My Transgender Year Without Tits

Scar care, shirtlessness, posture improvements, buoyancy changes, and more!

Happy Pride Month!

On June 1st, 2023, I underwent a double-incision bilateral mastectomy with no nipple grafts, performed by Dr. Lawrence Iteld in Chicago. I wrote previously about the process of selecting a surgeon and my pre-operative experience here, and the first few week of recovery (which I found to be shockingly simple and painless!) here.

When this essay drops, I will have spent my first full year without tits! (And nipples!) I’ve been free of surgical drains and dressings for over eleven months, and, after a couple months of consistent silicon tape applications, I have been walking around with my scars proudly bared consistently. In the past several weeks, I’ve even started taking my bare chest to the tanning salon, without placing any protective covering over the scars.

(My surgeon would probably yell at me for that, but hey, he also said that “men of our age should be wearing tons of sunscreen everywhere,” and that’s a tip I can abide by.)

So how has the last year been? Have I built up pectoral muscle to replace my incinerated jugs? How long did it take me to recoup any mobility and strength loss I incurred during recovery period? Was I diligent in my scar care, and did it make a lick of difference? Now that I am disabused of my heavy boobs, will I never have problems again?

Let’s briefly review my first few months of healing, and then dive into the overall changes that I’ve noticed in year one — the good, the bad, the neutral, and the unexpected.

The First Few Months of Recovery

When we last left our hero, he was pain-free, enjoying the removal of his surgical drains, and looking forward to the date three weeks after surgery when he would be allowed to stop wearing a tight-fitting binder at all times. I am happy to report that everything went according to plan. Admittedly, I did fudge the aftercare instructions a little, choosing after about a week and a half to wear two tight sports bras over my chest instead of the itchy, blood-stained, clamped surgical binder that kept cutting into my armpits and made me feel disgusting.

It didn’t seem to make any difference. I never developed much swelling, aside from a tiny bubble of puffiness right at the center of my chest where my two scars join together. That disappeared within the first month of recovery, and though the skin covering my chest felt in my mind like detached deli meat that could fly off at any moment, I don’t think the binder was necessary for holding everything together.

My friend Jesse Meadows (the author of Sluggish) got top surgery recently, and their surgeon told them prolonged binding wasn’t necessary. This seems consistent with my own surgeon’s recommendation that I move my arms freely to their full range of motion from the moment I woke up.

Exercise

The post-operative guidelines of the not-so-distant past over-emphasized the incapability and passivity of the patient — think of how wealthy pregnant women in the middle of the 20th century were advised to spend much of their gestational period in bed. The science has advanced significantly since then, and we know that movement is more recuperative than rest, if you can manage it. It’s better to use your arms and get the blood pumping in your chest than it is to let those body parts atrophy. Maintaining activity also makes it easier to bounce back from the effects of anesthesia or any medication you might be on after surgery, both physiologically and psychologically.

All of which is to say: I started lifting weights after just two weeks post-op, even though my surgeon told me to wait a month. Sorry! I’m just such a Chad gym bro pecsmaxxer!! I was not able to rest for a single day after my operation. I had no pain, my endorphins were through the roof, and I was desperate to use my new, beautifully flat-chested body to its fullest.

I don’t regret this decision at all. I started out lifting 10-pound weights instead of my usual 15, spending between twenty minutes and a half hour per day moving through back, arm, shoulder, glute, leg, and core exercises. After about a week or two, I was back to handling my usual weight load, though I held off on chest exercises for a while. I felt strong and capable, especially once I finally had the binder off and could move my body more freely. I was doing push-ups and chest presses again within a month post-op.

Because I never stopped using my arms, I lost no mobility or strength during my recovery. Some trans men complain of tightened muscles and tendons and a scrunched posture following surgery that may require months of physical therapy to address, so I consider this a win. The only (possible) downside to moving my body so freely is that I did develop noticeably thick scars. The reason I suspect there is a connection between my movement and my scarring is that my scarring is far thicker on my right side, which is my dominant side.

For reference, here are my incisions at one month post op, before they’ve properly formed into scars:

And here are my scars at four months:

Scar Care

Now is a good time for an aside about scar care myths and the insecurities that a lot of trans guys bring to bear in their recovery.

