A Massive Study of 16,000 Participants in 23 Countries Finds People Are More Prejudiced Against Trans Women Than Trans Men

Are we ready to take transmisogyny seriously yet??

I have another Research Roundup for your inboxes this week — the series where I offer some context and criticism on the latest social scientific research. This time, we are taking a look at a groundbreaking new study on transmisogynistic attitudes across the globe.

The article A Cross-Cultural Investigation of Prejudice Against Transgender People by social psychologist Jaime Napier was just released in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science earlier this month, and it contains truly noteworthy findings that offer some of the first empirical support for decades of trans feminist theory.

It also includes some…telling gaps in the researcher’s understanding of how gendered bias operates, which is a really great indication of how far behind the field of social psychology is on the subject, and how little scientists from within our field listen to trans female scholars.

Let’s first take a look at the study abstract before diving into the nitty-gritty details of the methodology, findings, and Napier’s conclusions. I’ll summarize and provide additional commentary & critique to every passage of the paper that I share here, so if you find any portions difficult to follow, just keep reading along for my breakdown:

This is a study with an impressively large and diverse sample size, at least by social psychological standards, with over 16,000 participants in 23 different countries providing data on their attitudes toward trans women, trans men, and the general concept of whether changing one’s gender is possible. In addition to recording these attitudes, Napier measured her subjects’ gender, age, education, religiosity, and conservatism to use as potential predictors of anti-trans bias.

This study was partially inspired by previous research (by Bettinsoli, Suppes, and Napier herself, conducted in 2020) that found survey respondents throughout the world are more vocally prejudiced against queer men than they are against queer women.

Based on those findings, Napier suggests that in her study, trans women might be found to face stronger prejudice than trans men — but not because they are women, or because transphobia intersects with misogyny to create a novel form of prejudice called transmisogyny (a term that is not used once the entire article). No, Napier suggests that subjects in her study might be more biased against trans women because they really view trans women as akin to gay men, and gay men are more heavily discriminated against.

Now, there are several big issues with this understanding of gendered prejudice. The first is the notion that lesbians supposedly face less bigotry than gay men do. It’s true that when prompted, the average homophobic person tends to express less revulsion toward queerness in women than they do toward queerness in men. And indeed, this is what Bettinsoli et. al found in their 2020 study: people expressed less intense dislike for lesbians.

However, this finding ignores the fact that anti-lesbian prejudice often takes the form not of explicit hatred, but rather the view that queer female desire is illegitimate, unserious, and something temporary that women can be pressured and assaulted out of. Queerness is often viewed as an inherent part of who gay men are, making them irredeemable predators and perverts in the eyes of the homophobes, who then attempt to violently drive them out of public life. But when it comes to women, queerness is seen instead as a flaw that can be “fixed,” in order to restore a woman’s availability to men.

Just think of how some of the most widely-reported cases of homophobic hate crimes have gone, for members of both groups: men are brutalized for being gay, whereas queer women are forced to kiss one another for male titillation, and then brutalized.

Straight society pushes queer men out, but it rarely allows women to escape. Instead, it conditions them to prioritize the interests of men, to evaluate themselves through their desirability to men, to attempt to find something redeemable or attractive about men, and to submit themselves to men’s romantic advances regardless of their true feelings. It’s a quiet, insidious form of prejudice that can pervade the lives of queer women so thoroughly that many women don’t even realize they’re interested in women for decades. Queer women come out a later ages, on average, than queer men do — and that’s certainly not because they are less oppressed or face less bigotry.

There’s also the abundant social science data showing that queer women face an elevated risk of domestic violence and corrective sexual assault, almost entirely at the hands of men — because even exclusively lesbian women are still seen as available to men romantically and sexually, and punished when they refuse to be. If disbelieving a queer woman about her own feelings and cajoling her into a sexually violent heterosexual relationship isn’t a form of lesbophobic prejudice, I don’t know what it is — yet you rarely see it documented in survey studies like these.

