You’ll never really know, know-know-know, know-know-know

Anything about me, me-me-me, me-me-me.

I met him on Fetlife, “the world’s largest and most popular social network for the BDSM community,” in a gay hookup group.

Already I am feeling self-conscious about writing this, because the last essay I published also opened with a personal story about my sex life. I wrote and published a highly revealing piece about my transition and genital preferences two weeks before that. If I keep writing so much about sex, and my personal life, people will view me as superficial and internally empty.

I fret all the time about what kind of splash my writing will make, when it comes out, and the accumulated effect of all my work when it is considered together. I am never not replaying my words and analyzing how they might come across to another person. I’m constantly running a simulation of the judgments people will make about how I spend my time, where I put my attention, and what I choose to say to the audience I have cultivated.

I would be a fool not to consider these things. If I did not think about them and pre-empt them, often in quite a calculated way, I would not be where I am.

And so, if I were to be calculating, I would separate two essays about sex between a staid, neurodiversity-focused how-to, to break up the flow of posts and maintain my branding as an approachable person with expertise readers can hold in high esteem.

But this essay isn’t really about sex, it’s about how being a public figure taints everything, and why I feel increasingly compelled to destroy my “brand.” One of the inciting incidents that gave me this compulsion involves sex. And so a personal sexual story is where I begin.

I made a post in the Fetlife group, looking for a Dominant who would be interested in tying me up or enacting a hypnosis scene with me. One of the first replies came from a tall white guy, about my age, with short hair and long hands. He said that he’d eagerly read everything on my profile, that we shared many of the same kinks, and that he was Dominant and excited to try some hypnosis files with me.

There was relatively little information on his profile, though he’d clearly been using the site for some time. His bio indicated he was a switch, and quite open to playing with trans guys. He also described himself as “orally inclined.” That latter detail is typically a no-go for me. But his messages showed care, and his desire to Dominate me seemed genuine. So I invited him over.

I knew pretty quickly that we wouldn’t be a match. He didn’t put out a Dominant energy; mostly what he wanted to do was chat, hit poppers, and kiss. He listed off his many recent sexual exploits, which ran the gamut from fisting, to white-inferiority-themed threesomes, to Daddy-son roleplay, and I couldn’t see myself reflected.

But I also really liked him. He was chatty and effusive, and very intellectually engaged. He made an off-hand reference to bell hooks’ The Will to Change, then said to me, “I’m sure you’ve read it, right? I’d be shocked if you hadn’t,” before peeling off in exciting new conversational directions, about his past political organizing work and his Master’s thesis on the history of Uptown.

He also possessed encyclopedic knowledge about the Midwest’s many disparate gay scenes. He enjoyed connections to the Hellfire Club, as well as the Radical Fairies. He’d been with many trans guys before, but expressed to me his disgust at the fact many gay cis men are “collectors” of sexual partners who might be seen as novel.

“Everyone is trying to fuck their first porn star, their first trans guy, their first famous person, all just so they can say that they’ve done it,” he said.

He spoke a mile a minute about a lifetime’s worth of social data that he had painstakingly collected, always looping me back into the discussion with a knowing ease. It seemed as if we’d known each other for longer than we actually had. His manner was so cute and the conversation so engaging that I decided I might as well drink a few White Claws, hit a few poppers, and roll around in the bed with him, incompatibility be damned.

We had sex on and off for about four hours, with intermittent breaks for conversation. Sometimes the chatting continued as we rearranged our bodies, me sliding up and down atop him, him parting my legs on the couch. The sex I didn’t find exciting, but it felt good to get along with someone so immediately, all without any effort on my part.

At one point he was down in between my legs, fingering me, and he made a throwaway comment about probably being Autistic.

I leaned back, trying to relish what pleasure I was getting. “Well, we can talk about that subject, if you like,” I said vaguely, not really wanting to bring my professional life into things.

He kept working away at my body, kissing between my lips and thighs and then working his mouth between my legs. “Oh I know who you are,” he said suddenly. “Your book changed my life. In a way, I guess this is me thanking you.”

I made him exit my body and we went to the kitchen to hash it out. It turned out he was a big fan of many things I’d written.

“I’ve seen you around the neighborhood many times,” he confessed. “But you posted online that you don’t like when people come up to you, and so I always decided to leave you alone.”

He said, “Your book is the reason I got divorced, actually. My ex-husband was a therapist, and when I showed him your book and said I thought I might be Autistic, he didn’t believe me. We have been separated for a year.”

