Is Your Fear of Gender Transition Really the Fear of Aging?

Time & experience change all bodies, including in ways we might dislike.

Zander paused his transition because he couldn’t stand looking like his dad.

It wasn’t only that his father had mistreated him as a child, though he had. Zander had numerous male cousins who were tender and silly whom he’d also increasingly come to look like, and that helped reduce the pain of resembling his abuser. And the main problem wasn’t the awkwardness of becoming a powerful man after living a lifetime in the fear of men’s power, either. Zander had done what he could to make peace with that.

What really shook Zander about his paternal resemblance was the memories it brought up — of his father on his sickbed, his hair thinned like a passing cloud, his stomach distended with illness, his spotted forehead shining with sweat.

“When I look at myself in the mirror and I see myself looking especially hung over or crappy, I see my dad when he was dying,” Zander said, “All that was left of him, after everything.” He’d never been brought so close to his own mortality.

Zander said he was embarrassed that this had been enough to keep him from taking his regular testosterone shots. Transition had pulled him back from the brink of suicide ideation and compulsive substance use years before, and helped him feel capable of courting the pillow-princessy femmes that complimented his stone-top self. As an man he’d always felt confident, strong as any of the guys, sexy, sporting, and energetic enough to keep ladies’ toes curling all night long.

But now his back was aching. If he slept in an unfamiliar place, he groaned with pain the following two days. There was a tension in his hips and shoulders that a physical therapist had suggested was caused by his growing, muscular frame. Papery folds formed around his eyes, which looked so small and tired in his rounded, balding head.

Had taking hormones done this? Zander hated feeling anything like transition regret. Gender transition had brought so much goodness into his life, and empowered him so much — but now his body was changing in ways that didn’t make him feel stronger, more authentic, or more desirable.

Zander isn’t foolish or a betrayer of trans people for feeling all these things. Though the desire to detransition is often regarded by our community as taboo, we all internalize the world’s transphobia at times, and develop ambivalent feelings about our bodies. And it certainly wasn’t unusual to want to walk certain hormonal changes back. We can’t control which hormonal effects we get and which ones we do not, and that can be unsettling, no matter how much relief transitioning brings.

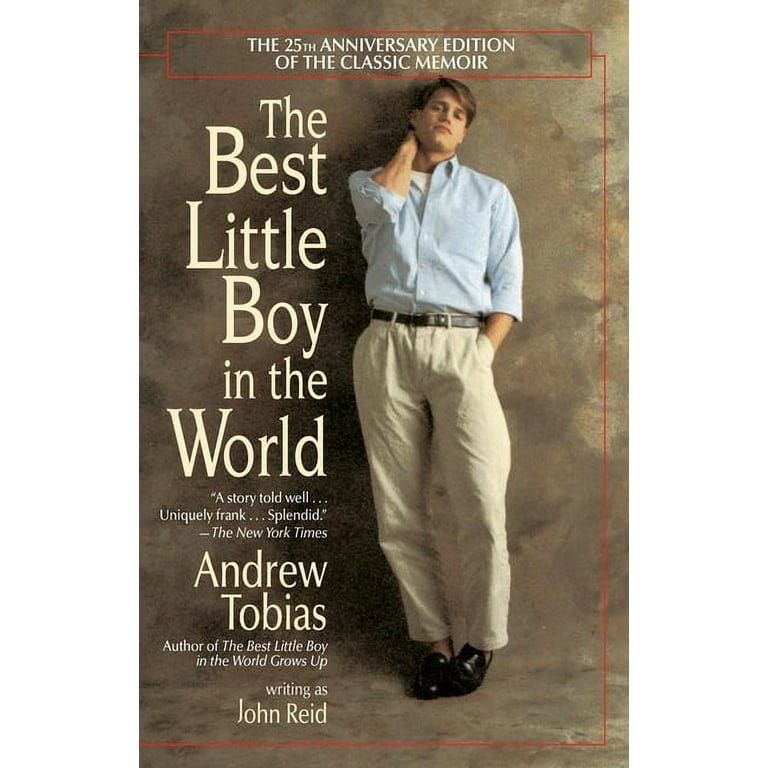

I told Zander I had taken my own miniature T-break just a few months prior, last spring, because I was anxious about my dull and wrinkled skin. I was looking older, and though I was ashamed to admit to such vanity, it had really affected me. Eternal bright and youthful cuteness felt like what I owed the world. Who would listen when a life of squinting and scowls caught up to me? I had to be the bright cheery Best Little Boy in the World to be listened to!

