Hypermobile Me

Lessons one year after a life-changing injury & diagnosis.

One year ago, my hand and my life kinda fell apart.

The Trump administration was taking office for the second time, and all the trans, queer, diasporic, and disabled people in my life (which makes up essentially everyone in my life) were panicking. Though I’d tried for a long time to be a source of sober political analysis and actionable take-aways, I was panicking too.

I saw access to gender-affirming care being cut off for minors and trans people with mental illness, immigrants and refugees being driven from their only homes, essential resources being cut off, visions of my friends starving and dying. I felt crushed under their despair, but obligated to be strong, and after years of recommending that others find modest ways to make a local difference and keep their minds clear, I lacked the will to do it myself, or any faith that it would make a difference.

I had a new book coming out just a few months in the future, and the obligation to promote it was sour in my mouth. Rolling out my previous book in the middle of the Palestinian genocide had already made me feel disgusted with myself, and I’d turned down or alienated almost every media opportunity. Slinging books struck me as an unacceptable act of self-centering, and it felt pointless for me to be passing out advice on how Autistics could build better homes, sex lives, and retirement plans during an incipient massacre. But I was still contractually and socially bound to do it, my publisher sending me conference invitations, my friends asking me what I would publish next.

I was also taking care of my body in my typical bad ways, attempting to pressurize all my stress by sleeping with my shoulders pressed into my ears and my hands curled up under the full weight of my body. I lifted weights aggressively every morning, no matter how much my wrists hurt. I typed away at random drafts and snippets for hours every day, to prove to myself that I was still a writer, and there was something I could do, even when I felt powerless.

I kept going. That was the thing people always said about me. Four books in five years. A PhD at age twenty-five. A full-time job and uncountable side-hustles. So much to do and say.

And then, all at once, it had to stop.

On January 9th of 2025, I woke up with an inflamed-feeling hand that stung during my morning chest exercises, but I pushed through the pain and went about my usual day. The discomfort and swelling grew into a prickly heat, and by January 12th, I had a giant, hot goo-filled glove at the end of my wrist that sent me running to the emergency room at four in the morning. I was unable to bend my thumb or index and middle finger for weeks.

A barrage of emergency room visits, x-rays, MRIs, steroid treatments, antibiotic treatments, autoimmune condition tests, casts & wrist splint applications, scheduled-then-aborted emergency surgeries, orthopedist visits, and hand therapy sessions ensued. A variety of specialists & surgeons threw themselves at the mystery of my hand, intrigued by the challenge and palpably concerned for me.

In Hand

If you’ve been following me on social media, you might be aware of the complicated and painful medical mystery I have been living out for the last couple of weeks. But for the sake of getting the narrative down, titillating all of my readers who have a keen interest in the workings and failings of the body, and providing an update…

(You can read a full breakdown of my Hand Saga here, and see pictures on this Instagram highlight).

Eventually, my team figured out that I had ruptured my FPL tendon, which connects the muscles of the forearm to the thumb, and the injury had somehow become infected and filled with fluid, blocking the rest of my hand from working for a while. There wasn’t any single cause that anyone could pinpoint, but when one of my emergency surgeons diagnosed me as just about as hypermobile as a human being can be (“Holy shit!” was his reaction to my Beighton Score results), everybody agreed that casual abuse of my freakishly bendy body was probably a major factor.

The hand got better on its own. I just had to heed its insistent uselessness and wait. Then, once I could turn a key or wash a dish, both my hands demanded that I get better at listening to them. If I held my phone for too long in bed, I’d notice an ominous, tweaking kind of pain in my right wrist. Push-ups were no longer an option. When I switched to running, I would sometimes feel a wobbling pain in my ankles or knees, which told me that I had to stop. I started rearranging my workspace, then my life, which inspired a pretty dramatic shift in how I see myself.

Since my diagnosis, I have learned a lot about the needs of my hypermobile body, and the state of the science on mine and related conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (I currently do not believe I have EDS). I know that a great many people discovered their own hypermobility/hEDS through reading my last piece on the subject, and were able to use the comment section to trade a ton of resources.

