For the last eighteen years (the entirety of my adult life), I have never lived in a place longer than twenty-four months.

If you’re a renter, you know the deal: one apartment has leaks coming from the ceiling, thanks to a bathtub upstairs that the landlord never sealed up; in the next, you can hear skittering in the walls. I get a new job, so I have to head a mile south to find a commute that is tolerable. The relatively affordable one-bedroom on the corner where the ambulances are always blaring gets bought out, so the rent shoots from $900 to $1200 per month. Over and over the leaf blower of economic progress has expelled the flimsy debris of my life from the corners where it has settled.

There were less prosaic reasons for the many moves, too, like the 55-year-old roommate who would bang on my door at six in the morning accusing me of sampling her milk and let her dog shit on my rug. Or the boyfriend who stalked me after we broke up in graduate school, who would sit in the parking lot outside my window curled up into an angry, devastated ball, shrieking and crying until somebody came out the back exit and he could rush in to get me. I left the rug behind when I moved, because it had gotten stained. And when I escaped from the boyfriend, I left behind all the books from graduate school that reminded me of him, too.

As a renter (especially one with a limited income) you never have any control over your surroundings. Where you live, how much space you have, what pests reside there, what works in the building and what doesn’t, how things get fixed, if things get fixed — it’s all determined by market forces and landlord whims. Nothing is permanent, and everything is uncomfortable, so you learn to keep your life light and ready to be picked up and dashed away with at the first sign of trouble.

I never really learned to settle down into a place and let my weight expand gently all over it. It was better not to count on anything. Every time that I moved, I culled my possessions: the vintage exercise bike that I brought with me from Ohio got left behind when I darted from a depressing, windowless spot in Roger’s Park to a tiny studio in Lakeview. When the studio in Lakeview had cockroaches crawling up the bathtub drain, I found a dupe of a subletter and left behind my desk and half my kitchen items, and used a $40 folding table from Aldi as my counter, dining room table, and workstation for the next five years.

Because I had learned to orient my life around leanness and efficiency, I never developed the skill of attuning to my comfort. Did I prefer soft or bright lighting? Would plants filter the air? It didn’t matter. I didn’t have time for those things, or any money or space.

I insisted on only owning furniture that I could move myself, with my two hands. It wasn’t safe to be reliant upon anyone else — the man who hauls your bedframe up the stairs one night could be the person holding you down on it the next, and if you still need his help, you won’t be able to tell him that what he did was wrong.

For ages, my mattress was three thin layers of foam slapped together and held in place with a fitted sheet, and my “dresser” was a stack of milk crates. My body hurt, but I had no reason to expect it not to.

I was r/MaleSurvivingSpace personified.

People got sad when they saw me living this way. On visits back home, I would instinctively sit on the floor because I was used to having no chairs, and my mother would say it made her want to cry. When I had company over for a birthday party one year, all my guests sat atop the milk crates I normally kept my clothes in, and drank Stella Artois from peanut butter jars. I apologized and called myself a bachelor, kind of relishing the masculinity of self-denial, but they were all too grown-up and used to the creature comforts of wealthy families to find the act cute.

I wasn’t like them, the children of academics who had themselves become academics. My grandmother used to pick chairs and birdfeeders from the trash. On weekends, my dad would entertain us by driving around to garage sales and haggling with neighbors over a quarter. When each of them died, the family found their savings stashed in closets and under mattresses rather than in banks. Their generational traumas taught me to see the real value of money, which is to say, to be terrified of it: to part with one red cent was to bleed myself out in the dirt.

I grew into compulsive minimalism as a way for independent life as a disabled person to seem possible. There was always more I had to cut back on to settle up the competing bills of money and time. I grew to resent any cost I ever faced, all the apparent waste of groceries, bedding, window treatments, storage solutions, toiletries, medical bills, and repairs.

That’s one thing that people don’t talk about, when they complain about landlords: how much disregard for your surroundings that renting breeds in you. It’s not only that the owner of your building never cleans the pipes. It’s also that you have no reason to feel invested in the pipes’ long-term functioning, and every reason to feel bitter about the thousands of dollars you’re already wasting on a broken building each year.

And so you buy the Drain-o, even knowing it does damage. You don’t invest in a hair trap, because it shouldn’t be your job. Maybe you even flush kitty litter down the toilet, as one neighbor of mine did, because why the fuck shouldn’t you? It almost feels like revenge to wreck a place that was never yours, even though the only people who will suffer the consequences are the poor broke renters who come after you.