I was ashamed of how I had “made” myself look, but even more ashamed of the shame. I restarted testosterone only a month or so later, and continued to work on embracing my world-weary handsomeness. But still, whenever I wasn’t sufficiently hydrated or the light from snowy skies left my face looking especially grey, it got to me.

I researched the cost of getting a few dozen units shot into my face. Whenever I felt especially stiff or a Zoomer gasped upon learning my age, I asked myself: do I really have what it takes to grow old as a man?

Over the summer, a nonbinary, trans-masculine friend admitted to stopping testosterone because of their thinning hair. Then another told me they were uncertain about moving forward with their transition, because they had no image in their mind of the kind of older person they wanted to become.

A Jewish trans guy that I knew confessed he feared becoming the balding, short old Jewish man of the worst antisemitic stereotypes. A trans feminine friend said she’d stayed in the closet for a decade because she believed she was already too “old” to make an appealing woman. After all of these powerful speakings of shame, Zander reached out to me.

Zander wished he could rebel against the folding and creaking of his body. Having transitioned in his thirties, he only got to be a strapping young man for a very short time. I told him understood, that I too felt denied of an imagined, carefree youth that so many queers never really get to have, that when I take to yawning at the club at twelve in the morning I want to slap myself in the face and scream, “This isn’t me!”

But it is me, this tiredness that I carry, just as much as my springy tufts of hair or my memories. In my cutoff t-shirts and stainless steel chains I do broadcast part of who I am, but my clicking elbow and the frown lines from my divorce complete the story. Like Zander, I am a man who denied himself everything, and then one day unloosened himself and got stronger. But I have to get weaker too, it’s the way of all living things — to shuffle, groan, and one day stop.

It still will have been better to live as the man that I am than to have remained entirely checked out of my body forever, fighting for relevance and acceptance as a woman.

…

So many of the fears people have about transition are ultimately fears about aging.

We don’t want to go bald, or to see our boobs sagging; we don’t want to grow hair on our backs or resemble our mothers and fathers rather than the heart-throbs and anime characters of our early gendered fantasies. We are afraid of losing fertility, skin elasticity, and muscle, or gaining fat. We don’t want to make do without hard-ons or vaginal moisture; we don’t want to be considered unsexy and out-of-touch. Most of all, perhaps, we live in terror of taking some action that we cannot take back, of having bodies forever overwritten with the irreversibility of time.

Of course, we are made to feel this way by legal, medical, and social systems that regard medical transitioners as defective freaks who are tolerable only if there aren’t very many of us and we have no other choice. Transgender people don’t harbor these anxieties out of random vanity, or because our ideals are any less realistic than any cis person’s. Our shame is systemic: the trans body is the site where a cissexist culture places so many of its anxieties about loss, disability, undesirability, and change.

This is a subject that Lily Alexandre has explored expertly in her video, Fear of Trans Bodies, and if you haven’t seen it before I recommend checking it out:

Every transgender person living today has been exposed to a suffocating amount of fear-mongering about our bodies, from the balding, tattooed depiction of Jame Gumb in Silence of the Lambs to Abigail Shrier’s endless dramatics about trans guys’ hysterectomies. We take all this in and develop complexes about wearing gender-affirming clothing that looks too “young” on us, and beat ourselves up if we develop genital atrophy and lose some bone density.

But ultimately, all of these fears are about aging. Why is a bad thing for a woman to be bald? What is wrong or upsetting about an older person wearing revealing clothes? Why is it that a hysterectomy brings ruin to a trans man? Aren’t atrophy and osteoporosis already risks of leading a life for long enough?

