Abolish Age

Every person deserves both freedom and support -- no matter how long they’ve been alive.

I’ve been writing about youth liberation a lot recently, particularly in this piece encouraging queer people to interact generously and patiently with the minors they encounter on the internet, and this one arguing that we should all treat sex as a neutral fact of life that kids are not hurt by learning about.

This line of thinking draws a lot of questions from people. The idea that children are fundamentally different & separate from all other human beings is a cornerstone of how our educational and legal systems work, and the concept of legal “minority” does a lot of heavy-lifting in helping us figure out questions of consent, abuse, and collective responsibility involving kids.

If every child is completely incapable of directing their own life, then moral questions about how to treat them seem easy: give them a guardian with almost unlimited power to make decisions and protect them from themselves, until they get old enough to handle themselves. Usually, it’s assumed that the proper guardian for a kid is their parents. And typically, it’s assumed that a person is finally old enough to direct their own life when they become 18 (though increasingly, many people point to really badly done brain-science to argue that the age of majority should be 25).

The reality is a lot more complicated. Many parents do not have their kids’ best interests at heart, or just don’t have the skills and knowledge to provide what their queer, disabled, or otherwise non-conforming kid needs. Some children know from a very young age that the religion being forced on them by their family is not right for them, or are obviously hurt by their parents’ attitudes about food, body size, physical punishment, or any number of personal values.

Most kids do need a ton of guidance in navigating the world, but they also have unique insight into what they need and what matters most to them that no adult’s judgement can replace. And as many child abuse survivors know, the wrong kind of “protection” can be just as bad as having no protection at all. Many disabled people would further point out that the need for support does not necessarily end when a person turns 18, and needing support does not necessarily make a person incompetent.

So is there a better way to think about how our society distributes both support and freedom, other than numerical age?

I think there just might be.

I understand that this is an uncomfortable topic. Questioning the legal minority status of children freaks a lot of people out — and understandably so! It sounds like an argument for child labor, or for permitting adults and children to have sex.

And that is because in most of the world, the need for support and the lack of freedom are assumed to be linked: it is assumed that if a person cannot do things on their own, then they also should not be trusted to make decisions for themselves, and vice-versa, that if a person wants freedom, they must earn it by becoming independent — never relying upon government benefits or asking anybody else to do complicated and difficult things for them.

I’d suggest we call this kind of thinking the Support-Freedom Dichotomy. And I think believing in it screws up a lot of our conversations about children’s rights, disability justice, and protecting the vulnerable from abuse more broadly.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Instead, we can have a more fluid and nuanced discussion about what society owes to all people — at all ages — and stop assuming that if a person needs support then they can’t possibly be trusted to manage their life.

Let’s explore.

I got this great question from Tumblr user ashleythetraveler on the day that my Interact with Minors piece went live, asking what should replace our current legal paradigm of treating all children (and all legally categorized as “childlike,” like intellectually disabled folks and senile elders) as if they are non-humans who do not deserve freedom.

I think we all know on some level that age is a pretty blunt instrument for measuring maturity and capability. We all develop at different rates and in different ways, especially when you take into account environmental factors as well as disability. I said my first words at six months old and didn’t get comfortable walking until I was two. Both of those are developmentally ‘abnormal,’ but in completely opposite directions. Intellectually, I was able to spar with most adults before I was old enough to drive a car, but at age 36 I still cannot handle cooking dinner or doing my taxes. (I also really shouldn’t be trusted behind the wheel of an automobile, if I’m being real).

Research suggests that many Autistic people develop social and emotional skills at a slower pace than most non-Autistics; in our 40s, 50s, and beyond we are still learning a lot of valuable lessons about how to better relate to people, and show less difficulty in our relationships as time goes on. I didn’t learn how to make friends or name my emotions until my 30s — was I not an adult until then? What skills must a person have to qualify as really, fully an adult?

This points to a major problem in how our current systems look at intellectually disabled people — their abilities and needs are often summarized using the confusing metaphor of “mental age.” A person with Down Syndrome who cannot read or use the toilet might be labelled as “mentally three-years-old,” for instance — but what does it mean to be mentally three? Which kind of imagined three-year-old is setting that standard? Which skills are important to determine someone’s mental “age”? If a person can write fluently using an adaptive communication device but can’t tell when they need a shower, what mental age do we give them — and which rights?