There is no gratitude, no sense of continuity — only a steady march of expenses and breakdowns that never stop, until you’re kicked back on the street again.

In her excellent reflection on class, gentrification, and homeownership, Having and Being Had, Eula Biss writes about seeing herself as nothing but her house’s temporary steward. The structure has existed for far longer than she’s been alive, and hosted a number of families; after Biss dies or moves, it will pass on to somebody else. She might exchange money for it, and have her name on the deed, but the house exists as part of something greater than her.

“The house isn’t mine,” Biss writes. “I don’t own it so much as a I take care of it…I have the sense that all of this — the brick the roses climb, the lath and plaster, the copper pipes, the oak floors, the coal room, the cracked slab on which it all rests — is a gift. Not to me, but to the future. The house is just passing through my hands. It’s a not a purchase, it’s a husbandry.”

Though she can never truly own the land or own the house, caring for it is Biss’ responsibility. And she wants to tend to it well, so the people who follow her can enjoy and have their needs met by it, too — and so that her entire neighborhood is not made worse by her (white, well-off) ownership.

When I first read the book in 2020, I was shocked to hear someone reflect on property in this way. I’d only ever heard houses discussed as a commodity to be traded, passed around, and broken down for the sake of fleeting profit.

At the time I was sheltering-in-place in a one-bedroom in Edgewater that felt imprisoning, and spending every moment that I could outside. There was dust in my corners, mildew on my ceilings, and I let my chinchilla Dump Truck chew up the baseboards. To regard a space with reverence and view it as a means of connecting to others across time was completely alien. I had never learned how to care.

But this June, after almost twenty years and fifteen moves across various apartments and sublets, I have finally arrived at a place where I might be able to stay a long time. I’m no longer paying a landlord’s bills with my wages. I have become, like Biss, the husband of a space. This home is my duty to protect, to build up into something that might last for me and everyone else who passes through it.

Suddenly I can see the consequences of my actions: A stick of incense left burning on the bathroom counter leaves three small, orange marks I have to buff out with a scrubbing sponge and a layer of Barkeeper’s Friend. When I ignore a leak from the hot water spigot that runs over the side of the tub, the liner swells up with moisture and has to be cut out and replaced. Life is no longer lived in pay periods, but in years. Unattended problems only get worse over time, and everything is riding on me.

At first, I tried coping with all this responsibility through my usual denial. But the people who loved me wouldn’t let me, because they were alive and had living animal needs.

Three guests stayed for the weekend, and the bathroom sink wouldn’t drain; I tried to snake it myself, but then water rained into the cabinets from the rusted P-trap I’d just busted. The plumbing company sent a red-faced, bellowing man named Wedge, who sweated puddles onto the bathmat as he examined the mess and told me that he was sorry, aw fucking shit, but he’d need to bust open a hole in my wall.

Then he brought out the sledgehammer and I went into quiet internal hysterics.

By the time Wedge started swearing again and apologizing because he’d missed the pipe and would need to open up the hole even larger, my mood had settled into acceptance. Sure, fine, I guess this is what I have to do. I want to have guests, and I want them to be able to brush their teeth.

Wedge dug around in the plaster and drywall for a while, cursing the contractor who’d put the wall up. It was probably the same person who’d redone the entire bathroom shoddily, not providing access to the hot water cartridge and never bothering to install any escutcheon plates.

I am learning what these terms mean — the bad cartridge is why my hot water pressure is so low, and the escutcheon plate is the metal disk that’s supposed to cover where the spigot meets the wall and block the water from getting in and rotting everything. In the course of addressing this one sink issue, I learn how to book a drywall contractor (and what drywall even is), how to match a paint color using a thin sample ripped off the wall, how to prime, and how to paint.

Then the shower stops draining and I learn how to address that too.

I’m learning how to clean, really clean, not just sweep up the major traffic areas and wipe down the spots of the kitchen table that have gone sticky. I keep bottles of white vinegar fucking everywhere, and use it to rinse off the insides of sinks and buff my bathroom mirror to a shine every time a drop of spit lands on it. I am buying magic erasers, giant trash bags, and loads of clear silicon caulk. I think to myself, if I ever need to buy someone a house-warming gift, it will be a lifetime supply of silicone caulk. You just never know when you’ll spring a leak and need more of the stuff.

I get a real kitchen table, the first of my life. My friend Shiloh sits at it and asks where my coasters are, and I tell her I have none. She rips a few paper towels from the roll sitting loose on the counter (of course, I have no napkins) and folds them into tidy squares.

