'The Telepathy Tapes' is Dangerous, Unscientific Nonsense that Promotes a Widely Discredited "Communication Method" Used to Abuse Autistic Kids

Facilitated Communication is bunk, with many facilitators having used it to put words in the mouths of children. This massively popular podcast is just the latest instance of abuse involving FC.

I have been getting a lot of questions lately about the incredibly popular podcast The Telepathy Tapes, which briefly unseated The Joe Rogan experience as the most listened-to show on the Spotify charts this past fall, and has been occupying a comfortable position in the top five most popular podcasts ever since. The Telepathy Tapes has an enviable 4.6 star rating on Apple Music and a 4.8 on Spotify, with nearly 5,000 reviews on each platform apiece, and the show’s been covered everywhere from Variety and The Atlantic to the Rogan-esque Jay Shetty show.

For the uninitiated, it’s show about how nonverbal Autistics have psychic powers. Yeah, I’m distressed at how well it’s caught on, too.

Per Spotify, “The Telepathy Tapes dares to explore the profound abilities of non-speakers with autism - individuals who have long been misunderstood and underestimated. These silent communicators possess gifts that defy conventional understanding, from telepathy to otherworldly perceptions, challenging the limits of what we believe to be real…Through emotional stories and undeniable evidence, The Telepathy Tapes offers a fresh perspective on the profound connections that exist beyond words.”

Much of the ‘undeniable evidence’ that The Telepathy Tapes relies upon comes from the practice of facilitated communication (FC), a widely discredited interpretation method in which an abled facilitator supposedly draws words out of a nonverbal Autistic client by taking hold of the client’s arm or hand and “assisting” them in typing out meaningful messages.

Before I dive into the problems with FC, I want to briefly affirm that many nonspeaking Autistic people can express themselves in words using tools such as letterboards, Augmented and Alternative Communication (AAC), sign language, keyboards, or other methods.

A number of Autistic people that I have interviewed for my books have communicated exclusively via text or AAC; my friend Angel, who I speak about in Unmasking Autism cannot speak, but can fill up the Tumblr chat box with memes and messages with the fiendish energy of any other gabby teenager.

Another nonverbal Autistic friend of mine, Charity, writes her messages by maintaining a giant text document filled with her most commonly-used words; she can’t type, but she can select these words manually and paste them together, in a somewhat painstaking fashion, to form whole sentences. The blogger Ido Kedar famously is unable to speak, but has used his iPad and letter board to complete high school, enroll in college, maintain his blog, and author multiple books.

Beyond this, numerous Autistics who cannot communicate in words at all are nonetheless competent, complex human beings with an ability to signal what they want and how they feel using vocalizations, body movement, self-stimulation, self-harm, and a variety of modes of behavior. Behavior itself is communication. That Autistic people of all ability levels have interiority and the capacity to express themselves is in no way subject to debate here.

Unfortunately, multiple generations of nonspeaking Autistics have been completely denied the chance to express themselves in the ways that suit them, because instead of being given tools like AAC devices or being trusted & listened to when they used their bodies to communicate, they were forced instead into facilitated communication — a speaking person took hold of their body and manipulated it for their own ends, putting their words into the disabled person’s mouth.

