Interact with Minors

Against the collective neglect of the young.

When I was in fourth grade, I made an America Online account. The handle I chose for myself was Batlover4, because I wanted to be a bat biologist when I grew up, and I was in the fourth grade.

I started frequenting AOL’s game review community, the Antagonist Game Network (or ANT for short). Every day after school I would spend an hour or two in the ANT chat rooms and posting on their weekly forum threads. I interacted regularly with dozens of people — some of them children, but most of them adults.

There was a weekly caption contest on ANT — a moderator named ANTPogo would post a screenshot from the likes of Banjo Kazooie or Tomb Raider III at the top of the week, and members would compete to write the funniest response. ANTPogo was a game reviewer in his mid-20s with a snarky voice and a CGI wolf’s head for an avatar, whose audio commentaries on games industry news I quite liked. I decided that rather than submit captions, I would start role-playing as ANTPogo’s adoring stalker, sending him unhinged love declarations and cartoonishly violent threats into the caption submission box.

Thankfully, ANTPogo and the broader gaming community found my antics funny. It was 1998 and I was writing in the prototypical rawr random register that would soon become inescapable among tweens and teens.

With my claims of having studied all of ANTPogo’s favorite anime waifus so that I could imitate them, and my promises to kill all his enemies with knives and hammers, it must have been clear I was just an embarrassing kid. Yet everybody humored me and played along with my character. ANT Pogo began publishing my captions every single week in a special sub-section of the site called Batlover4’s Asylum.

I became a fixture of the site. When ANTPogo mentioned he was moving house, complete strangers messaged me on AIM to jokingly ask if I had found his new residence. A competing “stalker” introduced herself and we began a fake rivalry, and ANTPogo pretended to be terrified of us. An entire ANTPogo-stalker storytelling universe emerged with numerous characters and plotlines that unfolded on the caption contest page over the course of years.

In all the time that I spent on ANT, not one single adult was ever inappropriate with me. Though I myself was pushing boundaries and pretending to desire a grown man, nobody ever broached sexual topics with me or asked me for any private information. My comedic writing was treated as something interesting and worthy of engaging with, my awkward moments looked past with grace.

Being on ANT gave the 10-year-old me confidence in my ability to improvise, write jokes, and interact with a diverse network of people in drastically different stages of life. I left the community a few years later a more mature, capable version of myself, and a better writer — all thanks to the care of adults whom I’ll never know the real names of.

After ANT Games, I joined an online forum called Invader Zim Obsessives Anonymous (or IZOA). By then I was a morbid 13-year-old who loved gore websites and wore a pin with the word PSYCHO spelled out in flaming letters on my jean jacket.

I didn’t have many friends at school, but on IZOA I was well-connected. I role-played a female version of Invader Zim’s robotic companion GIR, Girgirl, who had a small metal daisy jutting out of her head. Other users drew fanart of Girgirl for me and we put together sprite comics. But I was most famous on the forum for my weekly rap threads, where every week I’d write a verse summarizing the latest episode of the TV show and name-dropping my IZOA friends.

I became close with a few other teens on the site, including a Black 17-year-old kid with acne scars and a bright bucket cap who used the handle DemonOni404. We shared all kinds of secret and taboo thoughts with one another.

DemonOni404 told me that he’d been sent to an institution once for cutting himself, and that he sometimes dreamed of killing his abusive brother. But ever since finding the forum, he said, he was feeling a lot better. When I went on vacation with my family, I warned DemonOni404 that I would be away from my computer for a week, and I spent all that time wondering how he was doing. One evening, he messaged me begging to know how it was that vaginas got wet. I told him that I didn’t know. Honestly, I’d had no idea vaginas even got wet until that moment.

DemonOni404 and I cared greatly about one another, though we could only convey it by trading links to jump scare videos and talking about fictional violence and sex.

The creator and moderator of IZOA was a woman in her mid-twenties who I’ll call Ana. We all looked to her as a big-sister figure. Whenever a role-play that we were writing featured alcohol or drugs, we would ask Ana what taking those substances was actually like, and she’d answer with frankness and appropriate remove.

“Tequila is my favorite but that’s what makes it dangerous,” she’d say. “Being drunk on tequila feels like racing down the highway listening to the song Alcohol by Barenaked Ladies. I do not recommend drinking and driving ever, by the way. Not even for one block. I have lost friends to DUIs.”