Why does ability level determine the rights that a person has, anyway?

And what about the role of life experience, which brings with it so much wisdom? My friend Arin’s sister is mentally two years-old according to her doctors, but she’s spent thirty years getting to know her family and has a profound understanding of what pushes their buttons. When she wants Arin to leave the room, she plays Mukbang videos on her tablet and smiles at him mischievously, because she has learned he hates the sound of chewing. She has strong preferences about how she wants to be treated, and is intentional and insightful in expressing that. Does this make her no longer a “child”? And more to the point, why do we assume that to be childlike is to lack preferences or the ability to express them?

Despite all the loud hand-wringing about problematic age gaps that happen on the internet, the fact is that people can be in any number of life stages no matter their age. A 22-year-old, single line cook may have a lot more in common with his divorced 42-year-old co-worker than his married, home-owning cousin who is about his age.

If you’ve ever stayed in a mental health clinic or addiction center you’ve rubbed shoulders with people putting their lives back together at any number of ages — ability is fluid, and so is need, and a lot of what we can and can’t do is rooted in the resources we have available at the moment. I know a lot that my Zoomer buddies do not, but some of them are vastly more emotionally even-keeled than me, just like I have more emotional skills than my parents who grew up in a less psychologically enlightened era. The number of years that a person has spent on the planet doesn’t tell you much at all about what they are capable of. Development just isn’t linear.

The problems with using age as a benchmark become even more clear when we consider the many complicated realities of aging. A person in the early stages of Alzheimer's can make decisions about how they want the remaining years of their life to go — where they want to live, who should look after them, whether they should be taken off life support, and where their money should go just to name a few. But the person that they become over time may have other feelings. At what level of ability does someone’s preferences stop mattering?

As we age, we all gain experience and lose skills. To whatever extent that growing older does make a person more powerful, at some point the process does reverse. So is there an age at which a person should be banned from being able to drive, to own property, to run for President, or to vote? Or should we make such decisions based on intellect? This logic heads to eugenicist places pretty quickly. You can’t really define what an adult is or should be without drawing an arbitrary line in the sand over some level of ability, and dehumanizing anyone on the ‘wrong’ side of it.

But what if we didn’t take anybody’s agency away, regardless of ability level or need?

In our current society, people considered “children” receive certain resources that nobody else gets, like free schooling and special state-provided health insurance, and if they do not have a guardian they are assigned one. A legal adult gets to make all legal, medical, and educational decisions for the child, and makes sure they remain housed and fed.

There are many adults who could use this kind of support. But relying upon others for such support means you don’t get the rights of a legal adult, according to the Support-Freedom Dichotomy. If an intellectually disabled person can’t understand complicated legal and financial documents, for instance, they’re likely to be placed under a conservatorship and lose the freedom to buy the things they like or live how they want to live. They do have preferences and insight into their own lives, but because they need help carrying those preferences out, they don’t get to make them.

I propose that rather than equating needing support with losing freedom, and instead of trying to define a simple category of people who does not get to be an “adult,” we ask specific questions about people’s needs, capabilities, preferences, and desires in a way that allows for everyone to get both the help and the autonomy they require.