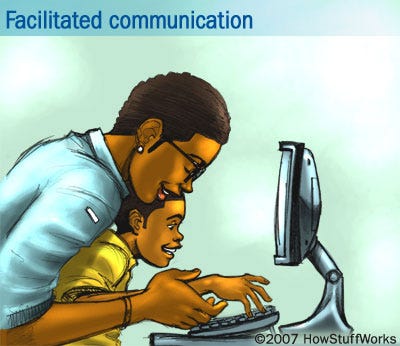

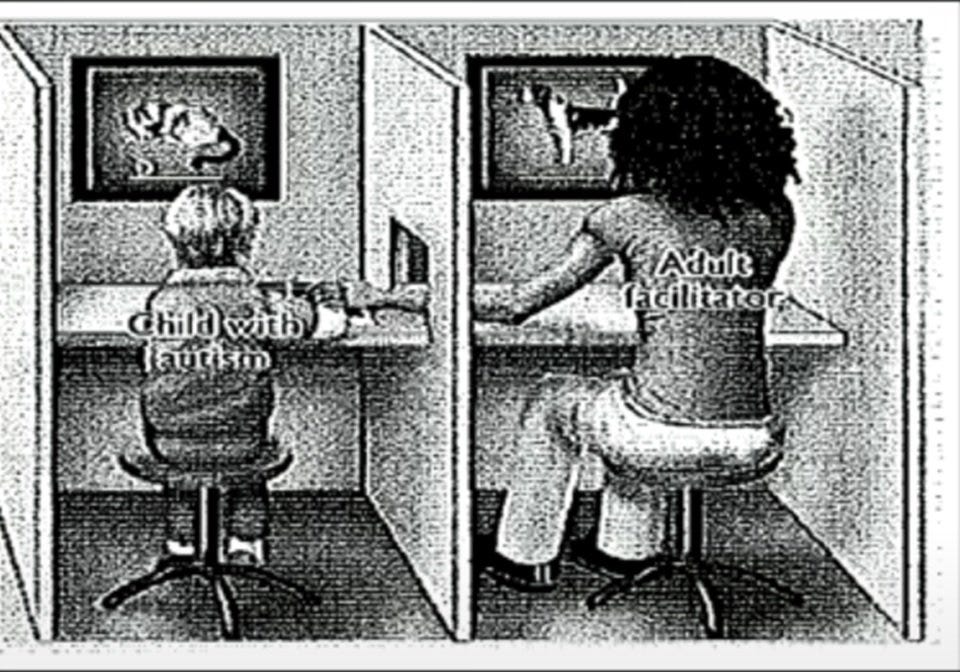

Above, a demonstration of what facilitated communication often looks like in practice.

Facilitated communication (also known as assisted typing, supported typing, or the rapid prompting method) was introduced by a variety of different practitioners and support staff throughout the 1960s and 1970s — it seems many care providers who worked with Autistic kids each independently had the idea of being a disabled child’s “voice” by helping them type.

The facilitated communication method was dismissed as unscientific by practitioners in Denmark in the 1970s. Then, FC reemerged in popularity throughout the 1980s and 1990s largely thanks to the advocacy of an Australian special educator named Rosemary Crossley. News articles throughout the period celebrated FC as a revolutionary new method that could help bring notoriously hard-to-reach Autistics outside of themselves. Gruesome accusations of child sexual abuse were collected by teachers and specialists using FC on their nonverbal students, leading to incarcerations even when there wasn’t any other evidence.

Facilitated communication was experiencing a major boom. And then, over 40 peer-reviewed studies came out showing no evidence that facilitation communication actually worked — virtually all of it suggesting that facilitators were ‘interfering’ with nonverbal clients’ reports. Throughout the 1990s, the American Psychological Association, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, and the International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication all issued strong statements against the use of facilitated communication, all of which stand by it to this day.

To quote from the American Speech-Language Hearing Association’s current guidelines on the subject:

FC is a discredited technique that should not be used. There is no scientific evidence of the validity of FC, and there is extensive scientific evidence—produced over several decades and across several countries—that messages are authored by the "facilitator" rather than the person with a disability. Furthermore, there is extensive evidence of harms related to the use of FC. Information obtained through the use of FC should not be considered as the communication of the person with a disability.

The thinking behind FC isn’t totally unsound — one of the reasons that many Autistics find it difficult to speak is because the precise fine motor control required to move one’s tongue and lips and produce words is challenging or impossible for us. A similar difficulty with fine motor control in the hands can also make it challenging for us to hold a pen, hold a cup or a fork, or type on a conventional keyboard. We also, as a community, tend to have reduced muscle tone and hypermobile joints compared to non-Autistic people, both of which can make tasks such as writing and typing far more difficult.

(I certainly can attest to that, as I compose this draft using a vertical mouse, with a soft L-shaped bracket of foam glued to the edge my desk to prevent my tenosynovitis from flaring up).

Based on these facts alone, the idea that an abled assistant could give an Autistic client’s communication abilities a boost by lending a supportive arm makes some sense. But where facilitated communication goes wrong is in its trust of the abled facilitator to serve as a neutral amplifier of the disabled person’s actual words and desires. Instead, what the science has found consistently is that the messages composed using facilitated communication reflect the thoughts, knowledge, and feelings of the facilitator themselves — including in instances where it would be impossible for the disabled client to possess the same information.

Results indicated unequivocal evidence for facilitator control: messages generated through FC are authored by the facilitators rather than the individuals with disabilities. Hence, FC is a technique that has no validity.

It is fairly easy to test the validity of facilitated communication — which might be why the method has managed to be discredited and thrown out of favor multiple times in its over fifty years of existence (only to resurge in popularity again a few years later, when a new generation of desperate abled parents turn to it in hopes of reaching their supposedly locked-away kid).