On the IZOA forums, I had a team of creative collaborators and an appreciative audience who looked forward to my raps and comics. I found people with whom I could satisfy my curiosities about sex, drugs, and death, and adults who could mentor me without being paternalistic or demanding. When DemonOni404 had mental health episodes or his behavior became erratic, I knew that I could have asked Ana for help, but I never felt that I had to. I trusted the little community that I was a part of, and that made me highly tolerant of discomfort, and resilient.

I would join many other digital communities while I was still a minor, including the Asexuality.org forums and a politics & culture blog called Dangerous Intersection, on which I wrote regular essays.

Adults on these sites nourished my intellect, praised my writing, recommended books and documentaries to me, and sometimes even chatted with me on the phone when I was horrified at early-2000’s militarism and homophobia. I walked away from these encounters with adults feeling like a person with agency and a voice worth listening to. Yet again, nobody violated my boundaries.

When I was 16, I had a Myspace where I posted random short essays and selfies. A local “photographer” in his late 20’s messaged me complimenting my appearance, and asked if I wanted to do a photoshoot in his basement studio.

I was in the throes of an eating disorder and insecure about my body, so I found it alluring to hear I had the makings of a model. But something felt off. The way the man addressed me was completely unlike every online interaction I’d had with adults online. He was leering and impatient. When I expressed doubts about showing up to his apartment in the middle of the school day all alone, he mocked me. He couldn’t stop talking about how good I looked.

I ended up bailing on our plans at the last minute, certain that I’d spared myself some great trauma. In my life on the internet, support and respect from adults has always been abundant, and so I recognized their absence.

I worry that today’s generation of kids on the internet have never gotten to develop much digital agency or form safe, empowering relationships with older people. More broadly, I think our current culture of isolating children from all unrelated adults, supposedly in the name of their “protection” only causes them to become more ignorant, lonesome, and vulnerable to exploitation.

Some readers might find it shocking that I look back on the era of harlequin fetus screamers and Newgrounds.com porn games with such fondness. And certainly, I understand that many people of my generation didn’t have such positive experiences interacting with adults online.

But my peers also faced predation from the adult bosses at their jobs, or from their uncles, or the trusted women at their church. It was not a desire to expand their horizons that led any of the teenagers I grew up with to be abused, nor was it an interest in sex (thought many of them curious). It was their lack of choices, and their desperation to be seen as worthy by one of the few adults in their social circles that most often led to that.

As I have written before, abuse is caused by dramatic differences in power, not by the mere existence of taboo “adult” content involving violence or sex. The mere existence of sexual knowledge (or adult themes!) is not dangerous. It is, after all, children who lack knowledge about sex who have the hardest time recognizing abuse and seeking help. Child sexual abusers tend to target victims who are lonesome and do not have present and supportive caregivers or close friends, because they know that those children will not recognize the difference between safe and unsafe attention, and often have nowhere else to turn if they want to feel heard.

Your Fear is Dangerous & Your Power Is Greater Than You Think

This piece was originally published to Medium on September 17, 2021. Why I’m migrating my archive to Substack.

There are many ways in which restricting youth access to information technology and training adults to avoid all contact with children makes kids even more powerless and dependent.

If a child cannot post their sexual health questions on Ask Alice or go searching around online, then they have to believe whatever they hear from their parent or priest. If a young person longs to taste the freedoms of adulthood but aren’t given any room to explore, then the grown-up in their DMs telling them that they are so mature becomes a hell of a lot more seductive.

And if a kid never gets to search for sexual content online, learn about adult sexual experiences, or touch themselves and find pleasure in the privacy of their own minds, they may never fully learn that their body is them, for them to enjoy and express themselves however they see fit.

For queer youth, the dangers of isolation are amplified. A study published in the journal Child Protection and Practice in April of last year found that LGBTQI+ children face an elevated risk of grooming and sexual abuse because they are discriminated against by peers, preached against within their religious communities, and mistreated or kicked out of the house by their families — and also, because an adult with no respect for boundaries might be the only person offering to talk with them about queerness or sex.

It’s very difficult to know the difference between a healthy relationship and exploitation when a predatory adult is the first queer person a kid ever knows. If a relationship with an abuser is the only way that a teen ever gets to live out their queerness or explore their budding sexuality, then it becomes immensely difficult for them to walk away — leaving the groomer is like tearing off a crucial part of themselves that never gets expressed otherwise, or even seen.