I thought I’d pass on some of the lessons of my first year as an aware hypermobile person, and some of the lessons, accessibility tools, and life hacks that have kept me from injuring myself again, and sometimes even helped me thrive:

A person can be hypermobile in one joint, some joints, or all the major joints of their body. I happen to be hypermobile as fuck in every joint observed, but some people are only able to hyper-extend their elbows, or one finger. The more hypermobility your body exhibits, the more likely you are to face complications from it, but everyone with the trait should be cognizant of how it can alter their stride, posture, form during exercises, muscle activation, etc. Hypermobility is also strongly correlated with Autism, ADHD, EDS, gastrointestinal disorders, and other conditions, but can also exist on its own.

The world is not built for us! Hypermobility is rarely taken into account by medical providers or physical therapists. There is still relatively little medical awareness of and research into the needs of hypermobile individuals, so doctors are unlikely to detect it and may not know how it affects the entire body system. Many are downright hostile to self-diagnosis, or view hypermobile patients at hypochondriacal or difficult.

If you are hypermobile, then run-of-the-mill physical therapy programs can often cause injury by pushing you into too much extreme activity with too little focus on form! As we will discuss later, gentle, gradual, properly-formed movement with lots of core activation and additional supports (such as braces) are key for healthy movement in hypermobile individuals. Unfortunately, most PT programs assume that increasing mobility and flexibility is useful, when the exact opposite is the case for us. So if you get injured as a hypermobile person, do not just march yourself over to your local Athletico — you have to find a hypermobility-competent provider.

Hypermobility is far more common than people realize! Though it is an understudied phenomenon with low medical provider awareness, hypermobility is actually present in between 10 and 30 percent of the population! Think of all the kids you knew in school who were double-jointed: that’s hypermobility! Not everyone with hypermobility has severe problems caused by their bendy tendencies, nor are they necessarily hypermobile everywhere or afflicted with something like EDS — but we all differ from the norm the medical model assumes comes standard with a body, which means we get worse care.

Our bodies effortlessly do freaky things that can cause injury! This is the most obvious revelation of a new hypermobility diagnosis, but I keep making it over and over and in new ways. The hand, it turns out, is not meant to fold fully 80 degrees backward at the slightest pressure! It feels completely natural for my entire hand to fall completely backward, but that’s a hyper-extension that can cause serious injury! The neck, in fact, is not supposed to bend into a backwards U-shape when you’re eating ass!

Some of my muscles are seriously under-developed and others have overgrown in order to compensate for it. It is common for hypermobile people to lift their arms by tensing our trapezius muscles, aka the nefarious stingray in the back, rather than using the deltoids. This is because we lack sufficient stability in our shoulder joints, and the muscles surrounding the area tense up in order to hold our bodies together.