Many of the experimental studies of facilitated communication look something like this: an FC facilitator and their nonspeaking client are each taken into private rooms, and given contradictory information, which they will later be quizzed on using FC. For example, both might be shown a toy chest with an item hidden inside it — the nonspeaking client might be shown that a soft white teddy bear inside the chest, and the facilitator, a long-haired Barbie doll. Once they are reunited, the nonspeaking client is asked to type what they saw inside the toy chest. With the helpful facilitator leading their hands, they reach out and type…that they saw the long-haired Barbie.

Numerous studies have been performed in this vein over the years, in each one the researcher providing the FC facilitator with information that their nonspeaking client could not possibly know, then finding that once the two are sitting together at a keyboard, the nonspeaking client just somehow…knows it. It is as if there is a psychic connection between the facilitator and the nonverbal Autistic. Beyond that, the average nonverbal client using FC writes with remarkable maturity and insight, their words poetically beautiful no matter their age or lack of prior experience. Parents of nonspeaking kids are understandably moved by such performances, and inclined to believe that FC works, and that even beyond that, that it might reveal their child possesses supernatural abilities. It’s like magic.

Or an abled adult has been pulling the strings all along.

If facilitated communication were nothing but a useless party trick that had deluded thousands of parents into thinking they were really speaking with their disabled kids when they weren’t, that would be bad enough. Unfortunately, FC is more than just an unscientific novelty — it’s also been used to facilitate sexual abuse.

In 2015, The New York Times reported on the sexual assault case against Anna Stubblefield, a white philosophy professor and FC facilitator who worked with numerous intellectually disabled and nonverbal people. Stubblefield allegedly used FC to convince the family of DJ — a young Black man with cerebral palsy and intellectual disabilities who could not speak — that their beloved son and brother was actually capable of profound thought and had initiated a sexual affair with her.

Over the course of years, Stubblefield worked intensively with DJ, using FC to “help” the young man write essays, deliver conference presentations, and even enroll in graduate-level college courses despite having never completed a pre-school level education or even been taught how to write. Stubblefield held private meetings with DJ in her office on campus, where the two “talked” with Stubblefield guiding DJ’s hand across the keyboard. Eventually, DJ supposedly confessed his love to Stubblefield. Despite her claims of protest, the young man kept relaying passionate messages to her, and asking about intimacy and sex…until, Stubblefield says, she eventually relented and admitted to her own feelings, and the two consummated their relationship.

Stubblefield was charged with first-degree aggregated sexual assault, the court finding that DJ did not possess the capacity to write a single one of the messages that Stubblefield had attributed to him, and could not possibly have initiated sex in the ways that she claimed.

A documentary about the Stubblefield case called Tell Them You Love Me was released by Netflix in 2023, hitting the top of the streaming charts and receiving enthusiastic praise from viewers. The documentary outlines the problems with facilitated communication quite clearly — and yet, just as the film surged in popularity, so did the latest rebrand of FC.

One year later, a podcast utilizing FC to demonstrate that nonverbal Autistics have “psychic” abilities would sweep the podcast charts.

Facilitated communication takes advantage of the ideomotor effect, a well-documented psychological phenomenon in which a person’s expectations, wants, and thoughts can unconsciously influence their movements. The most well-known illustration of the ideomotor effect can be seen during any Ouija board session: though every person kneeling before the board with their hands on the planchette may claim they did not move a muscle (and may even genuinely mean it), their desires still cause tiny twitches in their hands that build until a tear-jerking message emerges from a long-dead grandmother. The ideomotor effect also undergirds other paranormal practices like dowsing or pendulum reading.

One 2017 study found that the ideomotor effect is strongest among people who are highly sensitive to stimuli. Pendulum-readers who are so highly sensitive may not consciously recognize that their movements are influenced by the information they are exposed to, yet in experimental studies, they demonstrably are. Interestingly, responses collected using a pendulum reflected more accurate and honest answers to questions for which the pendulum user knew the answer. It appears that the ideomotor effect can unlock highly intuitive, unconscious responses from people who do not even recognize that their bodies are making tiny gestures that suggest how they feel.

It’s likely, then, that a number of the people who perform facilitated communication have no idea that they are speaking for their nonverbal clients, picking up on subtle cues in the environment as well as their own existing knowledge and feelings in order to write messages that dazzle podcast listeners and leave parents breaking down in tears. What comes out during a facilitated communication session is a projection of the facilitator’s own unspoken motives — be they a white wannabe-savior longing to connect more intimately with a young Black patient, or a well-intentioned care provider desperate to appease an attentive podcast host.

Most of all, facilitated communication preys upon the desire among abled people to speak for the voiceless rather than to accept different ways of listening, and of being. Autism Parents have been taught through decades of fearmongering anti-vaccination propaganda and Autism Speaks public service announcements to view their children as trapped inside their disability, and to yearn for the day when treatment will allow the “normal” and neuro-conforming child inside of them to break free.