He asked, “Did I just make this weird, telling you when I did that I was a fan?” I told him that if he’d said it sooner, I would have never fucked him at all. He left quickly, placing his leftover White Claws into his backpack and jutting out the door with his eyes locked ahead.

I sat back down on the couch, which was still wet from our bodies, and realized that he had been one of the very collectors he’d warned me about, and that he had collected me.

When we’d first been chatting, he’d shown me some of his favorite trans masculine porn stars on Twitter, and asked me if I knew any of them personally. It was a question I’d found bizarre (you really think we all know each other?), but shook off. Now I realized that in his mind I was in the category of famous trans people, two boxes he was more than happy to check off on his list of conquests.

He wasn’t a Dom either; that much had been clear. In fact, his primary focus during the encounter was on getting closer to me in whatever ways he could: feigning shared interests, asking my opinions on books, info-dumping about subjects I had already written about being interested in.

The dread and disgust I felt curdled into anger. He was only interested in the public figure Dr. Devon Price, and he’d been willing to misrepresent himself and manipulate me to get access to it. Now he knew where I lived, had my phone number, and had revealed to me that he was firmly planted within some of the city’s primary kinky cliques.

I didn’t leave the house for the rest of the day. Instead I just laid around and chatted online anonymously with strangers. The next morning, I took a side street to the grocery store with my sunglasses on and big chunky headphones covering my ears.

A young woman’s eyes lit up as I passed her on the sidewalk.

“I’m so sorry to bother you,” she said quickly. “But your books changed my life.”

I flinched.

The long-handed man from Fetlife was far from the first reader to push past the real me’s boundaries, trying to make contact with Author Dr. Devon Price.

There was the Autistic twenty-two- year-old who pushed through the crowd at the leather bar to stim excitedly at me, while I stood, confused and drunk, in nothing but a thong and a harness. There was the bleach-blond enby who talked with me about the band Coil because of the logo on my shirt, who only shared after half an hour that they were obsessed with my Instagram. There was the person online who sent me erotica they’d written in which I fucked another semi-notable trans guy.

I’ve been recognized in unusual places, like a Joe Perra comedy show and the audience of Killer Mike’s Pitchfork set. I was recognized in a Target, buying multivitamins two hours after leaving the operating table the day of my top surgery. The next day, someone asked me to sign their copy of my book while I rested outside, bleeding into my drains.

At times, I’m made aware that my words have a significant influence on the outside world: a drag queen reads an Instagram post of mine in a bar, to cheers, and I get told about it. A complete stranger says he moved to the city because of my posts about cruising in Chicago’s gay bars. A teenager at Pride says they’re writing a paper that heavily quotes me.

Most of the time, people are complimentary and polite, and have done nothing inappropriate whatsoever. But when taken altogether, these experiences make me feel surveilled. I realize I can never have a bad moment in public. Though I am clear in my writing about being socially disabled and insane, I can’t lose my faculties anywhere someone might see. I can’t even lose my speech temporarily, or become shy. The people who say they’ve read my books three times over might think I was being ingrateful.

I can’t even go to therapy — the only providers who are competent in working with Autistic adults are ones who have read my work. They show up at conferences, thanking me, telling me that they pass out my books to their patients on a regular basis. Then they ask me for advice, often of the personal kind. If I were to sit across from them in a private office and express my true feelings, and talk about my real problems, they would be repelled. I have to keep my distance so they can continue to appreciate the idea of me, and access what benefits the book apparently offers. In this age of identifying with what one consumes, a useful resource can be tainted through its association to an author who is at all flawed.

A man emails the President of the university about me every single day, trying to get me fired. He’s done so since I began speaking openly about being pro-Palestine. In the comment sections of Youtube videos in which I appear, I am called a eugenicist and a transmisandrist. Sometimes people who are associated with me get caught in the blowback. I avoid acknowledging these problems usually, because that is the strategic, safe thing to do. If you acknowledge a stalker, they will only feel rewarded and escalate. And setting out to disprove harmful rumors about you only means those rumors reach thousands more ears.

There are real consequences when the real me does not meet the expectations laid out for Dr. Devon Price. Once, at a queer munch, a butch woman ran up to me waving and called out loudly in front of everyone, “I know you!” When I asked back, sincerely, “Do I know you?” she folded up on herself with embarrassment.