This is also true of children who have the early rumblings of kinky sexualities, too — when you long to be controlled or tied up, you need a safe outlet to learn and fantasize about doing such things consensually one day. If you do not know that such options exist, you’ll settle instead for abuse. The more options that a child has to learn about sexual practices, to meet other queer people of all ages, and to form appropriate relationships with unrelated adults, the harder they become to manipulate, and the more power they have to walk away.

Throughout my adolescence I used the internet to grapple with my budding sexuality. Role-playing as a robot girl let me express my detachment from human womanhood, and explore the realm of kink; a bit later, on the Asexuality forums, I spoke to numerous adults who had realized that sex and monogamous partnership weren’t for them. Their stories soothed my anxiety that I didn’t have a future.

In my adolescence I suspected I was something other than a cisgender woman, and I tested this by trawling through endless reams of straight porn and noticing that absolutely none of it moved me. Then I found websites devoted to my fetish and was struck with an all-body bliss, and the massive relief that I wasn’t completely alone.

I wasn’t disturbed by anything that I found; I was educated by it, and let loose upon a world beyond my quiet suburb.

If I hadn’t gotten to know about alternate models of sex and relationships thanks to lots of weird, freaky adult content on the internet, I might have settled into an airless, unfulfilling straight partnership with some random boy in my class, whose pushiness and misogyny at least made me feel controlled in the ways I fantasized about at least some of the time. I would have sleepwalked through all the expected stages of a typical straight relationship, and found myself trapped within a marriage in a small town where nobody else was trans and kinky like me.

Or I might have just continued starving myself into an androgynous shape and a waking trance, as I was often trying to do in those days, because my body and reality felt like prisons.

I certainly wouldn’t have been better off using the social media of today, awash as it is in insecurity-breeding imagery and moralistic censorship of everything to do with sex and queer identities. I wouldn’t have been able to find the information or community that I needed with any ease. I might never have become a writer. Hell, I might have projected my desire for solitude and erotic control into becoming somebody’s tradwife.

Though the internet began as a scarcely-regulated wilderness in which all manner of material could be published and children could be harassed and traumatized without recourse, children are emphatically not protected when we transform the online world into a sanitized, advertiser-friendly amusement park in which users never step outside of their own tiny social bubbles and nothing that might offend or shock anyone can ever be said.

When we segregate children from the rest of the world and censor all the information that they access, we suffocate the many people they could one day become — and show that we do not care at all for the fully-fledged, complex humans that they are right now.

On many social media sites, it has become de rigeur for users to demand that every person on their follow list disclose their exact age, block all people under the age of 18 on sight, and cover their profiles in statements demanding that MINORS DO NOT INTERACT with them in any way.

On sites like Tumblr, X, Bluesky, and TikTok, it’s typical for minors to be included within a long list of undesirable followers in a user’s bio, alongside TERFs, pro-shippers, Zionists, racists, or men.

(That a group that possesses essentially no freedom or legal personhood in society is placed right alongside members of hate movements and oppressors and considered unwelcome in the exact same way doesn’t seem to make anyone bat an eye. It’s also quite typical to hear people declaring that they hate minors or children in such statements.)

In the current cultural and legal moment, including a “Minors DNI” warning in your bio is understandable even if it does nothing to prevent kids from browsing your page. There is a great deal of social pressure to avoid even the appearance of inappropriate boundaries with children and, for queer social media users in particular, often a genuinely felt need to protect oneself against bad-faith allegations of abuse.

Trans feminine social media users especially run the risk of being “pedo-jacketed” by their critics (read: accused of engaging in predatory behavior toward children for having a blog that contains any mature content of any kind, or even for simply for existing in the public sphere as themselves, because their very identities are seen as inherently sexual, and sex is seen as inherently dangerous).

In the last several years, social media sites have cracked down heavily on sexual content, often using content moderation algorithms and AI filters that cannot tell the difference between porn, artistic nudes, suggestive imagery, beige couches, and otherwise completely safe-for-work LGBTQ content.

This has further muddied the cultural waters regarding what is appropriate or inappropriate for kids to see. Now the average YouTube creator thinks it’s normal to never say the words “sex” or “rape” aloud in front of a general audience, for instance, no matter how neutral or factual the use of the words might be, and any mention of queer identities has been advertiser-unfriendly (and therefore, child-unfriendly).