On the top surgery subreddits, dudes are absolutely obsessed with minimizing scarring and achieving a cis-passing chest. They absolutely covet the light-colored, pencil-thin scar look, undergoing multiple rounds of steroid injections to reduce any signs of scar elevation and slathering themselves in silicone, vitamin E oil, coconut oil, bio oil, scar strips, Vaseline, and more. They massage their scars with jade rollers, wear rash guards to the beach for multiple years, and avoid moving their bodies for the slightest hope of a fainter scar line— and then they are demoralized by the results, because how a scar develops is determined by a person’s genetics, not their behavior.

It’s important to understand how scarring works and why it happens, so that anyone recovering from a major surgery has realistic expectations, and perhaps a healthy sense of gratitude for all that their body is doing for them when it scars.

A top surgery incision is a long open wound, where two pieces of skin that were previously separated by multiple inches of breast tissue are now suddenly slapped against one another. There’s a ton of space between those two flaps for bacteria to find their way in. During the first few days after surgery, surgical mesh prevents infection from setting in for most patients. But in the long term, the body has to seal up this long, thin hole by itself — and it does so by throwing as much scar tissue as it can, growing long threads in all directions like a pile of pick-up sticks getting dumped on a crack in the sidewalk.

Your body has no way of knowing where the protective threads of scar tissue should start and stop (after all, the nerves in the area have been severed), and it does not care one bit about aesthetics. It is responding to a potentially mortal threat by covering it up as thoroughly as it can. And so scars thicken over the course of healing, reaching their maximum width at somewhere between three and six months after surgery. How those scars look and whether they raise into a keloid formation will depend on the person’s genetics.

Because scar tissue doesn’t “know” where to go, it also grows under the incision and can potentially glue itself to the skin to the muscle and fascia underneath. This is why scar massage is essential to the recovery process: to prevent adhesion of the scar tissue to all the body tissues underneath. Scar massage has a minimal effect on how scars look on the outside. It feels good and helps break apart tissue where it isn’t needed, but that’s primarily under the skin.

One of my surgeon’s assistants taught me how to properly care for my scars three weeks after my operation, using a clear silicone gel. She suggested I rub the scars up and down and in circular patterns, as if I were playing with the seam of a piece of clothing. I was instructed to do this for three minutes at least twice a day, and told I could cover my scars with silicone scar tape all day long to hydrate and shield them if I wanted as well. I did this for a while, but once it got hot out the sweat trapped underneath the scar tape caused a rash, and so I quit using it.

I was very relieved that Dr. Iteld’s office didn’t push any expensive scar recovery creams on me, and only ever showed enthusiasm about the course of my recovery. Because it’s a private plastic surgery office, I had gone in expecting a sales pitch, but thankfully this wasn’t the case. I was happy with the look of my chest, understood that scarring was a gift from a body that was only trying to protect me, and didn’t obsess over the day-by-day changes in my appearance much.

Here’s how my scarring looks now:

There’s not much else to report about the process of healing. My body has essentially settled into what it will be for the next several years, some potential fading (or sun damage) of the scars notwithstanding. Still, the experience of not having tits has exerted quite the dramatic influence on multiple areas of my life. So here’s a round-up of all the changes I have noticed so far:

Posture

I have always had absolutely terrible posture that other people never stop telling me to correct. Some of that is directly linked to my chest dysphoria, as the so-called Supermodel Hunch is famously effective at minimizing breasts. But I also have a family history of scoliosis, reduced muscle tone due to Autism and the early prescription of hormonal birth control, and I tend to tense up to cope with stress and overwhelm. So my shit is all fucked up — though I remain a bit skeptical of the concept of “good” posture, and view it as a bit ableist and neuro-normative.

With my tits cleaved off, I do find it a lot easier to move around — I am unburdened of the DDD’s that used to exhaust my back and drag me down toward the floor. At a house-warming party in early August, a friend remarked at how I was sitting with my back fully pressed against the rear of my chair my arms spread wide behind me. I was taking up a ton of space in a relaxed, masculine posture. I looked at ease to them. That was unusual for me — I am so prone to squatting in my seat with my arms hugging my knees.