“You’ll need to get some coasters,” she instructs me seriously, placing both our seltzer cans on the squares. “Otherwise you’ll ruin this nice wood.”

“Huh,” I say. And I run a quick mental simulation of the hundreds of glasses and cans that will sit on this table over the hopefully dozens of years that I might have it. I see myself growing older, meals being laid out and shared and the crumbs dusted away, the walls getting dingy with oil and needing to be washed, and all the other damages of time. I long for this space to remain welcoming forever, and realize that if it is to be, then I’ll have to make it so.

I walk into my bedroom and notice a widening crater on the edge of the old end table I have been using as a desk, where so many cups of iced coffee have worn away at the finish of the wood. There it is, the mark of blustering indifference. I don’t buy coasters, but I do keep using the paper towel squares. I buy a liter of Waterlox and seal up my untreated butcher block counters, then drizzle water on them and watch it bead, standing proudly with my hands on my hips.

I let people from out of town stay on the air mattress in the guest room. I have people over for cocktails and rounds of Fortnite. My friend Bridget comes and uses my projector to show me the game Bomb Rush Cyberfunk on Nintendo Switch, then we sit on my couch with my laptop and schedule her first HRT appointment together. When she hugs me, I realize she has been feeling something about all that we’re sharing — and I understand that hey, I am, too.

All my adult life I’ve considered the accumulation of items to be an unforgivable extravagance, and new responsibilities to be nothing but a source of dread. But gradually, I’m embracing the costs of being alive. The sheer complexity of a normal daily existence — all the little chores, the social visits, the bodily needs, the abundance of stuff — it had seemed to threaten to pull me down. Now it is revealing itself to be an anchor that can hold me, and others can gather around.

I want to have a life with real weight.

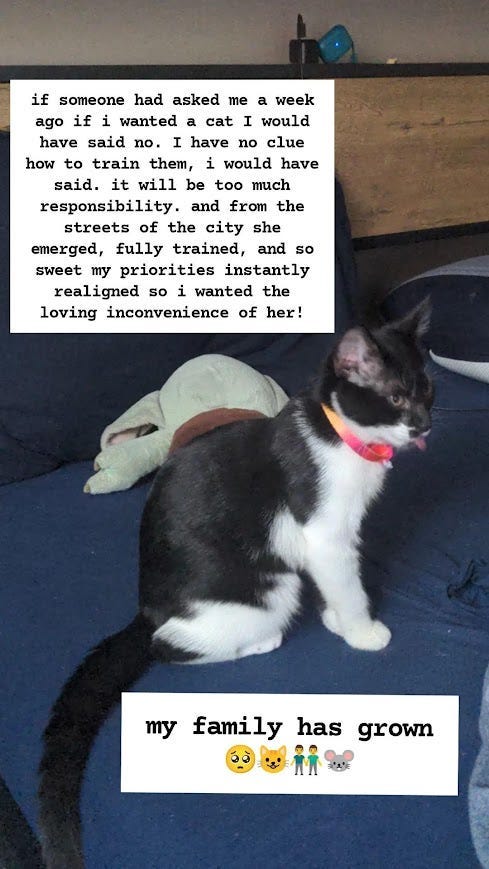

The final piece of this realization slid into place for me late on a Monday night at the end of October. I was walking with my partner to the deli to get a slice of cheesecake when we heard an insistent mewling sound. At first, I thought it was an alley cat in heat and was going to ignore it (our neighborhood hosts many feral cats, which a local volunteer group looks after and feeds), but some instinct moved me to stop. The crying sounded too desperate.

We followed the sound to find a small juvenile cat curled up on the back steps of a church. As we approached, she looked up at us pleadingly and shivered. I took the cat in my arms, surprised that she put up no resistance, and she crawled under my jacket and began to purr. She was bony, and cold, but remarkably clean. My partner bought wet food from the deli while I stood outside holding her, kissing her head. It’s okay, I told her. You’re safe now.

The kitten was loudly meowing the whole walk home, as we discussed what we should do with her. In my heart, the matter was already settled: I would keep her. I had never wanted a cat before, but I felt she was my child. The way she kept looking at me made anything but love and responsibility impossible.

It was a good thing she made such a ruckus to get our attention, I said. My partner deemed her Loquacious, or Loqi for short.

We got home and sat her on the floor, and she immediately began to roam and rub at our legs. My partner went off to get litter, which we poured into a thin plastic dish my sister had brought when she’d visited in the summer (along with Lysol wipes, a mug, and some cutting boards — all household items she knew I’d need, but would never have bought for myself).