It’s clear that the research literature Napier bases her work on has some theoretical gaps in it, because it doesn’t take a comprehensive look at all the forms homophobia can take. But, in seeking to understand why gay men might face more overt prejudice than queer women do (and why trans women might face greater social disapproval than trans men), Napier does acknowledge a few important social forces worth talking about (and which many trans feminists would themselves point to).

First, Napier name-checks something called the “Subordinate Male Target Hypothesis,” which posits that men from low-status groups are more harshly & violently subjugated than women from those same groups.

Generally speaking, this term does describe a real phenomenon. Men from “subordinate” groups are often made the overt “target” of prejudice— oppressive laws often single out marginalized men as violent, uncontrollable, predatory, and criminal, compared to marginalized women, who are more likely to be ignored and erased. And marginalized men do pay a heavy social price for being made into the target — typically experiencing physical assault, arrest, incarceration, and state repression at heightened rates.

For example, Black men are subjected to greater police violence than Black women, are (though both groups face much worse outcomes than white people do). And, as

points out, Arab men are more likely to be regarded as murderous and politically disposable than Arab women are (though both groups face immense colonial violence).What’s missing from the “Subordinate Male Target Hypothesis” is a clear explanation as to why prejudice hits marginalized men more explicitly than it hits women. Why is it that gay men are seen as more predatory than lesbians, Black men are viewed as more ‘dangerous’ than Black women, and so on?

I have previously theorized that marginalized men are treated as more dangerous because they possess a combination of marginalization and power that makes them a threat to the existing social order. The existence of marginalized men creates a contradiction: they’re seen as both lesser because of their race, sexuality, or class, and as formidable, because they’re men. And so, in order to prevent them from using what masculine power they do possess to resist their own oppression, gay men are targeted as gender-deviant degenerates, and Black men are dehumanized as “brutes” and “beasts” — hence the choice of Black male protestors at the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike to carry posters proudly asserting “I Am a Man.”

When men are oppressed, their oppressors aim to erase their manhood altogether — and with it, their humanity. Quite often, marginalized men try assert their humanity by reaffirming that they are, in fact, men.

This may be why queer men have grappled for so long with being seen as not sufficiently masculine. Everyone from “old guard” leather daddies to modern-day gay gym Chads have bent themselves over backward to prove they are strong and masculine — that is to say, still human, and therefore deserving of rights. When queer men don’t conform to traditional standards of masculinity, their oppression gets worse. They are viewed not as human men but as sissies, faggots, or fairies, and are brutalized and raped for their failure to emulate the straight, cisgender ideal.

And crucially, trans women are too.

Napier brings up societal bigotry against effeminate gay men as a reason to predict trans women will face more prejudice than trans men. Anything viewed as gender nonconformity in men, after all, is vigorously punished — and because of transphobia, trans women are seen by much of the world not as women, but as men who have failed at masculinity and must be corrected for it.

Trans men, in contrast, are often viewed as women who are aspiring toward manhood. They still get their gender invalidated, and they have to navigate misogyny, but their motives are at least understandable in a world where masculinity is superior. Like hyper-masculine gay men, trans men can sometimes receive a pass from some oppression for at least trying to become the societal ideal. But because they cannot ever match that ideal, both trans women and gay male “sissies” are the subject of dehumanization and disgust.

What Napier (and the Subordinate Male Target Hypothesis) miss is that trans women aren’t actually effeminate gay men. They’re women, and therefore also subjected to the full force of misogyny, which operates in ways both quiet and overt to keep trans women silenced, scrutinized, disempowered, and filled with self-doubt. Like many transgender men, they do encounter transphobia and misogyny on a daily basis, but they also experience transmisogyny, a structural, societal hatred of trans women that targets them specifically.

Transmisogyny was first named by

in her landmark 2007 book Whipping Girl, and you can find a variety of updated writings from her on the subject here. Transmisogyny has been written and theorized about for upwards of seventeen years at this point, mostly by trans feminist scholars, but as a social psychologist, Napier does not seem to be aware of it. And ultimately, though she considers several reasons that people in her sample might be more biased against trans women than against trans men, in her article Napier predicts that there will be no gender differences in how trans people experience bigotry.(Spoiler alert: She will be wrong about that. In this house, we believe all scientific claims should be falsifiable.)