Laws like FOSTA and SESTA drove sexual content creators off sites like Tumblr and Reddit, and led to the mass deletion of decades’ of artistic material. Confusion over policies like 47 U.S. Code § 230 have also caused many people to mistakenly believe that if a person under the age of 18 views mature content they have posted, they personally could get in legal trouble (though this is generally not the case).

Most social media companies do place age restrictions on who can make accounts, usually requiring users be either older than 13 or 18. However, most of them do not require users submit proof of their age or any form of legal ID. (And given all the abuses of user data that companies like Meta and X have committed, I would consider this a very good thing).

But for the average socially-conscious social media user, this creates a tremendous source of anxiety: there is no way to know that every person scrolling through your blog, TikTok, or Instagram account is over the age of legal majority. In fact, you can be almost assured that they aren’t. So what happens if you talk about sex, violence, or self-harm on your pages? What are you supposed to do?

In this landscape, the words “Minors DNI” act as a symbolic banner of protection, in much the same way that fanfiction writers used to declare they didn’t own the rights to The Vampire Chronicles or Harry Potter in the introductions to their stories.

Both statements reflect a vague anxiety about wrongdoing and legal consequences, and are ultimately useless: there is no stopping a dedicated 14-year-old from reading the cuckoldry stories you’ve posted online in a public venue, just as there was no magic phrase that could keep Anne Rice from coming after your site.

Surely every person who has been a kid on the internet knows that the phrase “Minors DNI” will do nothing to prevent a sufficiently curious and dedicated teen from digging for the information or smut that they desire. When I was doing my own straight-porn-exposure bonanza in my teenage years, I had to check a box on the porn sites stating that I was over the age of 18. I lied, and I showed absolutely zero respect for a law that denied I was a full person with the ability to determine what knowledge I was prepared for. The world of sex and adult expectations was barreling toward me whether my asexual self wanted it to or not; I had to be prepared, and I’m glad that I prepared myself.

There is no enforcing an 18+ policy on the open internet. And an internet that collected enough user data and had enough control over user behavior to actually enforce a strict “Minors DNI” policy would be a very dangerous and oppressive one indeed.

So we all know that telling minors to scurry away from your blog does not work.

But one thing that a “Minors DNI” statement does accomplish is broadcast to all young people that the user is not a safe adult for them to approach. If they have questions, if they’re queer and exploring their identity, if they’re isolated or neglected and need help, it does not matter — the adults on the internet have loudly turned their backs on them, so fearful of being accused of harming kids that they refuse to ever help them.

“I’m so sick of the way it’s become default to put ‘minors dni’ on your socials if you’re trans,” writes my friend, a fellow deer on the internet. “Individual people can make whatever individual excuses they want for it, but collectively we’re signing trans youth up for isolation, abuse, and suicide.”

Most transgender kids grow up not knowing any other people like themselves, and can’t be sure their loved ones will accept them should they come out. Less than a third of trans youth say their families are very supportive of them, according to the Human Rights Campaign, and according to the Trevor Project, roughly 40% of transgender youth experience homelessness because their families did not accept them.

Nearly 80% of transgender youth report being bullied at their schools, and thanks to the spread of laws banning youth access to gender-affirming care and the growing political movement of trans hate, we can expect for the rates of trans youth isolation and suicidality to rise.

It is difficult to be a queer kid in this world — to even ask oneself privately if you are a queer kid. In many parts of the United States, discussing any queer topics in schools is illegal, and parents affirming their children’s gender identities is too. Where is a questioning or closeted child to turn?

When I was a kid, same-sex marriage bans were sweeping across the country and the culture was mired in violently homophobic rhetoric. But at least we had the internet, a secretive and lawless space where bisexual strippers blogged about their hustles, gay truckers documented their trysts at rest stops across the country, and early trans sites like Susan’s Place and Hudson’s Guide introduced multiple generations to the basics of getting started on HRT.

These websites were beyond flawed, but they granted young queer people direct access to life-saving knowledge and a community of others like them, and to me, visiting them felt like gulping fresh air from a crack in the world’s shell. Back in those days you could find a trans mentor or gay pen pal and exchange emails with them furtively for years, their messages a lifeline through every bleak and empty day.