I didn’t mean for the question to be as mean as it sounded. I never went back to that event again. There are entire neighborhoods I avoid because I can’t walk them without being recognized, and I can’t count on myself to always be “on.”

I’m bad with faces. I can’t feign enthusiasm. In public, when I am feeling overwhelmed, I’m not particularly patient or warm. I’m candid about my most difficult qualities in all of my books. I can’t see how anyone could understand what kind of guy I am and still look up to him. Yet people still want someone like Dr. Devon Price to become their therapist, teacher, or friend.

My writing, people say, makes them feel seen. But I have not ever seen them. I have only seen myself, and the handfuls of subjects I’ve interviewed, whose experiences I can render in writing pretty well. My work creates the illusion that I am in the reader’s head, and for this I feel like a fraud. I’ve never been able to understand anyone’s head but my own.

It’s just a coincidence, it seems to me, that my self-involved nattering makes so many feel less alone. I am cursed by my lack of empathy to forever be a solipsist, and I do not deserve praise for any of it. Especially not when my success is built upon so many people’s pain. Lonely, adrift people shill out $28 for the privilege of reading a book I wrote when I, too, was lonely and adrift. Why should I get to profit from these emotions while others have to pay?

The more people compliment me for my sensitivity, compassion, and endless understanding, the more I hate myself for what I know really lies within. And in a way I hate them, too, for making me confront it.

Last month I read (and profoundly enjoyed) Sally Rooney’s 2021 novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You?, a book which is at least partially inspired by the author’s real-life experience of becoming a literary darling at a young age and while shying away from her own fame.

Beautiful World’s protagonist, Alice, is herself a novelist who rose to international prominence shortly after leaving school, and has since experienced a mental breakdown and retreated to a quiet seaside town to lead a reclusive life. For the first several weeks that she lives in the town, far away from her best friend Eileen, Alice doesn’t speak to a soul.

On a Tinder date in the novel’s opening scene, Alice plays coy about what she does for a living. She tiptoes through her growing relationship with the blunt, unimpressed Felix, as if afraid of introducing the massive weight of her public identity into their growing relationship. She’s tense and sarcastic when he discovers that she has a Wikipedia page, and seems defeated when he finally asks her if she is a millionaire and she has to answer yes.

Alice falls in love with Felix quickly, in spite of his almost unrelenting mockery of her. What she seems to like most about him is that he approaches her as something of a blank slate. He hasn’t heard of her, and doesn’t care to read her novels. Even after learning of her notoriety and traveling with her on a book tour abroad, Felix remains unimpressed, and stresses to her that his job in a warehouse is endlessly more difficult. Alice agrees, and enjoys that dating Felix gives her the opportunity to mix with the locals in town and be among regular people, relatively unremarked upon.

I’m nowhere near as famous as Alice is written to be, nor Sally Rooney for that matter, who has sold three million copies of her books. I can’t purchase a retired rectory on the Irish coast, and outside from a few queer neighborhoods in a few major cities, I can find anonymity. Still, I identified with the chilly, self-mocking Alice, who treats both her public-facing self and the world that knows of her as loathsome adversaries.

Like Alice, I have made a habit of not telling new people what I do for a living. I just say that I’m a teacher (which is true). In casual conversation I avoid all mentions of either writing, or Autism. I do not mingle where I’m likely to find fans of me: trans-for-trans cruising nights, neurodiversity panels, and the like.

When I hit it off with a new crowd and the well-established Zillennial ritual of trading Instagram handles occurs, I have to give out my phone number instead. I have noticed the light shifting behind people’s eyes when they see my follower count. I don’t like when they like me more and defer to me once they’ve gotten acquainted with my alter ego.

And besides, I can’t see any of their messages on Instagram anyway. I had to turn off all notifications years ago.

I learned to set better digital boundaries with my readers thanks to the work of Abigail Thorn, a trans woman writer and actress who runs the Youtube account Philosophy Tube.

Thorn has written a lot about how she keeps her own fame at arm’s length. She has an explicit policy of never dating a person who is a fan of her work, for example, which I intimately understand. She has been stalked outside of theater performances and work functions by obsessive admirers and sent threatening mail, experiences I know all too well, too.

Because she exists in the public eye on such a large scale (and because trans women are subjected to the most intense of misogynistic fan scrutiny and entitlement), Abigail Thorn has all social media notifications turned off for anyone that she doesn’t know and already follow. That means that if a random stranger starts spreading lies or vitriol about her on the internet, she never even sees it.