In addition to being predicted by gender, homophobic attitudes also tend to be predicted by a person’s age, education level, religiosity, and political allegiances, so these variables are studied in Napier’s research too. And the data usually pans out in the ways you might expect: more conservative, more religious, and older people tend to be more prejudiced against both gays and lesbians, and more educated people tend to be more tolerant toward them. In her study, Napier predicts that these same variables would also be correlated with attitudes toward transgender men and women, in much the same way.

Napier’s study also aims to compare Western and non-Western societies on their attitudes toward trans people, and to examine whether a respondent’s country of origin affects the relationship between factors like religiosity and transphobia. It doesn’t make sense, after all, to compare a hard-core Evangelical Christian in rural Ohio to a devoted Shinto practitioner in Inari and call them equally “religious.” We cannot expect that their understanding of what religion even is to map onto one another cleanly, or for both religious practices to have an equal influence on how a person views transgender people.

As Napier further points out, the so-called “Western” countries of Germany, England, Italy, Spain, Sweden, France, Hungary, Belgium, and their former colonies (such as the United States, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, and Australia) have a variety of historical and cultural quirks that might make the outlooks of its people distinct, particularly as it relates to religion, conservatism, and social prejudices.

Napier writes:

“…As the medieval predecessor of the Roman Catholic Church, the Western Church promoted and enforced bans on marriages between close kin, which markedly impacted the culture… transforming societies based on extended kin networks into ones composed of loosely connected, neolocal, nuclear families (Henrich, 2021; Schulz et al., 2019).

Places influenced by the Eastern Church (i.e., the medieval predecessor to the Orthodox Christian Church), such as Eastern parts of Europe and Central Asia, and places not influenced by either medieval Christian Church (i.e., the rest of Asia and most of Africa), tended to maintain intensive kinship structures for much longer.

This divergence in societal structures is postulated to be the basis for the particular (“weird”) psychological tendencies found in historically Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) countries of Western Europe and places occupied by its cultural descendants (i.e., North and South America, Australia, and New Zealand).”

[emphasis mine]

In other words, though most psychological research has been conducted by Westerners who treat their culture as the neutral standard, what gets called the “West” has been shaped for centuries by church policies that artificially separated large families and pushed people into a more isolated existence.

This move away from close, rich kinship ties has left us Westerners with a uniquely individualistic, neoliberal point of view that we don’t share with people in most of the rest of the world, and it stands to reason that this might influence our outlook on faith, education, and all forms of non-conformity.

I have to really applaud Napier and other WEIRD theorists for writing about Western culture in this way. For a long time, social psychologists were predominately white Westerners who only ever categorized societies as “individualistic” or “collectivistic,” and viewed their own individualistic culture as the normative one. Labelling our culture instead as the WEIRD anomaly is exactly the kind of challenging reframe that the literature needed after many decades of such bias.

Unfortunately, the skepticism Napier brings to the practice of labelling cultures does not get applied to how she labels and understands gender — but I appreciate her and other WEIRD theorists’ willingness to push against decades of shoddy social science, regardless.

Let’s move on to the study’s methods, and then its results:

Napier’s data came from Ipsos, a global market research firm that sends monthly online surveys to large sample sizes in countries across the world.

In countries with widespread internet access, Ipsos’ samples are nationally representative, meaning that the respondents generally match their country’s overall demographic diversity. In countries with less robust internet access (such as Peru or Russia), respondents to Ipsos’ surveys tend to be more highly educated and wealthy and are more likely to dwell in cities than the national average, which absolutely impacts the results.

Every sampling method comes with significant pitfalls, especially when it comes to digital data collection, but using Ipsos beats recruiting college sophomores for extra credit, or paying random survey-takers on sites like Prolific or Amazon’s Mechanical Turk in terms of representativeness, at least in my view.