As Lily says, “Transition is just a body changing as it moves through time. Your body fat shifts, your genitals change, your hair gets thicker in some places and thinner in others. It’s impossible to disentangle this from aging, because they’re basically the same thing!”

I spoke with a variety of trans people for this piece, and asked them about their relationship to aging. What I heard repeatedly was that moving forward with transition required them to accept the changing nature of their bodies, and the inevitability of aging and death.

“Transitioning has for me felt almost inseparable from aging,” writes Lichenid, a nonbinary transfemme. “The aspects of being ‘a man’ that I found comfort in (strength, athleticism, fertility) were ones that decline with age, so losing them even faster from taking HRT felt like embracing that process?”

Lichenid said that growing older as a woman felt far more right for her than growing older as a ‘man.’ Still, it was a major change, because women are viewed as old at far younger ages than men are. “I’ve managed to go from a (relatively) young man to an ‘old’ trans woman in the space of about a year,” she says, “and it is a little jarring!”

This was echoed by a trans butch woman, Pallasinine. “The fear of transition for trans women often has more to do with a fear of ALREADY being too old…Especially with the way that aging facilitates a kind of degendering.”

I was initially shocked to learn Pallasinine was saying this at only 26 years old. From where I’m standing ten years to her senior, that age looks impossibly young. But I do remember being in my mid-twenties and hearing female peers lamenting their oncoming wrinkles and waning fertility. If a cis woman can be concerned at 26 that she’s nearly “too old” to have children and needs to start preventative Botox, then of course a trans woman can believe that she’s “too far gone” to ever become an acceptable type of girl.

Misogyny’s demand that women remain young, unsettled, and readily exploitable certainly runs that deep.

Multiple trans people mentioned a commonality between ageism and anti-fatness: the older you get or the larger your body is, the more likely people are to deny your gender. Fat men and old men are seen as lesser types of men because they are weaker and softer than men supposedly ought to be. Fat women and old women have failed to keep their bodies conventionally attractive and capable of providing unceasing caretaking labor, and so they cease to be women, or even people.

“I gained about seventy pounds on testosterone because I stopped purging and using drugs,” says Lyam, a trans man. “I feel really good. But I think a lot about how people see me as this round little man with small hands. I am kind of a cartoon.”

On most days, he says he is fine with being so far from the conventional man. But it doesn’t make being in locker rooms or crowded subways any easier.

Several trans masculine people remarked that as their transition progressed, they moved rapidly from looking “too young” to “too old” for their actual age. Many trans mascs initially read as youthful because they’re shorter than the average man, with larger eyes, shorter philtrums, or softer skin. But as their beards grow, their hairlines recede, and their skin texture and body size changes, they may suddenly morph into a mature appearance.

The fear of this sudden shift — and the mix of privilege and relative invisibility that so often comes with it — can leave many a transmasculine person pausing their transition, or disavowing any connection to “manhood” altogether.

“I’m not really a man, I’m more of a boy,” is a refrain that many a trans masc has been heard to utter. Some trans men even claim that starting HRT is such a vulnerable experience that it psychologically de-ages them, and they should be held to the same standards as teenage boys.

The “birthday boy” phenomenon is a genuine problem within the trans community, in which a trans man attempts to eschew adult responsibility (or be held accountable for misogynistic actions) by likening himself to a child. There’s a dramatic fear of adult, male responsibility on display here — and it’s inseparable from deeply ingrained societal fears around aging.

Adult men are large and scary, with the capacity to harm others, the perennial boys seem to think. To be oppressed or lack physical might is to never fully occupy the position of manhood at all. And there is a lot of truth to that feeling — but it does not change the fact that as our chests expand, our voices lower, and our wages go up, the women around us do grow deferentially silent.

Similarly, the forward march of time is non-negotiable, and with it we accumulate experience, wisdom, jadedness, social connections, institutional knowledge, and perhaps a little money and authority. This influences how other people respond to us, whether we like it or not.

I remember what 9/11/2001 was like. And while I might find that fact embarrassing when it comes up at a mixed-generation house party, it comes the years of wisdom and professional experience that also help me write recommendation letters, fix errors on invoices, and talk down irate neighbors who want to call the cops.