Nonspeaking children are often forced through relentless corrective therapies designed to make them speaking, and when this methodology fails (as it often does), parents fall back on abled facilitators who can make their children write like a neurotypical instead. If a parent is still operating with the value that ability is always superior to disability, and that the closer to neuroconformity a child can get, the better, then a well-written, persuasive message composed using facilitated communication can feel like an unfathomable gift.

Instead of having to rethink their methods of communicating with their child, learning to observe and honor their behavior, or questioning the priority they give to language skills, facilitated communication allows parents to keep approaching their disabled kids using the neurotypical script. And by making a nonspeaking child dependent upon an abled facilitator in order to (supposedly) express themselves, FC maintains the powerlessness and dehumanization of the disabled child.

Anna Stubblefield believed herself to be a voice for the most voiceless within society — Black, disabled people. She fetishized their isolation, appropriated their pain, and so thoroughly identified herself with giving them liberation that she couldn’t admit that she was forcing her own psychology into their heads, her body onto their bodies. She took the all-too-common white, abled self-martyring urge to help (and be seen helping) and reduced it to outright horror. She preferred to hear DJ speaking the words that she wanted to hear than accept him as he was, unable to form sentences, uninterested in the red wine and philosophy debates that fascinated her, and motivated by a completely different experience of life than her own.

By presenting disabled children as powerless yet mystical beings who can offer their families psychic guidance and emotional support through the filter of an abled facilitator, The Telepathy Tapes continues in this terrible tradition of exploitation and abuse. It seeks to comfort the abled by suggesting that the disabled really are just like them, deep down, and that those who lack certain abilities can still justify their lives by possessing supernatural ones. In the world of The Telepathy Tapes, no concerned Autism Parent ever has to hear their child spamming the “no” button on their AAC device, or watch them frustratedly tear at their own hair. They never have to question their expectations for their disabled children, and all the careful scripts they wrote for their families long before those children were born. All they have to do is count on a little magic.

But disabled people are not magic. We are human beings — with all the difference, struggle, frustration, and lack that can entail. Being a human doesn’t necessarily mean possessing the ability to write sonnets or weep at the cinema, to put together words, be thankful for one’s caregivers, follow rules, meet demands, or ever lift a finger. And when we attempt to parcel the people who cannot do such things out of humanity, everyone is harmed, and our ability to communicate beyond language and across ability levels is destroyed.

The podcast Conspirituality has a fantastic episode on the many, many problems with The Telepathy Tapes — from the unconscious cueing that the facilitators are shown to be using on video to lead nonverbal children to their chosen answers, to show host Ky Dicken’s faulty testing method that involves giving facilitators the answers to questions posed to nonverbal kids, to the show’s blatant misunderstanding of how developing language and reading skills typically works. Conspirituality is a podcast that explores how pseudoscientific and magical thinking is often used to launder reactionary or downright facistic views — and The Telepathy Tapes is very much a part of a pipeline that leads from talking of “highly sensitive persons” and indigo children all the way down to antivax sentiment. I strongly recommend giving the episode a listen.

Having worked with non verbal people for a long time, and witnessing interactions between support staff and these people a lot of this can come down to the support person wanting to feel special by claiming to have some unique bond with the individual.

It’s true that you can develop a strong working relationship with someone over time that means you understand their subtle communication cues, but nothing should ever been assumed as true and correct unless the person has emphatically confirmed it.

AAC can be great, but still relies on the support person being open to actually receiving what has been said and accepting it if it goes against their own beliefs/preferences. This is especially true if it’s about anything sexuality, or basically anything that challenges how we think disabled people should act. Devon I’ve told you some stories around this…

I haven’t listened to the podcast. But it doesn’t surprise me that people claim to have telepathic bonds with disabled people. That implies a certain level of importance and is a control issue.

There’s a term in disability services here “client capture”. Outdated terminology but basically implies that a staff member has formed a non working relationship with the disabled person which prevents them from experiencing freedom and autonomy. That’s what all of this reeks of…

I also think people are mixing up “telepathy” with understanding each other. Just like any human beings you can bond with someone and get to the point where you know what a look means, share inside jokes with a glance, know what the other person is likely thinking in response to something etc etc etc

This is about Rapport. Not mind reading. We are all capable of this. Including disabled people. Some of the sharpest people I’ve met can’t speak but one look tells me they’ve absolutely understood the situation, and can tell what I think about it. It’s often an insightful social commentary they’ve picked up on. But we’re not using telepathy to communicate, just regular human interactions and relationships.