Between 500 to 1,000 study subjects were recruited from each of the 23 countries sampled in Napier’s study, for a total number of 16,756 participants. Each participant was asked to report their attitudes toward transgender women and transgender men on scale from 1 to 9, with 1 representing “extremely positive” feelings, and 9 representing “extremely negative” feelings. Attitudes toward gay men and lesbians were also recorded, to echo the Bettinsoli et al 2020 paper that Napier’s work builds upon.

It bears mentioning that Napier recorded attitudes toward transgender people in what some might critique as a transphobic way. Rather than directly asking participants how they felt about “trans women” or “trans men,” she asked participants’ their views on “someone was considered male at birth who feels they are actually female and so dresses and lives as a woman,” and “someone who was considered female at birth who feels they are actually male and so dresses and lives as a man,” respectively.

Napier argues that she must introduce transgender people in this way out of necessity, to prevent confusion among participants who might not be familiar with trans terminology, particularly in countries where LGBTQ rights are less widely discussed than the United States.

I can buy Napier’s argument that clarity is necessarily, as people routinely get confused about what trans men and trans women are even in the United States (my Grindr and Chaturbate messages can sure attest to that!). Still, I take issue with her choice to frame trans women as “males” and trans men as “females,” though she was careful to quality that both groups were merely “considered” to be such at birth.

No matter her good intentions, Napier’s framing here primes respondents to think of trans people as their assigned sex at birth. We can imagine that this might incline her sample to express more bigoted viewpoints than if they were shown a picture of a trans woman and told a few details about her life and then asked their feelings about her, for example.

In social psychology, prejudice is said to operate on three different levels: emotion, thinking, and behavior, and these three elements may not always line up with one another. A racist white person might try to behave in a cordial, friendly manner toward Black individuals, for example, while viewing them as inferior; or a person might claim to harbor no ill will toward bisexuals while acting visibly uncomfortable around them.

Furthermore, a person’s beliefs about groups in the abstract may not line up with how they regard individual members of those groups in the particular. If you’re a queer person with conservative relatives, you probably know this intimately. A person who repeatedly votes against transgender rights may profess to love you and support you in your every endeavor, including in your transition.

Because of complexities like this, there is no one true way to measure bias. The questions we ask shape the results that we find and the forms of truth that we get access to. As my undergraduate research advisor Wil Cunningham once told me, every study’s results are true — for that sample, using that measure, at that point in time.

In addition to reporting their feelings toward trans and gay people, Napier’s survey respondents were also asked whether they believed it was possible for a person to be a gender other than the one assigned to them at birth (Napier calls this a “gender identity denial" measure), and to report their religiosity, conservatism, age, and education level. Region of course was also a crucial variable in the study, and so analyses are performed both on the level of individual country, and pooled in order to draw comparisons between Western- and non-Western people.

Methodologically this is a pretty tight, simple study — just a handful of measured variables and the relationships between them are examined. The analyses are also relatively easy to follow, even if you’re not a statistician. I’ll do my best to summarize the findings and describe what they mean as simply as I can without glossing over anything of import.

We’ll begin by taking a look at what effect a trans person’s gender identity has on the public prejudice against them:

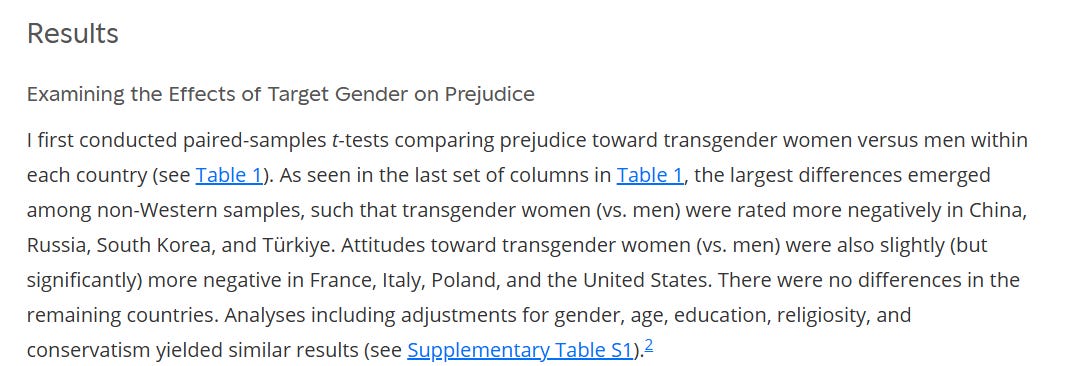

In the most simple form of her analyses, Napier finds that people report greater dislike for trans women (compared to trans men) in China, Russia, South Korea, Turkey, France, Italy, Poland, and the United States. The size of this effect is more pronounced in the non-Western countries listed than the Western ones. This runs counter to Napier’s prediction that people would be biased against trans men and trans women equally.

The gender of the survey respondents also mattered — with men on average reporting far more anti-trans bias toward both trans women and men, compared to women respondents.

Furthermore, Napier found that age, education, conservatism, and religiosity also were associated with overall anti-trans bias (more on these effects later). Accordingly, Napier built a multilevel model that predicted transphobic attitudes using the gender of the “target group” (trans women versus men) as a predictor, as well as respondent’s gender and region, and utilizing the other variables (age, education, conservatism, and religiosity) as controls.

Here’s what she found:

The first important finding to flag here is that, when collapsed across all countries sampled, participants were consistently more biased against trans women than they were trans men.

When isolating survey respondents by region, however, Napier found that non-Westerners reported a greater bias against trans women. Participants in Western nations still appear to have greater dislike for trans women than trans men, on average, but when isolated by region, the pattern did not reach the level of statistical significance. As in her previous analyses, Napier found that the men in her sample were more biased against trans individuals overall, compared to women, and that non-Western men were particularly prejudiced.

Next, Napier turned her focus to the measure of “gender identity denial” — which asked participants where it is possible for a person to be a gender other than the one they were considered at birth.

Participants from Russia, China, India, Peru, Hungary, South Africa, Poland, and the United States disagreed the most strongly with the idea that a person’s gender can change, of all the 23 countries sampled. Spain, a nation that offers hormone replacement therapy on an informed consent basis, ranked as far and away the least transphobic region in the sample, with respondents generally considering it possible for a person to change their gender identity from what they were considered at birth.

After this, Napier combined attitudes toward both trans women and trans men to compute an overall measure of transphobic attitudes, and built a model examining the effects of all variables in the study, as well as how those variables interacted with one another. Once again, she discovered that men feel more negatively toward trans people than women do, and that non-Western men, in particular, expressed greater transphobia.

Napier also discovered that more highly educated people were generally less transphobic, regardless of region. Older people, on average, were more biased against trans people, and this effect was heightened in non-Western countries. Conservatism was associated with more transphobic bias, particularly in Western countries such as the United States. In Western countries, higher religiosity predicted greater transphobia, though it did not in non-Western countries.

So far, these results mostly line up with Napier’s predictions, and most of the existing social psychological literature on the subject. Nothing super surprising here. Where things get a little more complicated, though, is in step two of the analyses, where Napier entered attitudes toward gay men and lesbians as a control.

After controlling for attitudes toward gay people, younger people were actually found to be more transphobic than elders in the Western countries in the sample. What this means, in essence, is that for older people in countries like the United States, attitudes toward gay people and trans people pretty much hang together: either you accept all LGBTQ individuals, or you don’t.

But among the younger generations, homophobia and transphobia are somewhat more independent. Perhaps on account of rising transphobic rhetoric, a sizeable number of young people in Western countries support gays but strongly dislike trans people. The LGB without the T movement sadly seems to have found some converts among the newer generations.

When controlling for attitudes towards gays and lesbians, the effect of education and conservatism on transphobia largely dropped away. This suggests that more educated people are more tolerant towards both gays and trans folks (which is not super surprising), and that conservatives are less tolerant toward both (also a pretty predictable result).