I adopted this same policy for myself, because I saw how much it insulated Thorn from the transmisogynistic hate mobs that have often been sent her way. It’s also kept her from descending into the kind of resentment that so many popular digital creators fall into, once they’ve run afoul of former fans often enough. She has a policy of never speaking publicly about any individual in a negative light; I’ve found it hard to locate the resolve to do this.

I have, though, elected to turn off the comment sections on all my social media pages. I realized a long time ago that I don’t have the time to read and moderate feedback I received from thousands of people per day, and that frankly, I also don’t care to receive it.

Of the over ninety thousand people who follow me on Instagram at the moment, I only personally know a few dozen. I don’t trust the judgment or intentions of any of the rest. I don’t know what informs their opinions, and what motivates them when they ask me to change what I’m doing. Most of the time, I can’t even trust they’ve read whatever it is they’re commenting on. And so I do not engage, shuttering the doors to the entity that is Dr. Devon Price so that no one may enter but me.

Abigail Thorn’s videos about parasocial relationships inspired me to ponder what kind of relationship I wanted to have with my audience, and the answer, it turned out, was not much of one at all. It’s not even really because of any fault with them. I’ve met a lot of my readers, and most of them are unfailingly thoughtful and kind. The real problem is with me, and with the kind of a person that any public entity must become when they are admired and spoken to by thousands every day.

Beautiful World features emails exchanged between Alice and her best friend, a literary editor named Eileen. In her messages, Alice disparages the obligation that authors publicly sell their work. She says that traveling, giving interviews, and being photographed for magazines only takes her away from the one solitary activity to which she is best suited, writing, and describes people who chase fame as deeply psychologically ill.

Voicing Alice, Sally Rooney writes:

I keep encountering this person, who is myself, and I hate her with all of my energy. I hate her ways of expressing herself, I hate her appearance, and I hate her opinions about everything. And yet when other people read about her, they believe that she is me. Confronting that fact makes me feel I am already dead.

Of course I can’t complain, because everyone is always telling me to ‘enjoy it.’ What would they know? They haven’t been here.

In the novel’s climax, Eileen questions Alice about her choice to move to the secluded seaside permanently. In a fit of rage Alice claims that her dear friend has done nothing of value with her life, screams that it is impossible for anyone else to understand her, then shatters a glass on the floor beneath the sink and threatens to commit suicide with the shards.

The only person who can console her is Felix, who has also experienced suicidal meltdowns in the past, and reassures Alice that he is not afraid of her. For all of her wealth and acclaim, and despite the highly intimidating figure that she cuts across every scene in which she appears, Felix does not fear Alice. When he looks at her, he sees an ashen-faced woman standing in her kitchen, in the middle of a complete collapse, not the famous author Alice Kelleher. And that is what saves her.

A close friend comes to stay with me for a long weekend. I tell her about the guy from Fetlife, and the hundreds of other readers over the years who have meant me no harm, but still pulled me out of my inner privacy and onto some unending stage.

People never realize that when they approach me, what they are doing is dragging me into work. It doesn’t matter whether I was at breakfast, or an orgy. I was just some guy standing there, enjoying his beer, but now they have made me the known scholar and author. And sure, my job might be meaningful, but that doesn’t mean I like to work.

I tell my friend that I no longer want to be a public figure, and that I am planning how to make it all end. She tells me, “You’ve got to do what is the best for you, even if it’s something that the rest of us wants and can’t imagine giving up.”

I ask myself, did I want this? It would be more flattering to say I didn’t, and play the role of the hermetic author whose work developed its own life purely because it was so good. But that isn’t true.

From the moment I got a Myspace account in high school, I was publishing essays about my political views. I serialized multiple novels on Tumblr, guerilla marketing them with giveaways and custom-made images until they hit the Kindle sales charts. I have made memes, tried starting viral trends, coined phrases, and given hundreds of hours’ worth of media interviews. I write prescriptive nonfiction, for Christ’s sake. Of course people seek guidance from me. I offer it up!

I have been strategic about how I dress, and my video backdrops, and retaken clips of myself speaking over and over again until they sounded right. I’ve hosted debates with my most vicious critics while I’m in the shower, started public beef with creators who had larger accounts than I did, and rushed to my keyboard when upsetting news broke, because I alone was possessed of the most correct take on it.