But if a trans teen went searching for such support today, on the modern internet, they’d find themselves blocked by members of their supposed community in a heartbeat.

In some cases, queer adults turn downright hostile toward young people that seek out their social media pages, and behave as if they are the ones being preyed upon when “minors” interact with their pages. Back in my own sexual content creation days, I was friends with a woman who took lewd (but not explicit) photos of herself in lacy underwear and socks. At one point she discovered one of her followers was a loathed minor, despite said minor claiming in their bio to be 19.

(Just as young people can ignore DNIs, they absolutely can practice the time-honored tradition of misrepresenting themselves. I would know, my sister and I both masqueraded as 20-year-olds on There.com when we were barely in the double-digits.)

“I cannot believe that a minor would gaslight me and violate my boundaries by claiming to be an adult when they aren’t!” the woman complained. “To the person that has done this, I hope that you know you have put me in very real danger! You have abused my trust. I hope you are ashamed.”

It struck me as absurd that an adult would think she were the powerless one in this scenario, and claim that she was violated by a young person merely viewing her public site. A cultural norm that supposedly existed to protect children from predation had somehow gotten flipped on its head, the minor cast as the predator, the adult (who risked nothing but the accusation of impropriety) now the ultimate victim. This adult woman believed it was the responsibility of the child to enforce the rules that the adult had set, when the only consequence for that rule being violated was that the adult could suffer.

It was bizarre. And yet, in the years that followed, I would go on to see numerous adults framing interactions with minors in exactly the same way — as an unwanted intrusion, as a threat to their wellbeing, the mere presence of a child in their midst some kind of terrible attack. Over time, as kids continued to do what kids do (search for knowledge, break rules), people’s DNI statements got even more harshly worded:

“Minors FUCK OFF”

“Minors I will bite you!”

“I HATE CHILDREN! You are not welcome here!”

“Minors GTFO!”

“If any minors try to follow me I will make you cry!”

I wonder if any of the people with these bios have ever paused to think about where the word minor even comes from — persons under 18 being the most literal of minorities, decreed under law to be less of a human being than anyone past that age.

A “minor” is not defined as a person who is young or uniquely pure, but as a person who cannot own anything, who cannot vote, who cannot decide where they live or whom they live with, who does not have the power to consent to medical procedures (or to revoke consent), who is the property of their parents when they are at home and the temporary property of the school when they are at school, who can be beaten by their “owners” and denied freedom of movement or food to a degree that is only otherwise permitted with the imprisoned or enslaved. Legally and socially, the similarities between a minor and a prisoner or a slave are almost absolute.

Being a minor is a position created by legal oppression, but most people consider a minor’s lack of freedom to be so natural and morally correct they don’t even recognize it as oppression. Instead, they see it as protection, a healthy separation between the world of the human and the not-quite-human yet. Though they would never admit it, a minor is not the same thing as a person to them, for a minor can be thrown out of public spaces, locked away, silenced, disregarded, and left to rot in the ways full persons are not.

I believe that we queer adults are failing our younger siblings by refusing to play a part in raising and looking after them. We have chosen to privilege our individual safety from accusations of ‘inappropriate’ conduct over the need for queer youth to see their own sexualities and identities normalized, envision a diversity of possible futures for themselves, and seek aid and understanding when they are mistreated.

For those of us who’ve had the liberty to escape our ignorant hometowns, get on HRT, have joyous gay sex in dark rooms, or even just dance tenderly with a sexy androgynous stranger’s cheek pressed against our own, we have a responsibility to pour from our filled cups, and to remember what it was like to have no such access. As terrified as we are of losing our documentation, our access to medicine, and our legal rights, we must remember those queer people who presently have none of those things, and do all that we can to extend our aid to them.

Our freedoms grew from the efforts of ACT UP activists, ADA protestors, cruisers, sex workers, pornographers, runaways, and all manner of brazen, unrespectable queers and societal outcasts. Don’t we realize they were accused of being predators, groomers, and recruiters, too? Are our memories that short?

Would Allison Bechdel have ever had her formative “ring of keys” moment of realizing she was queer if there hadn’t been a butch woman proudly swaggering in front of her at the diner, in defiance of every social rule that said at the time it was perverse for a woman to dress as a man?