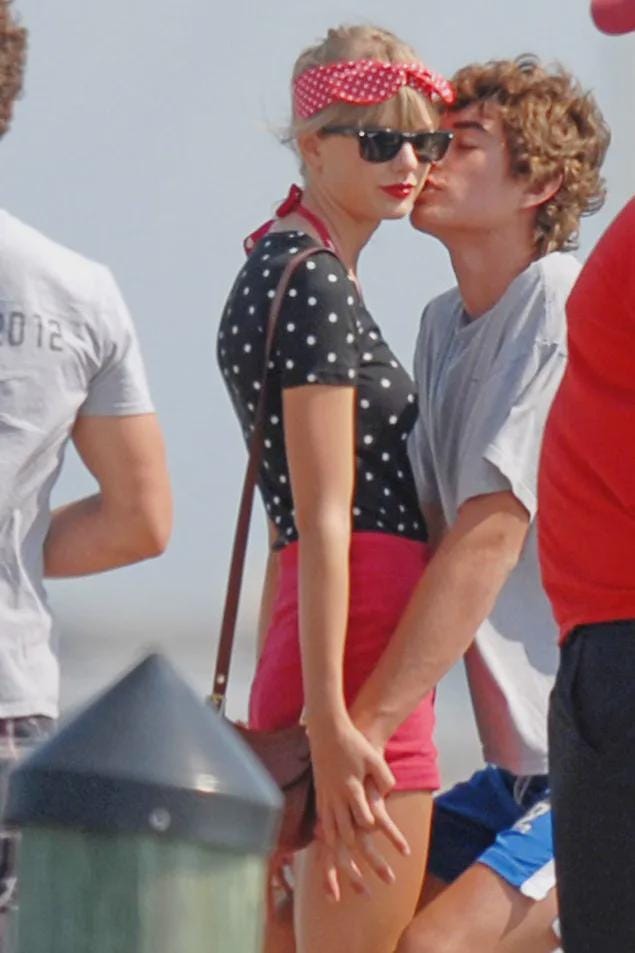

There are dozens of odd compensatory muscle developments like this that happen for us; for example, many hypermobile people have an anterior pelvic tilt because we don’t have enough raw core strength to hold up our disconnected-feeling, swaying spines. Here is an image of Taylor Swift with the tell-tale signs of having a spine that cannot hold itself upright:

Because hypermobile people have less physical stability and a greater range of motion at our joints than other people do, we have to put care into developing our core and stabilizing muscles. Focusing on the abs, lower back, quads, deltoids, and triceps (which play a bigger role in posture than I ever knew!) are key.

At the same time, it’s important to not over-exercise or strain our joints with too much repetitive movement or weight. Intensive strength training is really dicey for us, particularly anything that puts a ton of stress on the knees (like powerlifting), or in my case, the wrists (like push-ups and chest-presses).

It’s generally best to focus on forms of exercise that are less showy and punishing: Pilates and slow, careful movement like Tai Chi come highly recommended in the hypermobile community. They build strength in those essential core muscles that help hold the body up and help carry it around safely, and they emphasize positioning the body into a correct, safe posture, which does not come naturally to us. I really have to watch how other people move their bodies & emulate that if I want to avoid injury, because what I can do with my joints naturally just isn’t what the rest of my body has evolved to do.

Yoga and stretching can be risky for us. I’m still having a hard time accepting this one, because as a physically weak, uncoordinated person who felt immense shame at being placed in special education gym as a child, flexibility and mobility were some of the only areas where I ever shined. When I bend forward and touch my nose to the ground with my legs splayed out wide in front of me, I can make far fitter, more dedicated athletes gasp. It used to feel fucking incredible to roll up to the nude men’s yoga class and effortlessly stunt on everybody with zero practice.

But when we push our bodies into an extreme stretch, we increase the chances of tearing or rupturing a tendon, just as I did with my hand. Even worse, our bodies actually tense up when we extend ourselves too far, and so for us, stretching can actually have the paradoxical effect of making tightness and discomfort worse. Here’s a video explaining why flexibility exercises can do us so much damage — and what to do instead:

I have to stop doing those cute little “double jointed” party tricks. I used to think it was so fucking cool that I could bring the back my thumb all the way down to the front of my forearm and press them against one another. But showing off this freaky feature of my body probably contributed to my hand injury! The orthopedist who diagnosed me as hypermobile cautioned me to never show off any of my body’s more extreme capabilities ever again, and my hand therapist told me that I should be aiming to have far less range of motion. So: no more showing off that I can touch every single part of my back with a flat palm, or hyper-extending my elbows into a convex curve. It may look gross and fun, but it causes damage.

Moving almost always feels better than standing still. My hypermobility has provided yet another explanation behind my being an eloping, fidgety exercise bulimic for all my life! Because hypermobile people feel weak and unsupported in our ankles knees, hips, spines, shoulders, and necks, we find it uncomfortable to stand or sit in place. Other people are able to passively activate enough muscle support to keep themselves standing strong (but not painfully rigid); we wind up wiggling and jostling around, leaning against surfaces, or clenching our bodies when we have to stay in place.

But it’s a lot easier for us to utilize the muscles our bodies need for support when we are moving: walking, shifting weight from one foot to the other, bouncing on tiptoes, and rocking in place can feel a lot more secure than staying still. It’s also generally pretty therapeutic for us to switch sitting or standing positions many times throughout the day. If you’re hypermobile, having a single workstation is probably not gonna be a good fit: most people on the hypermobility subreddit report switching between multiple positions, alternating between chairs and an exercise ball, curling up at a floor desk, and laying supine on a couch with their work in their lap.