I wanted this. I didn’t know what this was, this internet fame I was chasing, but I did all I could to make it mine. I thought that by writing so much, I would one day be able to escape myself, maybe really feel connected to other people. Instead it has meant never being able to stop thinking about myself: how I am seen, what I am working on, how it all fits together, what comes next. It has also meant being spoken about, theorized about, and criticized, and developing a firm exoskeleton of disdain between myself and the world.

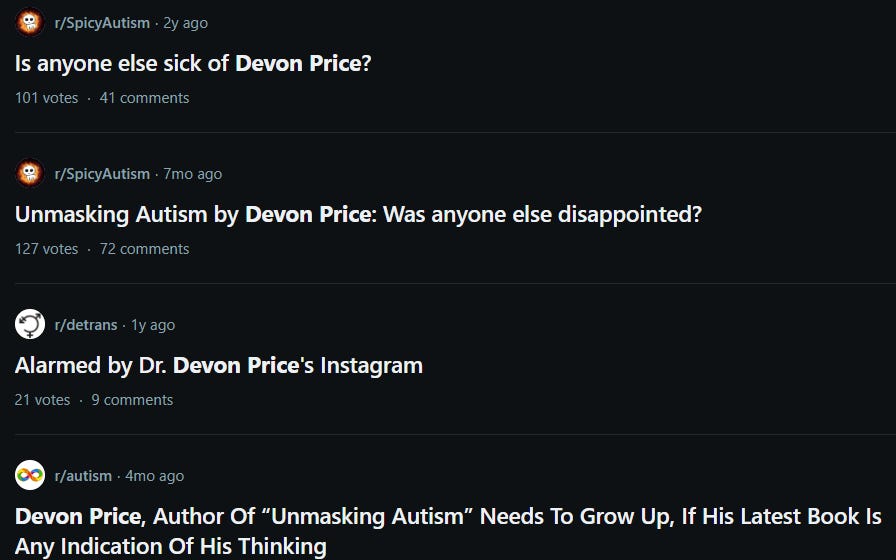

Every now and then I’ll receive a message from a former reader who wants me to know why I’ve lost their support. I failed to account for all possible human experiences when writing about my own life and feelings, say, or I used a phrase they consider unforgivable but which I have more mixed feelings about (like “stupid” or “crazy”).

Whenever someone like that tells me that they are “disappointed” in me, my first reaction is to think, Good. You never should have expected so much from a person you don’t know. I feel glad they are living in reality, now, rather than projecting their own perspective onto an outline of me on the wall.

I used to feel compelled to go online and explain every little thing I ever thought or did. If everyone in my social circle all held the same opinion and I was convinced they were wrong, I believed I needed to fight day and night to articulate my position and bring them over to it. I thought I needed to “save” them, I really did.

These days I catch only glimpses of what people fight about online. I imagine allowing everyone to drown themselves with their exertions while I float downstream. I don’t want to be seen. I don’t want to be understood. There is a power much older than social influence, and that is the power of mystery. I no longer want to be a leader, moving vast keyboard armies to enact my morals. I want to sink into the muck and let nature, in all its yawning indifference, overtake me.

I stare into my chinchilla’s eyes. And I see the vast, beautiful nothing inside of him. It helps me to access the amoral and animal inside me, too. He has no concern for the righteousness or wrongness of anything. He knows, without thinking, that these human labels don’t exist. He just responds to his urges and to his surroundings. His history, like the history of all living creatures, is one of great violence and hollow boredom. He chews his fur nervously. I leave anxious marks on my skin.

I walk the expanding nature reserve by Montrose Harbor, which was little more than an open lawn and a few trees when I moved here fifteen years ago. Now it is overgrown with tall native grasses and field flowers, all of them shaking with the movements of life.

A chipmunk hurries over to meet me, unafraid, seeking food. In the shade, at nightfall, men hold onto their cocks and look for one another. There is an animal wariness in all sets of eyes. Everything is wordless. In each living being there is a universal mystery of equally enormous size. If I move slowly, I don’t shift the ground too much, and I don’t scare any creature away. I am there for what unfolds, a participant in the great shared living, but never an author of it.

I believe now that that it is immoral for any person to be listened to by ninety thousand other people. Holding authority and status like that runs counter to my anarchic ideals. I am not more important or correct than anyone. I should not be trusted to tell people which commodities to buy, which companies not to support, what to read, what to think, what words to use, or how to conduct their lives.