Since getting top surgery, I’ve learned that most people’s arms and shoulders naturally move and sway as they walk, instead of remaining bolted in place at their sides. That had never been the case for me before. I find my movements are more fluid now, and my form during workouts is a lot better. I have enough awareness of my torso now that I’m no longer warring with dysphoria that I can quickly make an adjustment.

Still, I do carry my tension in my back and shoulders by reflex. It alters my posture in odd-looking ways, at least by neurotypical standards — enough that a masseuse I met last year was shocked and confused at the shape of my body. Some of this is just a natural physiological quirk I’d like to accept about myself — though people’s invasive comments and unasked-for adjustments make that difficult. I have a forward neck tilt that’s common among Autistics, too, and I refuse to feel bad about that.

I have practiced dropping my shoulders a bit from time to time though, using heavy weights in my hands to help guide them down. It does help relax my back a bit. So does sleeping face-down on the wedge pillow that I bought for my surgical recovery. I move around in all kinds of funny but natural-feeling ways now that no body part cases me acute discomfort, and that’s all been a net benefit. I’m aiming to let my body be fully my own, moving it in the ways that feel good rather than aspiring to a cis, non-disabled presentation.

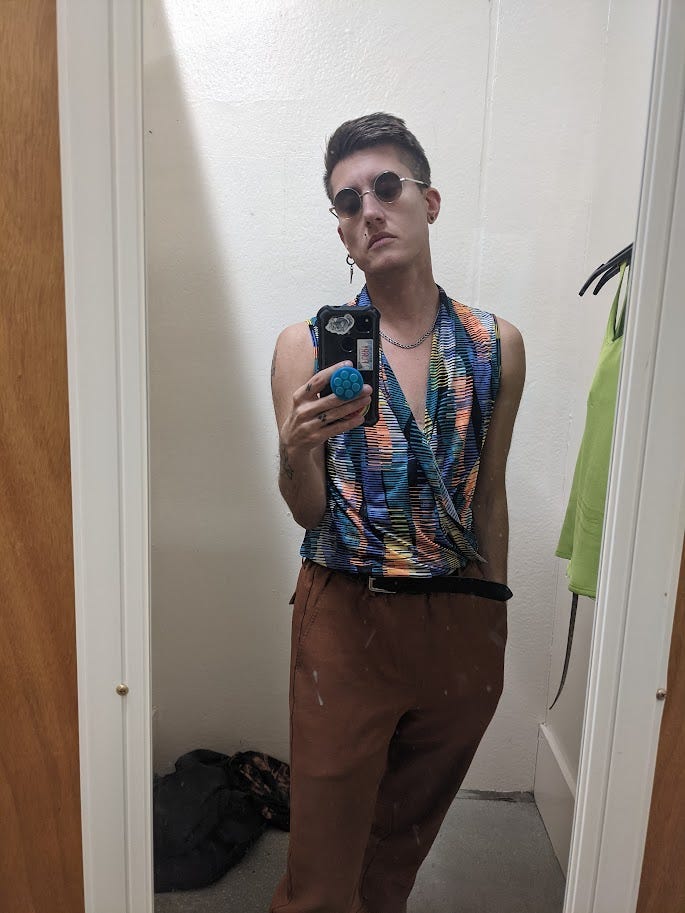

Limitless Clothing Options!!!

Easily my favorite consequence of top surgery is the huge array of clothing options it has afforded me. As a trans guy with tits, I always felt that I needed to conceal my breasts under baggy t-shirts and button-ups that closed all the way at my neck, so that my binder wouldn’t be revealed underneath. As a “girl” my options hadn’t been any better, because my breasts were too large to be contained by anything skimpy or revealing.

For the first months after surgery, I reveled in the simple, unbroken plane of my chest. Shirts sat so differently without several pounds of breast tissue and a tight compression garment underneath. Then, on the first properly warm day of this year, I realized I could return to the women’s section of the store as a completely changed man:

I can wear tiny paper-thin blouses and ultra-cropped crop-tops and dresses with deeply cut V-necks! I can wear a jean vest over my bare chest with nothing else on it! I can go running and swimming without a shirt on at all!