Trans female content creator Mardi Pieronek transitioned at age 15 in the 1970s, thanks to the help of other trans women who were working on the street. Imagine if those sex workers had shied away from her, and chosen not to share the miniscule amount of freedom and access they had and that she lacked. If people who had so little and were so vigorously oppressed were still able to love young queer kids generously and show up for them, why can’t we do the same?

Even outside of the queer internet, expressing complete disinterest in the wellbeing of “minors” is quite normalized. A performative distaste of being around children, talking to children, or looking after others’ children has become the default among many queer and child-free people, who seem to be projecting their own hatred for the restrictive nuclear family onto the people still trapped inside one.

It is an instinct that I understand. When I was younger and looked like a “woman,” I hated that people saw me as a future incubator for kids. Sometimes I found it enraging to be around children, because it came with the expectation that I take on a motherly role that I did not want. I’d found my quiet, suburban life within my family to be stultifying, and saw taking responsibility for children as a shackle that could keep me trapped in that kind of life.

I Feel Broken for Not Wanting Kids

The world didn’t teach me what a happy childfree existence looks like — so I will have to teach myselfhumanparts.medium.com

But now that I am older, I understand it is children who are shackled most of all. What I hated about my former social role as a woman wasn’t that it linked me to children, but that it was unequal, forced upon me, and was not what I wanted for my body. No one does well when they lose control over their life and their body. And there is no group that has less power over their own lives and bodies than kids.

I hated that when people saw me, they wrote onto my body the expectations of motherhood and straight marriage, but I was able to escape that; no kid has the power to escape being a minor, and doing whatever their parents make them do. All they can do is wait.

I want to be someone who can help young people wait out those hard, lonely days of being a minor, and not feel so alone in this world. I remember how finding secret stores of knowledge on the internet lit up all of my brain, how my friendships with older people saved me. I kept every compliment that an adult ever gave me in a big document file on my desktop when I was a kid. Most of those compliments were about the great potential they saw in me, and how persuasively I expressed myself.

“I love your work, it is punchy and precise,” said Erich, the man who ran the blog I contributed to when I was 16.

“Is a career in writing in your future? I sure hope so,” said my tenth grade English teacher.

“It is rare to get to interact with someone who has such a unique way of viewing the world,” said an older gay man that I met on Myspace. “Please never stop sharing what you have to say.”

“You’re hilarious,” said Ana. “I wish I had been so confident when I was your age.”

I didn’t always know what those words from adults would mean for me, but I followed them — and in time, they led me to the wonderful life I now have. Why would I want to leave everyone that comes after me behind?

Like many white Americans, I’ve often foolishly seen freedom as the complete absence of responsibility. For the longest time I believed independence was the only way to escape all that I’d been made to do, forced to be, and prevented from being when I was young.

I realize now just how ridiculous that understanding of the world is. I have always relied upon other people to stay fed, housed, looked after when I am sick, to mentor me, to believe in me, read my writing, tell their stories to me, challenge me, and simply be there. I am nothing without them. They are in my brain forever, and when I speak to someone and pass on what I know, their guidance lives on.

I have to be there for the next generation of queer children, even if I am not a parent, perhaps especially because I am not one. I do not lay the claim of ownership upon anyone. I remember how imprisoning that felt. And for those who are still stuck and suffocating, I want to crack a hopeful hole in the side of the world, and let some air come rushing in.

So what should we do, if we hate our society’s segregation of “minors” and want to fight back against it? I can’t say that I have all the answers, but I can share some of the things that I do, and that people I admire do.

I don’t monitor the ages of people that access my sites or my writing. I provide information, especially information about queerness and sex that I feel is needed, and for which access is quite limited in our current environment. I do this freely and without gatekeeping.

I do not use paywalls or require people to register or provide me any personal information in order to read my work. Accessing the information comes on their own terms, only engaging further when and if they decide to do so.

I trust people to determine for themselves what information they want to know. I try to follow the same principle that a cousin of mine did when raising her kids: If a child is old enough to ask a question, they are old enough to receive the answer.

If a young person wonders about sex, death, drugs, violence, or other “adult” subjects, that means the subject is already on their mind and weighing upon their heart. Dismissing their concerns does them no favors. Asking questions shows agency, and providing answers to those questions is a sign of respect. I do not think knowledge does harm.

I also trust people to decide what they are not comfortable consuming, and to curate their own experience online. Boundaries are expectations that we maintain for ourselves using our behavior — we cannot expect any other person to intuit them or enforce them for us. Each person’s triggers, limitations, and squicks are different and cannot be anticipated by me.