Loqi knew how to use the litter right away. She stayed close to us all evening, leaving only to lap at her water dish and smack away at her food. Who would leave behind such a gentle, well-behaved cat, we wondered? She clearly hadn’t been living on the streets.

In the days that followed, we learned of the complications of cat ownership. A better-rested and well-fed Loqi took obsessive interest with my ten-year-old chinchilla, Dump Truck, and tried climbing up the bars of his cage while he kak-kakked at her and flung himself defensively at the bars. We locked her in the bathroom to consider her actions. Every time we left the house, she was kept behind doors, meowing for release but thankfully not taking frustration out on our curtains or towels.

The veterinarian told me she was unchipped, about five months old, and in fantastic health. She was given a round of shots, which cost me just shy of $400. In a month she’d need to be spayed, which would cost over $1000. The vet also gave me a small care package for new kittens, mostly paperwork on the various insurance plans I could buy and toxic foods to avoid, but it also included a tiny, cheap wool mouse that rattled. Loqi leapt after it instantly, then spent hours knocking it around the house.

I went to PetSmart and stocked up on catnip, crinkly toys, stuffed animals, wicker balls with bells in them, and a laser pointer, to the tune of about $65, but she didn’t care about any of it. All she wanted was the shitty Ali Express wool mouse.

I was gladly spending money on her, in a way I seldom had on anything or anyone. (The most Dump Truck had ever required from me was a $200 Ferret Nation cage, itself the top of the line for small mammals). It had me reconsidering the way that I’d grown up, and the way I’d constructed my own light, disposable life.

The way I was raised, wet cat food was something that only rich and intolerably finicky people bought for their cats. It was the mark of a person who’d never had to think practically or weigh hard choices. You didn’t regularly take your pet to the veterinarian or spend thousands of dollars on fancy surgeries for them either. You pretty much just waited until they were ailing, and then you helped them die.

We loved our pets, surely, but they were ultimately a possession, like a desktop computer or a truck, which was made to be used up and never built to last. We couldn’t really let ourselves get too invested in an animal’s wellbeing, because ultimately there were third shifts to clock in for, school to attend, lawns to mow, and a constant aching in our bodies that we had to ignore, too, so why would the dog’s arthritis merit treatment?

As an adult I’ve witnessed how my friends treat their pets and considered it almost lavish. Their homes are filled with all kinds of colorful and quirky pet-specific furniture, the food bowls overflowing with rice and fresh meat, and they spend more on life-extending veterinary surgeries than I’ve ever invested in my own health, even when I was physically disabled. I never imagined that I might live in remotely the same way.

But having a cat now, and loving it, and wanting it to be healthy, I recognize that I was raised in conditions of kind of covert neglect. I’ve never known how to properly love on an animal because I didn’t know how it felt to receive such love myself.

My family had quite legitimate, material reasons for doing as little as they did, in some areas, all while continuing to protect and feed me. They were brow-beaten, exhausted, and depressed, and my sister was in and out of hospitals with problems far more serious than mine. Everybody was disabled and no one was really holding it together. And so, as a result, I never learned how to cook, or to clean, or pursue hobbies, make friends, or care about things — nobody taught me. But I did master the art of surviving on as little as possible, and keeping my mind occupied and far away from the troublesome emotions of my body.

Until I moved into my home, and got Loqi, I still viewed every fresh responsibility in my life as a threat. Dump Truck was the perfect pet because he demanded so little; my job was the perfect job because I didn’t believe in it, and I could half-ass it from home without the waste of a commute or much face time with other people. If I played things cannily, I could spend multiple days in a row solely on writing, which brought me a sense of professional worthiness and earned me money, and only stop when the protein bar wrappers and coffee cups piled up too much or I ran out of underwear.

Even then, though, I’d feel spite toward anything that made me stop. Every head cold or leaky radiator was a personal attack.

But with this cat, this fucking adorable cat, I am flooded with such deep parental feelings that I am a man transformed.

I used to hate clutter. But now my floor is covered in rattly little toys I keep hoping to convince Loqi to play with, swatches of fabric with interesting textures, and opened La Croix containers that she likes to jump through.

I used to hate chores. Now I kneel before the litter box four or five times per day, sifting her waste from the silica and depositing it into thin plastic bags, and when I do the dishes, she sits next to me and watches, and I sing.

I have always been a fierce defender of my sleep, but now I let five fired-up pounds of predator-in-training dash around my room attacking my feet (and sometimes even my eyeballs) before settling down beside me to sleep, and somehow, it’s the most peaceful rest that I’ve had in years.