The removal of my breasts has freed up entire worlds of gender expression for me that did not feel accessible before. I’ve been dressing more femininely and in more revealing clothing throughout this year, no longer having to offset my supposedly “feminine” curves with boxier, bulkier shapes.

I used to hate showing cleavage, even before I transitioned, it made me feel too vulnerable to attention and harassment — but now I want to flash my scars at everybody. I’ve also returned to wearing hip-hugging skirts and bike shorts from time to time, because I love how the widest part of me juts inward to meet my narrow top half.

I can’t believe how light and airy I feel in my upper body now — it’s easy to dance with my arms floating all around me, shimmying my chest with pride the way women who actually like their breasts do. I also can’t stop referring to my flat chest as ‘my titties’ — I feel a pride in what I have and a satisfaction with the money well spent that reminds me of my friends who have gotten breast augmentations. Finally I have the delicate fairylike body of my dreams — and I can dress it however I wish.

Chest Sensation

The skin on my chest remains quite numb one-year out. This isn’t unusual: nerves can take multiple years to regrow, and full sensation does not always return. Some people find the deadened, uncanny sensation of post-surgical nerve damage painful or disturbing, but I don’t mind it. I should note that I’m pretty insensitive to pain generally.

In the last month, I’ve finally started to experience some sporadic itching around my scars that can’t be satisfied no matter how hard I scratch. I assume this means that other sensations will be returning to the area in time, too. For now I just rub and pound at my incision line whenever the itching comes up, though it doesn’t help much.

Since I didn’t elect to get nipple grafts, my body’s nipple sensation is growing back pretty much wherever it likes. (This can sometimes happen for top surgery recipients who do get nipples anyway — sometimes the nerves find their way home, sometimes they wander off to the side). I can pinch a cluster of skin on the sides of my chest and feel heightened sensitivity there. It’s a bit like the way my nipples used to feel when crushed under the weight of the binder. The pain of pinching my ghost-nips is somewhat pleasant, but also strange. I’ve never had strong feelings about nipples one way or the other, so I’m fine with this result.

Muscle sensation has completely returned at this point — in fact, without the distraction of breasts, I am far more attuned to the exertions of my pectorals. I can intentionally activate those muscles when lifting now, and feel them building up as I’ve continued strength training. It’s fucking cool to be able to do lots of push-ups now, and to massage muscles of my chest.

My hand roams all over my chest these days as a stim and self-grounding method. I’d never felt that it was “appropriate” to touch my chest in public before, and now my body is completely my own to explore. Feeling the thrumming of my heart and the ripples of my ribs beneath my skin is a sensual experience for me.

Body Hair Growth

Ever since my scars started forming, I’ve noticed a steady line of dark body hair marching its way across the center of my chest, charting a path along the scars that leads from armpit to armpit. I’d been told by other trans mascs to expect this — the body tends to send hair to the injured area, perhaps as a form of protection? — and it really is noticeable. It looks a little bit funny, so I’ve mostly chosen to keep it shaved. But there are other changes happening throughout my body that might eventually even out the hair coverage:

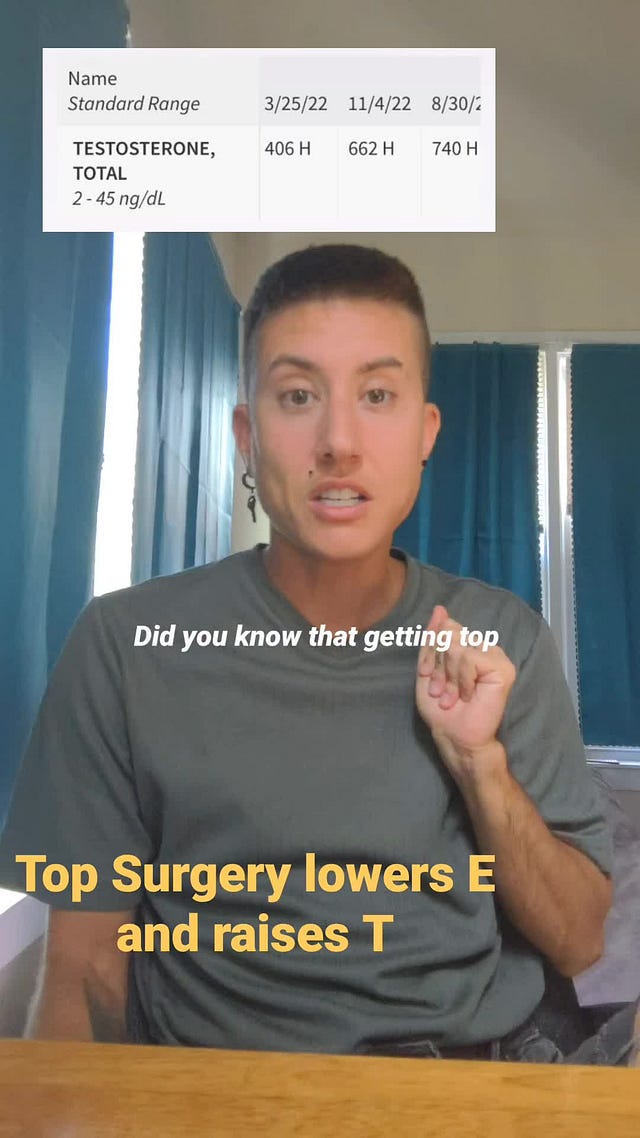

Testosterone Elevation

Since top surgery, my testosterone levels have naturally gone up! This is an effect of complete breast removal that many trans people (especially ones who are not on hormones) might not know to expect. But it’s one that many recipients of mastectomies do in fact notice! In my case, T levels went up by nearly 80 ng/dl:

The reasons for this are fairly straightforward. The breasts don’t just contain fat, they include milk ducts, lobules, and other tissues implicated in the body’s hormonal system. As one friend put it to me, “there’s estrogen hiding in those things” — and consequently, the full removal of breasts can sometimes cause T levels to spike.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

I noticed the effects of this change pretty quickly. My muscle development increased, as did the hair growth on my face, back, and upper chest. I began experiencing slight vaginal dryness for the first time ever in my life, and some cramping during orgasm (which can signal vaginal atrophy). My energy levels shot up, and my face looked slightly more masculinized.

I ended up reducing my hormone dose to balance out some of these effects. However, trans guys who are looking for a hyper-masc presentation might welcome these changes, and the more challenging side-effects like atrophy can also be mitigated using vaginal estrogen creams. Some nonbinary people who are not hormonally transitioning might welcome the news that top surgery alone can cause a modest, low-dose-T boost. Others might not desire hormonal masculinization, and should take note of this potential effect. On the whole, though, it is quite subtle.

Higher Energy and Mood

My mood was noticeably elevated as a result of my surgery. I felt less dissociated from reality, and as if I had more agency in controlling my own life. I socialized a lot, could party all night, and made a series of bold decisions I’d been anxiously contemplating for years: I tried psychedelic mushrooms for the first time, invested some of my savings in new ways, and aggressively pitched an ambitious new book.

People close to me said that I seemed more confident and together. For a while I felt tougher and more masculine, too — as if I could stoically shoulder life’s burdens without folding for once. Eventually this settled itself out, as no positive changes in life seem new and shiny for long. Still, my new baseline is significantly higher than it once was. I went from fighting my way upstream to flowing with the tide.

And speaking of water…

Swimming

As an uncoordinated, underdeveloped child who was enrolled in Special Ed gym, swimming had been my one physical solace. Every summer I happily wasted away the hours at my local pool, undulating below the water pretending I was a dolphin or a mermaid. Swimming was the one sport that in which I could keep pace with my non-disabled classmates, sometimes even lapping some of the more athletic boys in my class. As a teenager I became a lifeguard, because I so naturally understood moving within the water.

I looked forward to getting to swim with a bare chest following my top surgery. And so my family and I scheduled a trip down to Miami one month after my operation.