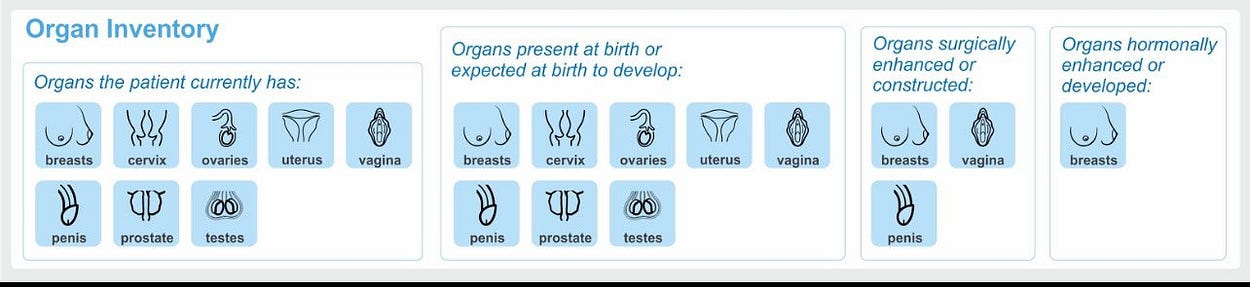

In medicine, gender is a blunt measure in much the same way that age is — most doctors’ offices only ask your gender, and make a ton of assumptions about which organs you have and what your hormones must look like based solely on that. This doesn’t just fail transgender people, it also makes medical care worse for cis women who have had hysterectomies, cis men who have had mastectomies, intersex people whose bodies don’t match up with either “male” or “female” expectations, and lots of others.

But there is a more specific and nuanced alternative that many healthcare advocates have pushed for, and that a growing number of medical facilities use: the organ inventory.

Instead of assuming that every “female” person has a cervix, uterus, breasts, ovaries, and a vagina without bothering to ask about it, the organ inventory asks for the patient to report exactly what anatomy they currently have. This allows for more specialized, targeted medical care that reflects the actual needs of the patient and their body.

I believe that we could take a similar approach to questions of autonomy, support, and age. Rather than assuming that all people over the age of 18 possess the exact same abilities and do not require the assistance that “children” need, we could take a specific inventory of needs and preferences, asking questions like these:

What kinds of financial support does the person need? Do they need food stamps, housing, education, healthcare, help paying for childcare? A person can be incapable of paying their bills no matter their age. These resources should be distributed based on need, not be cut off when a person turns 18.

What daily life activities do they need help with? This might include things like housekeeping, cooking, grocery shopping, paying bills, bathing, transportation, or taking medication. Being unable to bathe oneself does not make a person a “child,” and some young people might need help with a few practical life challenges but be otherwise capable of living on their own.

Where do they need help making decisions? Would the person benefit from a professional mentor, a legal advisor, a financial advisor, or a medical advocate? Lots of otherwise mature “adults” struggle to understand complicated legal documents or make sense of their 401k. Imagine if we assigned a supportive advisor to every person who wanted it, so that they could make their own choices with clarity and empowerment. In such a world, children and intellectually disabled people would also have a lot more control over their lives, while still being protected against scams and abuse.

What are their priorities? Even if a person cannot speak or make certain complex decisions on their own, they still have strong feelings about what they like and do not like, and their actions communicate a lot about their preferences. What makes them happy? What sensations do they enjoy? Which ones do they hate? What makes them move away or show distress? A person with advanced Alzheimer’s probably does not care what their investment portfolio looks like, but they should still get to make decisions about what they do each day, and a supportive advocate can help them get access to the records they like to listen to, the DVDs they like to watch, the snacks they enjoy, or the dolls they like to cuddle with.

Where do they need someone to advocate for them? If a person is unable to put together words or advocate for themselves, how might an advocate push for them to experience more of what they enjoy in life, and minimize their frustration and distress? For example, if an Autistic twenty-year-old loves video games, how might an advocate work to help get them more of the games that they want, and the time alone to enjoy them? Similarly, if a child is being mistreated by a relative or a teacher, an advocate might push for their needs to be respected — or help them change living or schooling situations if that doesn’t work out.

What gets in the way of their freedom? This could include things like a lack curb cuts and elevators around the home of a wheelchair user, a manipulative or exploitative family member in the home of a child, a lack of education about sexual health for an intellectually disabled person, paternalistic attitudes about the freedom a young woman should have over her body, a lack of transportation options in a lonely queer kid’s town, and so much more. If we focused on removing the barriers to freedom, we could empower many children, elders, and disabled folks to do much more of what they like with their lives. See this article from Emma Barnes on the ways in which a person’s environment disables them.