In my writing and social media posts, I speak of sex and past traumas quite freely — and if a person of any age does not wish to see that, they can see themselves out. I make it pretty clear from the outset that my work contains mature themes and I do use content warnings when I am able, but ultimately, I don’t behave as if another person’s feelings or reactions are something I can or should control.

I also do not think that having an uncomfortable feeling for a moment is a violation. More often, it is useful information about oneself that can make it easier to set boundaries in the future.

I do not believe that a person is harmed or traumatized when we acknowledge difficult topics that already exist in their world. Children live in a world that features abuse, sex, genocide, structural racism, transphobia, substances, death, and ableism. Treating them as if they are too fragile to cope with these issues does not prepare them for life. Through learning and speaking about such subjects frankly, we become more able to regulate our distress and cope with them.

Many young people find their first glimpses of death, sex, and similar subjects to be memorable and shocking, but this does not mean it is a violation to walk in on mommy and daddy being intimate with one another, or to view a corpse at a funeral. Similarly, if a child stumbles upon my blog, I think the worst thing that can possibly happen to them is that they have learned something new or been confused. Those are emotions we all routinely experience in life.

I aim to treat sex neutrally. Sex Exceptionalism is a belief system that treats sex as completely separate from all other human activities, and filled with an almost supernatural potential to harm people or change their lives. This worldview makes it very difficult to educate young people about sex or discuss any topic even loosely related to sex in public.

Instead, I try to treat sex as just a regular facet of everyday life: you might need medical care involving it, sometimes it might be uncomfortable or awkward, it might require some accessibility tools to enjoy, and sometimes it comes with some risks, but at the end of the day it is just a thing people can do together if they like.

While I would caution young people against engaging in particularly risky sexual activities such as full-body rope suspension (in much the same way I’d discourage them from slamming FourLoko, or skydiving), I remain aware that young people do have sex with one another — because they want to do so, and often enjoy it — and I don’t consider them too “pure” to be informed about the workings of their own bodies.

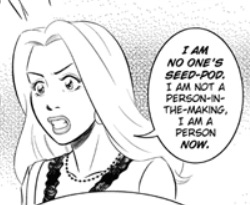

I treat young people like full human beings. As one of T. Campbell’s adolescent protagonists once told her parents, “I am not a person-in-the-making. I am a person now.” I try to hold onto this perspective whenever I interact with somebody younger than me.

Young people have their own experiences, opinions, tastes, emotions, insights, inner lives, and personal evolutions I’m not privy to from the outside, and none of it’s my business unless they decide they can trust me with it. I see young people as my neighbors and comrades who have plenty to contribute that I can learn from. I try not to project my own complicated feelings about my past or my regrets onto their lives, which are theirs to live.

I err toward keeping my digital interactions public, educational, and non-parasocial. Because I am a public figure whose privacy has been invaded many times, I do not chat privately with complete strangers much at all. I think that’s where interactions between adults and children have the potential to become the most fraught and troublesome.

I also do not believe it is appropriate for me to use random people on the internet that I have no deeper relationship with to satisfy my emotional or social needs, which means I keep pretty firm boundaries in what I talk about and how. I am not here to be a complete stranger’s best friend and I don’t get overly familiar, and I try to keep whatever is going on in my personal life separate from my work.

I do not enforce laws or social media policies. Meta and me are not on the same side. I will use the words sex, genocide, and rape without the funny mispellings that appease the censors, I’ll happily explain how to shoplift for survival or put on a condom even if doing so is against terms of service, I’ll spread links to sites where people can DIY HRT, and I will not enforce content restrictions that I did not decide upon for myself.

I’m not afraid of the consequences if a minor uses my advice to get on hormone blockers or start taking PreP; I have gladly accepted the risks of what I consider both a personal calling and the correct thing to do. Fascism spreads more rapidly when frightened individuals comply with evil laws in advance in order to spare their own skin, and I won’t let myself be a tool of oppression.

I work on my own prejudices against young people and children. We all live in an adultist society that primes us to dehumanize kids, and lord knows I have my own baggage involving childhood trauma and caregiving expectations. But my wounds are not any kid’s responsibility, so I really try to approach young people with a clear frame of mind and to remind myself that I am safe, I have control over my own life, and I hold a hell of a lot more privileges than they do.