Thankfully, I was feeling completely normal and totally recovered by the time we got down to Miami, and so I got to spend my days traipsing all over the South Beach area and swimming in the ocean and the pool. Every time I slipped my shirt off to plunge into the water, I felt exposed in a naughty and liberating way, as if I were getting away with something. Some trans people who opt to go nipple-free report feeling self-conscious exposing their unusual chests in public, but I didn’t care about drawing stares. I was thrilled to feel nothing separating my body from the warm Atlantic.

It was then that I noticed a side-effect of top surgery that no one had warned me about: It is now a lot harder to swim. I’ve been going around with two jumbo-sized flotation devices strapped to my chest for the past twenty years or so, and without them, it’s incredibly difficult to stay afloat. So much for all my years of being a strong swimmer!

It turns out I’d been relying on my body’s relatively high body fat percentage to make swimming easier all that time. Now that my body’s mostly muscle (thanks to T and weight lifting) and has no breast tissue, I sink. I used to love just treading water and soaking up the sun for hours. Now it’s exhausting.

I can imagine this effect would be quite the dismaying surprise to trans masculine people who are competitive swimmers, or to anyone thin who doesn’t have additional fat stores to help them bob on the surface. So please, be aware: as delightful as swimming with a bare, flat chest feels, it does come with a performance cost!

Now let’s discuss one additional post-operative effect I’m a bit ambivalent about:

Eating Disordered Ideation & Behavior

I’ve lived with an eating disorder since my early adolescence, though transitioning has done a lot to help mend it.

I believe firmly in fat liberation and try to practice neutrality regarding my own body. I eat somewhat intuitively, and avoid upsetting information like my own body weight or calorie counts. I also see numerous benefits to adopting a harm reductionist approach to disordered behaviors such as restriction and excessive exercise: recovery is not binary, and actions that fulfill my psychological or sensory needs are not all bad, they simply come with their own risks and benefits that I can make careful decisions about.

In all of these respects, top surgery has been both a balm and a trigger. Before surgery, I lifted weights religiously to maintain a masculine-looking physique. If I missed a single day of shoulder or chest work, I feared I’d become soft and “womanly” again. I was also terrified of missing even a single dose of T. My greatest fear was that my breasts would look more prominent or balloon in size.

Since getting top surgery, I have none of those fears. I lift weights because it’s improved my body’s functionality and it gives me a satisfying endorphin rush, but if I miss a couple of days, it’s not a big deal. Sometimes I prefer to take a long walk or work through a stretching routine instead because that’s what my body needs.

However, top surgery has also made me acutely aware of the smallness of my chest and waist, and allowed seductive thoughts of shrinking myself further to creep in. I used to frequent pro-anorexia Livejournal blogs as a teen, viewing “thinspiration” photos of bony bodies and longing for the supposedly androgynous appearance of waifs and sickly-looking male characters like 2D from Gorillaz. In the years since embracing recovery, I’d given up any thought of ever resembling those figures. My body was what it was, and any body size or shape could be androgynous if the person identified that way.

Suddenly though, top surgery had made my body resemble those of the people I’d once envied. And some long-dormant part of me whispered that I should pursue my old goals.

Top surgery changes the holistic appearance of the body, and for some people that means an increased awareness of one’s hips, stomach, ass, thighs, or other curvy parts. Multiple trans guys have privately told me that before top surgery, they perceived their breasts as their primary “feminine” body part, and the only one that caused them major dysphoria. After surgery, their dissatisfaction sometimes migrated to whatever part now seemed the most “womanly” to them.

And there are some trans guys on the top surgery recovery forums who complain of still viewing their (totally flat) chests as too “full” or “buxom,” or insist that their surgeon must have left some tissue behind, no matter how many of us reassure them that they have clearly have completely flat chests.

Dysphoria is the trauma of living in a body that’s been forcibly gendered by the outside world. We can alter our bodies to align better with our self-images, to express ourselves, and to help other people more accurately see us, but it’s not realistic to expect a lifetime of gendered trauma to dissipate in one day. Transition is a means of taking control over bodies that haven’t always felt like our own. And it’s that repeated assertion of self-control and self-authorship that heals us, not any specific aesthetic results.