Growing older doesn’t just mean losing elasticity and growing less attractive to the dewy-faced masses. It can also confer an authority that protects us (until it progresses even farther, and we aren’t respected as competent adult humans at all).

Several trans people told me that aging has felt awkward, because they lack the sense of style or social skills expected for a person of their age. For nonbinary people this was especially vexing, because social expectations and milestones for their gender don’t really exist at all, and androgyny is mostly associated with feckless youth.

“[The] fear of not knowing how to dress or do your hair or makeup ‘appropriately’ mirrors stuff my mom and auntie have spent a lot of time talking about as they age,” writes nonbinary trans femme Maybeseveralthings.

They shared that they were concerned about dressing like an old woman or seeming too desperate to look young. Many of the insults that conservatives lob at enbies concern this — they’re stereotyped as eternally “childish” with colorful haircuts and cartoon character t-shirts their critics consider pathetic. They are seen as unserious and undeserving of accommodation — their gender a childish phase, not a real identity that could move through any number of stages.

When we transition, our lives often change quite dramatically, which can leave many of us feeling scrubbed raw and embarrassingly exposed. My ten-year relationship ended when I became a man, and my life became far less structured and traditionally ‘adult’ as a result. I kept odd hours, downsized my apartment and possessions, completely redid my wardrobe, and went out partying with other queer people often many years younger than myself.

To some, I might have appeared to be in a state of arrested development. In actuality I was restructuring a life that had come undone, and moving away from more conventional concerns. I wasn’t really any less of an adult because I had a ratty self-shorn haircut, no car, and dressed like transmasculine Tweety Bird. I was becoming man enough to claim the things I wanted and cast off all the rest.

It’s quite common for trans people to break free from the societal mold in ways that provoke social judgment. Living with roommates, having multiple romantic partners and lots of casual sex, socializing in nerdy, kinky ways, dressing for comfort or to express one’s artistic side, not having children, not working at all — these are stigmatized choices, because the only acceptable vision of adulthood in our society is one that produces both fruitful labor and offspring who will one day themselves provide labor. And so many trans people struggle with visions of themselves as immature, unformed, or “wasting” their lives.

Zander tells me that he finds it difficult to reconcile his mature, masculine appearance with his inner sensitivity, which people have always said looks “childish” in a man.

“People say men should cry more,” says Zander. “But I can’t make it happen. I see a sad, weak man in the mirror, and I cannot stand that.”

I can cry just fine, but aging into manhood has given me some similar anxieties. I fear being too creepy. I am disgusted by my own enthusiasm at times. I fear my shyness is no longer acceptably cute but pathetic. The clock has run out, I get to telling myself, and I cannot expect anyone to be patient with me.

I can acknowledge that for a 36-year-old, this is absurd. But it speaks our culture’s ageism that I can so easily feel that my life is too far gone. In its moldability and potential for abuse, youth is celebrated. A person that hardens, breaks down, or knows themselves well enough to get set in their ways is far closer to socially disposable.

Reactionaries obsess over ‘protecting’ youth from gender transition because young people can still be molded into a desired shape — they are far easier to control and abuse. But the trans elder is not so worth saving. They’re too resolutely themselves, too hard to be made back into a useful tool.

That’s part of the fear of transition, ultimately — that we are asking too much, making ourselves too unemployable, wanting a life that does not legibly exist — that the longer we persist in fighting for our freedom, the harder it will be for us to crawl back into compliance if we have to.

Several trans people mentioned fearing uncertainty, as it relates to both transition and aging.

The result of transition is unknowable when we begin. What size will my breasts get to? Did I start hormones young enough to get taller or shorter? What will dating be like when I look different? Will my children be ashamed of me? Which friendships will change? When I look back on it all forty years later, will my authenticity be worth whatever I lost?

These are all existential questions: what does it mean to be the person that I have chosen to be? Could I ever have been someone else? We make our choices in real time, and we can’t know how the truth will settle upon us.

Even the fear of transition regret is a resistance to the irreversibility of time. Life’s options inevitably winnow down as time advances, whether we make decisions or not. It is a loss of exit routes, but it’s also act of cementing and building upon what’s been there before.