The effects of religion however, flipped: when controlling for anti-gay bias, highly religious people were actually less biased against trans folks than the non-religious were.

This suggests there’s a contingent of highly religious people who are more tolerant toward trans people than they are gay people. This may indicate they believe that transness, which is a matter of identity or personal feeling, is not a choice or not sinful, whereas being gay is. Since some religious doctrines preach specifically about the evils of gay sex, it’s possible some highly religious individuals view transness more neutrally. But truthfully, more study would be needed to tease this effect apart.

Finally, Napier examined the relationship between “gender identity denial” and general transphobia. She found that people who do not believe it’s possible to change one’s gender are in fact more transphobic (no surprise there), and that a person’s beliefs about the changeability of gender had an influence on transphobia that was statistically independent of homophobia.

In other words, transphobia isn’t just the result of homophobic people applying their bigotry to all members of the LGBTQ umbrella equally — rather, transphobia reflects, in some part, a person’s ideology about what gender is and whether it is changeable.

This might not sound like it’s a big deal, but it suggests that the rhetoric of TERFs, “gender critical activists,” and far-right transphobes about the immutability of gender might have had an influence on public attitudes over the years. People who hate trans folks aren’t just doing it because they hate all queers — they’ve developed specifically transphobic beliefs about how the world operates. Transphobes are therefore not merely “ignorant” about what trans people are — they know about us, and they have constructed a worldview that deliberately shuts us out and makes them more biased against us.

Napier’s study is impactful for a variety of reasons — though from how she discusses and makes sense of her findings, it doesn’t seem she realizes yet just how much.

The most obvious major boon of the study is both its novelty and size — it is truly one of the very first studies to contrast attitudes toward trans women with attitudes toward trans men ever, and it utilizes the largest and most internationally diverse sample on the subject to date.

In her study, Napier presents some of the first (and arguably best) research empirically suggesting that prejudice against trans women is elevated compared to prejudice against trans men. Furthermore, Napier identifies that prejudice against all trans people is consistently greater among men, which aligns with prior research showing that even when queer women are at an elevated rates of domestic violence, it’s still men who are predominately responsible for their abuse.

In the discussion of her findings, Napier posits that people might be more prejudiced against trans women for a couple of reasons. One of the first causes she presents is the growing politicization of trans identity — with trans women most commonly being made the focus of hateful rhetoric.

She writes:

“…one reason why there might be more bias toward transgender women (vs. men) in some Western countries, like the United States, could be at least partly due to political campaigns that have promoted anti-transgender legislation by portraying transgender women as a threat to vulnerable groups, like women and children (Atwood et al., 2024). This rhetoric has not just come from the political right but also from some feminists (Worthen, 2022).”

It’s true that trans women are made the focus on transphobic policy proposals by reactionary conservatives and so-called “gender critical feminists” alike.

When bans on trans and gender-nonconforming athletes in competitive sports get proposed by such groups, it’s virtually always the specter of trans women competing among cis women that supposedly haunts their conscience. A recent fear-mongering campaign advertisement for Donald Trump emphasized that Kamala Harris supported the inclusion of “biological men” in “girl’s” sports. When conducting public opinion research on the subject, pollsters will typically ask about a respondent’s attitude toward trans girls competing in K-12 athletic programs, and sometimes fail to mention the existence of trans boys altogether.

The relative “invisibility” of trans masculine people in such discussions does benefit us: Multiple transgender men and AFAB nonbinary people participated in this summer’s Olympics. Zero trans women were permitted to participate at all.

Placing restrictions on public bathroom access has been another major political priority for transphobic activists in the United States, where at least 13 states currently have some kind of trans bathroom ban in place. In political advertisements advocating for such statutes, it is always trans women who are presented as a looming threat who must be kept out of such spaces — never trans men.