I’ve written before about how pursuing gender affirmation can create a paradoxical hyper-awareness of everything about your appearance that you don’t like. It doesn’t mean that gender transition isn’t for you. It’s merely a growing pain, the sting of ripping a festering Band-Aid off. And while it’s worthwhile, it also sucks, and requires a boatload of coping tools and a strong support system in order to endure.

So if you’re contemplating top surgery, do keep in mind that it could set off a chain-reaction of unwanted thoughts about your body. In my case, I’ve been able to stave off my worst eating disordered impulses by sharing lots of meals with loved ones and friends, consuming lots of fat liberatory content, and intentionally reducing my exercise load a bit rather than increasing it. I can also accept that my body and my mind will continue to change, and that there’s nothing wrong with having the occasional upsetting thought.

Adaptation

According to the theory of Hedonic Adaptation, most people’s overall life satisfaction returns to its original baseline about one year after any major disruption. Whether you get married, adopt a child, win the lottery, lose a loved one, or go bankrupt, the general trend of your happiness is for it to return to its usual mean.

I’ve found that to be the case with adjusting to life following top surgery, too — all the highs, lows, and surprises eventually settle into the background of life. In a matter of months I could no longer remember how having triple DDD’s felt, how I ever could have tolerated them. The body I’d longed and labored and pinched pennies so desperately for was now just the default to which I felt entitled.

I was elated by the results of my surgery at first, and unusually confident in my body — and then I became the same anxious person that I’ll likely always be. My newfound lack of dysphoria made me hyper-attuned to my bodily states — then I went back to dissociating in front of the computer, because I’m still a writer with an internet addiction. Losing breast tissue caused a spike in eating disordered thoughts — but I went back to my overnight oats and continued not weighing myself and then I was fine.

I can weather everything that life has thrown at me so far, absorbing new experiences into the whole of myself. Nothing I do will resolve my insecurities or completely quiet the fault-finding voice inside, and that might be for the best since overanalyzing things is how I’ve chosen to spend my life.

Andrea Long Chu wrote in 2018 that her new vagina would not make her happy, and that it was foolishly cissexist for other people to expect that it would. Trans people have the right to alter our bodies because all humans do, and because we want to, and because if we rid ourselves of the worry of gender dysphoria our brains can find more useful things to stress about, like the ongoing genocide or addressing climate change.

The human brain has evolved to survive, not to be easily satisfied or rendered complacent, and that means most of us will forever keep searching for new ways to grow and rooting out new sources of dissatisfaction. I find that a beautiful thing. These days I’m worrying about editing my fourth book, and painting my new apartment, and getting to more student encampments. I’m stupidly fixated on how bad my hair looks as it’s growing out. I’m annoyed by the adorable toddler screaming upstairs and the taxes that fund the tools of war.

I’m glad that I can trouble my mind with all these matters both great and small instead of worrying about the size of my titties. I hope that every trans person gets to find better problems than their dysphoria, too.

If you’re reading this, I hope you have a Pride Season that is filled with activity, and sensation, and experiences both private and communal that help you to really feel your liberation in your bones. Thanks for accompanying me on this yearlong journey, and for bearing with all the selfie spam. It will continue — I’m absolutely in love with my appearance right now, and I will make it everybody’s problem.

there’s a draft in my notes titled “The Cognitive Benefits of Cutting Off Your Tits” 😂😂 I have so much more room in my head now!! it’s so easy to go outside!!! I wore a mesh shirt this weekend!!!!!

as for compression — I literally wore it for 24 hrs, maybe 36 if you count the next few days where I tried to put it back on and kept panicking around 4 hours in lol. I am so glad my surgeon was chill about it bc it was really not possible for me sensory-wise.

I was scared I was gonna get complications (bc everyone on r/topsurgery seems to freak out when someone asks if it’s ok to take their binder off) but I found this review of post-op compression that didn’t find any effect on seroma rates after breast surgeries, if anyone is interested: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10519563/

I wish more people would understand transition in these terms, including some of the people who choose it. It’s not a solution to all life’s discomfort, because such a thing cannot exist. It’s just a choice, which, if it makes it easier for a person to be in the world, is good enough for me.