Before I ever admitted I was transgender, I kept a log of male style inspirations on my Tumblr that I tagged #boysonas. The “boys” that captivated me were largely effete, soft spoken creative men with greying temples and lines around their lips. People like Ira Glass, Mads Mikkelsen, Rami Malek, Damon Albarn, Anthony Bourdain, Richard Ayoade, and Raul Esparza.

These were not boys, these were forty- and fifty-something men with a tired reflectiveness and a dry, sad wit about them, and they were beautiful to me, just beautiful. I had always wanted to be like them, yet I started to recoil when I saw those same lines and greys on me. Why?

There was a finality to my aging, a closing of life’s doors I could feel. Damon Albarn’s path from irreverent pop heartthrob to grizzled musical mentor was his story, and an admirable one at that; my progress in life was a loss of all the other people I thought I could be. From anyone else’s perspective, time and experience were seasoning me, making me into the man I was meant to be, and my ultimate story made sense. But I was the person living that story, and I didn’t want there to only be one. I wanted to choose all the adventures.

Every choice leaves its marks on us, given enough time. As I write this, I am healing from a severe tear of my FPL tendon caused by years of over-exercising and furious typing. My knee still hurts sometimes because I spent all of 2018 at a standing desk. My muscle development will always be NERFed by the fact I took hormonal birth control. These are the costs of a life lived; why can I accept them but not the effects of transition? Even no choice is a choice.

There is no taking any of this back. I will only ever be this person. And thank God, because I didn’t take good enough notes to retrace my steps.

What is there to be done, then, about how transition can activate our fear of aging?

Doing away with one’s ageism is the obvious response, but that’s easier to say than to live.

Surrounding oneself with older queer people is advice that several folks mentioned, and it’s one I would strongly echo. Some of my dear friends are gay & transgender people in their 50s and 60s, and they’re as capable of impulsive, dramatic romances and hilarious mishaps as anyone else. We all listen to newly released music, watch new plays and movies, make references to figures from Old Hollywood, and struggle to get the Snapchat app to work together — we are old and young in all kinds of ways.

I’ve experienced some life milestones before my older friends have, like burying a parent, and we can relate about these challenges on about equal footing. But I can also lean on older people for advice about cleaning out an A/C unit or drawing up a will. Quality time together disproves all the empty stereotypes about generational difference. I see my older friends as peers who just so happen to know a ton about eras I wasn’t around for.

I am so blessed to get to talk to people who were conscious adults during the first appearance of AIDS. I know Mad Men fans who are the same age as Sally or Megan. On the flip side, I have a few Zoomer friends who find the early Y2K period and the 1990s fascinating, and when I get to explain the history of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell to them or introduce them to Bloc Party, I feel I’m inviting them into a shared secret world. This is who I once was, I remember, I was there.

For all the generational knowledge that I possess, my older friends contain an order of magnitude more. They are living treasure, irreplaceable. And in my dotage I will be too.

“Forming close friendships with old dykes has been vital,” says Lou, a trans dyke in her mid-twenties. “Really lucky to have some in my life who are kind to trans people.”

Lou mentions that close friendships with older gender non-conforming women has made it clear that her own sexual appeal does not depend on prettiness or youth. Older dykes are sexy as hell, with their buzzed heads and boot cut jeans. “You can start to realize that maybe maintaining that culturally dominant form of attractiveness isn’t a priority for you either,” she says.

This was echoed by Tumblr user MoriarTeaParty, who says, “When I started T, I had to unlearn a lot of shit like internalized fatphobia and aging. I think it finally clicked when I realized I find older men incredibly hot and was like, Wait. But that would make ME hot too.”

“As a nonbinary person, one of the things that helped me was seeing old GNC people on TV, especially queer men!,” says Apollo. “Off the top of my head, Santiago from the AMC adaptation of Interview with the Vampire was an absolute revelation to me.”