A diversity of gentle exercises is essential. Movement is good and strengthening exercises are beneficial, but it is very, very easy for us hypermobile people to take things too far. After years of devoted strength training, my hand injury provoked me to get into gentle flow exercises, then to take up running and biking.

Most people in the community (and most hypermobile-competent care providers) would caution against running: it shoots a lot of force right into some of the body’s most vulnerable joints, such as the knees. But I have strong legs and a lot of anxious demons to outrun, and I’ve found that working more cardio into my repertoire is helping me learn how to breathe correctly (because, as it turns out, I have also been holding my breath and failing to engage my diaphragm for all my life! This is also a common consequence of hypermobility and Autism!). I also feel a powerful need to exercise that is pretty hard to reason with. So for me, rotating between dumbbell, kettle bell, resistance band, and cardio exercises allows me to burn off stress while still listening to the little tweaks and pains of my body.

Any kind of repetitive movement or pressure can cause injury. This summer, I had the opportunity to walk in the Chicago Pride Parade with a local puppy play group, and I happily donned my mask and waved my paws at strangers. Immediately after the parade, I felt a straining sensation in my wrists, and I was in too much pain to write emails or type on my phone at all the next day. I had to take an entire week off from writing — all because I spent two hours waving nonstop.

Now that I know what the precursor to a tendon injury feels like, I notice all kinds of activities that cause strain. If I spend too much time flicking pokeballs in Pokemon Go without a break, I can injure my thumb. If I have a lot of sex that involves putting my ankles behind my head, I can feel my knees shifting apart. Opening jars, carrying boxes, bending too far forward or backward, anything extreme can hurt me if I don’t pay attention to that stretchy, achey feeling in my joints and seek out rest and physical support.

Braces, compression wraps, and elastic bands are a godsend. When my knee started to feel like it was separating due to too much running and leg-bendy sex, I started wearing a knee brace throughout my day, and stopped using my standing desk for a while. The gentle pressure the brace put on the joint felt amazing, and it was suddenly far easier for me to walk in a smooth, controlled way. I was so used to my body jolting and popping that I hadn’t realized it wasn’t supposed to be exhausting and painful to walk. I thought, is this what having typical mobility is like?? It turns out that it is.

I have also gotten into the habit of using ace bandages on my wrists when I lift weights, and sometimes wrapping my ankles before running — though I should do it more often. I find that slipping on an elastic brace with a velcro or hook closure is a lot easier than taking the time to bandage my body, and it stays in place better, so I can enjoy stabilization all day. I also really like wearing an elastic hip band around my hips, even when I am not exercising; it gives me a gentle pressure that makes sitting or lifting things far more comfortable.

There are also custom accessibility tools designed to support hypermobile people, such as the Body Braid, which I’m really hoping to try out at some point. It looks like an absolute feast of positive sensory input and supportive pressure:

I finally understand a lot of my pressure- and stability-seeking behaviors. Before I knew I was hypermobile, I assumed my tendency to sit with my knees pressed to my chest was purely an Autistic search for stimulation. I also tend to cross my arms, hold my own hands up by the wrists, throw my legs over chair arms, prop my lower body up against a wall with my head tilted downward, cross my legs, and lean against things. This once got me evaluated as ‘too casual’ and ‘cocky’ during a job interview.

Now I understand that I’m not only a disrespectful and pressure-loving freak, though I certainly am those things too. I also have a body that takes way more energy to hold up than most, so I instinctively find support wherever I can get it. That is a beautiful thing! I am happy that my body has done what it needed to be more comfortable! Instead of being ashamed of my weird posture or my supposed physical ‘weakness,’ I can see now that simply existing in my body is a more demanding task than most people can understand. This means I need more rest and more help.

Our bodies can relax ‘too much’! Another fun paradoxical effect of hypermobility is our tendency to physically collapse in on ourselves when resting, causing our joints to inappropriately sag in the wrong direction. We also can become too limp and still when chilling out on the couch (in my case, this is especially heightened when I’m high), which means we get muscle discomfort.

