alternative. We can degrow our countries, slow our economies, withdraw our borders, and cede control of the land back to the peoples who know how to care for it. We can drop our rifles, learn new languages instead of forcing our tongues upon others, and pay what reparations we can afford. We can confront the fact that our ancestors became settlers because they were oppressed and displaced, and we can make a conscious choice to break the cycle of genocidal abuse.

If we were to abandon the settler-colonial nation state we would enjoy greater freedoms too — the freedom to move as we liked without government monitoring, the freedom to disobey orders that we do not believe in, and the freedom to invent new ways of socially organizing and living life. These are ancient freedoms that nearly every human society enjoyed in abundance, before the rise of settler nation-states.

Abandoning settler culture would allow for millennia-old ecological practices to be restored, healing our planet, and for humans to live in more communal, inter-generational ways. We could better preserve history, tending to some of the oldest burial cities, cities, churches, and mosques on the planet instead of developing over them, and learning from their timeless wisdom. We could enjoy a freedom so much greater than the one our colonist great-grandparents dreamed of, the kind that could only be paid for in blood with the barrel of a gun.

All we have to do is let go of our self-serving illusions about what America is, and what Israel is, stop defending the indefensible, and accept the humility of being just one people among thousands. To get free, we must release ourselves from the mandate of Manifest Destiny, and embrace peoples who have just as much right to exist on the earth as we do— and who know a great deal more than us about doing so well.

When I read An Indigenous People’s History, one of the things that really struck me was the re-periodization of history from an Indigenous perspective—the ways wars and battles and movement and daily life is framed and organized in a way that tells a coherent narrative about indigenous life, rather than centering settler experiences and stories and meanings—it was such a illuminating example of how a shift in perspective, a different lens, de-“normalizes” so much of what we take for granted.

I’m grateful to you for laying this all out in such a clear and compelling way. I’m very eager to think for myself and to hear from you more thoughts about the “how”—what this project of decolonizing that you nod to at the end of your essay looks like in the day-to-day, what it looks like in our kitchens and in our families and in our neighborhoods. I’m always seeking—almost as a religious quest—the “quotidian mysteries” at the somatic level that move us away from what you so accurately name as “sin.”

This is an awesome piece- and a timely companion for the book I'm reading at the moment, Kehinde Andrews's "The New Age of Empire", which charts all the strands of racial supremacism upon which the post-Enlightenment West is founded, and how they are all very much alive and well. Thanks Devon!