To my fellow fictional old-man fuckers, might I also humbly recommend having sex with actual old men? There are 65-year-olds who will undress you with the fervor of a horny teenager, then pound you into the mattress with resolve that’ll put a 30-something gym rat to shame. So many new possibilities opened up to me the moment I set aside my reservations about being with dramatically older (or younger!) partners, and I’ve had some downright fascinating pillow-talk in the process.

Unlearning our collective ageism isn’t all about salivating over sexy liver-spotted bodies, of course. A number of trans people told me that continued survival was their single biggest motivator for embracing aging & transition, and that they wore every wrinkle like a victory badge.

“A big watershed moment in my decision to start taking HRT was thinking about growing older,” says Fuzzy, an agender person. When they were nineteen, they say they were visited by a vision of themselves as a dignified, middle-aged person who leaned on a cane, standing in a faraway fog.

They say, “It was the first time I seriously entertained the possibility that I might be allowed to grow old.”

Fuzzy says they accept that taking HRT could theoretically give them bone-density issues, and pursuing gender nullification surgery could increase their risk of early incontinence. These losses are “unexceptional,” as they put it— exactly like what so many elders undergo. Fuzzy says transition gave them a future, and living in a normal, mortal human body is well worth that trade.

An anonymous commenter told me, “I got comfortable with aging after I tried to off myself at age 19. Every time I gain some trait of being ‘older’, I feel grateful because I could have died and stayed the same age and appearance forever.”

A trans woman shared with me that after numerous years in the closet, she presented herself with a thought experiment: “Would I have pressed a button to become a woman if it also aged me 10 years?”

The answer was an unequivocal yes.

“I think about that every time I start to feel age-related transition anxiety and it calms me down,” she says.

Like many trans people, I found my future life difficult to picture before I started HRT. All that I knew was what I did not want the kind of life that had been presented as my sole option: parenthood and economic independence, living in a single-family home.

Watching my mother and grandmother age in a small-town condominium with a two-car garage, I still don’t have a great model of what my own old age will be like. It does sadden me to think about sliding around on the icy Chicago sidewalks at age 86, on my way to catch a bus. But that fate is largely a failure of my culture’s imagination, not a problem with either transition or aging.

My friend Sarah Yuile belongs to the tangata whenua (people of the land) of Aotearoa (which settlers called New Zealand), and she says her culture has prepared her to approach aging in a healthier way.

“Aging is seen as a process that comes with wisdom and mana and is therefore not a negative thing, but something of honor and comes with a lot of respect,” she explains. “I’ve never been concerned with the ideas of getting old or death. I also recognize that life gets easier as you know yourself better and accept who you are, and usually that process goes hand in hand with age. I would never want to go back in time, not even physically.”

I have been thinking a lot about how the limited number of roles provided to elders by a predominately white, colonial capitalist society. If an older person cannot work, drive, or run errands for themselves, they become like a ghost: rarely seen or acknowledged, perhaps feared, and only appreciated as the person they might once have been. There’s no meaningful task to fill their days, few social spaces they can occupy and no means of getting there, and no one actively seeking their wisdom.

This economic system is so cruel and dehumanizing to elders that even members of the ruling class are forced to march their ailing bodies to the Senatorial podium and work sixteen hour days, pretending to be their former selves even when they’re no longer cognitively there. If a person with as much power as Diane Feinstein or Mitch McConnell can be leeched of labor until their dying breaths, there’s little hope of this system showing any regard to the rest of us.

But we need not conceive of old people like a junkyard worker stripping a car for parts. Indeed, the majority of humans who’ve lived on this planet have not. They regarded their elders as powerful and insightful, and sought their counsel without forcing their bodies to work or remain compliant.

Creating a hallowed place for older people to occupy has been absolutely essential to the functioning of many societies. In fact, according to many anthropologists, human social evolution didn’t really take off until members of our species started living long enough to become grandparents.

Multi-generational groups of human beings could accumulate skills (like sewing and food storage) and knowledge (like the patterns of floods), and could also build upon it like never before. Grandparents helped raise the next generations of children, freeing up a great deal of time for other adults, and cementing bonds with families and their own kids.