Did you know that the average person ‘should’ be activating their core and back muscles a bit while they sleep, and that it’s normal to shift your weight an almost imperceptible amount even during relaxation?? I didn’t. I just fall into a heap of bones, and rely upon the couch or mattress to ground me, the way a cat does when it’s curled up. But that shit can hurt. To keep their sagging joints lifted and support the weight of their heads or bodies, many hypermobile people sleep in a nest of Squishmallow-type stuffed toys, or use a pregnancy pillow:

Learning how to sleep on my back with proper neck support has dramatically reduced my back pain and improved posture. All my life, I have slept in a painful, face-down, curled up position, with one leg thrown out and bent to ground my slipping hips, and my arms folded underneath me (often with my wrists bent inward, hence my injury). At rest, I have looked more like an oddity at an archeological site than a living human:

This sleeping posture filled my trapezius muscles with thick knots, kept my shoulders permanently tensed and risen, and hurt basically every joint that I had curled inward. But getting myself out of the habit of sleeping this way felt absolutely impossible, because my body craved so much pressure. I even slept face-down like this right after top surgery, when the front of my body was stitched together and filled with tubes!

The game changer, for me, was a recent stay in my sister’s guest room, which her Autistic girlfriend had styled up into the perfect cozy age-regression chamber: a high-walled couch with firm foam stuffing, emotionally soothing fairy lights and toys on display, fuzzy but substantially weighted fleece blankets, and a huge pile of stuffed animals I could prop my head on and surround my body with.

In this set-up, I was able to sleep on my back, with just a thin Squishmallow supporting my head and neck, and my arms relaxed at my sides, with my shoulders down and as far away from my ears as possible. The weight of the blankets on top of me provided the front of my body with the pressure I was used to getting from pushing my face into the mattress. The stuffed animals all around me gave me the sensation of being contained, so when I really wanted to curl up and sleep on my side, I could just ‘trick’ myself by burying my face into one of their fluffy bodies.

It has been fucking fantastic. Every single night that I have slept like this I have felt completely relaxed and supported, woken up with zero back pain, and have been able to go about my day with none of the usual shoulder tension. And I found the set-up really easy to replicate at home with my own beloved Pokemon stuffies.

Fixing my posture is very important, I’ve learned. Figuring out my hypermobility has meant waging war on every little thoughtless bodily habit that causes me untold tension and pain. I have always kept my arms really high up and curled up against my body, in a little squirrelly position. This looks adorable and gay and feels secure, but it pulls my shoulders forward and up, causing back & neck problems while worsening my posture.

One really easy hack that I’ve recently discovered is that I can force my arms and shoulders down into a correct posture by jamming my hands into my pants pockets! Coat pockets are too high up, and cause me to bend my arms forward at the elbows and scrunch my neck forward. But pants pockets are lower, and require me to elongate my arms! The pressure of the jean fabric also keeps my arms in place, as swaying them when I walk often feels too uncomfortable.

I also recently took the arms off my desk chair: trying to rest my arms on them caused my whole upper body to tense up and made my workday massively uncomfortable. I’m having to take away every opportunity to hunch: no more leaning forward on tables, no more sitting in shitty chairs with a lack of lower back support. If I feel myself folding forward into The Gargoyle (tm), I engage my ass muscles, curl my tailbone inward and down, drop my shoulders, and take a deep breath into a gentle raising of my chest. It’s sometimes too exhausting for me to do, in which case I search out good sources of support and stabilization instead of collapsing.

My workflow & productivity have changed a ton in response to my disability. I use a sideways mouse, because it’s easier on my wrist. My desk is covered in L-shaped foam so I have support when I’m typing. I switch between a seated and standing position at my desk throughout the day. I cannot type as much as I used to, so I use voice-to-text apps. (Basically any social media post or text message that I send is composed using my voice, these days).

But even with all these changes, I’ve had to accept that my productive capacity is not what it once was. It is not comfortable for me to sit at a desk for more than few hours, or to sit still for very long at all. I cannot withstand much political or social stress. During the months that my hand didn’t work, I was away from my home office the majority of my days, riding busses to medical campuses and wandering through Hyde Park in between appointments.