“Any man at any time could enter a woman’s bathroom simply by claiming to be a woman that day,” says the narrator of one conservative ad opposing Houston’s proposed equal rights ordinance. “No one is exempt. Even registered sex offenders could follow women or young girls into the bathroom…”

The prospect of a transgender man sidling up to the urinal to pee beside a cis man is conspicuously absent — unnamed, untargeted, and not feared.

Napier has obviously observed this trend of scapegoating trans women. But she lacks a deeper context for why trans women are made the target of so much of transphobic rhetoric and legislation — that the hatred of trans women she sees in her study and the focused political attacks on them share a common cause.

That cause, of course, is transmisogyny, the structural oppression of trans women.

Ever since Julia Serano first described transmisogyny as a distinct form of prejudice in the aughts, trans feminist scholars and community members have been documenting the unique biases they face due to their trans feminine identities.

But their accounts are frequently ignored — by cisgender feminists, who exclude trans women either partially or completely from their gender liberatory movements by claiming that trans women benefit from “male socialization” and do not experience the fullness of gendered oppression, and by trans men and nonbinary people, who often diminish trans women’s concerns by asserting that since we brush up against both transphobia and misogyny, our experience is not fundamentally different from theirs (or if it is different, then we are suffering from transmisandry, which is totally real and actually worse).

So what is transmisogyny really, and what makes it distinct from either sexism or transphobia? If you’ve been following along so far, you should have some understanding of its contours.

Trans women are positioned in society as lower-status, because they are women, but because they are also trans, they are frequently also reviled for a perceived proximity to “maleness” that supposedly makes them more powerful and dangerous than either cisgender women or trans masculine people.

Yet for all their supposed “maleness,” trans women have repeatedly failed throughout their lives to conform to the masculine standards that were forced on them since birth. And as we’ve already discussed, a failure to sufficiently perform maleness is typically grounds for a person to be regarded as basically inhuman.

Trans women, then, are viewed as both women and not-women, failures at masculinity and threatening males, hyper-visible horrors and hypersexualized objects that won’t stay in their place. They are at every turn targeted, objectified, unpersoned, and attacked.

And even in the depths of their oppression, trans women get told that they are not really suffering — that they’re privileged, that they lack a woman’s essential physical qualities, that all the public discourse about their bodies is somehow to their benefit, because it makes them “visible,” and that whatever experiences of abuse they do try to document are too confusing and esoteric for anybody else to care about.

In her second book, Excluded: Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive, Julia Serano provides an especially telling example of transmisogyny in action— and it comes from Napier’s and my home field, psychology. While attending a conference for Women in Psychology, Serano observed how one panelist, a therapist, described both her trans masculine and trans feminine patients:

“First, the therapist discussed the trans masculine spectrum person, whose gender presentation she described simply as being “very butch.” She discussed this individual’s transgender expressions and issues in a respectful and serious manner, and the audience listened attentively.

However, when she turned her attention to the trans feminine client, she went into a very graphic and animated description of the trans person’s appearance, detailing how the trans woman’s hair was styled, the type of outfit and shoes she was wearing, the way her makeup was done, and so on. This description elicited a significant amount of giggling from the audience, which I found to be particularly disturbing given the fact that this was an explicitly feminist conference.”

When a person who was assigned female at birth presents in a masculine fashion, it is seen as serious, and respectable, and there is room for the fullness of their humanity to be considered. But when a person who was assigned male at birth presents in a feminine fashion, a ton of sexist scrutiny gets applied her appearance, alongside outright mockery. She does not get to be a complex human with a variety of therapeutic needs. She’s an object of study and criticism, even to other women and trans people.

This is not just sexism, and not just transphobia either, but a particularly potent and vicious intersection of the two that does not get lobbed at either cis women or trans men.

That such remarks came out of a psychology conference gives Napier’s complete unawareness of transmisogyny a deeper context. The fact that a widely published scholar like Napier, who studies gender bias and queerphobic attitudes, has never even heard of transmisogyny, doesn’t know to cite Serano, and didn’t know to expect it in her study is itself evidence of just how deep the bias against trans women goes.