“Your Expectations Are Disabling”

It’s exhausting to seek accommodations. Here’s how to make it smoother.eggybing.medium.com

What do they have to offer? Every person has skills and knowledge they can impart to the world, and generally most people want to feel as capable as they can. Does the person enjoy pet-sitting, cleaning, making art, emotionally supporting others, body-doubling, watering plants, sorting socks, singing, or telling their story? Who in their community has needs that are not being met. If we really appreciate the disabled and the young as full people, we can allow them to give back to others on their own terms.

How might they participate more deeply in their society? Every person should have the right to participate in political discussions, express criticisms of their society, advocate for change, and suggest ideas — including children, disabled people, and elders. How can we reorganize our political process to ensure they are heard? In what ways does our current political system make it impossible for them to speak up? A move toward more community-driven, participatory politics makes it easier for everyone to contribute.

What makes them vulnerable? Are they affected by racism, sexism, poverty, transphobia, disability, an abuse history, or xenophobia? Can they read or speak the language used most commonly in their country? Do they have any money? Any social connections? Power is a complicated thing, and age does not always make a person more privileged. Vulnerable people deserve protection regardless of whether that vulnerability comes from being a “minor” or being minoritized in some other way.

What do they need to make their relationships more equitable? A stark age gap is just one of the ways in which power can become imbalanced in a relationship. Rather than trying to ban all relationships in which there is any power difference (which usually just makes the less powerful partner even more isolated), we could work to reduce the impact of that difference. If one partner depends on another financially, they’re at a disadvantage regardless of age , for example — but if they were given a financial safety net, they would always have the freedom to leave. If a child has multiple supportive adults to turn to aside from their parents, they’re less subject to familial abuse as well.

I am an abolitionist and anarchist at heart, which means I do not trust the state to decide what is right. I do not believe that our laws are inherently moral, or that states set policies with the intention of helping most people. This forces me to confront the fact that 18 is not in fact a magic age at which a person suddenly becomes both deserving of freedom and no longer worthy of social protection.

No age absolves us of our shared responsibility to look after a person’s life and honor their autonomy — whether they’re 13, or 8, or 54, or 25. Control over one’s body, authority over one’s destiny, the ability to have a say in how one’s community is run and to actually be listened to some of the time, the ability to access food and shelter, and the freedom to choose and follow one’s own religious practices — these are all things that ought to belong to all people of all ages. And these are things that unjust systems of power (including the state, the education system, or a controlling and isolating family) currently have the ability to take away from people of all ages.

When we acknowledge this, conversations about how power can be leveraged against the young, the old, the disabled, and the otherwise vulnerable all get a lot more complex. Conversations about consent, religious freedom, political representation, access to education, body autonomy, and the like all get way more dynamic too. Child liberation forces us to acknowledge that we are all coerced, exploited, and oppressed in our current system in various ways. And so, we all have a stake in setting children free.

Even if it’s uncomfortable. Even if it forces us to question almost every assumption our society has been built upon. We can look at one another differently, and stop dehumanizing those who are young or otherwise in need of additional help.

And just maybe, we can abolish age as a meaningful way of categorizing people.

Really value your writing and research Devon, thank you.

For those that are interested in this subject Sophie Lewis has an upcoming book about Child Liberation and Madeline Lane-McKinley also has an upcoming book/essay titled Solidarity with Children - https://www.haymarketbooks.org/books/2610-solidarity-with-children

This interview between Madeline and 15 year old MK Zariel is also excellent - https://thechildanditsenemies.noblogs.org/post/2024/08/08/madeline-lane-mckinley-and-childhood-as-a-concept/

This is an important conversation, I really appreciate your embrace of nuance in this article.

Cognitive development and wisdom are two related ideas that we've arbitrarily added specific ages to (understandably, because the law is written on paper, but arbitrary anything has issues).

Developmentally, there are a lot of really good reasons we don't teach calculus to tweens, but that doesn't mean we ban discussions of math. It would, in fact, but stupid and counterproductive to do so.

Wisdom is more elusive, but perhaps more relevant: what we do with information based on experience and - often - the patience to know when to act and react (or not) and avoid overreacting.

Kids are rarely wise, but you've rightly pointed out that we've overreacted as a society: We're protecting kids from the information that would actually protect them.