I found all this time away from The Dissociation Machine and all my petty life problems to be quite meditative, and as I started recovering, I would ‘assign’ myself long walks on the lakeshore path or find a bunch of random errands to run so that I could not be pulled back into overwork again. I started cultivating new hobbies, like singing, which did not require sitting at a computer or using my hands at all. I started playing a mobile video game, Pokemon Go, that required I get out of the house, and which gave me an app to play with that couldn’t cause doomscrolling.

My injury also emphasized to me the importance of receiving care, something I had always shied away from. Unlike most hypermobile patients, I was incredibly privileged to get a diagnosis almost right away, and to be surrounded by curious, highly involved medical providers the entire time. From the moment I reported to the University of Chicago’s orthopedics team, I was listened to, and my case was carefully studied. My providers did additional research on injuries like mine, possible effects of the testosterone I was taking on the FPL tendon, and sought out support from colleagues when my test results were unusual. The nursing staff at U of Chicago were especially warm and chatty with me, as were so many of the patients.

Though I was facing the loss of a body part that is essential to my creative life and career, I never really felt all that despairing at any of it, because I found learning about the mechanics of my body absolutely fascinating and I was gaining so much meaningful contact with other people.

The winter that led up to my injury had been a dour one that saw me spending most days banging away at my computer without much human contact, and flitting between upsetting headlines, then laying out in an anxious, stoned mess on my bed all night, unable to relax. But as soon as I got injured I was working less, speaking to a ton of fascinating, skillful people who were interested in me, traveling every day all across my city, and spending my time cultivating my voice instead of languishing in my head.

When this all first started happening, somebody told me that the left hand represented ‘self care’ in a variety of spiritual traditions, and encouraged me to see the injury as an opportunity to get more in touch with myself. I scoffed at it, but soon their statement proved to be true. I’d been putting too much pressure on myself psychologically and physically for a very long time, and at last stopping had become non-negotiable.

I had a lot of my identity wrapped up in my ability to produce content, to sculpt my body into a masculine V, to carry everything on my own. But suddenly my life was no longer a thing I could grip so firmly, and I had to welcome it being cradled by others, and recognize the necessity of it being handled lightly by me. Every single time I catch my blood pressure rising, hear a shaming voice telling me that I should be doing more, or notice that familiar twinging in my wrist, I stop what I am doing. I have no choice but to commit myself to less pain, to throw away the martyrdom of suffering just for the sake of it, and set about the tedious, unending process of caring for my body as a living thing.

I am sensitive and flexible to the pressures of my environment, sometimes excessively so. Where others can stand firm, I sway in the winds of life, like the tendrils of a budding tree. And it’s lovely to know now that this is how I function, and to see it in the funny wave forms of my stride, or the way a similarly-wobbly loved one throws their thigh over my body in a search of a grounding I can’t provide to myself, but can give to them. How wonderful to know how we need each other. How freeing it is to join together in falling apart.

Devon, you have to stop doing this, dropping things in my inbox that make me go "oh. of fucking course this isn't me being Uniquely Weird". I had forgotten that the signs of hypermobility I exhibit are, in fact, Signs. There's knowing something, and there's *Knowing* it, and sometimes you need the reminder that needing to lie in bed in a way that makes the Yamcha pose look comfy to sleep is fucking weird.

Still knowing it so you can take care of yourself better, no matter how confronting that might be, is the only way to go forward. I used to be quite the obsessive weightlifter (not least because I tried to get those pesky trans thoughts to go away, which uhh, didn't work), really disliking the more gentle, less heavy ways of moving myself. I recently had the privilege of going on a trip to visit some family, and while there, I out of nowhere got in the habit of just taking walks. Befuddled the hell out of me, I always *hated* walking, it felt so unpleasant. But as I realized then, it wasn't just the novelty of a different place, it was the fact these walks were on dirt or gravel paths, full of fallen, crunchy autumn leaves. Instead of hard, unyielding pavement and concrete. It's very tangential to the above, but I'd figure I'd share something that helped me.

The things you publish and share feel so often like they were custom-fit for my most frustrating blindspots in my own wellbeing as a queer autistic person, and I'm really grateful that you take the time and effort to synthesize and publicize your life experience, because reading your work has given me a first-time feeling in my life: that someone is ahead of me on the path, and I'm not alone. I so appreciate you and your candor and what you do. Thank you.