Thanks to the writing of child liberationists, I understand that a child screaming on the bus is not a sensory assault against me, but a disturbed, powerless little human trapped in a situation that has overwhelmed them. When a younger person doesn’t know how to complete a task or does something that makes me cringe, I try to remember this is their first time on the planet (and it’s mine, too). I know that I do not have a right to not be annoyed, and that freedom does not come from a lack of responsibility towards others. True freedom comes from no longer relying upon authority figures, and having a robust network of support.

Raising a small kitten has done a lot to improve my attitude: so many of the behaviors from my cat that annoy me or get in my way are caused by an unmet need, so rather than getting angry with her for scrambling all over my desk, I can just give her the enrichment her little growing body craves. Usually, taking a break from what I’m doing to chase one another around the house is just what I needed, too.

Appreciating the needs of young creatures in my life means moving more patiently, aspiring to get less done, explaining what I am doing carefully, and sometimes just speaking out loud to myself about what we all need, to remind me of what chaotic little animals we all are. Children are unruly because they haven’t been fully conditioned into compliance yet; some of their most irritating or disturbing traits are them at their most free, and I can learn a lot from their “rude” questions, openly curious stares, defiant tantrums, and willingness to break rules.

“I am child-free, which means I have a responsibility to look after all people’s children and treat them as if they were my child,” I once heard my friend Vowel say. “How could it be any other way? Who is going to look after the young people in my community if I don’t?”

Who, indeed. Far too many queer adults have been choosing to abdicate our collective responsibility toward younger generations. But we cannot do so any longer. Online, queer stories are being silenced; in our schools, queer history is being erased, and across the planet laws are passing that make it harder for LGBTQ individuals to freely use our bodies and connect. We cannot allow our most powerless community members — our children— to be pushed further into the dark.

So please. Interact with minors. Doing so might cost you just a little time, but to them it means the world.

I really wish I had had this article a couple months ago. I help run a (pretty small, pretty queer) discord server for authors of fan and original works inspired by a specific manga, and we instituted a 18+ rule not only for reasons of discussing sex and abuse and everything else that comes with the territory of the specific work we're fans of, but also because well, like, teenagers are often kind of cringe! and there's a desire for a kind of adult discussion, especially because it's mostly people in their late 20s and 30s.

I'm a 25yo trans woman, and it turns out that a young trans woman from Eastern Europe who had joined was 17: she'd simply missed the part where the server name and rules had said 18+. and she really obviously desperately needed the community but when she accidentally let slip that she was 17 I ended up pressured to remove her basically for everyone else's comfort. There's more there but it's not important. Things have shaken out where I have a little more power and say now.

Unfortunately the winter is usually hard for me anyways and I didn't have the words, at the time, to make the case for why she should be allowed, and I wish that I had been stronger in that moment. she's owed more from all of us than exclusion for everyone else's comfort, and she's owed more from *me* specifically. I don't want to let myself be weak like that again.

This is a good article and it hits very close to home. thank you.

Thank you for this, Devon. Deeply and sincerely, thank you.

I look back fondly at the anime groups and kink-friendly spaces that helped me understand and revel in my own proclivities. There was such a lack of shame, ridicule, guilt and fear in those spaces in the aughts. It wasn’t until just a few years ago that I was confronted with blocks, bans, blacklists and the like for having an unpopular ship or not having the right virtue signal phrase in my bio. It’s so strange to be fully in my 30s and feel the need to tiptoe around increasingly censorious social codes. If I’m feeling the creep of Purity Hypervigilance I can only imagine how a middle schooler feels.

It cannot be understated how nefarious and powerful the advertiser-friendliness aspect of this whole deal is. When I worry about kids online today it’s not because of any NSFW content they might see — it’s because their brain development is linked inextricably within a digital context that is built to maximize extraction of their time, resources and money. We all grow up influenced by manufactured consent under capitalism to some degree, but the opacity and omnipresence of the sculpted realities kids are subject to freaks me out.

On a relateted note, I recently moved to a rural area and have wanted to do some organizing, particularly youth outreach for LGBTQ+ kids, but have no idea how to attract the attention of at-risk youth without raising the suspicions of hostile parents, pastors or other adults who would accuse me and my trans/queer friends of scouting out kids to corrupt. If anyone has any youth organizing ideas, specifically in conservative areas, I’d love to talk about this.