As a social scientist, I’ve noticed just how under-represented trans women are in gender studies departments, feminist psychology labs, and on conference panels about queer issues. In fact, in the nearly twenty years that I have been occupying social psychology labs, I have yet to encounter even one trans female social psychologist. There are trans women therapists, to be sure, and I’ve met many of them, but trans women are pretty pervasively excluded from conducting research in psychology, and their theoretical work is rarely consumed by anyone who is not themselves a trans woman.

This exclusion goes far beyond social psychology, of course. As a trans masculine person, I’ve repeatedly been asked to contribute to articles on trans reproductive health where no trans women were even interviewed, and to participate in seminars on transgender rights where not one trans feminine person was present. I have seen trans masculine people head academic departments and boards of nonprofits, watched us get big book deals with large advances, and seen my own work placed on lists of “books by women and trans authors” where not one single piece of writing from trans women was included.

I am disturbed by such things, and I’ve spoken up to demand that trans women’s voices get centered whenever I’ve had the opportunity. But the inclusion of a group of highly marginalized women shouldn’t hinge on the support of a man. It is perverse that trans women are not believed when they have documented their oppression so thoroughly, for so many years, and that their carefully crafted theoretical work remains so pervasively ignored.

All of this is why Napier’s research has the potential to be so impactful. It’s a massive empirical study, conducted by a cis woman in a field that rarely acknowledges trans women, that nonetheless points to the fact transmisogyny exists. It’s a piece of carefully collected evidence that trans women and their allies can point to as proof that bias against trans femmes really is a societal problem, even an international problem, without being accused of overly complicating things, “erasing trans men’s struggles,” or dealing in anecdotes.

Trans women shouldn’t require external validation from cis women and trans men in order for their oppression to be believed in. But I do hope that this study does move both cis women and transmisogyny-exempt trans people to consider that we are not the center of feminism, and that an entire other population of frequently brutalized and silenced women exists, and has been trying to reach out to us for understanding for a very long time.

Anecdotal but I can testify to the "highly religious people are more likely to be anti-gay but neutral on trans issues" thing. Growing up in the 90s in a conservative, Protestant Christian, religious bubble, homosexuality was repeatedly warned against, with reference to Bible passages that are explicit in their wording (depending on translation, anyway).

But there aren't any anti-trans verses, really. The closest is a prohibition on cross-dressing, or vague statements about feminine men. The result was that I found people would be vocally anti-gay, but either have no opinion or even a positive one about trans people.

However, that's changed with increasing trans visibility and acceptance. As I reached adulthood and through to today, anti-trans rhetoric has far increased as people in positions of authority find increasingly tortured scriptural arguments against us and our existence, often directly in conjunction with Creationist beliefs (specifically, a pervasive idea that God assigns us our unchanging gender, and to deny this is to deny His Sovereignty).

Grateful for your interpretation of this study, Dr. Price. Within the last few months, my adult child has faced multiple instances of transmisogyny. During the earlier stages of transitioning, when Evvie was identifying as nonbinary and could still “pass” as male in the work environment, things were challenging but manageable. Now that medical/physical changes are clearly defined transfemme, pronouns are shifting from they/them to she/her, our adult child has been blatantly rejected in multiple situations. Worst of all, losing employment and having no luck getting work at even the most basic desk job. Evvie has an engineering degree from Notre Dame University, certification in coding, has worked successfully in the tech field full time for over 7 years. There’s no lack of skill, ability, willingness to work hard, or intelligence that should prevent being hired. It’s how she presents. 100%. I’m not sure how I feel about cutesy names like mama bear that my young people throw around, but the anger about how much discrimination and mistreatment has affected my child is real. The world can be a cruel, hateful place for anyone perceived as different and trans women seem to be particularly vulnerable. The anti-trans sentiment of the newly-elected leadership of this country terrifies me. Thank you for continuing to write and share your work to combat this disease of hate we have as a society. It’s good to know we aren’t alone. 💛

[If anyone reading this has a connection to employers in the Chicago area or remote who are in need of a genuinely good person to join their team, let me know!]