All the other animals know there is no one way that a creature “should” live. There is only the way that it does. The world has no consciousness, no beliefs. It cannot pass judgment. We only feel so watched and evaluated because we have covered the planet with so many millions of our eyes. But we can stop performing dignified human goodness at any moment.

I think that celebrity is an evil, corrupting force that pits the human instinct for bonding against itself. Instead of appreciating the singing of our friends around the fire, we stream Chappell Roan until stalkers break into her house. Rather than playing card games together, we stan Twitch streamers, filling up their chats with highlighted messages until they acknowledge us. We long to be famous novelists because then we would have the social permission to write, and we don’t have the money or time to enjoy the activity on its own.

I have heard some writers theorize that we no longer live in the social media age, but rather the age of stan culture. Social groups now coalesce around semi-famous figures, rather that platforms, and discussing, analyzing, and riding for those figures is the shared pursuit. Some people are Arianators, cutting together drone footage of Wicked into their fan cams; others worship Kate Middleton and theorize about her supposed disappearance.

And then there’s those of us who look to social justice influencers for guidance, subscribing to their newsletters, sharing their infographics, and modeling our lives around their political beliefs.

With our worship of celebrity, we imprint upon people who will never know or give a damn about us, and funnel all of our money to them, hoping to feel connected. When we imagine what being loved would be like, we think of ourselves having tons of fans and a huge platform, because we’ve never seen small networks of people just caring for one another, including the people they disliked. Human beings are so disposable that we long only to become a valuable product.

Chappell Roan recently took to TikTok to blast fans for invading her privacy, touching her without her consent, demanding photographs with her, and stalking members of her family. “I don’t care that it’s normal,” she says in the video. “I don’t care that this crazy type of behavior comes along with the job…If you saw a random woman on the street, would you yell at her from the car window? Would you harass her in public?”

She’s contemplating degrowing her own celebrity, stating on the Comment Section podcast that she wants to “pump the breaks” on her growing public profile, and that she promised herself years ago that if her notoriety every put herself or her family in danger, she would quit.

I do not know what degrowing my far smaller-scale celebrity might look like, but I find that refreshing: at last, it’s a choice that is not calculated.

I’m not checking social media at all. I spend a lot of time in nature willing myself to stop thinking, to be feral. I am working on a novel about a tormented blogger-turned-influencer who contemplates becoming a serial killer, a project that has made me enjoy writing for the first time in years, though it also feels like career suicide. I don’t have to slash my wrists, as Alice Kelleher threatens to do in Beautiful World. I can eviscerate Dr. Devon Price, the idea, myself.

A lot of the people who read my work are deeply buried under something. Expectations, social roles, guilt, stigma, old patterns, self-loathing. I thought before that I had an obligation to pull each one of these people out. Every time someone told me that my book had saved their life, that pressure continued to mount. Every moment on the toilet not spent typing out chirpy, encouraging messages felt like abandoning my post. I thought that if I got hit by a car and sustained a traumatic brain injury or died, then at last I couldn’t be faulted for leaving people behind.

But I believe now that it is impossible for a book to save a life. It is the reader, who makes meaning from the book and applies it to their own actions, who does that. I never had the power to do anything except what I was already doing: writing compulsively about whatever interested me.

I write because I have to, and because when I don’t do it, I get insane in less enjoyable ways. This work was always selfish, but I don’t say that to deride it. I mean that no matter how much I dressed it up and worried needlessly about what it might mean, or how it might be received, no matter how much I marketed it and strategized around it and tried to become a living symbol of what it was, writing was one of the only honest expressions of me.

And it will remain that way, long after the audiences have been alienated and the investors aren’t interested and nobody knows who I am. I’ll keep shedding these parts of me, lurking in the grasses with all the other creatures where I belong.

This is so real. Just today I wrote in a semi-public space about the pressures of a public professionalism. Being consumed is exhausting. Being consumed in the imagined effigies of other people's projections is just .weird. And I'm not even famous.

Dude that hookup story is my fucking nightmare!! I honestly got paranoid as hell over the last couple years and had to disappear from social media entirely.

Parasociality is extremely horrifying and also feels unavoidable to me, idk how to deal with it.

I would 100% read your influencer serial killer novel, a bunch of horror movies have come out in that niche recently and I’ve been following along. have you seen Sissy and Spree? They’re my faves in that subgenre, maybe you would like.