I step away from working on a draft even when the writing is going well, now, just so I can snuggle with her. I never did things like that before. I stare into her eyes, and rub at her cheeks, feeling the little waterbed pump of her purring switch on. It fills me with the luxurious sadness of love.

I remember that when I first got Dump Truck in 2015, I cried at the thought of him dying every single day. I’d let him out of the cage to play for hours and just watch his tiny body flopping around and could think only of how temporary his youth would be. Chinchillas live a long time by the standards of most pets (upwards of twenty years is not only possible, but common), but I was still horrified that he couldn’t outlive me.

All the love and care that I poured into Dump Truck, it seemed, would one day just go nowhere. It was for nothing. Whatever need I’d allowed myself to feel for him would be suddenly and forever unmet, and I would be weaker for having ever known it. I adored him, but I still thought of him the way my family had been indoctrinated to view their pets, or their children: as a thing made only to satisfy others, rendered more valuable the longer you got satisfaction from it and the less it took away from you.

I try not to think of living beings like that anymore; my politics have evolved beyond that. I don’t want to measure a life’s worthiness; I don’t want this tired old fixation with how impressive, put-together, or self-denying I look, or to hate every lovely moment that gets in the way.

With baby Loqi, this move away from capitalistic drive and classist posturing finally feels natural. I take great pride in watching her grow into a heavier, hungrier animal, knowing it’s happening because she’s nourished and safe with me. But mostly, I just want her to stick around and be happy for however long we both can reside in these moments together. I want Dump Truck to be able to feel protected and adored in my company, too.

And I want to snatch up all of those moments with my babies that I can, my Outlook calendar and bank account be damned. For once my mind not is flitting about some abstract realm of obligations and guilt. It’s present in the filling of the foodbowl, the placing of a fecal sample in a tube for the vet. Nothing is real but this.

For a very long time, I kept all my emotions buried under mountains of work. Nothing good lasted, and nothing in my reality was under my control, and so it felt protective to never be present in my actual life. By keeping my mind always whirring around some task or problem, I could avoid feeling the sorrow that hung under every positive moment. If nothing ever felt precious to me, then I wouldn’t have to mourn its loss.

An Autistic Considers Impermanence

A partner and I have seen each other for going on three years. At the outset of the relationship, our sexual connection was the strongest I’d ever known. We’d fuck five or seven times in a single day back then, pulling one another away from the kitchen stove or a work …

But I know how much love is within me because I am sad all the time. I’ve beaten myself up so badly trying to shut both feelings out — the ardor and the longing, which can only exist in tandem. One week passes, and my cat hits a growth spurt, so her eyes are no longer too big for their sockets. She looks less goofy, and more normal. More like an adult cat. Time is pulling us forward. Just yesterday Dump Truck was a juvenile who didn’t know how to drink from his water bottle. Now he sleeps on his side, looking deflated, and it frightens me.

There is so much to lose — that is, so much to hold dear. And so many discoveries to make if I only remain present. It is a delight to watch Loqi pause at the foot of Dump Truck’s cage, remembering she is not supposed to bother him, and instead grabbing a toy. It thrills me and rends my heart to see her learning, the same way it did when Dump Truck first learned he liked the opening theme to Twin Peaks. With every loss, with every change, we are finding ways to be alive with one another.

I will take on the inconvenience, the extra duties, the distractions, and the loss. I will vacuum up the hair and the dry chinchilla turds. I will watch their bodies schlumping over cutely as they kick and fend for my attention. I will wake up to the sounds of them dashing and rattling the floorboards. I’ll take the scuffs on the walls, the costly repairs, the lines from smiling on my face and I will be better for it.

Let life be harder, messier, and so stuffed full of meaning that it almost bursts from its weight. I want to be right here. I want to care.

I really identified with this piece, Devon! I've struggled with this for the better part of 6 years since moving into my own home. Loqi is the cutest little kitty! :) Welcome to Cat Parenting! My boys have been with me for nearly 10 years now, and the joy they have brought me in that time is incalculable. Cheers to you for doing the hard work of sorting and working through the financial trauma inadvertently bestowed upon you by your family. It isn't easy, but it is worth it. YOU are worth the freedom from these outdated views, which yes, kept you safe in a capitalist hellscape, but no longer serve you. It's ok, even encouraged, to have nice things. :)

I cried through so much of this. So glad you found your place and your people, at least for now and maybe for a long time. It tells me maybe there could be something like this for me to love eventually, too.