Elders could maintain traditions, pass along recipes, prevent the retreading of old mistakes, tell tales of long-ago battles, and bear witness to new life. They could sit upon councils, lead ceremonies, and be buried with honor. With their lives and their deaths, elders gave their societies whole new ways of looking at death, architectural construction, and art.

My paternal grandmother was a remarkable storyteller who grew up in the hilly Cumberland Gap of Tennessee. She learned how to drive at age eight, taking her alcoholic parents home from a bar tucked away in the Appalachian mountains. Her classmates considered her snobby because she was curious and intellectually-minded, and had decided to give herself a middle name (almost no one else in the community had one).

My grandmother spoke with me frankly about the anti-Black racism she had been indoctrinated into as a child, as well as our family’s mixed heritage, and the reasons some of our relatives had chosen to “pass” as white. An eternal seeker, she joined and quit many churches in her day, and after the death of her husband enjoyed a sexual renaissance in her 40s and 50s. She filled her home with antiques, fancifully dressed Steiff teddy bears, and books about spirituality and sex that I was allowed to read as a curious child.

My grandmother listened to me as no other adult could, asking me about my opinions and really caring to hear the response. She was a warm, fun-loving woman with a fiery spirit of defiance, and absolutely everybody loved her. My uncle says that he would give anything just to feel one more of her hugs; I would sacrifice so much just to share in one more conversation with her.

But in order to commune with my beloved late grandmother, I don’t have to give anything back. I only have to keep living, and growing older, fulfilling the role that she once played in my own way.

My grandmother lives on when I sit down and ask somebody how they are and actually listen. Her spirit moves me to call my uncle, write a long letter to my niece, put on some gaudy jewelry, and make up songs while I rock in my chair. I can find a piece of her in the bottom of a Jello shot (the pink lemonade ones were her favorite), and when I paw through the teacups in a resale shop.

I am at my best when I embody the qualities she passed along to me, and I can imagine for myself an old age that was as fun as hers: filled with shopping for knick-knacks, careening around town belting Willie Nelson songs, and playing Uno while eating fried cream cheese and jelly sandwiches. She was playful, fashionable, compassionate, intelligent, and dazzlingly sexy for all of her years, even when she was dying and took her dentures out. I can aspire to be the same.

There are so many esteemed roles we might get to play as we age: the wizened crone, the witch, the eternal trickster, the gift-giver, the marker of time, the mentor, the hermit, the professor emeritus, the high priestess, the midwife, the symbol of death, the source of life, the fount of eternal love. None of this depends upon our gendered qualities or the capabilities of our mortal bodies. The more we release our attachment to such fleeting things, the more the enduring truth of us get revealed.

We are what’s still there when we’ve lost almost everything. And no matter our age, life will can continue to surprise us with the many kinds of people we’ll be. There is no knowing for certain which effects our hormones will have, how the surgeries will settle some forty years later, what we’ll regret, what our choices will ultimately mean. There’s no taking any of it back, and always the potential to keep building upon it.

What a gift to keep on not knowing, to continue being capable of change.

Thank you so much for writing this piece, Devon, as usual you manage to synthesize and articulate the jumbled thoughts and feelings of many of us, while validating, de-stigmatizing, and normalizing diversity.

I've been thinking about aging a lot recently, not having started transitioning until I was nearly 50. The gender-affirming changes I've experienced have occurred just as I passed the cusp of middle age, and so I've had to become comfortable with my body metamorphosing in both joyful and terrifying ways simultaneously. While I'm reveling in the redistribution of fat to my hips and breasts, and my considerably softer skin, I'm also learning to accept that I don't have the energy or physical strength I used to, that my face is losing its formerly youthful look, and that my hair is noticeably thinning.

In addition to the loss of privilege I've experienced as a visibly transgender woman, whose validity and relevance was already in question, I also now have to come to terms with being an *aging* visibly transgender woman who can no longer rely on the bloom of youth to win any favors from the male gaze. As I increasingly recognize older women as my peers, however, one thing I'm noticing is that despite the indignities of frequently being silenced or ignored or talked over, older women know A LOT, and are incredibly capable and wise. I'm looking forward to continuing to count myself among them.

fuck yeah swag gmas